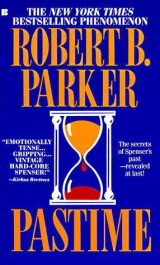

Текст книги "Pastime"

Автор книги: Robert B. Parker

Жанр:

Крутой детектив

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

CHAPTER 21

PEARL didn't like the rain. She hung back when Susan and I took an after-dinner stroll, even when Susan pulled on her leash. And when we prevailed through superior strength, she kept turning and looking up at me, and pausing to jump up and put her forepaws on my chest and look at me as if to question my sanity.

"I heard that if you step on their back paws when they jump up like that, they learn not to," Susan said.

"Shhh," I said. "She'll hear you."

Susan had a big blue and white striped umbrella and she carried it so that it protected her and Pearl from the rain. Pearl didn't quite get it, and kept drifting out from under its protection and getting splattered and turning to look at me. I had on my leather trench coat and the replica

Boston Braves hat that Susan had ordered for me through the catalogue from

Manny's Baseball Land. It was black with a red visor and a red button.

There was a whiteB on it and when I wore it I looked very much like Nanny Fernandez.

"What will you do?" Susan said.

"I'll try to extract Patty Giacomin from the puzzle and leave the rest of it intact."

"And you won't warn Rich?"

"No need to warn him. He knows he's in trouble."

"But you won't try to save him?"

"No."

"Isn't that a little flinty?" Susan said.

"Yes."

"Officially, here in Cambridge," Susan said, "we're supposed to value all life."

"That's the official view here in Cambridge of people who will never have to act on it," I said.

"That is true of most of the official views here in Cambridge," Susan said.

"My business is with Patty-Paul really. Rich Beaumont had to know what he was getting himself into-and besides I seem to feel a little sorry for

Joe."

Pearl had wedged herself between my legs and Susan's, managing to stay mostly under her part of Susan's umbrella, and while she didn't seem happy, she was resigned. We turned the corner off Linnaean Street and walked along

Mass Avenue toward Harvard Square.

"You are the oddest combination," Susan said.

"Physical beauty matched with deep humility?"

"Aside from that," Susan said. "Except maybe for Hawk, you look at the world with fewer illusionsthan anyone I have ever known. And yet you ire as sentimental as you would be if the world were pretty-pretty."

"Which it isn't," I said.

"You cook a good chicken too," Susan said.

"Takes a tough man," I said, "to make a tender chicken."

"How come you cook so well?"

"It's a gift," I said.

"One not, apparently, bestowed on me."

"You do nice cornflakes," I said.

"Did you always cook?" she said.

Pearl darted out from under the umbrella long enough to snuffle the possible spoor of a fried chicken wing, near a trash barrel, then remembered the rain and ducked back in against my leg.

"Since I was small," I said.

As we passed Changsho Restaurant, Pearl's head went down and her ears pricked and her body elongated. She had found the lair of the chicken wings she'd been tracking earlier.

"Remember," I said, "there were no women. Just my father, my uncles, and me. So all the chores were done by men. There was no woman's work. There were no rules about what was woman's work. In our house all work was man's work. So I made beds and dusted and did laundry, and so did my father, and my uncles. And they took turns cooking."

We were past Changsho, Pearl looked back over her shoulder at it, but she kept pace with us and the protective umbrella. There was enough neon in this part of Mass Avenue so that the wet rain made it look pretty, reflecting the colors and fusing them on the wet pavement.

"I started when I was old enough to come home from school alone. I'd be hungry, so I'd make myself something to eat. First it was leftovers-stew, baked beans, meat loaf, whatever. And I'd heat them up. Then I graduated to cooking myself a hamburg, or making a club sandwich, and one day I wanted pie and there wasn't any so I made one."

"And the rest is history," Susan said.

A big MBTA bus pulled up at the stop beside us, the water streaming off its yellow flanks, the big wipers sweeping confidently back and forth across the broad windshield.

"Well, not entirely," I said. "The pie was edible, but a little odd. I didn't like to roll out the crust, so I just pressed overlapping scraps of dough into the bottom of the pie plate until I got a bottom crust."

"And the top crust?"

"Same thing."

The pneumatic doors of the bus closed with that soft, firm sound that they make and the bus ground into gear and plowed off through the rain.

"My father came home and had some and said it was pretty good and I should start sharing in the cooking. So I did."

"So all of you cooked?"

"Yeah, but no one was proprietary about it. It wasn't anyone's accomplishment, it was a way to get food in the proper condition to eat."

"Your father sounds as if he were comfortable with his ego," Susan said.

"He never felt the need to compete with me," I said. "He was always very willing for me to grow up. Ї

Pearl had located a discarded morsel of chewing gum on the pavement and was mouthing it vigorously. Apparently she found it unrewarding, because after a minute of ruminative mouthing she opened her jaws and let it drop out.

"There's something she won't eat," Susan said.

"I would have said there wasn't," I said.

We passed the corner of Shepard Street. Across Mass Avenue, on the corner of Wendell Street, the motel had changed names again.

"I got to shop some too," I said, "though mostly for things like milk and sugar. My father and my uncles had a vegetable garden they kept, and they all hunted, so there was lots of game. My father liked to come home after ten, twelve hours of carpentering and work in his garden. My uncles didn't care for the garden much, but they liked the fresh produce and they were too proud to take it without helping, so they'd be out there too. Took up most of the backyard. In the fall we'd put up a lot of it, and we'd smoke some game."

"Did you work in the garden?" Susan said.

"Sure."

"Do you miss it?"

"No," I said. "I always hated gardening."

"So when we retire you don't want to buy a little cottage and tend your roses?"

"While you're inside baking up some cookies," I said, "maybe brewing a pot of tea, or a batch of lemonade that you'd bring me in a pitcher."

"What a dreadful thought," Susan said.

"Yes," I said. "I prefer to think I can be the bouncer in a retirement home."

The Cambridge Common appeared through the shiny down-slanted rain. Pearl elongated a little when she sniffed it. There were always squirrels there, and Pearl had every intention of catching one.

"And you?" I said.

"When I retire?"

"Yeah."

Susan looked at the wet superstructure of the children's swing set for a moment as we crossed toward it.

"I think," she said, "that I shall remain young and beautiful forever."

We reached the Common and Pearl was now in low tension, leaning against the leash, her nose apparently pressed against the grass, sniffing.

"Well," I said, "you've got a hell of a start on it."

"Actually," she said, "I don't suppose either of us will retire. I'll practice therapy, and teach, and write some. You'll chase around rescuing maidens and slaying dragons, annoying all the right people.

"Someday I may not be the toughest kid on the block," I said.

She shook her head. "Someday you may not be the strongest," she said. "I suspect you'll always be the toughest."

"Good point," I said.

CHAPTER 22

PAUL and I were working out in the Harbor Health Club. Paul was doing pelvic tilt sit-ups. I could do some. But Paul seemed able to do fifty thousand of them and had the annoying habit of pausing to talk during various phases of the sit-up without any visible strain. He was doing it now.

"Maybe," he said, "we were out in Lenox asking the wrong questions of the wrong people."

I was doing concentration curls, with relatively light weight, and many reps. Paul had been slowly weaning me from the heavy weights. It's the amount of work, not the amount of weight.

"Almost by definition," I said, trying to sound easy as I curled the dumbbells. "Since what we did produced nothing."

"Well, I mean I know I'm a dancer and you're a detective, but…"

"Go ahead," I said. "If you've got a good idea, my ego can stand it-unless it's brilliant."

"It's not brilliant," Paul said. He curled down and up and down again, and began curling up on an angle to involve the lateral obliques. "But if I had more than a million dollars in cash, and I were running away from the kind of people you've described, maybe I wouldn't stay in a hotel."

I finished the thirtieth curl and began to do hammer curls.

"Because you wouldn't be making a temporary departure," I said.

"That's right," Paul said. "You'd know you could never come back."

"So maybe you'd buy a place, or rent a place."

"Yes. I don't know what property costs, but if I had a million dollars.. ."

"More than a million," I said. "Yeah. You'd stay in a hotel if you were on your way somewhere. But if you were going to make it a permanent hideout, you'd want something more."

"Could you buy a place without proving your identity?" Paul said.

I put down the barbells. They were bright chrome. Everything was upscale at the Harbor Health Club except Henry Cimoli, who owned it. Henry hadn't changed much since he'd fought Willie.Pep, except that the scar tissue had, with time, thickened around his eyes, so that now he always looked as if he were squinting into the sun.

"You'd have to give a name, but if you were paying cash, I don't think you'd have to prove it."

"So maybe we should go out there and talk to real estate people," Paul said. "Yes," I said. "We should."

I finished my set of thirty hammers and went back to straight curls, concentrating on keeping my elbow still, using only the bicep.

"It's an excellent idea," I said.

Paul had gone into a hamstring stretch where he sat on the floor with his legs out straight and pressed his forehead against his kneecap.

"You'd have thought of it anyway," he said.

"Of course," I said. "Because I'm a professional detective, and you're just a performer."

"Certainly," Paul said.

We finished our workout, stretched, took some steam, showered, picked up

Pearl from the club office where she had been keeping company with Henry, and strolled out into the fresh-washed fall morning feeling loose and strong with all our pores breathing.

In the car I said, "Is there a picture of your mother?"

"Should be, at the house."

"Okay, let's go out there and break in again and get it."

"No need to break and enter," Paul said. "While we were there last time I got a key. She always was losing hers, so she kept a spare one under the porch overhang. I took it when we left."

We went out Storrow Drive toward Route 2. A little past Mass General

Hospital I spotted the tail. It was a maroon Chevy, and it was a very amateurish tail job. He kept fighting to stay right behind me, making himself noticeable as he cut in and cut off drivers to stay near my rear bumper. There was even horn blowing.

I said to Paul, "We are being followed by one of the worst followers in

Boston."

Paul turned and looked out the back window.

"Maroon Chevy," I said.

"Right behind us?"

"Yeah. Probably someone from Gerry," I said. "Joe would have someone better. If Vinnie Morris did it you wouldn't notice."

"Would you?"

"Yeah."

"What are we going to do?"

"We'll lose them," I said.

We continued out Storrow and onto Soldiers Field Road, past Harvard Stadium and across the Eliot Bridge by Mt. Auburn Hospital. In the athletic field near the stadium a number of Harvard women were playing field hockey. Their bare legs flashed under the short plaid skirts and their ankles were bulky with thick socks. The river as we crossed it was the color of strong tea, and a little choppy. A loon with his neck arched floated near the boat club. Behind us the maroon Chevy stayed close to our exhaust pipe. I could see two people in it. The guy driving was wearing sunglasses. Near the

Cambridge-Belmont line, where Fresh Pond Parkway meets Alewife Brook

Parkway there is a traffic circle. I went slowly around it with the Chevy behind me.

"Where we going?" Paul said.

"Ever see a dog circle a raccoon or some other animal it's got out in the open?"

"No."

I went all the way around the circle and started around again.

"They keep circling faster and faster until they get behind it," I said.

I held the car in a tight turn and put more pressure on the accelerator.

The Chevy tried to stay tight, but he didn't know what was going on and I did. Also I cornered better than he did. He lost some ground. I pushed the car harder, it bucked a little against the sharpness of the turn but I held it in.

"I get it," Paul said.

"Quicker than the guy in the Chevy," I said. He was still chasing us around the circle. On the third loop I was behind him and as he started around again, I peeled off right and floored it out the Alewife Brook Parkway, past the shopping center, ran the light at Rindge Avenue by passing three cars on the inside, and headed up Rindge back into Cambridge. By the time

I got to Mass Avenue he had lost us. I turned left and headed out toward

Lexington through Arlington.

"Wily," Paul said.

"Float like a butterfly," I said. "Sting like a bee."

"Pearl's looking a little queasy," Paul said.

"Being a canine crime stopper," I said, "is not always pretty."

CHAPTER 23

WE started in Stockbridge, because Paul and I agreed that Stockbridge was where we'd buy a place if we were on the run. And it was easy. We left Pearl in the car with the windows part open diagonally across from the Red Lion

Inn, walked across the street to the biggest real estate office on the main street in Stockbridge, and showed the picture of Patty Giacomin to a thick woman in a pair of green slacks and a pink turtleneck.

"Oh, I know her," the woman said. "That's Mrs. Richards. I just sold them a house."

The house she had sold them was about half a mile from town on Overlook

Hill. They had purchased the house for cash under the name Mr. and Mrs.

Beaumont Richards.

"Beaumont Richards," I said as we drove up the hill. "Who'd ever guess it was him?"

Paul was silent. His face seemed to have lost color, and he swallowed with difficulty. Pearl had her head forward between us, and Paul was absently scratching her ear.

I parked on the gravel at the edge of the roadway in front of the address we'd been given. It was a recently built Cape, with the unlandscaped raw look that newly built houses have. This one looked even rawer because it was isolated, set into the woods, away from any neighbors. The roadway that we parked on continued into the woods. As if, come spring, an optimistic builder would put up some more houses for spec. Running up behind the house were some wheel ruts which appeared to do service as a driveway. The ruts had probably been created by the builders' heavy equipment and would be smoothed out and re-sodded in spring. To the left the hill sloped down toward the town, and you could see the Red Lion Inn, which dominated the minimalist center. Behind the house the woods ran, as best I could tell, all the way to the Hudson River.

"How to do this?" I said.

"I think I should go in," Paul said.

"Yeah, except Beaumont is bound to be very nervous about callers," I said.

"I'm his paramour's son," Paul said. "That's got to count for something."

"He's scared," I said. "That counts for everything in most people, if they're scared enough."

"I have to do this," Paul said. "I can't have you bring me in to see her.

I am a grown man. She has to see me that way. She has to accept that… that I matter."

He swallowed. He had the look of bottled tension that he'd had when I first met him.

I nodded. "I'll be here," I said.

Paul made an attempt at a smile, gave me a little thumbs-up gesture, and got out of the car. Pearl immediately came into the front seat and sat where Paul had sat.

I watched him walk up the curving flagstone pathway toward number 12. It had a colonial blue door. The siding was clapboard stained a maple tone.

There were diamond panes in the windows. There was no lawn yet, but someone had put in a couple of evergreen shrubs on each side of the front door and a quiet breeze gently tossed the tips of their branches. I wished I could do this for him. It cost him so much and would cost me so little. But it would cost him much more if I did it for him. He stopped on the front steps and, after a moment, rang the doorbell.

The door opened and I could see Paul speak, and pause, and then go in. The door closed behind him. I waited. Pearl stiffened and shifted in the seat as a squirrel darted across the gravel road and into the yellowing woods that had yielded only slightly to the house. I rubbed her neck and watched the front door.

"Life is often very hard on kids, Pearl," I said.

Pearl's attention remained fixed on the squirrel.

There was no sound. And no movement beyond that which the breeze caused to stir in the forest. Beaumont had chosen a bad place to hide. It seemed remote but its remoteness increased his danger.He'd have been better off in a city among a million people. Out here you could fire off cannon and no one would hear.

Pearl's head shifted and her body stiffened. The front door opened and

Patty Giacomin came down the front walk with a welcoming look on her face.

She still looked good, very trim and neat, with her blonde hair and dark eyes. She was dressed in some kind of Lord Taylor farmgirl outfit, long skirt over big boots, an ivory-colored, oversized, cableknit sweater, and her hair caught back with a colorful headband.

I rolled the window down on the passenger side halfway so I could speak to her. Pearl, who was standing on all fours now in the front seat, thrust her head through the opening, her tail wagging.

"Well, hello, you beautiful thing," Patty said and put a hand out for Pearl to sniff. "And you, my friend," she said to me. "How can you sit out in the car like a stranger? Come in, meet Rich, see my new house. It's been too long."

I nodded and smiled. "Nice to see you, Patty," I said and got out of the driver's side. Pearl turned toward me and looked disappointed when I closed the door on her. I went around the car and Patty Giacomin gave me her cheek to kiss.

"Come on in," she said again. "And bring this lovely dog. I couldn't bear it if she had to sit out here all alone, while we're all up in the house visiting."

I opened the passenger door and Pearl jumped out and dashed around in front of the house withher nose to the ground until she found a spot where she could squat. Which she did. I stuck her leash in my hip pocket.

Patty took my hand as if we used to be lovers, and led me to the front door. Pearl joined us there, and when Patty opened it, pushed in ahead of us. Paul was in the living room with a guy that looked like a People magazine cover boy. The living room was what I expected it would be. Knotty pine paneling, big fieldstone fireplace. Beams, wooden furniture with colonial print upholstery, a braided rug on the floor.

"Rich," Patty said, "I'd like you to meet someone," and gestured me toward him like I was the ambassador from Peru. Rich put out his hand and I took it. He didn't seem very pleased.

"Coffee?" Patty said. "A drink? Paul, do you drink now?"

Paul said, "Yes, I do, but not right now, thanks."

I shook my head. Rich was leaning against the wall near the fireplace with his arms folded. He was probably my height, which made him 6' 1", sort of willowy without being thin. He had thick dark hair which he wore brushed straight back, and longish so that it curled over his ears. He had a mustache that was just as black, and a tuft of black hair showed at the vee of his shirt, which he wore with the top three buttons open. It was a lavender dress shirt. His jeans were stone washed and designer labeled, and his lizard skin cowboy boots were ivory colored and would have been a nice match to Patty's sweater. Except for the mustache his dark face was cleanshaven, with the shadow of a dark beard lurking. His nose was strong and straight. His eyes were dark and moved a lot. If you had told him he was the cat's ass he'd have given you no argument.

"Paul says he was worried about his mom," Patty said and dazzled me with her even smile. "And I want to thank you for looking out for him."

"I wasn't looking out for him," I said. "He does that himself. I was helping him look for you."

She smiled again just as if I'd told her that her hair was looking lovely.

"As you can see, I'm fine. Rich and I just wanted to"-she waved her arms a little-"elope."

Paul said, "Did you get married?"

Patty smiled even more beguilingly.

"Well, not exactly, if you mean all that foolishness with organ music and somebody saying a bunch of words. But we love each other and wanted to get away and be alone."

I was quiet. My size made Rich uncomfortable. I don't know how I knew that, but I knew it. There was something about how he looked at me and shifted a little on the wall. But it wasn't a total setback for him; he still managed to look contemptuous.

"And you didn't think you needed to tell me?" Paul said. "Where you were, or even that you were going?"

"Shame on you, young man," Patty said. "Using that tone with your mother." I could see Paul lower his head a little and shakeit as if a swarm of gnats were bothering him. I shut up.

"It's the tone that this calls for," Paul said. His voice was tight, but it was clear. "I am your son, your only child, I should know where you are.

Not every minute, but if you are making any moves of substance you should tell me. Do you realize what we've been doing to try and find you?"

"Paul, honey, Rich and I needed to get away, not tell anyone, Rich was very clear about that. Weren't you, darling?"

I've never heard anyone call anyone darling without sounding like a fool, except Myrna Loy. Patty wasn't close.

"Your mother and I wanted a kind of a honeymoon," Rich said. He had a great voice. He sounded like William B. Williams. "You're a big boy, we figured she could go off for a bit without you."

"So you went away for a bit and bought a house?" Paul said. He wasn't going to flinch.

Rich shrugged. Patty looked a little confused. "Paulie," she said. "Paulie, did you come all the way here to argue with your mother? Do you care if I'm happy?"

Paul shook his head again and plowed ahead.

"For cash?" Paul said. "Under another name?"

"Jeez," Rich said. "You got some nosy kid here, Patty."

Patty's eyes were bigger than was possible. "No," she said. "No, no."

"Does my mother know what you're running away from?" Paul said. There was a rasp in his 209

voice now. I was perfectly still, near him, and a little behind. I looked at

Rich Beaumont. But I said nothing. This was Paul's, not mine.

"Hey, kid, you got some kind of bad mouth," Beaumont said. "For crissake lighten up. We went off and didn't tell you. So let's not make a big fuck ing deal about it."

"Richard!" Patty said and put the back of her hand against her mouth.

"Do you know?" Paul said.

"Paulie, you stop this. I was glad to see you, but now you're spoiling everything."

"Ma," Paul said. He was leaning forward a little as he talked.

"Listen to me," he said. "Do you know who you're with? Do you know why he doesn't want anyone to know where he is? Do you know why he bought the house under another name? And where he got the money?"

They both spoke at once. Rich said, "Hey-"

And Patty said, "Damn you, Paul, I don't want to know! I'm happy, don't you understand that? I'm happy."

Everyone was quiet then for a moment until Paul said, "Yes, but you're not safe."

The silence rolled in as if from a far place and settled in the room.

Everyone stood still, not knowing what to say. Except me. I knew what I should say, which was nothing. And I kept saying it.

Finally Patty looked at Rich, and he said, "Kid, you got no business coming in here and talking like that. And you wouldn't get away with it if you didn't have this Yahoo with you."

"That may be," Paul said, "but here he is."

The Yahoo smiled charmingly and said nothing. He was musing over the prospect of stung Rich up the chimney flue if the opportunity appeared.

From the sofa where she had settled, Pearl yawned largely. Her jaws opened so wide when she yawned that it ended with a squeak which may have been her jaw hinge. I was never quite sure.

"Paul," Patty said. "Please. Don't do this. I've found someone. Rich cares about me. You don't know what being alone is like."

"The hell I don't," Paul said.

From where I stood I could look into the big round gilded Eagle mirror over the fireplace and see my car parked down the slope of the lawn-to-be.

"What did you mean about safe?" Patty said.

"Are you going to tell her?" Paul said to Rich. "Or am I?"

"I am," Beaumont said. "It's not as bad as it sounds, but I was in business with a guy who turned out to have mob connections, and I took some money he says belongs to him."

"And they want it back," Patty said.

Beaumont nodded.

"Well, just give it to them," Patty said.

Beaumont shook his head.

"Why not?" Patty said. "Tell them you're sorry and give them the money." "And this house?" Beaumont said.

"Yes, certainly, sell it. Tell them you'll make good. You have some money."

"None I haven't stolen," Beaumont said. There was no scornfulness in his voice this time, nor selfregard. It was the voice of someone noticing an ugly thing about himself.

"I don't care. Give it to them. We have each other, we can start over, give them the money back."

Beaumont was silent. Paul looked at me.

"It's not that simple," I said. "They intend to kill him."

Patty put her hand to her mouth again in the same gesture she'd used when

Beaumont said fuck. Patty's reaction range was limited.

"But if he gives the money back…" she said.

Beaumont was looking past her out the sliding doors at the end of the living room, which opened out onto the green and yellow woods. He didn't say anything.

"It's a matter of principle now," I said. "These particular people can't let him get away with it. They have to kill him."

All of us were quiet.

Patty said, "Richard?"

Beaumont nodded.

"He's right," Beaumont said. "It's why we had to come here and hide. It's why I couldn't let you tell anyone at all. Not even your kid."

"Richard," she said, "we better go away then."

"We're all right here," Beaumont said. "No one knows we're here." He looked at us. "Do they?"

"No," I said. "No one followed you?"

"No."

"You're sure?"

"Yes."

"Richard, we can't stay here," Patty said. "They might find you."

"How'd you find us?" Beaumont said.

"A charge purchase from Lenox," I said.

Beaumont looked at Patty. "I told you cash," he said. "No charges."

"What harm? It was for us, like our honeymoon. Just that one time is all,

Richard. I didn't know."

"What harm? For Christ's sake, Patty, they found us." He tossed his chin at

Paul and me. "What if it had been Gerry?"

Who.

Beaumont made a dismissive wave with his hand.

"Is Gerry the one you took the money from?"

"Yeah."

"Richard, let's go somewhere else."

Beaumont started to shake his head and then stopped and turned his gaze slowly toward Patty.

"Why?" he said.

"It's too close. They might find us."

"What's going on, Patty?" Beaumont said. "Why might they find us?"

Patty had both hands pressed against her mouth now. She shook her head soundlessly.

"Ma," Paul said, "if you know something you have to say, this is-" He didn't finish.

Patty kept shaking her head with her hands pressed against her mouth.

"You told somebody," Beaumont said. "Goddamn you, you told somebody."

With her head still down and her hands still pressed, she was able to squeeze out the word "Caitlin."

"Caitlin Martinelli? You told her?"

She nodded and took her hands away. "I was so excited," she said, "about buying our house…" She wanted to say more and she couldn't.

"Who told her brother," I said, "who told Joe."

Beaumont nodded and turned and went out of the room. He came back almost at once wearing one of those fleece-lined cattleman's jackets that you can buy in a catalogue and carrying a blue and red Nike gym bag with a shoulder strap.

"I'm out of here," he said. "If you want to come, Patty, come right now. No packing, just come."

As he turned toward her I could see that he had a white-handled automatic stuck in his belt.

Patty looked at Beaumont and then at Paul, and then at her living room with all its fresh-from-theehowroom-floor furniture.

"I…" she said and stopped. "I don't…"

"Patty, damn you, decide," Beaumont said, moving toward the back door.

In the big mirror over the fireplace I saw a dark blue Buick sedan pull up behind my car on the gravel roadway. Another car, a white Oldsmobile, pulled in right behind it.

"They're here," I said. "Beaumont, take Paul and Patty. Get the hell out of here. Paul, when you get safe, call Hawk."

Eight men got out of the cars. Four from each. One of them had a shotgun.

I knelt by the front window and knocked a diamond pane out with the muzzle of the Browning.

Paul looked at me and then at his mother and didn't say a word. He took her arm and dragged her out through the sliders where Beaumont had already gone.

Outside somebody yelled, "Window to the left of the door!"

I thumbed back the hammer and shot the first guy up the walk in the middle of the chest. He went over backwards and fell on his back. The others dashed for cover behind the cars. Carefully I shot out the tires on each car. Two tires per car, so the spare wouldn't help. I'm a good shot, but

I'm not Annie Oakley. It took six rounds. But it also served to pin them down since they didn't know I wasn't shooting at them. At the first gunshot

Pearl sat straight upright, at the second round she bolted out through the still-open sliders. I opened my mouth to yell and closed it. It wouldn't do any good, a gun-shy dog will run no matter what, and she was probably bet ter off in the woods than she was going to be in here pretty soon.

Everything was quiet for the moment. Beaumont must have kept his car stashed on the rutted track behind the house. I never heard it start up, never saw it leave. For all the outfit outside knew, I was Beaumont, still in the house.