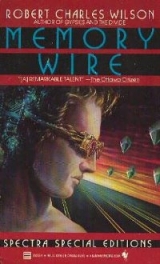

Текст книги "Memory Wire"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Соавторы: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

“No,” he said, and pulled back his hand. Teresa opened her eyes, shaken. Keller was staring grimly back. Some of this had seeped through to him, she thought, powerful images leaping the gap between them. His own memories. “I’m sorry,” she said hoarsely. She opened her hand and left the oneirolith on the table. The old Brazilian woman scuttled over with her tin box. “Passou a hora.” Their time was up.

It left her depressed. They walked back to the hotel in the aftermath of the rain, a sour humidity rising from the streets. Down the mouth of an alley Teresa glimpsed a posseiro woman, in transit or homeless, squatting among her possessions and suckling a naked child. The child had a thatch of dark hair, big eyes, Indio features. The woman cradled the child’s head in the crook of her arm and gazed down at him with an expression of unselfconscious affection that made Teresa turn away, suddenly weak. After what Keller had said about Byron, after what she had seen, she felt chastised. We are all down here hunting some grail, she thought, digging for it, scrabbling after it, not out of greed but out of our misplaced sincerity… and here was this illiterate woman crouched in an alley, certainly poor and probably homeless, but whole where they were broken (she felt it like a cold wind through her), healthy where they were crippled. It made her feel small; it made her feel ashamed.

The hotel lobby was full of stale warmth. In the room, Ng was waiting.

CHAPTER 7

When he was certain the Americans had left Brasilia, Stephen Oberg boarded a SUDAM flight directly to Pau Seco.

He had simply to flash his Agency card. SUDAM and the Brazilian government generally had been eager to cooperate. Technically—according to his documents—Oberg was a civilian employee of the DEA, but since the great amalgamation of the federal agencies in the thirties, the distinction had become obscure—his immediate superior was an NSA bureaucrat on lease to the security branch, and he was answerable to the Embassy.

The aircraft was crowded with peacekeepers in pea-green uniforms, talking among themselves in laconic Ariguaia Valley accents and oblivious to the dark ocean of forest below. Oberg propped his head on a pillow and pretended to sleep. He was 190 pounds, bulky in a gray suit, a plodding but methodical thinker. He was not given to fits of nerves, but he admitted that Brazil made him nervous.

There would have to be changes made. He had tried to impress that on the Agencies and on the government functionaries he had been introduced to in his brief time here. For years the mining of the Pau Seco artifact had been a relatively casual affair; smuggling happened mostly at the research facilities in America and the Asian states, where the oneiroliths were temptingly easy to duplicate. Smuggling from Pau Seco itself was problematic, and for years there had been no good reason to attempt it. The Eastern -Bloc had periodically made its presence felt, but that was to be expected… tolerated, even, within limits. The exigencies of the balance of power. But times had changed.

Oberg had been at the government labs in Virginia when the first of the new stones came in late last year. Technically, the research team leader told him, these new stones were more “addressable”—they interfaced more successfully with the cryptanalytical programs running out of the building’s big mainframes. “We’re downloading all kinds of material,” he said. “Ask for it, it’s there. It’s like an encyclopedia. A bottomless encyclopedia. But the effect on human volunteers …”

Oberg said, “It’s different?”

“Very idiosyncratic. Very strange. You should see.”

And so Oberg, who was the Agencies’ liaison-in-place, had followed the voluble team leader down a hallway to the small pastel rooms where the human volunteers were kept. This was essential research, too, Oberg had been told, though it made him queasy to think of it. Perversely, there were data the computers could not evince from the stones, data accessible to the living mind alone. Everything that was known about the Exotics had come through this route. A blue-skinned people who inhabited, or had inhabited, a small planet of a distant star. Through human volunteers some little knowledge of their language and anthropology had been eked out. But it was sporadic work, and much of it was contradictory, overlaid with dreams and wishes, the excrescences of the human mind.

The volunteer was a man named Tavitch. Like most of their volunteers, he came from the federal prison at Vacaville. Tavitch was a soft-spoken middle-aged man who had murdered his wife and two children a week after he lost his job as a data-base manager, and who chose the Virginia facility as an alternative to amygdalectomy. His eyes were large and moist, his expression faintly petulant. He held one of the new deep-core oneiroliths in his hand.

“First time he touched it, he was practically comatose,” the team leader burbled. “Oculogyric trance. Some kind of traumatic hypermnesia. But he’s relatively lucid now.”

Oberg folded his arms patiently. “Mr. Tavitch? Can you hear me?”

Tavitch looked up, though his expression was preoccupied.

“What do you see, Mr. Tavitch?” There was a long pause. “Time,” Tavitch said finally. “History.”

It was eerie, unpleasant. Oberg looked at the team leader. The team leader shrugged and waved his hands: go on.

Oberg sighed inwardly. “History,” he said. “Our history?”

“Our history,” Tavitch said, “their history. Ours is newer. Oh, it shines! You should see it. It’s like a river. A golden river of lives. Millions and millions, fading away back as many years.” His eyes were glazed and patient. “They’re ail in there…”

“Who?”

“Everybody,” Tavitch said. “Everybody?”

“The dead,” Tavitch said calmly. “Lives tangled up like strings. The living too—more like fuses. Burning.”

Oberg had shuddered. It was the instinctive revulsion he inevitably felt in that room. A sense of contamination. People assumed the oneiroliths had been tamed, that their familiarity had taken the edge off their strangeness. For Oberg, at least, it wasn’t even remotely true. They were the product of an intelligence that was profoundly and dissonantly inhuman. You could tell by looking at them—the oily shine of them, the illusion of depth. Stone mechanism, he thought. Mineral life. It made him uneasy.

“They’re in here too,” Tavitch said, and his voice descended now into a minor key.

“Who, Mr. Tavitch?”

“ Alma. Peter. Angela.” The convict’s face seemed to collapse into itself. Oberg was stunned. He thought the man might cry—Tavitch, the murderer, who had never demonstrated any sign of remorse. “They want to understand,” Tavitch said, “but they don’t… they can’t…”

Oberg left the room, repelled.

Alma, Peter, Angela.

They were Tavitch’s family … the ones he had killed.

Later, over lunch in the sterile staff cafeteria, the team leader had tried to talk away the event. “You understand, we’re working here with selected subjects. Criminals. Murderers, like Tavitch. So the work has a certain bias built into it. Conventional research hasn’t given us everything we’re looking for. We’re very little closer to understanding who the so-called Exotics are, or how an oneirolith interacts with the mind—or why—than we were fifteen years ago.”

“It’s unnatural,” Oberg had-said. “It’s ugly.”

The team leader blinked. “I follow your concerns, Mr. Oberg. All I’m suggesting is moderation. Patience. Look at it from our point of view. Communication is what we’re all concerned with here. And communication—of one kind or another—is what happened in that room with Tavitch. There’s this prejudice against what’s called ‘the human interface,’ the effect of the oneiroliths on the human mind. Well, obviously it’s a difficult study. The effect is subjective. You can’t measure it or calibrate it. So we do a limited kind of research, and we have to compete for funding with people who are downloading much harder data. You see what I’m driving at? I know you had a negative reaction to what happened today, but I wouldn’t want that to affect the course of our work.”

So it comes down to this, Oberg had thought: this man’s, career. “I don’t control funding.”

“You have influence.”

“Only a little.”

“Still, I’m convinced we’re doing important work, vital work, with these new stones. No one wants to consider it, Mr. Oberg, but maybe the real message the Exotics left us isn’t strictly linguistic. Maybe it’s preverbal. Maybe it operates on the level of intuition … or emotion … or memory.”

Memory. What was it Tavitch had said? Something about history. And the team leader had talked about hypermnesia, an involuntary upwelling of the past. To Oberg all of this seemed obviously, patently sinister. The past was the past, a burial place, the tomb of events, and better that way. Nobody cared about the past but priests and poets. You did a thing and you left it behind you. Hypermnesia, he thought, Tavitch’s “history,” was a light cast into places that by all rights should have been dark, hidden, buried.

Briefly, Oberg felt a wave of what the Army psych officers had called “depersonalization”—a sense of standing apart from himself, a disconnection. For one crystalline moment he understood that his horror of the alien stones might be purely personal, a pathology, a self-disgust as profound as he had seen in Tavitch this afternoon. A phobia of memory. He gazed at the bland, pale face of the man across the table and thought: if you’d seen what I’ve seen —if you’d done what I’ve done—

But it was a progression of logic he could not allow, and he thrust it from his mind. The oneiroliths were evil; there was no other possibility.

“Just trying to clarify our position,” the team leader said.

“I understand,” Oberg told him.

He woke from the reminiscence as if it had been a bad dream.

The aircraft was circling now, the sky lightening with dawn. The uniformed peacekeepers were mostly asleep. Oberg imagined he could feel it coming nearer—the source of the virus, the center of the infection. He did not think the analogy was unfair. It bred like a virus; it insinuated itself into the body—or at least the mind—like a virus. Like a virus, it had purposes of its own. Not human purposes.

He peered out the window and saw the dust of Pau Seco, pale in the morning light, rising from a canyon in the jungle.

CHAPTER 8

1. “It looks like hell,” Keller said.

“It is hell,” Ng said blithely. “But this isn’t the worst of it.”

They had come in along the broad highway from Cuiaba. Ng drove a battered Korean semi full of refrigerated meat —it was his day job, he said. He ran supplies to the box cities full of hopeful foraos and unlucky formigas. It paid okay, he said. He did not say what his night job was.

It was a long run from Cuiaba. Teresa and Byron napped in the rear of the huge cab; Keller sat up with Ng. Ng didn’t talk much but Keller was able to confirm his suspicion that the man had been a soldier, one of the Vietnamese commandos who had fought in the Pacific Rim offensive. Keller had always been just a little scared of the Vietnamese. They were culled soldiers, tagged at birth and raised in the big military creches outside Danang. Their bodies produced chronically high levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, chronically low levels of monoamine oxidase. They were, in other words, aggressive, domineering, and desperate for excitement. It was there in the way Ng drove his rig: too fast, but with a tight, rapt smile. And when he turned a corner and the sleeve rode up his arm, Keller recognized the faint blue double-X etched under the skin—the Danang tattoo.

They approached Pau Seco a little after dawn. Keller saw the plume of dust on the horizon feathering toward the south. “Pau Seco?” he said, and Ng nodded. Within an hour they had reached the outskirts of the old town, the endemic poverty of Brazil but on a grander scale. Shacks rolled up and down these bread-loaf hills, all nearly identical, random configurations of corrugated tin, tarpaper, cardboard. Keller gazed at the emaciated men gathered by the road, who returned his gaze without curiosity as the big rig rumbled past.

“Formigas,” Ng said. “Unlicensed miners. Most of them are not even that, actually. They come in the hope that they’ll be hired into the mine. The garimpeiros are the men who own the land. They hire the formigas to do their work for them. For wages, or more likely a share of the income. If there is ever any income. But there are more of these people than there is work for them. Most of them spend their days in the laborers’ compound hoping someone else dies. It’s the best way to get work.”

And then they topped a rise and Keller saw the mine itself.

Pau Seco, he thought. The ugly center of the world.

Ng pulled the truck into the bay back of a cinderblock building and climbed out, dusting his shorts with his small hands. He led Keller to the crest of a hill and gestured almost proudly at the pit of the mine. “Hell,” he said.

It might have been hell. It was an open canyon of red mud and white clay so immense that the trees on the far rim were gray with distance. Keller did a professional pan, sweeping the mine east to west so that this vista could be reclaimed from his AV memory. There was so awesomely much of it.

“This was a plain once,” Ng said. “A plain covered with jungle. Then the garimpeiros came, and the foreigners, and the government to take their twenty-five percent. When they burned off the trees, the ashes fell for miles around.”

It was a vista from another century, formigas creeping up the inclines like the ants they were named for, deafening with the clangor of hand tools and human voices. This was how the Aztecs must have mined their gold, Keller thought, and he felt a moment of giddy vertigo: an abyss here, too, of time.

Ng occupied a shack in the old town of Pau Seco with a view commanding the mine and the sprawl of the workers’ compound. After nightfall the old town came alive. The town of Pau Seco, Ng explained, was a concentration of whorehouses, banks, and bars. Every day one or two of these thousands of garimpeiros would come into money; the town existed to extract it from them. Periodically there was the sound of gunfire.

Keller sat out on the wooden vestibule of the shack, drinking cautiously from a bottle of white cachaca and listening as Ng explained the trouble they were in.

His English was easy, flat, American in inflection. “I don’t know Cruz Wexler.” He shrugged. “Cruz Wexler means nothing to me. Two months ago I was approached by a man, he said he was a surveyor working for SUDAM. A Brazilian. He had SUDAM credentials, he had a nice suit. He said there was a buyer interested in acquiring a deep-core stone and was it possible I could set this up?” He stretched out across the three risers that connected his wooden shack to the mud, plucked at a hole in his T-shirt. “Well, it isn’t easy. Security is very tight. They named a figure, the figure was attractive, I said I would do what I could.”

“It’s arranged?” Byron asked hopefully.

“You should have the stone tomorrow. The thing is best done quickly. But you have to understand… you came here as couriers, right?”

Byron said, “We take the stone, we carry it out of the country…”

“Nobody told you it might be dangerous?”

“We have documents—”

“Paper.” Ng shrugged. “If it was that easy, any forao with brains would be walking out of here wealthy.” He grinned. “There’s not much smuggling because the military is in charge. Mostly, you can do what you want in the old town. But the military is there, and they carry guns and they use them. The official penalty for the crime we’re discussing is death. What it means is summary execution. A trial would be”—and the smile widened—“very unusual.”

“Son of a bitch,” Byron said. “It’s a walk, he says, it’s a fucking vacation^. It’s a walk through the fucking cemetery is what it is!”

Teresa said quietly, “It’s all right.”

“He fucked us over!”

“Byron, please—”

“Goddamn,” Byron said. But he sat down. She turned to Ng. “If it’s so dangerous, why did you agree to get involved?”

Ng sat back, hugging his knees. “I’m easily bored,” he said.

2. Oh, but I can feel it now, Teresa thought.

In the midst of this brutality it was so close. She felt it like a pain inside her, like the poignancy of old loss, a kind of melancholy.

She lay in the darkness of Ng’s small shack, curled on a reed mat at the heart of the world.

Melancholy, she thought, but also—she could begin to admit it—frightening. She was not as naive as Byron seemed sometimes to think, but the mine had taken her by surprise … the brutality, the squalor of it, the lives that were lost here. It was not meant to be this way, she thought.

She sat up in the darkness. Through the paneless window she could see Pau Seco sprawling at the foot of this moonlit hill. Oil-can fires burned sporadically like stars in the darkness.

She thought of the Exotics, the winged people she had seen so often in her ’lith visions. She was not afraid of them; the impression of their benevolence was strong and vivid. But they were different. There was something essentially unhuman about them, she thought—something more profound than the shape of their bodies.

They would not have created Pau Seco. They would not have expected it to be created.

She lay back in the darkness, weary and confused.

It had not been wholly her own idea to come here. It was an imperative she felt more than understood, a kind of homing instinct. Her own history faded back into darkness, lost in the fires that had swept the Floats fourteen years ago. Her childhood was a mystery. She had come into the Red Cross camps scalded and smoke-blinded and nearly mute. She had been cared for—adopted, though it was never legal—by an extended family of Guatemalan refugees; they fed her, clothed her, and practiced their English on her. They named her Teresa.

She was grateful but not happy. She remembered those days as a haze of pain and loss: the searing conviction that something valuable had been stolen from her. She became attached to a rag doll named Amy; she screamed if the doll was taken away. When Amy fell into a canal and disappeared beneath the oily seawater, she wept for a week. She adjusted to her new life in time, but the nameless pain never went away… until she discovered the pills.

One of her Guatemalan family, a hugely fat middle-aged woman named Rosita—whom the others called tia abuela—brought the pills home from the public health clinic. Rosita suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and took the pills for, as she put it, “ree-lif.” They were narcotic/analgesics keyed to the opiate receptors in the brain; Rosita was frankly addicted but, the clinic told her, the pills did not create a tolerance … the addiction would not get worse, they said, and that was good, because the arthritis would not get better.

Teresa, alone one afternoon in their antiquated houseboat, stole a pill from Rosita’s bottle and hid it under her pillow. The act was impetuous—partly curiosity, partly a dim intuition that the pill might work for her the kind of magic it worked for Rosita. In bed that night she swallowed it.

The effect was instantaneous and profound. Inside her a huge and unsuspected tide of fear and guilt rolled back. She closed her eyes and relished the warmth of her bed, smiling for the first time in years.

Tia Rosita was right, she thought. Ree-lif.

Rosita collected her prescription twice a month. Twice a month, Teresa took one off the top. Rosita did not seem to notice the thievery, or if she did, she did not suspect Teresa. And Teresa did not dare take more, for fear of drawing attention to herself.

Still, she lived for these moments. The pills seemed to detonate inside her, tiny explosions of purity and peace. Words like loneliness and loss began to make sense to her; she realized for the first time that they might not be permanent or universal.

When she was sixteen one of the boys she had come to think of as her brother, a rangy twenty-year-old named Ruy, took her out to the empty margin of the tidal dam and showed her a fistful of pink-and-yellow spansules—the same kind Rosita got from the clinic.

She could not help herself. She grabbed. Ruy pulled his hand away, laughing; a cloud of sea gulls whirled up from the concrete pilings. “Right,” he said. “I thought so.”

She stared covetously at his clenched fist. “You can get those?”

“Many as I want.”

“Can I buy them?”

“Acaso.” He shrugged loftily. Maybe.

“How much?”

“How much you got?”

She had nothing. She had been going to the charity school up in the North Floats, where her English teacher called her “a good pupil” and her art instructor called her “talented.” But she didn’t care about the school. She could quit, she thought, get a job, get some money… acaso.

“When you do,” Ruy said—walking away, heartbreakingly, with the pills still imprisoned in his hand– “then you talk to me.”

But Rosita, older and more gnarled but no less vigilant, wouldn’t let her leave school. “What kind of job are you going to get? Be a whore down by the mainland, like your sister Livia?” She shook her head. “Public Works is pulling out of this place, you know. Too many uncertified people. No documents, no green cards, no property deeds. You’re lucky you have a school. Maybe won’t have one much longer, you think about that?”

But it was Rosita’s anger and not any practical consideration that deterred her. She stayed in school, maintained her habit, and ignored Ruy when he taunted her with his apparently endless supply of drugs. Until, one day, her art instructor complimented her on a collage she had assembled. She had a real talent, he said. She could go somewhere with it.

It was a strange idea. She enjoyed putting together collages and sculptures, it was true; sometimes it felt almost as good as the pills made her feel. It was almost as if someone else were doing the work with her hands, some part of her she had lost in the fire, maybe, making its presence felt. She would abandon herself to the work and find that hours had passed: it was a good feeling.

She had not thought of making money with it. It looked like an outside chance. Still, she packed a bag lunch one Sunday and hiked along the pontoon bridges to the mainland, to the art galleries up the coastal highway. The mainland frightened her. She was not accustomed to the roaring of trucks and automobiles; in the Floats you saw mostly motor launches, and those only in the big canals. And there was the eerie solidity of the ground beneath her feet, rock and sand and gravel wherever she turned.

She examined the artwork offered for sale in these landlocked places. Crystal paintings, junk sculptures, polished soapstone. Most of it had come from the Floats and was considered—she inferred from the way people spoke —a kind of folk art. Some of the pieces were very good and some were not, but she realized with a degree of surprise that her art instructor had been right—there was nothing here beyond her talents. She lacked the tools to tackle some of these projects, but the work she had done with scrap metal salvaged from the dumpboats was as good as at least half of what she had seen that day. Possibilities here, she thought.

Two weeks later she carried three small pieces across the pontoon and chain-link bridges to a place called Arts by the Sea. She showed them to the owner, a woman only slightly younger than Rosita. The woman was named Mrs. Whitney, and she was skeptical at first, but then—as Teresa unwrapped the oilcloth from her work—impressed. Her eyes widened, then narrowed. “Such mature work!” She added, “For someone your age.”

“You’ll buy it?” Teresa asked.

“We sell on commission. But I can offer you an advance.”

It was, Teresa learned later, a pittance, a token payment; but at the time it was more money than she had seen in one place.

She took it to Ruy and offered him half of it. He gave her enough pills to fill up both her cupped hands. That night she took two.

Ree-lif. It flowed through her like a river. She rationed herself to one a night, to make them last, and worked in her spare time on another sculpture for Mrs. Whitney. Mrs. Whitney paid her almost double for it, and that was good; but Ruy’s prices had begun to escalate too. She paid but she hated him for it. Ruy had become suddenly important to her, and she acquired the habit of observing him. He moved down the pontoon alleys swaggering, his bony hips thrust forward. “Muy macho,” Rosita always said when he struck these poses at home, but out here there was no one to deflate him. He hung around with his similarly hipshot friends by the graffiti-covered tidal dam; she had seen him dealing pills there. One afternoon—nursing her hatred– she cut classes and followed him halfway to the mainland, to a tiny pontoon shack listing in the North Floats, a gasoline pump gushing out bilge into the dirty canal beside it. Ruy went in with his hand on his wallet and came out clutching a fat paper bag.

She summoned up all her courage and, when she was certain Ruy was truly gone, knocked at the door of the shack.

The man who answered was old, thin, hollow-looking. He peered at her a long time—her mouth was too dry to speak—and said at last, “What the fuck do you want?”

“Pills,” she said, panicking.

“Pills! What makes you think I got pills?”

“Ruy,” she said desperately. “Ruy is my brother.”

His expression softened. “Well,” he said. “Ruy’s little sister cutting out the middleman.” He nodded. “Ruy’d be pissed off, I bet, if he knew you were here.”

“I can pay,” she said.

“Tell me what you want.”

She described the pink-and-yellow spansules.

“Yeah,” he said. “If that’s what you want. It’s a waste of money, though, you ask my opinion.” He rummaged in a drawer in an old desk at the back of his single precariously listing room; she watched from the doorway. “You might like these better.”

They were small black-coated pills in a paper envelope, maybe a hundred in all. Teresa regarded them dubiously. “Are they the same?”

“The same only more so. Not just pain pills, hm? Happy pills.”

Flustered, she gave him her money. It occurred to her during the long walk back that she might have made a fool’s bargain, the pills might be coated sugar. Or worse. That night, in bed, she was not sure whether she should try even one. What if they were toxic? What if she died?

But she had run out of Ruy’s spansules and she dared not pilfer more of Rosita’s. The need overcame her reluctance; she swallowed a black pill hastily.

Pleasure spread out from the pit of her stomach. It was, gradually and then overwhelmingly, everything she could have wanted: the satisfaction of a successful piece of artwork, the satisfaction that came from being loved, the satisfaction—this perhaps the best of all—that came from forgetting. Afloat on her mattress, rocking in the slow swell, she might have been the only person in the world. She loved the new pills, she thought. They were better. Yes. And one was enough. At least at first.

She lived happily with these arrangements for months, selling enough work to Mrs. Whitney to keep her supply up, idling through the days—she had begun to take a pill each morning too—as if they were hours. She felt she could have continued this way indefinitely if it were not for Ruy, who had been cheated out of his immense profit on the cheap pink-and-yellow spansules and who had discovered her arrangement with his supplier. He retaliated by leading Rosita to Teresa’s pill box, concealed behind a broken floorboard under the bed. Tia abuela Rosita was both angry and hurt, and made a demonstration of washing the pills down the Public Works conduit one by one. Teresa was so shocked to see her store of happiness flushed away that she displayed no emotion, merely packed her things, took what remained of her gallery money, and left.

(Years later she tried to return, with the idea of making some kind of apology to Rosita, achieving some sort of reconciliation … but the neighborhood had grown much worse, and her Guatemalan family had gone away. Just packed and left one day, an elderly neighbor told her, nobody knew where or what happened to them—except for that Ruy, of course. He had been killed in a knifefight.)

She put together a makeshift studio in the Floats off Long Beach, invested some money in supplies, acquired a new source for the small black pills. She learned that they were laboratory synthetics, synthetic enkephalins, very potent and very addictive. But that didn’t matter: she could handle it. She knew what she was doing. She began to meet other Float artists and understood that she was not alone, that many of them depended on chemical pleasures in one form or another. Some of them even used Exotic stones, the oneiroliths from the Brazilian mines. But that was different, she thought; too strange—not the thing she wanted.

She could not say exactly when her habit got out of hand. There was no border she crossed. It didn’t interfere with her work; strangely, the opposite was true. It was as if the thing inside her that created art was spurred on by her addiction—the way a dying tree will sometimes produce its most copious fruit.

She did sometimes, in her lucid moments, notice a kind of deterioration. She perceived this as a change, not in herself, but in her environment. Her studio was suddenly smaller: well, yes, she had moved into a cheaper one, saving rent. Her image in the mirror was gaunt: food economies, she thought, making her money go a little further. It proceeded in such gradual increments that nothing seemed to happen—nothing at all—until she was alone in a corner of an ancient bulk-oil terminal with a dirty mattress and a jar of medication. A jar of happiness.

She knew it was killing her. The idea that she was dying eased into her mind so cleverly that it seemed to appear wholly formed and yet familiar. Yes, she thought, I am dying. But maybe dying in a state of grace was better than living in a condition of unrelieved pain. Maybe it was a kind of bill come due at last: maybe, she thought, I should have died in the fire.