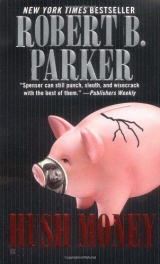

Текст книги "Hush Money"

Автор книги: Robert B. Parker

Жанр:

Крутой детектив

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Robert B Parker

Hush Money

For Joan: all the day and night time.

CHAPTER ONE

Outside my window a mixture of rain and snow was settling into slush on Berkeley Street. I was listening to a spring training game from Florida between the Sox and the Blue Jays. Joe Castiglione and Jerry Trupiano were calling the game and struggling bravely to read all the drop-ins the station had sold. They did as well as anyone could, but Red Barber and Mel Allen would have had trouble with the number of commercials these guys had to slip in. The leisurely pace of baseball had once been made for radio. It allowed the announcers to talk about baseball in perfect consonance with the rhythm of the game. We listened not only to hear what happened but because we liked the music of it. The sound of a late game from the coast, between two teams out of contention on a Sunday afternoon in August, driving home from the beach. The crowd noise was faint in the background, the voices of the play-by-play guys embroidering on a dull game. Now there was little time for baseball talk. There was barely time for play-by-play. And much of the music was gone. Still, it was the sound of spring, and it took some of the chill out of the slush storm.

Just after the fifth inning started, Hawk came into my office with a smallish man in a short haircut, wearing a dark three-piece suit and a red and white polka dot bow tie. His skin was blue black and seemed tight on him. I turned the radio down, but not off.

“Client,” Hawk said.

“Ever hopeful,” I said.

I recognized the small man. His name was Robinson Nevins. He was a professor at the university, the author of at least a dozen books, a frequent guest on television shows, and a nationally known figure in what the press calls The Black Community. Timemagazine had once referred to him as “the Lion of Academe.”

“I’m Robinson Nevins,” he said and put his hand out. I leaned forward and shook it without getting up. “Hawk may be premature in calling me a client. We need to talk a bit first, among other things we ought to find out if we can get along.”

“Whose tab?” I said to Hawk.

“Guarantee half everything I get,” Hawk said.

“That much,” I said.

“I can’t afford very much,” Nevins said.

“Maybe we won’t get along,” I said.

“I am dependent largely on a university salary and, as I’m sure you know, that is not a handsome sum.”

“Depends what sums you’re used to,” I said. “How about the books?”

“The books are well received, and have influence I hope beyond their sales. Their sales are modest. I make some money on the lecture circuit, but far too often I speak because I feel the cause is just rather than the price is right.”

“Don’t you hate when that happens,” I said.

Nevins smiled, but not as if he thought I was funny.

“What would you like to pay me a modest amount to do?” I said.

“I have been denied tenure,” Nevins said.

I stared at him.

“Tenure?” I said.

“Yes. Unjustly.”

“And you want me to look into that?” I said.

“Yes.”

“Tenure,” I said.

“Yes.”

I was silent. Nevins didn’t say anything else. I looked at Hawk.

“You want me to do this?” I said to Hawk.

“Yes.”

I was silent again.

“I understand your reaction,” Nevins said. “I sound churlish to you. And you think that there are causes of greater urgency than whether I get tenure at the university.”

I pointed a finger at Nevins. “Bingo,” I said.

“I know, were I you that would be my reaction. But it is not simply that I am denied tenure and therefore will have to leave. I can find another job. What is at issue here is that I shouldn’t have been denied tenure. I am more qualified than most members of the tenure committee. More qualified than many who have received tenure.”

“You think it’s racial?” I said.

“It would be an easy supposition and one most of us have made correctly in our lives,” Nevins said. “But I am, in fact, not sure that it is.”

“What else?” I said.

“I don’t know. I am something of an anomaly for a black man at the university. I am relatively conservative.”

“What do you teach?”

“American literature.”

“Black perspective?”

“Well, my perspective. I include black writers, but I also include a number of dead white men.”

“Daring,” I said.

“Do you know that we are turning out English Ph.Ds who have never read Milton?”

“I didn’t know that,” I said. “You think you were shot down for being insufficiently correct?”

“Possibly,” Nevins said. “I don’t know. What I know is there was a smear campaign orchestrated by someone, which I believe cost me tenure.”

“You want me to find out who did the smearing?”

“Yes.”

I looked at Hawk again. He nodded.

“Wouldn’t an attorney be more likely to get you your tenure?”

“I am not fighting this because I didn’t get tenure. I’m fighting this because it’s wrong.”

“If you got the tenure decision reversed, would you accept it?”

Nevins smiled at the question.

“You press a person, don’t you,” he said.

“I like to know things,” I said.

“Like how sincere I am about fighting this because it’s wrong.”

“That would be good to know,” I said.

“If I were offered tenure I would have to assess my options. But even if I accepted it, the process was still wrong.”

“What was the thrust of the smear campaign?”

Hawk appeared to be listening to the faintly audible ball game. And he was. If asked, he could give you the score and recap the last inning. He would also be able to tell you everything I said or Nevins said and how we looked when we said it.

“A young man, a graduate student, committed suicide this past semester. It was alleged to be the result of a sexual relationship with me.”

“What was his name?” I said.

“Prentice Lamont.”

“Any truth to it?”

“None.”

I nodded.

“I imagine you’d like that laid to rest as well.”

“Yes.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Okay meaning you’ll do it?”

“Yep.”

Nevins seemed mildly puzzled.

“Like that?”

“Yep.”

“Aren’t you going to ask if I’m gay?”

“Nope.”

“Why not?”

“Don’t care.”

“But,” Nevins frowned, “it might be germane.”

“If it is, I’ll ask,” I said.

Nevins opened his mouth and closed it and sat back in his chair. Then he took a green-covered checkbook out of his inside coat pocket.

“What will you need for a retainer?”

“No need for a retainer,” I said.

“Oh, but I insist. I don’t want favors.”

Hawk was looking out the window at the slush accumulating around the stylishly booted ankles of the young women leaving the insurance companies on their way to lunch.

Without turning around he said, “He doing me the favor, Robinson.”

Nevins was not slow. He looked once at Hawk, and back at me, and nodded to himself. He put the green checkbook back inside his coat and stood.

“Do you need anything else right now?” he said.

“No. I’ll poke around at it, see what develops.”

“And I’ll hear from you?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Will you be involved, Hawk?”

Hawk turned from the window and grinned at Nevins.

“Sure,” he said. “I’ll help him with the hard stuff.”

Nevins put out his hand. “I appreciate your taking this,” he said, “for whomever you’re doing the favor.”

I shook it.

“You need a ride anyplace?” he said to Hawk.

Hawk shook his head. Nevins nodded as if to confirm something in his head, and turned and left. Hawk continued to look out the window. The ball game had moved quietly into the eighth inning. Outside my window it was mostly rain now. Hawk turned away from the window and looked at me without expression.

“Tenure?” I said.

Hawk smiled.

“‘Fraid so,” he said.

CHAPTER TWO

Susan periodically undertook to make my office more homelike, and one of her most successful attempts was the relatively recent introduction of a coffeemaker, coffee canisters, and some color-coordinated mugs. Milk for the coffee then required a small refrigerator, in which I could also keep beer in case of an emergency. The refrigerator, of course, matched the mugs and the canisters and the sugar bowl and milk pitcher. The coffee filters and flatware were in a little drawer in the cabinet that I had built under her direction to hold the refrigerator. Hawk always smiled when he looked at it. Which he was doing now as he made us some coffee.

“Surprised Susan don’t have you color-coordinating your ammunition,” Hawk said.

“Well, she does sort of like the.357,” I said, “because she likes how the lead nose of the bullets contrasts with the stainless steel cylinder.”

“Tasteful in small things,” Hawk said, “tasteful in all things.”

He poured a pot full of water into the coffeemaker and turned the machine on.

“Tell me about Robinson Nevins,” I said.

“Father is Bobby Nevins,” Hawk said.

“The trainer?”

“Un huh.”

Hawk and I both watched the small trickle of coffee that Mr. Coffee was generating very slowly into the pot.

“A watched pot never brews,” I said.

“Yeah it will,” Hawk said.

“You know Bobby Nevins?” I said.

“Yeah.”

“He ever train you?”

“Some,” he said.

“That how you know the kid?”

“Un huh.”

The pot had filled slowly.

“Tole you it would brew,” Hawk said.

“Jeez,” I said. “I was sure I was right.”

Hawk took it from the machine and poured us two cups of coffee.

“You are a domestic fool,” I said when Hawk handed me a cup.

“Ancestors were house slaves,” Hawk said. “It’s in the genes.”

“So how well you know Robinson Nevins?” I said.

“Bobby come closer to bringing me up,” Hawk said, “than anyone else.”

“So you’ve known Robinson all your life.”

“Yes.”

“Well?”

“No, not so much. He was around some.”

“But he came to you when he got in trouble,” I said.

Hawk shook his head.

“Bobby did,” Hawk said.

“He’s still alive?”

“Yeah. Eighty-two now, still healthy, still hangs out at the gym looking for young fighters.”

“So Robinson was born to him late.”

“Yes, only kid. Got divorced when Robinson was pretty small. Wasn’t a good divorce. Don’t know where Robinson’s mother is now.”

“Kid close to his father?”

“Bobby loves that kid,” Hawk said. “Kid grew up mostly with his mother. But Bobby paid the bills and saw the kid when he could and when the kid got to be a professor Bobby was walking around talking like the kid had just become heavyweight champ. You know, I don’t know if Bobby ever even went to school. I’m not sure how much Bobby can read.”

“How about Robinson. He close to Bobby?”

“I think he’s a little embarrassed by his father,” Hawk said. “He’s close to his mamma and his mamma never had much good to say about Bobby.”

I nodded.

“What do you know about his problems?” I said.

“Just what he told you.”

“What do you think?”

“‘Bout the tenure or the suicide or what?”

“Any of the above,” I said.

“Don’t know shit about tenure,” Hawk said. “Kid who died, Prentice Lamont, was a very gay guy. I pretty sure Robinson knew him. Don’t know if Robinson is gay or not.”

“How gay?” I said.

“Activist. Ran a little flier service that outed people.”

“How nice,” I said. “What’s the rumor about him and Robinson?”

“That they had a big affair and Robinson broke it off and the kid killed himself.”

“Love unrequited?”

“That’s the rumor,” Hawk said.

“Bobby Nevins know this rumor?”

“Yeah.”

“What’s he say?”

“He says fix it,” Hawk said. “He wants the kid to get his tenure.”

“Bobby got any money?”

Hawk shook his head. He was holding the coffee mug in both hands, his hips resting against the color-coordinated countertop, the steam from the coffee rising faintly in front of his face.

“So we’re in this for the donut,” I said.

Hawk nodded and smiled. When he smiled he looked like a large black Mona Lisa, if Mona had shaved her head… and had a nineteen-inch bicep… and a 29-inch waist… and very little conscience.

“How’s that work, exactly,” I said. “You take on somebody for no money, and I get to share in the profits?”

“You the detective,” Hawk said.

“True.”

“Whereas,” Hawk said, “I just a simple thug.”

“Also true.”

“And you my friend.”

“Embarrassing, but true.”

“So.” Hawk spread his hands, holding the coffee cup with his right, in a gesture of voilа. “I try to bring you as much business as I can.”

“Like this thing.”

“Exactly,” Hawk said. “And I going to help you with it.”

“Swell,” I said.

“So what we going to do first?” Hawk said.

“Drink some more coffee,” I said.

Hawk nodded. “Tha’s a good start,” he said. “Then what we going to do, bawse?”

“Get you diction lessons,” I said. “I always know when you are really jerking my chain, because you start sounding like Mantan Moreland.”

“Mantan Moreland?”

“I’m kind of proud of coming up with that one myself,” I said. “Where did the Lamont kid do the deed?”

“Had a condo in the South End,” Hawk said. “Did it there.”

“Okay, that’s Boston Homicide. Which means Quirk and Bel-son.”

“So we talk with them first,” Hawk said.

“I’ll talk with them first,” I said. “They’d arrest you.”

“Bigots,” Hawk said.

CHAPTER THREE

I was in Cambridge with Susan. We were cleaning up the backyard behind the house on Linnaean Street where she lived and worked. Pearl the wonder dog was catching some rays on the top step of the back porch while we worked. Since part of what we were cleaning up was left by Pearl, it seemed only right that she be there.

I had dug a large hole in the recently thawed earth in one corner of the yard and into it I was putting shovelfuls of yard waste which Susan, wearing fingerless leather workout gloves, had raked into a number of small piles. One of the things that made Susan so interesting was the fact that she looked like a Jewish princess and worked like a Bulgarian peasant. As far as I knew she had never been tired. I dumped a shovelful of waste into the hole and shoveled a little dirt over it.

“Reminds me of my profession,” I said.

“Cleaning up after?” Susan said.

“Yeah.”

In addition to her workout gloves, Susan had on black tights, a hip-length yellow jacket, and a black Polo baseball cap. In the spirit of cleanup she had put on designer work boots, black leather with silver eyelets, which looked odd, but good, over the tights.

“It’s a good reminder,” Susan said, “of life’s essential messiness.”

“Or Pearl’s.”

“Same thing,” Susan said.

Pearl raised her head slightly at the mention of her name, and then looked slightly annoyed that it was a false alarm. She sighed noisily as she settled her head back down onto her front paws. The sun was bright, and the earth had thawed, but in the shady corners against the fence and under a couple of evergreen shrubs, granular snow lingered like a dirty secret, and lurking inside the sixty-degree temperature was an edge of cold to remind us that it was too early for planting.

When we were done, and I had shoveled the dirt over the waste hole and tamped it down, Susan and I went and sat on the penultimate step, just below Pearl.

“Are you actually going to investigate that tenure case at the university?” Susan said.

“Yes.”

She smiled.

“What,” I said.

“The thought of you rampaging about in the university tenure committee,” Susan said, “is very engaging.”

“Rampaging?” I said. “I can be delicate as a neurosurgeon when it’s called for.”

“Most university tenure committees call for rampaging, I think.”

“I admit to being more comfortable with that approach,” I said.

Moved by an impulse understandable only by another dog, Pearl raised up and began to lap my face. I hunched up and endured it until she decided I’d had enough and switched to Susan.

“How’d you know about the case?” I said.

She was fending Pearl off, so it took her a while to answer. But finally, Pearl-free and makeup still mostly intact, Susan said, “Hawk discussed it with me, before he asked you.”

“He did?” I said.

“He wanted my view on whether he was asking more of you than he should,” Susan said.

“And you answered?”

“I answered that he had the right to ask you for everything and vice versa.”

“What’d he say?”

Susan smiled.

“He agreed,” she said.

I nodded.

“Is Hawk’s friend gay?” Susan said.

“Don’t know,” I said.

“But wouldn’t raging heterosexuality be a useful defense against the allegation that the graduate student killed himself as the result of an affair with Professor Nevins?”

“I guess it would,” I said.

“Did you ask him?”

“No.”

“I understand why you would not, but isn’t it something that needs to be established?”

“Can it be established?” I said. “In my experience it’s not always so clear-cut.”

Susan leaned her elbows on the top step and pressed her head back against Pearl’s rib cage. She thought about my question for a moment while I observed the way in which her posture made her chest press sort of tight against her jacket.

“Are you looking at my boobs?” Susan said.

“I’m a trained investigator,” I said. “I notice everything.”

“Do you make judgments on what you observe?”

“I try not to, but am sometimes forced to.”

“And the boobs?”

“Top drawer,” I said. “What about the question?”

“It’s a good one,” Susan said, “and much more complicated than is generally thought.”

“Then I’ve come to the right place.”

“Yes.” Susan smiled at me. It was a smile that could easily have launched a thousand ships. “Complications R Us.”

She rubbed the back of her head on Pearl for a moment.

“Sexuality is not as fixed as is commonly thought, and the discussion of it has become so political that if you quoted in public what I’m about to say I’d probably deny I said it.”

“Before or after the cock crowed?” I said.

“I didn’t know it crowed,” Susan said.

“Never mind,” I said. “Talk to me about sexuality.”

Susan smiled but didn’t go for the obvious remark.

Instead, she said, “I have treated people who experienced themselves as homosexual at the beginning of therapy and experienced themselves as heterosexual at the end.” Susan was picking her words carefully, even with me. “I have treated people who experienced themselves as heterosexual at the start of therapy and experienced themselves as homosexual at the end.”

“And if you said that in print?”

“A fire storm of outrage.”

“Because you seem to be saying that sexuality can be altered by therapy?”

“I am recounting my experience,” Susan said. “Obviously I have experienced a self-selecting sample: people whose presence in therapy is probably related to either uncertainty about, or dissatisfaction with, their sexuality. It is not always the presenting syndrome, and it is not always what people thought they wanted. Some people come to be ‘cured’ of their homosexuality, only to embrace it by the end of the therapy.”

I nodded. As she concentrated on what she was saying, Susan had stopped rubbing Pearl’s rib cage with her head, and Pearl leaned over and nudged Susan with her nose. Susan reached up and patted her.

“And in the therapeutic community that would be unacceptably incorrect?” I said.

“I don’t know anywhere, but here, that what I’ve said wouldn’t stir up a ruckus.”

“You’ve never minded a ruckus.”

“No,” Susan said. “Actually, I sometimes like ruckuses, but this ruckus would get in the way of my work, and I like my work better even than a ruckus.”

“How about me,” I said. “Do you like me better than a ruckus?”

“You are a ruckus,” Susan said.

CHAPTER FOUR

I talked with Frank Belson in his spiffy new cubicle in the spiffy new police headquarters on Tremont Street in Roxbury.

“Golly,” I said when I sat down.

“Yeah,” Belson said.

“This will knock crime on its ear, won’t it?” I said.

“Right on its ear,” Belson said.

He was built like a rake handle, but harder. And, though I knew for a fact that he shaved twice a day, he always had a blue sheen of beard.

“They issue you a nice new gun when you moved here?”

“I could call informational services,” Belson said. “One of the ladies there be happy to tour you around the new facility.”

“Maybe later,” I said. “What do you know about a suicide named Prentice Lamont?”

“Kid from the university?”

“Yeah.”

“Did a Brody out the window of his apartment. Ten stories.”

“A Brody?”

“Yeah. I heard George Raft say that in an old movie last week,” Belson said. “I liked it. I been saving it up.”

“Why?”

“Why’d he do a Brody?” Belson grinned. “Left a note on his computer. It said, I believe, ‘I can’t go on. There’s someone who will understand why.’”

“What kind of suicide note is that?” I said.

“What, is there some kind of form note?” Belson said. “Pick it up at the stationery store? Fill in the blanks?”

“Did he sign it?”

“On the computer?”

“Well, did he type his name at the end?”

“Yeah.”

“Any thought that maybe he got Brodied?”

“Sure,” Belson said. “You know you always think about that, but there’s nothing to suggest it. And when there isn’t, we like to close the case.”

“Any more on the cause?”

“We were told that he was despondent over the end of a love affair.”

“With whom?”

‘That’s confidential information,“ Belson said.

“Who told you?”

“Also confidential,” Belson said.

He reached into the left-hand file drawer of his desk and ruffled some folders and took one out and put it on his desk.

“That’s why we keep all that information right here in this folder marked confidential. See right there on the front: Con-fid-fucking-dential.”

He put the blue file folder on his desk, and squared it neatly in the center of the green blotter.

“I’m going down the hall to the can,” Belson said. “Be about ten minutes. I don’t want you poking around in this confidential folder on the Lamont case while I’m gone. I particularly don’t want you using that photocopier beside the water cooler.”

“You can count on me, Sergeant.”

Belson got up and walked out of the squad room down the hall. I leaned over the desk and turned the file toward me and opened it. The report was ten pages long. I picked up the file and walked down to the copy machine and made copies. Then I went back to Belson’s cubicle.

When Belson came back the copies were folded the long way and stashed in my inside coat pocket, and the file folder was neatly centered on Belson’s blotter. Belson picked the folder up without comment and put it back in his file drawer.

“Unofficially,” I said, “you got any thoughts about this thing?”

“I’m never unofficial,” Belson said. “When I’m getting laid, I’m getting laid officially.”

“How nice for Lisa,” I said.

Belson grinned.

“I don’t see anything soft in the case,” he said. “The kid was gay, apparently had a love affair with an older man that went sour, and he did the, ah, Brody.”

“You interview the older man?”

“Yep.”

“He admit the affair?”

“Nope. He is a faculty member at the university. I heard he was up for tenure.”

“So he’d have some reason to deny it.”

“I don’t know how they feel on the tenure committee about professors fucking students,” Belson said. “You?”

“I’m guessing it’s considered improper,” I said.

“Maybe,” Belson said.

“You ask?” I said.

Belson dropped his voice.

“The deliberations of the tenure committee are confidential,” he said.

“So they wouldn’t tell you if sex with a student counted for or against tenure?”

“Some of the people I talked to, sex with anything would count,” Belson said.

“But you got no information from the tenure folks.”

“No.”

“And if you yanked their ivy-covered tuchases down here for a talk?” I said.

“Tuchases?”

“You can always tell when a guy’s scoring a Jewess,” I said.

“I thought the plural was tuch-i,” Belson said.

“Shows you’re not scoring a Jewess,” I said. “You didn’t want to shake them up a little?”

“We had no reason to think that the case was anything but an open and shut suicide,” Belson said.

He smiled. “Quirk wanted to run them down here just because they annoyed him,” he said. “But they had the university legal counsel there, and like I say, we had no reason.”

“But it would have been kind of fun,” I said.

Belson smiled but he didn’t comment. Instead he said, “So what’s your interest. You think the suicide’s bogus?”

“Got no opinion,” I said. “I been hired to find out why Robinson Nevins didn’t get tenure.”

“Really?” Belson said.

“He says a malicious smear campaign prevented it, including the allegation that he was the faculty member for whom Lamont did the Brody.”

“See?” Belson said. “I knew you’d like that word. Does he admit it?”

“He denies it.”

Belson shrugged.

“Should be easy enough to prove he had a relationship,” Belson said.

“Harder to prove that he didn’t.”

“Yep.”

I stood up.

“Well, I think your new digs are fabulous.”

“Yeah, me too,” Belson said.

“But it’s a long way from Berkeley Street. What are you going to do when you need help?”

“You’re as close as my nearest phone,” Belson said.

“Well, that must be consoling to you,” I said.

“Consoling,” Belson said.