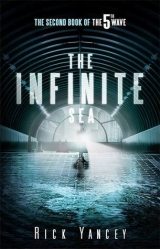

Текст книги "The Infinite Sea"

Автор книги: Rick Yancey

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Rick Yancey.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yancey, Richard.

The infinite sea / Rick Yancey.

pages cm.—(5th wave)

Summary: “Cassie Sullivan and her companions lived through the Others’ four waves of destruction. Now, with the human race nearly exterminated and the 5th Wave rolling across the landscape, they face a choice: brace for winter and hope for Evan Walker’s return, or set out in search of other survivors before the enemy closes in”—Provided by publisher.

[1. Extraterrestrial beings—Fiction. 2. Survival—Fiction. 3. War—Fiction. 4. Science fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.Y19197Inf 2014 [Fic]—dc23 2014022058

ISBN 978-1-101-59901-3

Design by Ryan Thomann. Text set in Sabon.

Cassiopeia photo copyright © iStockphoto.com/Manfred_Konrad.

Version_1

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

THE WHEAT

BOOK ONE

I: THE PROBLEM OF RATS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

II: THE RIPPING

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

III: THE LAST STAR

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

IV: MILLIONS

Chapter 30

V: THE PRICE

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

VI: THE TRIGGER

Chapter 49

BOOK TWO

VII: THE SUM OF ALL THINGS

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

VIII: DUBUQUE

Chapter 84

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For Sandy, guardian of the infinite

My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

My love as deep; the more I give to thee,

The more I have; for both are infinite.

—William Shakespeare

THERE WOULD BE no harvest.

The spring rains woke the dormant tillers, and bright green shoots sprang from the moist earth and rose like sleepers stretching after a long nap. As spring gave way to summer, the bright green stalks darkened, became tan, turned golden brown. The days grew long and hot. Thick towers of swirling black clouds brought rain, and the brown stems glistened in the perpetual twilight that dwelled beneath the canopy. The wheat rose and the ripening heads bent in the prairie wind, a rippling curtain, an endless, undulating sea that stretched to the horizon.

At harvesttime, there was no farmer to pluck a head from the stalk, rub the head between his callused hands, and blow the chaff from the grain. There was no reaper to chew the kernels or feel the delicate skin crack between his teeth. The farmer had died of the plague, and the remnants of his family had fled to the nearest town, where they, too, succumbed, adding their numbers to the billions who perished in the 3rd Wave. The old house built by the farmer’s grandfather was now a deserted island surrounded by an infinite sea of brown. The days grew short and the nights turned cool, and the wheat crackled in the dry wind.

The wheat had survived the hail and lightning of the summer storms, but luck could not deliver it from the cold. By the time the refugees took shelter in the old house, the wheat was dead, killed by the hard fist of a deep frost.

Five men and two women, strangers to one another on the eve of that final growing season, now bound by the unspoken promise that the least of them was greater than the sum of all of them.

The men rotated watches on the porch. During the day the cloudless sky was a polished, brilliant blue and the sun riding low on the horizon painted the dull brown of the wheat a shimmering gold. The nights did not come gently but seemed to slam down angrily upon the Earth, and starlight transformed the golden brown of the wheat to the color of polished silver.

The mechanized world had died. Earthquakes and tsunamis had obliterated the coasts. Plague had consumed billions.

And the men on the porch watched the wheat and wondered what might come next.

Early one afternoon, the man on watch saw the dead sea of grain parting and knew someone was coming, crashing through the wheat toward the old farmhouse. He called to the others inside, and one of the women came out and stood with him on the porch, and together they watched the tall stalks disappearing into the sea of brown as if the Earth itself were sucking them under. Whoever—or whatever—it was could not be seen above the surface of the wheat. The man stepped off the porch. He leveled his rifle at the wheat. He waited in the yard and the woman waited on the porch and the rest waited inside the house, pressing their faces against the windows, and no one spoke. They waited for the curtain of wheat to part.

When it did, a child emerged, and the stillness of the waiting was broken. The woman ran from the porch and shoved the barrel of the rifle down. He’s just a baby. Would you shoot a child? And the man’s face was twisted with indecision and the rage of everything ever taken for granted betrayed. How do we know? he demanded of the woman. How can we be sure of anything anymore? The child stumbled from the wheat and fell. The woman ran to him and scooped him up, pressing the boy’s filthy face against her breast, and the man with the gun stepped in front of her. He’s freezing. We have to get him inside. And the man felt a great pressure inside his chest. He was squeezed between what the world had been and what the world had become, who he was before and who he was now, and the cost of all the unspoken promises weighing on his heart. He’s just a baby. Would you shoot a child? The woman walked past him, up the steps, onto the porch, into the house, and the man bowed his head as if in prayer, then lifted his head as if in supplication. He waited a few minutes to see if anyone else emerged from the wheat, for it seemed incredible to him that a toddler might survive this long, alone and defenseless, with no one to protect him. How could such a thing be possible?

When he stepped inside the parlor of the old farmhouse, he saw the woman holding the child in her lap. She had wrapped a blanket around him and brought him water, little fingers slapped red by the cold wrapped around the cup, and the others had gathered in the room and no one spoke, but they stared at the child with dumbstruck wonder. How could such a thing be? The child whimpered. His eyes skittered from face to face, searching for the familiar, but they were strangers to him as they had been strangers to one another before the world ended. He whined that he was cold and said that his throat hurt. He had a bad owie in his throat.

The woman holding him prodded the child to open his mouth. She saw the inflamed tissue at the back of his mouth, but she did not see the hair-thin wire embedded near the opening of his throat. She could not see the wire or the tiny capsule connected to the wire’s end. She could not know, as she bent over the child to peer into his mouth, that the device inside the child was calibrated to detect the carbon dioxide in her breath.

Our breath the trigger.

Our child the weapon.

The explosion vaporized the old farmhouse instantly.

The wheat took longer. Nothing was left of the farmhouse or the outbuildings or the silo that in every other year had held the abundant harvest. But the dry, lithe stalks consumed by fire turned to ash, and at sunset, a stiff northerly wind swept over the prairie and lifted the ash into the sky and carried it hundreds of miles before the ash came down, a gray and black snow, to settle indifferently on barren ground.

BOOK ONE

THE WORLD IS a clock winding down.

I hear it in the wind’s icy fingers scratching against the window. I smell it in the mildewed carpeting and the rotting wallpaper of the old hotel. And I feel it in Teacup’s chest as she sleeps. The hammering of her heart, the rhythm of her breath, warm in the freezing air, the clock winding down.

Across the room, Cassie Sullivan keeps watch by the window. Moonlight seeps through the tiny crack in the curtains behind her, lighting up the plumes of frozen breath exploding from her mouth. Her little brother sleeps in the bed closest to her, a tiny lump beneath the mounded covers. Window, bed, back again, her head turns like a pendulum swinging. The turning of her head, the rhythm of her breath, like Nugget’s, like Teacup’s, like mine, marking the time of the clock winding down.

I ease out of bed. Teacup moans in her sleep and burrows deeper under the covers. The cold clamps down, squeezing my chest, though I’m fully dressed except for my boots and the parka, which I grab from the foot of the bed. Sullivan watches as I pull on the boots, then when I go to the closet for my rucksack and rifle. I join her by the window. I feel like I should say something before I leave. We might not see each other again.

“So this is it,” she says. Her fair skin glows in the milky light. The spray of freckles seems to float above her nose and cheeks.

I adjust the rifle on my shoulder. “This is it.”

“You know, Dumbo I get. The big ears. And Nugget, because Sam is so small. Teacup, too. Zombie I don’t get so much—Ben won’t say—and I’m guessing Poundcake has something to do with his roly-poly-ness. But why Ringer?”

I sense where this is going. Besides Zombie and her brother, she isn’t sure of anyone anymore. The name Ringer gives her paranoia a nudge. “I’m human.”

“Yeah.” She looks through the crack in the curtains to the parking lot two stories below, shimmering with ice. “Someone else told me that, too. And, like a dummy, I believed him.”

“Not so dumb, given the circumstances.”

“Don’t pretend, Ringer,” she snaps. “I know you don’t believe me about Evan.”

“I believe you. It’s his story that doesn’t make sense.”

I head for the door before she tears into me. You don’t push Cassie Sullivan on the Evan Walker question. I don’t hold it against her. Evan is the little branch growing out of the cliff that she clings to, and the fact that he’s gone makes her hang on even tighter.

Teacup doesn’t make a sound, but I feel her eyes on me; I know she’s awake. I go back to the bed.

“Take me with you,” she whispers.

I shake my head. We’ve been through this a hundred times. “I won’t be gone long. A couple days.”

“Promise?”

No way, Teacup. Promises are the only currency left. They must be spent wisely. Her bottom lip quivers; her eyes mist. “Hey,” I say softly. “What did I tell you about that, soldier?” I resist the impulse to touch her. “What’s the first priority?”

“No bad thoughts,” she answers dutifully.

“Because bad thoughts do what?”

“Make us soft.”

“And what happens if we go soft?”

“We die.”

“And do we want to die?”

She shakes her head. “Not yet.”

I touch her face. Cold cheek, warm tears. Not yet. With no time left on the human clock, this little girl has probably reached middle age. Sullivan and me, we’re old. And Zombie? The ancient of days.

He’s waiting for me in the lobby, wearing a ski jacket over a bright yellow hoodie, both scavenged from the remains inside the hotel: Zombie escaped from Camp Haven wearing only a flimsy pair of scrubs. Beneath his scruffy beard, his face is the telltale scarlet of fever. The bullet wound I gave him, ripped open in his escape from Camp Haven and patched up by our twelve-year-old medic, must be infected. He leans against the counter, pressing his hand against his side and trying to look like everything’s cool.

“I was starting to think you changed your mind,” Zombie says, dark eyes sparkling as if he’s teasing, though that could be the fever.

I shake my head. “Teacup.”

“She’ll be okay.” To reassure me, he releases his killer smile from its cage. Zombie doesn’t fully appreciate the pricelessness of promises or he wouldn’t toss them out so casually.

“It’s not Teacup I’m worried about. You look like shit, Zombie.”

“It’s this weather. Wreaks havoc on my complexion.” A second smile leaps out at the punch line. He leans forward, willing me to answer with my own. “One day, Private Ringer, you’re going to smile at something I say and the world will break in half.”

“I’m not prepared to take on that responsibility.”

He laughs and maybe I hear a rattle deep in his chest. “Here.” He offers me another brochure of the caverns.

“I have one,” I tell him.

“Take this one, too, in case you lose it.”

“I won’t lose it, Zombie.”

“I’m sending Poundcake with you,” he says.

“No, you’re not.”

“I’m in charge. So I am.”

“You need Poundcake here more than I need him out there.”

He nods. He knew I would say no, but he couldn’t resist one last try. “Maybe we should abort,” he says. “I mean, it isn’t that bad here. About a thousand bedbugs, a few hundred rats, and a couple dozen dead bodies, but the view is fantastic . . .” Still joking, still trying to make me smile. He’s looking at the brochure in his hand. Seventy-four degrees year ’round!

“Until we get snowed in or the temperature drops again. The situation is unsustainable, Zombie. We’ve stayed too long already.”

I don’t get it. We’ve talked this to death and now he wants to keep beating the corpse. I wonder about Zombie sometimes.

“We have to chance it, and you know we can’t go in blind,” I go on. “The odds are there’re other survivors hiding in those caves and they may not be ready to throw out the welcome mat, especially if they’ve met any of Sullivan’s Silencers.”

“Or recruits like us,” he adds.

“So I’ll scope it out and be back in a couple of days.”

“I’m holding you to that promise.”

“It wasn’t a promise.”

There’s nothing left to say. There’re a million things left to say. This might be the last time we see each other, and he’s thinking it, too, because he says, “Thank you for saving my life.”

“I put a bullet in your side and now you might die.”

He shakes his head. His eyes sparkle with fever. His lips are gray. Why did they have to name him Zombie? It’s like an omen. The first time I saw him, he was doing knuckle push-ups in the exercise yard, face contorted with anger and pain, blood pooling on the asphalt beneath his fists. Who is that guy? I asked. His name is Zombie. He fought the plague and won, they told me, and I didn’t believe them. Nobody beats the plague. The plague is a death sentence. And Reznik the drill sergeant bending over him, screaming at the top of his lungs, and Zombie in the baggy blue jumpsuit, pushing himself past the point where one more push is impossible. I don’t know why I was surprised when he ordered me to shoot him so he could keep his unkeepable promise to Nugget. When you look death in the eye and death blinks first, nothing seems impossible.

Even mind reading. “I know what you’re thinking,” he says.

“No. You don’t.”

“You’re wondering if you should kiss me good-bye.”

“Why do you do that?” I ask. “Flirt with me.”

He shrugs. His grin is crooked, like his body leaning against the counter.

“It’s normal. Don’t you miss normal?” he asks. Eyes digging deep into mine, always looking for something, I’m never sure what. “You know, drive-thrus and movies on a Saturday night and ice cream sandwiches and checking your Twitter feed?”

I shake my head. “I didn’t Twitter.”

“Facebook?”

I’m getting a little pissed. Sometimes it’s hard for me to imagine how Zombie made it this far. Pining for things we lost is the same as hoping for things that can never be. Both roads dead-end in despair. “It’s not important,” I say. “None of that matters.”

Zombie’s laugh comes from deep in his gut. It bubbles to the surface like the superheated air of a hot spring, and I’m not pissed anymore. I know he’s putting on the charm, and somehow knowing what he’s doing does nothing to blunt the effect. Another reason Zombie’s a little unnerving.

“It’s funny,” he says. “How much we thought all of it did. You know what really matters?” He waits for my answer. I feel as if I’m being set up for a joke, so I don’t say anything. “The tardy bell.”

Now he’s forced me into a corner. I know there’s manipulation going on here, but I feel helpless to stop it. “Tardy bell?”

“Most ordinary sound in the world. And when all of this is done, there’ll be tardy bells again.” He presses the point. Maybe he’s worried I don’t get it. “Think about it! When a tardy bell rings again, normal is back. Kids rushing to class, sitting around bored, waiting for the final bell, and thinking about what they’ll do that night, that weekend, that next fifty years. They’ll be learning like we did about natural disasters and disease and world wars. You know: ‘When the aliens came, seven billion people died,’ and then the bell will ring and everybody will go to lunch and complain about the soggy Tater Tots. Like, ‘Whoa, seven billion people, that’s a lot. That’s sad. Are you going to eat all those Tots?’ That’s normal. That’s what matters.”

So it wasn’t a joke. “Soggy Tater Tots?”

“Okay, fine. None of that makes sense. I’m a moron.”

He smiles. His teeth seem very white surrounded by the scruffy beard, and now, because he suggested it, I think about kissing him and if the stubble on his upper lip would tickle.

I push the thought away. Promises are priceless, and a kiss is a kind of promise, too.

UNDIMMED, THE STARLIGHT sears through the black, coating the highway in pearly white. The dry grass shines; the bare trees shimmer. Except for the wind cutting across the dead land, the world is winter quiet.

I hunker beside a stalled SUV for one last look back at the hotel. A nondescript two-story white rectangle among a cluster of other nondescript white rectangles. Only four miles from the huge hole that used to be Camp Haven, we nicknamed it the Walker Hotel, in honor of the architect of that huge hole. Sullivan told us the hotel was her and Evan’s prearranged rendezvous point. I thought it was too close to the scene of the crime, too difficult to defend, and anyway, Evan Walker was dead: It takes two to rendezvous, I reminded Zombie. I was overruled. If Walker really was one of them, he may have found a way to survive.

“How?” I asked.

“There were escape pods,” Sullivan said.

“So?”

Her eyebrows came together. She took a deep breath. “So . . . he could have escaped in one.”

I looked at her. She looked back. Neither of us said anything. Then Zombie said, “Well, we have to take shelter somewhere, Ringer.” He hadn’t found the brochure for the caverns yet. “And we should give him the benefit of the doubt.”

“The benefit of what doubt?” I asked.

“That he is who he says he is.” Zombie looked at Sullivan, who was still glaring at me. “That he’ll keep his promise.”

“He promised he’d find me,” she explained.

“I saw the cargo plane,” I said. “I didn’t see an escape pod.”

Beneath the freckles, Sullivan was blushing. “Just because you didn’t see one . . .”

I turned to Zombie. “This doesn’t make sense. A being thousands of years more advanced than us turns on its own kind—for what?”

“I wasn’t filled in on the why part,” Zombie said, half smiling.

“His whole story is strange,” I said. “Pure consciousness occupying a human body—if they don’t need bodies, they don’t need a planet.”

“Maybe they need the planet for something else.” Zombie was trying hard.

“Like what? Raising livestock? A vacation getaway?” Something else was bothering me, a nagging little voice that said, Something doesn’t add up. But I couldn’t pin down what that something was. Every time I chased after it, it skittered away.

“There wasn’t time to go into all the details,” Sullivan snapped. “I was sort of focused on rescuing my baby brother from a death camp.”

I let it go. Her head looked like it was about to explode.

I can make out that same head now on my last look back, silhouetted in the second-story window of the hotel, and that’s bad, really bad: She’s an easy target for a sniper. The next Silencer Sullivan encounters might not be as love struck as the first one.

I duck into the thin line of trees that borders the road. Stiff with ice, the autumn ruins crunch beneath my boots. Leaves curled up like fists, trash and human bones scattered by scavengers. The cold wind carries the faint odor of smoke. The world will burn for a hundred years. Fire will consume the things we made from wood and plastic and rubber and cloth, then water and wind and time will chew the stone and steel into dust. How baffling it is that we imagined cities incinerated by alien bombs and death rays when all they needed was Mother Nature and time.

And human bodies, according to Sullivan, despite the fact that, also according to Sullivan, they don’t need bodies.

A virtual existence doesn’t require a physical planet.

When I’d first said that, Sullivan wouldn’t listen and Zombie acted like it didn’t matter. For whatever reason, he said, the bottom line is they want all of us dead. Everything else is just noise.

Maybe. But I don’t think so.

Because of the rats.

I forgot to tell Zombie about the rats.