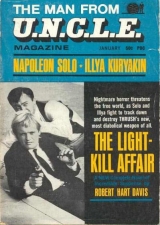

Текст книги "[Magazine 1967-01] - The Light-Kill Affair"

Автор книги: Robert Hart Davis

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 5 страниц)

It seemed less a nightmare.

Nesbitt's voice cut across Solo's thoughts. "Death. Yes, death works. Death is useful here, too, Solo. Professor Connor's death was useful—"

"You told us you didn't know about his death," Solo raged.

Dr. Nesbitt shrugged as if reminding him that nothing could matter less than what he said to them, or to anyone from the world of his past.

"He was sentenced to death by our highest court," Nesbitt said. "There was nothing I could do except see that he was executed in the way that would be most useful to us. Yes, even death must be useful."

Solo shook his head, hearing the doctor's words, but unable to believe a man could have so far receded from any human feelings of remorse, guilt, love or regret.

Dr. Nesbitt regretted nothing except time lost from his experiments.

"I'm sure our deaths will serve you in some useful purpose," Solo said bitterly.

"When the time comes. Meantime, you and Mr. Kuryakin will work for us as mindless slaves—made mindless by light, Mr. Solo. And as for Miss Connors, I can use her body in my experiments with my plants—"

"Dr. Nesbitt. Ivey!" Bikini cried out, tormented. "What's happened to you? Once you loved my father and me."

"It's no good, Bikini," Scio said. "He's gone crackers—"

"You think I'm insane, Solo?" Dr. Nesbitt raged.

Solo shrugged. "I suspected it all along. I'm convinced, now that you've decided to use a body like hers as plant food—"

"Mr. Solo, I assure you that only the plants are important here. They are mutations, grown from the most ordinary jungle carnivorous species, from those pitcher plants devouring flies and insects to what you saw in that hothouse—"

"Oh, Ivey," Bikini wailed. "Once you were the most beloved man in—"

"A fool girl like that, what does she know?" Dr. Nesbitt said to Solo, still refusing to speak directly to the daughter of his old associate. "Does she know of the horror of being stared at like a freak because of my disfigured face?"

"That's not true!" Bikini cried. "Nobody ever—"

"What does she know of the way I lived, dreading the way people cringed at the sight of my face? They wouldn't even let me work in peace until I came here.

"My plants don't cringe from me. My mindless slaves neither see nor react to my face. I don't have to watch people turn away."

"You're buried here," Solo said. "Worse than buried."

"That's where you're so wrong. Solo. Perhaps I shall yet control the world." Nesbitt looked around him now as though he wished to talk more fully about himself and his work.

"I shall set the world free by the use of light, Mr. Solo. I'm sure you've heard the theory that all light rays enter the eyes of animals and people, directly influencing the pituitary gland.

"In the same general way light radically affects the growth of plants. Scientists have exposed young rats to the rays of television rays and they die of severe brain damage within twelve days. By my own application of this theory I have made my slaves mindless.

"And I use the same X-ray light that comes from TV tubes, many times intensified. My jungle plants exposed to this X-ray light grow at phenomenal speed and to unheard of sizes.

"Light, Mr. Solo. Light to control. Light to kill. Light to grow. Everything subject to the intensity of my X-ray light. From a glow soft enough to be harmless to strength to register wildly on a Geiger counter. With light I shall control the world."

"Sure. And THRUSH lets you believe that you will. In exchange for what? For those plants which will grow and multiply and kill?"

Nesbitt smiled. "That is part of my experiment."

He shook his head and lowered his voice to that reasonable tone so characteristic of the deranged, "So you can see why I cannot permit you people to leave here—to spread the word of my work?"

THREE

ILLYA FELT himself being lifted up from the corridor floor where he'd crumpled like a bug when stunned by the light beam.

The men lifting him carried him loosely between them. They did not speak to each other, moving like robots.

Double doors swung open in the corridor walls ahead of them and Illya saw he was being carried into a room of dark chocolate walls with hundreds of small lights set under the ceiling, across it, and along the sills.

The guards placed him in an ordinary appearing chair which lighted up under his weight.

When he attempted to stand, Illya found he was helpless to move. The action of the light was like a terrible magnet holding him pinned to the chair.

There was no pain of any kind. It was simply impossible to break the pull of the light-magnets which secured him in the strange chair.

After a moment Kuryakin stopped fighting. He felt the strength return to his arms and legs. He still had a sense of being dizzy, but even this lessened after a few moments. He examined the chair as the guards backed out of the room.

The doors closed and locked, Illya supposed. He looked around, finding the room extremely dark and himself seated in the lighted chair like an illumined island.

He shifted his weight, attempted to raise his arms from the chair.

He could not move. The darkness seemed to press in upon him, and he had the eerie sense that unseen eyes probed at him from the walls.

Illya felt a desperate urge to cry out, but he did not. He wouldn't give hidden onlookers the satisfaction.

Suddenly he heard the crackling noise such as a TV tube made warming up, and a forty inch screen suddenly lightened the dark wall directly before him.

Dr. Nesbitt's scarred face appeared upon the screen. His mouth pulled into a mocking smile. He said, "Are you comfortable, Mr. Kuryakin?"

Illya did not answer.

"Quite secure, Mr. Kuryakin? By now, I'm sure you're convinced you cannot get out of that chair until I want you out of it. Eh?"

Illya waited. He hated this weird darkness. The television screen flickered, the gray shadows leaping across him, Dr. Nesbitt's strange eyes fixed upon him.

"The tests I'm about to subject you to, Mr. Kuryakin," Dr. Nesbitt said from the screen in his best lecture tone, "will be most fascinating to you, I'm sure, as long as you retain your senses."

The screen remained lighted, but Dr. Ivey Nesbitt's broken face disappeared.

"You look better like that," Illya said to the blank screen.

Illya heard the dim hum as some small motor was activated. The strip of flooring upon which his lighted chair was secured moved suddenly, sliding backward about ten feet.

The screen gradually darkened and the multicolored lights flashed on, along the ceiling and the floor. Somehow the room remained dark despite the many lights, and then Illya supposed this was caused by the action of one set of colored lights upon another.

His eyes burned slightly so that he wanted to rub them, but he could not lift his hand to his face.

The small motor hummed again and the strips before and behind the chair slowly folded over him and locked, making a wide circle.

After a moment the motor engaged again and two sections of the flooring on each side of him locked into place, securing him and the lighted chair inside a dark drum.

The lights on the chair flared and died, leaving him in darkness. The magnetic power was cut off, but now there was nowhere to go. There was not even room enough to stand up inside the drum.

Nesbitt's voice pursued him, even here. "Pain from light, Mr. Kuryakin. Are you acquainted with the phenomenon? I assure you, you will be well versed in the subject soon. The simplest application I can give to prepare you for what's going to happen to you is that of the young children, sitting for hours two to three feet from a television set. They suffer all manner of illnesses, including emotional disturbances, all induced by the X-ray light from that tube. The larger the picture tube, the greater the voltage.

"In other words, the greater intensification of that X-ray light, the more pain induced. We use this principle, Mr. Kuryakin, but of course, for our purposes, we have greatly refined it, and find that colored lights offer a great deal more intensity, just as does a colored tv picture tube."

The voice snapped off and for a moment the silence and darkness persisted until Illya thought Nesbitt had gone away and forgotten him.

Somewhere a switch clicked, small motors hummed, and the first banks of lights flooded the drum. For a long time they remained constant, and then they alternated, colors flashing around and around the drum, faster and faster.

Illya Kuryakin sweated. For a long time he was conscious of no other reaction to the lights.

They grew brighter, the colors alternating in some crazy scheme. The effect was of a clockwise flashing of lights, until suddenly Illya felt himself and the chair following, the drum turning with the lights, but at first slowly. Illya felt slightly nauseated.

He closed his eyes tightly. He could still see the lights, still felt the drum spinning him over backwards. He pressed his hands over his eyes, and realized the chair was stationary, the drum was not moving, only the whirling lights caused the sickening sensation of spinning.

He pressed his arm over his eyes. Sweat burned into them. He cried out involuntarily.

Although he pressed his arm tightly across his eyes, he suddenly could see the flashing lights through them!

The strength of those lights had been intensified. He could not escape them. After a moment the chair seemed to tilt backwards, to tip, fall and then turn, following those flashing lights.

Illya Kuryakin gagged, sick at his stomach.

The lights whirled faster and faster. He screamed as he wheeled and skidded, spinning around and around in the immobile chair, the unmoving drum…

The lights flashed off. At least Illya Kuryakin thought they did. The sides of the drum lowered; the top pieces unlocked and folded down.

Though he was sick at his stomach, Illya's mind was clear enough to warn him to get out of that chair.

He lunged upward.

He was not quick enough. The lights flashed on, the magnetic power of the chair held him securely. The chair slid forward.

For a long time he could feel the lights still spinning inside his head. Buckets of hot water were thrown on him, followed by buckets of cold water.

A voice from somewhere told him to rest. He did not recognize the voice. There was an almost kindly timbre in it, and he thought wildly that the speaker might have human emotions, if only he could appeal to him.

But then the voice died away and he was left locked in the chair, a bright white island in the chocolate darkness.

Illya Kuryakin didn't know how long it was before he was returned to the light drum—perhaps hours, or days, or only minutes. His head ached and time had already lost meaning.

He closed his eyes against the whirling lights, but this did not help. The bright colors penetrated first his eyelids, then seemed to enter at his temples, throbbing behind his eyeballs, twanging at the taut nerves. He pressed his fists hard against his temples and then the steady beams of colored lights battered at his forehead, at the base of his skull, the crown of his head.

Illya's head ached excruciatingly now. Even when he came out of the drum, was doused with water, fed something which would not stay on his stomach, and told to rest, the headache persisted.

The human body might become accustomed to anything, even the throb of a headache if it remained constant. But the pressures, the intensity of the light was increased, lessened, speeded up.

And he spun in the drum, screaming against it, until he could not even hear his own screaming.

He could feel his nerves going.

He wanted to break down into tears, to cry over nothing.

The lights never stopped whirling for him now, even when he knew they were off and he was outside the drum. They whirled, jabbing like lances through his brain.

The kindly voice asked him what day it was, and Illya could not answer. And after a long time the gentle questioner inquired Illya's name, and Illya could not answer.

He no longer knew.

For a few brief moments when he was doused with the buckets of ice water, Illya had lucid thoughts. He knew his name. He knew why he had come to this place. He remembered the lights. He remembered the kindly voice, the way he strained, listening for it, how lost he was when it went away and left him in the darkness.

Then the hot water would strike him and the lights would whirl.

In his lucid moments he warned himself his mind was going, his nerves already frayed, his emotions damaged. He had to cling to some thought that had nothing to do with this place. As the cold water struck him, he remembered New York, the restaurants, the Village, the subways, the sun on the United Nations complex early in the morning.

He gritted his teeth, swearing to hold these thoughts, to shut out what was happening to him.

The hot water washed it away.

He'd long since lost count of how many times he had been placed inside the drum. He never escaped the lights except for the briefest moments. The ice water no longer felt cold. Now there was no difference between hot and cold.

He'd trap a thought of some distant place, but the first whirling of the lights fragmented the thoughts; he was unable to hold on to them.

The light intensified, and so did the pain.

As the drum parted and the chair slid forward his wrist watch scratched his cheek.

Frantically, he grabbed the watch band, jerked the watch from his wrist.

The motor hummed, the short slide was almost over, the immobilizing lights would flash on. Or maybe they no longer bothered to magnetize him to the chair. Illya didn't know.

His mind could contain only the thought of the watch. He smashed it in his palm on the arm of the chair.

Trembling, he shook the broken shards of glass into his mouth, and dropped the watch.

At this instant the water struck him. He chewed sharp pieces of glass, feeling it cut his gums, his tongue, the roof of his mouth. He chewed again. Blood oozed from his lips.

Kuryakin could feel the temperature of the water. It was cold.

FOUR

SOLO PROWLED the small room which adjoined one of the thickly grown hothouses.

Bikini slumped against one of the three solid walls. She cried for a long time, her dark head pressed into her arms.

Solo stood at the fourth wall. It was thick green glass and afforded a view of the lushly growing cannibal plants out there.

He shook his head. He had no way to break this glass, yet it was almost as if Nesbitt wished he would. It was as though they dared him and Bikini to attempt to escape across that tangled growth.

He drew his arm across his forehead, wiping away perspiration. The cell was as hot as the hothouse beyond the glass, and more breathless.

The door was thrust open and Solo looked in that direction.

A guard stood at the opened door with a light-gun in his arms. Another entered the small hot room. He walked slowly, like a spring-wound toy that has run down.

His face was set, his eyes vacant. He faltered slightly.

Solo caught his breath. The man's face was battered, his hands cut. This was the man who had fought him at the canyon ledge, the one he'd left dangling over the precipice. He had hit him in the face with his shoe until the pain somehow got through to his consciousness.

The guard looked at Napoleon Solo, shook his head in an almost imperceptible movement, then he turned and walked, still faltering, toward Bikini.

Solo set himself to jump the guard if he harmed Bikini. He closed the armed sentry at the door from his mind. It might be the last thing he ever did for Bikini.

But the guard merely drew a folded sheet of paper from his tunic.

He held it out toward Bikini in a quivering hand.

Solo caught his breath. He recognized the form, it was a 'a summons to death' like the one delivered to Bikini's father at the hotel in Big Belt.

Bikini took it. She didn't even glance at it. She recognized it, too.

The guard turned and stalked toward the door.

Bikini jumped up. She ran to Solo and pressed herself against him, tears in her eyes. Solo closed his arms about her, comforting the miserable, frightened girl.

The guard was barely at the door when Joe, Nesbitt's Indian assistant, brushed past the door sentry.

He caught the guard by the shirt front and pushed him against the wall, as if forgetting Solo and Bikini in a sudden savage fury.

Joe switched on a wall light, marched the guard to it, forced him to stare into its brilliance. The man gazed at the bulb, unblinking. His dry eyes did not even water.

Joe spoke urgently but quietly to the man with the light fixed in his eyes. The Indian's voice was low, controlled, almost kindly. "The summons was for Napoleon Solo. The summons was for Napoleon Solo."

Solo watched Joe, fascinated. He forgot the misdelivered summons. This didn't seem very important right now. He was seeing one of Nesbitt's mindless slaves being programmed, by light. The programming was much like that done to computers, Solo thought, except that the computers' were memory tapes and transistors, and here the scientist was dealing with a man driven mindless by some sort of exquisite torture.

FIVE

THE INDIAN assistant moved toward Napoleon Solo. The man's dark face was impassive.

"We've come for the girl," Joe said.

Solo flinched, looking down at Bikini's dark head pressed on his shoulder. She was deeply asleep. She had been able to relax because she trusted him. She felt secure in his arms, even in this place.

"She's asleep," Solo said, his chilled voice warning Joe flatly to keep his hands off of her. The Indian merely smiled coldly, spoke sharply, and the two guards entered, armed with small rifles. They stood ready at Joe's side.

"You'll still have to take her," Solo said.

The Indian bent forward, catching Bikini's arm. He shook her. The girl came awake slowly, protesting.

Solo set himself. Joe shook Bikini again, lifted her. As Joe rose, Solo came up on the balls of his feet. His fist caught Joe on the jaw, staggering him.

He released his hold on Bikini and fell backwards. He struck hard against the glass wall. It trembled under his weight.

Beyond the glass the huge leaves and thick limbs quivered, set into motion by the vibration.

Solo came up, moving, crouched toward Joe.

A rifle butt caught Solo in the forehead. Bikini screamed,

Solo staggered, his legs buckling under him. He landed on his knees. Vaguely, he saw Joe pull himself up, shake his head and then order the guards out of the cell with the girl.

Solo saw it as if from a great distance, and he knew Bikini was screaming, but he could barely hear her.

The guards half-dragged Bikini to the corridor entrance of Hothouse One. Behind them, Joe tested his jaw, his face twisted.

The guards thrust open the doors. The giant plants inside set up a rustling, waving motion at the movement.

"Inside," Joe ordered.

Bikini shook her head, staring wide-eyed at the long writhing green tentacles, the huge crying leaves.

Joe jerked his head. The guards caught Bikini's arms, thrusting her through the door.

Bikini toppled on the walkway. She sprang to her feet and ran to the doors. They were closed in her face. She beat against them.

The sound set up a wild reaction among the plants. The snake-like limbs reached out, the leaves waved, the thick trunks seemed to quiver.

Bikini pressed against the door, staring in awe at the giant green plants.

From an intercom Dr. Nesbitt's voice seemed to fill the room, setting the plants in violent motion again.

"You must fight to live, my dear. You don't have a chance. As you see, some of the walks are wide. Some are almost grown over. But the wide ones are open only be cause the plants are pulled back. Any movement in them and the plants will crowd in, reaching out, even growing in the direction of the sound. It's the way they live, my dear."

Bikini pressed her fist over her mouth to keep from crying out.

"Perhaps if you run, my dear," Nesbitt's voice suggested. "Run. You may find a place to run. You may break free from their tentacles. You must offer some challenge to the plants, my dear, or your unfortunate death will serve no useful purpose."

Suddenly Bikini screamed.

As Nesbitt had talked, long green tentacles had struck against the walls, holding as if with suction cups, and now reached out swiftly toward her.

They approached from both sides of the door.

"You're not safe there, my dear," Nesbitt's voice taunted. "I suggest you run."

Bikini did not move. Petrified with fear, she remained pressed against the door until the slimy, serpent-like tentacles clapped against her arms from both sides.

Screaming, she broke free and ran again.

Ahead of her the center aisle seemed wide and clear. But as she ran along it, the motion of her body stirred the plants on each side into frantic action. Trunks bent, leaves shook and tentacle limbs grasped out.

A huge arm-like limb struck her across the head and sent her reeling.

Toppling to the floor, Bikini slid along it. She remained there stunned for only a few moments, but smaller limbs, nearer the ground, sprang out, clutching at her legs, arms, dress.

"Run. Run. Run." Nesbitt's voice commanded loudly from the intercom speakers.

Bikini leaped. She realized in sudden horror that Nesbitt was like a cat playing with a mouse. When he shouted at her to run, it wasn't advice he was interested in. His voice, any sound, caused violent reactions in the plants so that they swung out, reaching toward the sound. And when she moved, this activated them even more violently.

She ran a few steps. Tentacles struck out like snakes. One closed about her throat. She caught at it, tearing it free.

Her movement brought newer limbs grabbing at her. In horror Bikini screamed, and more bushes leaned toward her, closing in upon her.

She broke free, falling away from the writhing tentacles.

She stumbled and fell to the floor on a narrow walk. The plants near her trembled, sending out eager feelers.

Holding her breath, she inched forward, and the bushes quieted behind her.

The exhausted girl laughed, on the verge of hysteria. Plants reacted, snagging at her. She lay still for some moments. The plants quieted.

When Nesbitt spoke over the intercom, they roused again, but seemed to subside.

She told herself she must lie unmoving where she was. These plants reacted to noise, lay quiescent in silence.

She lay still. For some moment nothing happened. From the intercom, Nesbitt spoke, his voice loud, taunting.

The plants quivered, rustling, unfurling long green limbs.

Bikini remained unmoving. She drew only shallow breaths. Perspiration stood on her forehead, burned into her eyes, but she did not stir, even to wipe it away.

She wanted to laugh in exhausted triumph. But she made no sound. The plants around her seemed quieted. They barely stirred, even when Nesbitt's voice rattled the intercom.

She did not know how long she could remain in this position., but she was alive, and this was all Bikini was thinking about.

Suddenly she screamed, the sound spewing from her.

She lunged upward to find green branches closed on her ankles and her legs, like ropes.

Bikini fought wildly at the limbs, breaking free. But her movement set the nearest plants in wild motion.

She leaped to her feet, trembling, and stared quickly around, her face rigid.

Then she ran, fighting the limbs around her.

Dr. Nesbitt's voice taunted her. "That's better, my dear. That's the kind of challenge that's worth while. Run, girl, run!"

ACT IV—INCIDENT OF THE TRIAL BY LIGHT

SOLO WAS LED into the circular, fantastically illuminated room by two guards.

They pointed to a bare, highly polished table, told him to sit on it. When he did they stood at attention at his side.

The room was not large, perhaps like a surgery amphitheatre, with a judge's bench on a raised dais, with six judge's chairs behind it. The desk glistened and reflected; lights.

Near the table where Solo sat was another one similar to it, and as completely bare.

Above him, and around the room in an elevated semi-circle, looking down on the bench and the two tables in the cleared area were rows of empty chairs. But after a few moments three men entered from behind the bench and took their places in the center chairs.

Solo stared at them incredulous. Action of light from the desk blotted out their faces to him. The heads were blanked out, almost as if they were headless bodies.

When the three judges had taken their places, two men entered from each side of the room. One came to the table where Solo sat, the other went to the similar table near it. Lights blotted out the faces of these two men, too, no matter where they moved.

One of the guards touched Solo's shoulder, ordering him to place the 'death summons' before him on the bared table.

This folded sheet of paper was the only materials of the trial in evidence.

A voice from a speaker in front of the judges' bench droned, "Seated are three supreme justices of the highest court. The Highest Referendary of Unquestioned Supreme Hearings is now in session. All proceedings of this court are voice recorded. Seated with the accused is his defense attorney, appointed by the Court of Supreme Hearings."

One of the judges spoke. "The prosecution may open the case of World Order versus Napoleon Solo."

The man seated at the table near Solo got to his feet. The light, blotting his face from Solo's view, followed him.

The prosecutor stalked before the bench. "Prosecution will show that the defendant is guilty of all charges listed against him before this court."

A judge said, "We will dispense with the reading of those charges."

"I'd like to hear them read," Napoleon Solo said. His defense counsel shook his light-struck head at him, warning him to be silent.

A judge said coldly, "Defendant is permitted to speak only when it is time for him to admit to the charges proved against him in this court. Until this time he must remain silent and allow his defense attorney to speak for him. Only the defense attorney will be recognized by this court."

Solo shook his head, staring up at those light-blotted faces.

The voice from the speaker said, "Defendant will step into the witness chair."

A small chair inside a cage was eased out before the bench, suspended there. When Napoleon Solo protested, his defense attorney touched his arm warningly again and the guards placed Solo inside the cage. He sat down in the low chair so that his knees were almost up to his chest. The cage door was locked.

The defense attorney sat back at the table, apparently checking over the charges in the death summons.

The prosecutor said, "Do you admit that you came to this place with the avowed purpose of violence against the people herein?"

Solo started to answer, but the judges commanded him to silence. If an answer was required, they reminded him, his defense counsel would make it.

This gentleman remained silent at the defense table.

Solo sweated in the cage, raging against this mockery of justice. Still, he knew these men were deadly serious, listening to the further charges against him shouted by the prosecutor.

"You advocate the overthrow of our way of life by force?... You entered illegally?... You attacked and assaulted the person of two of our guards... You would destroy all that we here in this room hold dear?

"Are you not guilty of these charges? And are you not guilty of the further charges of planned murder? Treason? Spying? Are you not guilty?"

The defense attorney rose then, and spoke, for the first and only time during Napoleon Solo's trial. He said in a low, sad tone, "The defendant admits guilt to all these charges. He repents of his crimes against you. He is heartily sorry for his misdoings. But he understands there can be but one sentence in accord with justice; his crimes do not permit of even the recommendation of mercy.

"He throws himself upon the mercy of this court and asks only that he be allowed to die in the manner which will serve the cause of humanity under our great system most fully."

Solo stared. A judge spoke calmly. "There will be no need to hear from the defendant. The sentence is death, to be executed in a way most benefiting our inquiries into science."

TWO

SOLO WAS led to his cell. He felt nothing as far as the sentence of the strange court was concerned. They had never suggested the trial would be impartial. The summons had ordered him to a hearing of the treasonable charges leveled against him.

He prowled the cubicle, less concerned about what would happen to him than for the safety of Illya Kuryakin and Bikini.

Solo had not learned anything about Illya since he had seen him struck down by the light beam in the corridor. And Bikini?

He shook his head in anguish, not permitting himself to think about either of them.

The door opened, suddenly. Solo stared in complete astonishment, his mouth sagged open. Illya Kuryakin walked in.

Solo shook his head, feeling ill. It was Kuryakin—or Kuryakin's body. Illya was dressed in the green fatigues that all the guards wore, and his face was rigid, his eyes empty and staring.

Illya held a light-gun across his chest. He stared straight ahead, at nothing.

Solo gazed at him.

"Illya," he said.

Illya did not even hear him.

"No good to talk to him, Mr. Solo," Nesbitt's voice rattled the intercom. "He's gone quite beyond the reach of your voice."

Solo did not speak again, watching the way Illya stood, like a robot, a living dead man.

"Mr. Kuryakin is your guard, Mr. Solo. Isn't this a nice touch? Eh? I like it irony, Solo. You will die, when your turn comes, among my plants.

"Meantime, I warn you, Mr. Kuryakin has been programmed to kill you if you attempt to escape. An ironic touch that's lovely, eh, Solo?

"Surely you appreciate its grandeur? Guarded by your own former comrade, who is now one of my mindless slaves... Yes, if you try to escape, your own former friend will kill you. As I said, we indeed all of us have inside ourselves the seeds of our own destruction."

The intercom crackled a moment. "And now I am busy, Mr. Solo. You will forgive me if I leave you to the mercies of your former friend? I warn you, he has no memory, no stirring of memory of your past association. If you make a move to escape, or to attack him, he will kill you."

![Книга [Magazine 1966-12] - The Goliath Affair автора John Jakes](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-12-the-goliath-affair-232530.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-11] - The Volacano Box Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-11-the-volacano-box-affair-225337.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-05] - The Synthetic Storm Affair автора I. G. Edmonds](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-05-the-synthetic-storm-affair-180880.jpg)

![Книга Magazine 1967-07] - The Electronic Frankenstein Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-07-the-electronic-frankenstein-affair-178273.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-12] - The Pillars of Salt Affair автора Bill Pronzini](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-12-the-pillars-of-salt-affair-148925.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1966-06] - The Vanishing Act Affair автора Dennis Lynds](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-06-the-vanishing-act-affair-117180.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1966-09] - The Brainwash Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-09-the-brainwash-affair-50701.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-10] - The Mind-Sweeper Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-10-the-mind-sweeper-affair-42293.jpg)