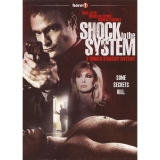

Текст книги "A Shock to the System "

Автор книги: Richard Stevenson

Жанры:

Слеш

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

"There is no peace and love in a lake of fire!" someone boomed—the one who had yelled "Oh my Lord Jesus!" before– but the others quickly shushed him up.

Then, after a little silence, Crockwell said coldly, "Paul, can this be true? That you too subscribe to the illusion that Larry has embraced so emotionally without being cognizant of the consequences?"

"No—no, I think Larry's right," Haig said. "I'm just—gay. I always was and I always will be, and there's nothing wrong with that. The one thing I do know is, I love Larry. When we're together, I just feel—like Larry said—peaceful."

"Peaceful?"

"Well—yeah."

"But how long does this feeling of peace last, Paul? One minute? Five minutes? Do you feel peaceful when you and Larry walk down the street together? When you're with your mother, or when you think of her?"

"No, but that's because—"

"It's because of people like you, Crockwell!" This was Bierly again. "You and your bullshit that you spread around that there's something wrong with gay people. What's sick is you making us sit in those rooms looking at pussy and zapping us when we look at dicks—that is sick. All you ever did for me was make me sick of looking at pussy. I never cared about women's bodies one way

or another until I came here, and now I can't stand the thought of them."

"Why do you think that is, Larry?" This was Crockwell, trying to sound oh-so-cool, but with tremors creeping in. "When you, ah, think about, ah, a woman's genitalia, what comes to mind?"

"I think of you, Crockwell, and I think of those dungeons down the hall—those electrocution chambers that are like something you read about that Saddam Hussein does to people in Iraq. And I'll bet the same thing is true for everybody in this room, isn't it? The only time you ever think about heterosexual sex is when you come here and get strapped into Crockwell’s electric chair. Admit it—isn't it true?"

"No, no, that is definitely not true!" This was a voice I'd heard once before, briefly exclaiming indignantly over Bierly's assertion that nobody knew why anybody turned out gay. With the inflections of what can only be termed a real screamer, this group member again exclaimed, "Because of Dr. Crockwell's procedures, I have finally gotten in touch with my normal sexuality, and I resent your implications in regards to my manhood, Larry! You can just—speak for yourself!"

"Dean, you should be ashamed of yourself," Bierly said. "I mean—suing your own mother and father because they made you gay? I never said anything before, because I never thought you'd go through with it. But that has to be the dumbest, greediest, meanest thing I ever heard of somebody doing to their parents. And Crockwell, you never discouraged him. You—"

"I am not suing them for the cash!" Dean screamed. "It's to set an example for others, and you know it!"

"Larry," Crockwell said, "there's something about Dean's anger with his mother and father that you feel quite strongly about. Would you like to talk about that?"

"No, I'd like to talk about you, Crockwell, you evasive, manipulative piece of ignorant shit! You always throw it back on each of us, but it's you who's everybody's problem. How'd you like a dose of your own medicine? What comes to mind? How do you feel about me challenging you? What if I dragged you down

the hall and strapped you in one of those chairs and zapped you every time you looked at—whatever the fuck turns you on? How do you feel about that, Crockwell? Tell us about your mommy and daddy. What did they do to produce such a cold-blooded, sadistic piece of crap? Huh? Huh?"

"Now, Larry, you are being disruptive." Crockwell was asserting himself as the voice of authority, but it was coming out croaky. "Now, we do have rules to follow as to disruptiveness– rules we all agreed to follow."

"If that's the way Larry feels, I think he should just leave!" This was Mary Mary Quite Contrary again. "The rest of us are here because we want to be here, and to help each other act like real men are supposed to."

"Dean, a real man stands up for himself and stands up for what's right. A real man doesn't turn his life over to some—some Nazi lunatic."

"You are telling me what's a real man, Larry? Now I'm sure I've heard—it—all."

"Those are strong words you're using, Larry," Crockwell said. "You seem to have some awfully strong feelings about me and my role in the group. Perhaps it would be helpful if you examined those feelings."

"Or perhaps it would be helpful if I put your lights out, just put you out of business, Crockwell! A year from now—or even a month from now—everybody in this room with half a brain would thank me."

"I just think maybe Larry ought to leave if he's going to talk like that." This was the one called Gene again. "One of the main reasons we're here is to not let our behavior be ruled by our emotions. If you can't control your emotions, Larry, then maybe you better go. What you're saying sure does get in the way of the things we're trying to accomplish here."

"Gene, what are you trying to accomplish? I remember you said when the group began that you wanted to stop considering yourself a freak. But turning yourself into a gay married liar or a eunuch—isn't that the worst kind of freak of all? Because it's not

really you. What every one of you are doing here is trying to make yourself live a lie. You're all paying Crockwell to turn you into liars. Is that what you want to be? A bunch of lying assholes?"

This caused a largely indecipherable uproar, but it was Crockwell's voice that rose above the others and went on when the hubbub subsided. "That is quite enough, Larry. That is enough vulgarity, and name-calling, and—and—disruption. There are rules here—rules!—and you are breaking the rules. I want you to stop it."

"Fuck you, Crockwell. Fuck you and fuck all your fucking control-freak rules. Paul and I are out of here, and if the rest of you poor fucks want to stay here and let this—this Saddam Hussein torture you—well, I feel sorry for you. I just feel sorry."

"Paul, your mother is going to be so disappointed in you– so very, very disappointed. To reject her, to turn your back on her—"

"Will you please just shut up about my mother!" Haig snapped.

Bierly said, "The only thing that interests you about Phyllis Haig, Crockwell, is that she paid Paul's fees on time."

"Your father's heart would be broken if he knew," Crockwell went on. "Now that your mother needs a normal, whole man in the family more than ever, you plan to tell her your intention is to remain half a man. And that you're proud of it yet! You're going to rub her nose in it!"

"What are you saying?" Haig moaned. "Now that my father is dead, I'm supposed to marry my mother? What are you talking about?"

"Now, Paul, I never said—"

"Larry, you're right about him! You are so, so right about him!"

"Paul, this discussion involving your mother seems to arouse strong feelings on your part. Wouldn't you like to talk about those feelings?"

"Damn it, just you keep my mother out of this. My mother doesn't need a lot of ugly and depressing shit like this. My mother is a wonderful woman, full of life, who always does her damned-

est to look on the bright side of things. She's got joie de vivre. She's like Auntie Mame. To her, life is a banquet and she lives it to the hilt. Yes, she's set in her ways. But I'm used to that. She's not going to change, but why should she? Mother and I got along just fine before she sent me here, and we'll get along just fine after I leave. So, just—just don't bring Mother into this, Dr. Crockwell. Mother has absolutely nothing to do with this! Do you hear me? Do you understand what I'm saying?" Haig had become shrill and sounded as if he was losing control.

"Your mother despises homosexuals," Crockwell said evenly. "That is the hard fact of the matter that you are leaving out."

"Crockwell, you are scum!" This was Bierly. "You are a dangerous, dangerous man—"

"Homosexuals are scum!" Crockwell shot back. "Homosexuals spit on nature and morality. Paul's mother understands that. In his heart, I believe, Paul does too. I'll have to speak with your mother, of course, Paul. I'll have to explain to her that the tough love she exhibited when she brought you to me will have to continue if you choose to leave the group. That it will have to take other forms, and I can advise her about that."

"Dr. Crockwell," Haig said, "I wouldn't do that if I were you. Do not bring my mother into this."

"Oh, it would be a matter of professional responsibility. I would be remiss if I failed to advise your mother, Paul."

"If you turned my mother against me," Haig said, very calmly now, "you would be very sorry you did."

"Oh, I don't see how."

"Don't do it."

"Are you threatening me, Paul?"

"I am telling you. Do not come between Mother and me."

"It's your sexual deviancy that's a barrier between you and your mother's love and approval, Paul. Not I."

"Just stay out of my family, Dr. Crockwell."

"Fortunately for you, in the long run, Paul, I can't do that."

"Well, I'll stop you. I'll just—stop you."

"You'll what?"

"I mean it, Dr. Crockwell. I'll do what I have to, to stop you from coming between Mother and myself."

Now came a long silence. Chairs shifted. Finally, in a voice strained as never before in the session, Crockwell said, "No, you won't stop me, Paul. If I have to, I'll stop you. If you get in the way of my carrying out my duty to uphold moral standards of normalcy, I'll stop you, Paul. I'll just stop you dead in your tracks."

There were gasps and ohs and ahs, and then the tape went silent. I listened to the silence for a minute, then fast-forwarded to the end of the sixty-minute cassette. The remainder was blank. I flipped the tape. The other side was blank in its entirety.

I pocketed the photocopy of the anonymous letter suggesting that Vernon Crockwell had killed Paul Haig, along with my notes on the contents of the tape. I left Al Finnerty's office and went down the stairway and out into the pale sunlight.

I'd left my car up near the house on Crow Street, and that was okay. I didn't need to examine my feelings about where I'd parked my car. Strolling over to Albany Med would give me a chance to air out my brain cells, which had been polluted by my visit of some minutes via the tape with Vernon Crockwell and his victims, or his collaborators, or some unhappy combination of the two. But victims in what? Collaborators in what? Except for the obvious—a quack operating abusively as a mental health professional—I did not yet understand what was happening here.

8

Bierly was still unconscious following his surgery, his condition serious but stable. I got just close enough to him to see that a hospital security guard was posted outside his door. When I asked the charge nurse whether Bierly had had visitors, she said a police detective had come and gone and a friend of Bierly's was out in the waiting area. A man named Steven, she said.

A family of Punjabis occupied the corner of the waiting room near the television monitor, peering with interest at Joan Lunden. Across the room from them, glowering out the window, was a sturdy, well-built man in faded jeans and a flannel shirt. His age, fortyish, suggested the flannel was not hip-kid mosh-wear but was a relic of the butch-gay seventies. He wore work shoes that looked as if they had actually been worked in, and he had a ruddy, angular Anglo or Saxon face and thick auburn hair that curled over his collar. He could have been Lady Chatterley's gamekeeper, Mellors, except for the sweetish cologne that became apparent as I approached him, and the look of hostile suspicion the man gave me as I introduced myself. Mellors, an enduring object of erotic fantasy of mine since the summer between my senior year in high school and freshman year in college, would have been delighted finally to meet me, I'd like to have thought, but this guy clearly wasn't.

"Donald Strachey? No, Larry never mentioned you." He gave my extended hand a brusque tug but didn't get up. I sat down beside him and he shifted uncomfortably.

"The nurse said your name is Steven."

"Yes, it is."

"And you're a friend of Larry's?"

"Yes, I am."

"I guess you're pretty shocked and upset, Steven."

"Of course I am."

"Are you two old friends?"

He stared at me.

I said, "I'm a private detective."

This got a look of mild alarm that was quickly replaced with something that looked calculatedly neutral. He said, "How do you know Larry?"

"On Wednesday he told me he wanted to hire me."

"Hire you? What for?"

"It has to do with the death of Paul Haig. Was Paul a friend of yours too?"

A sheen of perspiration was visible now on his upper lip. His scent was getting stronger too, less perfumy, more Mellors-like. He said, "I didn't know Paul. I mean, not all that well."

"His death was ruled a suicide, but Larry thought Paul was murdered. He never mentioned that to you?" He just stared at me, closemouthed. "It seems odd, Steven, that Larry wouldn't have mentioned it to someone who was close enough to him to visit him in the hospital first thing on the morning after he'd been shot."

This shook something loose. "Well, he did mention that he had some suspicions about Paul's death. But Larry never said anything about hiring a detective or anything like that."

"How long have you known Larry?"

"Not long."

"A year? Six months?"

"About six months."

"Where did you meet?"

He glared. "That's no concern of yours. What right do you have to ask me these questions?" Then he thought of something that made him wince. "Are the police going to question me too?"

"There was one here this morning, a detective by the name of Guy Colson. I guess he missed you. You'd remember him."

"I just got here about twenty minutes ago. I heard on Channel 8 that Larry had been shot, and I drove straight up. There would be no point in me talking to the police. I don't know anything about who shot Larry. Wasn't it probably a robbery or something?"

"It doesn't look that way. Nothing obvious was taken. Why don't you want to talk to the cops?"

"Because—because I have nothing to offer. I have no information." Sweat rings were evident now under his arms. "I have no idea who would want to shoot Larry."

"What about Vernon Crockwell?"

"Oh, no." He blanched—not blushed, blanched—and shook his head three times.

I said, " 'Oh, no, Crockwell would never do such a thing,' or 'Oh, no, it must have been Crockwell who did it'?"

"I have to go," Steven said. He stood up abruptly and strode toward the corridor.

I followed. "What's your last name, Steven, in case anybody has to get in touch?" He said nothing, just turned in the direction of the elevators. "Where do you live?" He marched down the hall in what looked like a barely controlled state of panic. He worked at the elevator down button repeatedly, as if it were a suction pump and his exertions could make the doors open and the car appear. I stood next to him and waited. When a car finally showed up, I stepped inside with him.

An orderly was on board behind a tiny ancient woman in a wheelchair. "What's that smell?" she said. The orderly made a sniff-sniff face but didn't reply. The two of them got off on the third floor. Steven and I rode down to the first. He watched the floor numbers light up and didn't look at me.

As he moved quickly out the main front door and cut right toward the visitors' parking lot, me breathing hard at his side, I said, "Steven, what are you afraid of?" His pace quickened even more. He said nothing.

"Maybe I can help you. Larry trusted me, and you should too."

He looked frantically this way and that, trying, it seemed, to remember where he parked his car.

"Are you in danger, Steven? If you don't want to get mixed up with the police, you can talk to me and what you say can be between us." He spotted his car and made straight for it. "I think Larry would want you to talk to me, Steven. When he regains consciousness, he'll talk to me anyway, so let's get a head start on this thing, whatever it is. Let's make sure you don't get hurt, and that nobody else does."

He shook his head once desperately and said, "You don't want to know." Then he unlocked the door of an old black VW Rabbit with mud spatters on the side, got in, slammed the door and locked it, made the engine cough, backed out, and headed for the exit gate. I might have followed the VW if I'd had my car with me. But it seemed sufficient to note the Rabbit's license number, which had a code not for Albany County but for Greene, the next county down the Hudson Valley.

I hiked down New Scotland Avenue and across Washington Park. The city had spruced up the park's cozy shady glens and ample sunny greenswards for spring strollers and loungers. Rank upon rank of canary-yellow and plum-colored tulips lined the walkways, each tulip no doubt a dues-paying member of the Albany County Democratic Party. In the last election, many of them had probably voted.

At my office on Central, I hiked up the window to let some air in and must out. Another chunk of old caulking fell off the pane, so I ran a couple of feet of duct tape along that edge to prevent the decapitation of any of the winos who had come to regard my entryway as a place of late-evening safety.

My machine, more up-to-date than its surroundings, had recorded three calls. The first said: "Hi, this is Larry Bierly calling Thursday night at nine-fifteen. I was just wondering if you'd made a decision about working on investigating Paul's death. Please let me know. I'm at Whisk 'n' Apron till about eleven. Then

I'll be home, and then I'll be back here about noon tomorrow. I'm eager to hear what you think, and I really hope you'll take the case. Vernon Crockwell should not be allowed to get away with murder. Thanks."

Bierly had been shot just two hours after placing this call. He did not sound apprehensive, as if he had learned anything startling since I'd met him the evening before. I'd checked the machine from home not long before Bierly's call. But even if I'd gotten the message, it was unlikely I would have told him anything that would have prevented his walking out to the farthest reaches of the mall parking lot and being gunned down just after eleven. Nor could I have informed him that I had decided to hire on with him, or not to, for I had made no such decision on Thursday night. And I still hadn't. I needed to know more.

The second call on the machine went like this: "Don." This carried a tone of reprimand and was followed by a breathy pause. "Don, thissus Phyllis Haig. You never got back to me, Don." Another pause, as if she might be expecting my live or recorded voice to respond. "Well, fine then." More heavy breathing. "Don, are you there? Are you gonna pick up?" Now came a couple of sharp bangs and some scratching sounds, as if she had dropped the receiver. Soon she was back. "Hey, are you gonna take the cake—take the case? Or aren't chu? Don, you gotta get that Bierly cocksucker. That fairy has gotta pay. I'll make him pay for taking my Paul away from me. I'll—" The receiver hit something and fell again, but after more fumbling I was left with a click and a dial tone.

The third call was from my other potential client. "This is Vernon Crockwell calling, Donald, at eight-twenty-five a.m. Friday. Please contact me at your earliest convenience. Larry Bierly has been shot and seriously injured, and the police apparently regard me as a potential or actual suspect. They are on their way here to interrogate me now. I don't know which is more harmful to my reputation, Donald, the police being seen entering my office or my being seen at the police station.

"Donald, I've been in touch with my attorney, Norris Jackacky,

and he has repeated to me his opinion that in spite of your misguided and ultimately futile lifestyle you are the most capable private investigator in Albany. You can probably take some satisfaction in knowing that you've got me over a barrel, and I'm in no position to hold your deviant sexuality over you. We can discuss sexuality later, if you prefer. In any case, please call me at my office to discuss this more urgent matter at your earliest convenience. Thank you."

I had a quick flash of Crockwell "over a barrel," where he was "in no position" to hold my deviant sexuality over me. Could he be ... ? No, almost certainly that wasn't it. Arch-homophobes did occasionally turn out to be homosexual psychopaths. There had been at least one gay-bashing congressman caught with a call boy, and countless reactionary men of the cloth who couldn't keep their hands off hitchhikers or altar boys. And of course there had been J. Edgar Hoover railing against the commie-homo menace whenever he wasn't off-duty with Clyde Tolson rhumbaing in a darling cocktail dress at the Stork Club.

But for Crockwell to have devoted his entire professional life to the relentless exorcism of gay men's sexuality while he was secretly gay himself wouldn't have been just sick, it would have been monstrous. Not that some gay men—Roy Cohn, probably Hoover—weren't monstrous. It was always a possibility. As was deeply repressed homosexuality that sometimes surfaced in the form of horrified fascination with gay sex and the urge to stamp it out. But that was getting into realms beyond me—in most cases probably beyond anybody's sure grasp.

What did seem certain, though, was some kind of odd, powerful connection among Crockwell, Haig and Bierly—and possibly "Steven" and others—that went beyond what I knew or had overheard on the tape of Haig's and Bierly's last session with Crockwell's cure-a-fag group. If so, then what was this connection, and was it somehow getting people killed? It was time to learn more about the other members of the therapy group.

9

First I phoned a friend whose business runs credit checks and asked her to find out all she could about Paul Haig's and Larry Bierly's business and personal finances. She said she'd report back to me in a day or two.

Then I called a contact at the Department of Motor Vehicles and learned that the mud-spattered VW Rabbit was registered to Steven St. James, with an address in the town of Schuylers Landing in Greene County. I noted this and retrieved St. James's residential phone number from what used to be called, descriptively, New York Telephone but now is called—as if it were a nasal decongestant—NYNEX.

Fifteen minutes after leaving a message, I got a callback from a psychotherapist friend in Westmere who specialized in actual sexual dysfunction. As I suspected, she was familiar with Crockwell's practice; she had even treated a few of his alumni. I learned that unlike open-ended groups whose members came and went at various times, Crockwell's was a set one-year program that included both group therapy and individualized aversion therapy. He always had three groups going, each meeting once a week at different times. One old group ended and one new group formed every four months. This way, men who had queued up to be de-queered would never have to wait too long to get started. (Lesbians wishing to be un-dyked were referred to a similar program run by a colleague of Crockwell's in Schenectady; my therapist friend, a lesbian, informed me that the

Schenectady program included not only group and aversion therapy but also hairstyling and makeup tips.)

Then I got out the list Bierly had provided me—and whose accuracy Crockwell had, in effect, confirmed—of the ten men in the previous calendar year's therapy group. The first two men on the list were Haig, now deceased, and Bierly, unconscious in the hospital. Two others were known to be dead, Bierly had told me: Gary Moe and Nelson Bowkar had fallen ill with AIDS-related infections soon after the group had concluded in December and both had died in early February, a double suicide. Bierly had heard later that the two had secretly been lovers while in the Crockwell therapy group—it's where they met—and they had remained in the group because nineteen-year-old Bowkar's family had begged him to stay, and twenty-year-old Moe's evangelical church had paid his $8,200 per annum nonrefundable fee to Crockwell, and Moe didn't want the congregation to think its money had been wasted. Bierly said there had been nothing suspicious about the suicide; Bowkar and Moe left anguished, profusely apologetic notes to their families and jumped off the I-90 Hudson River bridge together.

That left six. Grey Oliveira was married, lived in Saratoga, and was described by Bierly as one of the more stable and rational members of the group, but hard to take on account of his sarcasm. Bierly called Roland Stover, of Albany, a guilt-ridden religious zealot and "fucked-up something awful." LeVon Monroe and Walter Tidlow, also of Albany, were best buddies, Bierly said, and he suspected that they were more than that. Eugene Cebulka, of East Greenbush, was a nice guy, Bierly said, and generally sensible and with a good grip on reality; Bierly wasn't sure why he had stayed in the group.

Bierly had described Dean Moody as "a lunatic." Moody had initiated a lawsuit against his parents, Hal and Loretta Moody of Cobleskill, alleging that through their recklessness—Loretta's emotional closeness to her son and Hal's emotional distracted-ness and uninvolvement—they had turned Dean into a wretched homosexual. This one I had read about in the Times Union earlier

in the year, when the Moodys, all three of them, had been scheduled to appear on Montel. Now I was sorry I hadn't tuned in.

Bierly I didn't need to track down, and luckily the others from the therapy group were listed in area phone books. Conveniently, and probably more than that, Monroe and Tidlow shared both a number and an address on Allen Street. Only one group alumnus was at home when I called; Walter Tidlow said his "roommate" LeVon would be home at lunchtime and they would be willing to discuss Crockwell vis a vis Haig vis a vis Bierly if I wanted to drop by. He also offered lunch; I hadn't yet accepted anybody else's offer to foot my expenses, and I happily took Tidlow up on his offer of free food.

I phoned Crockwell at his office and got his machine. Finnerty and Colson were probably going at him. If Crockwell had stuck to his schedule, he'd have been alone in his office Thursday night when Bierly was being shot, and therefore alibiless. Which meant Crockwell was in trouble whether he had shot Bierly or—as now seemed more and more likely to me—not. Crockwell's accustomed method of assassination was subtler. The tape someone in the group had made and sent to the cops showed that Crockwell could lose control. But losing control when provoked was one thing, and premeditated murder (Haig) and attempted murder (Bierly) was far more dire. It was easy, though, for me to keep an open mind on this point. I had next to nothing to close it around.

Not enough time had passed for Steven St. James to get back to Schuylers Landing, so I didn't phone him. Anyway, what else could I say to him? St. James was scared to death of something, and calling him up and making vague ominous noises would only spook him more. I figured I'd drive down there over the weekend. The Hudson Valley in May actually looked the way Church and Cole and the other local romantic painters of the last century had imagined it, dramatic and dreamy, with De Millean sunsets and enormous blue vistas that made people look tiny but lucky to be alive for a wistful little spell in the Empire State.

I almost returned Phyllis Haig's drunken call of the night before, but couldn't quite make myself dial the number. She

would put her foot down and give me a piece of her mind and tell me a thing or two about manners whenever she got hold of me, but that would have to wait.

Tidlow and Monroe shared the top floor of a tidy, well-kept two-family house on South Allen Street. The stairs up to it were carpeted in Astroturf and the inside of the apartment was stuffed with antimacassared Victorian-style reproductions and shelf upon shelf of carefully arranged and recently dusted glass bric-a-brac. It wouldn't have surprised me if Amanda Wingfield had sashayed into view.

Instead, I found two hospitable men in their mid-thirties who had laid a lovely table and served me Campbell's tomato soup, always a way to this man's heart, and a plate of Ritz crackers with butter. This was washed down with Price Chopper cola. It's easy to tut-tut at the cuisine of the lower middle classes, but I had a feeling Tidlow and Monroe could have eaten better if they hadn't each spent $8,200 the previous year on Vernon Crockwell's de-sodomization program. Or maybe they served this food because they liked it. I know I did.

"We saw about Larry getting shot on the TV this morning," Tidlow said, "and we just couldn't believe it. We never knew anybody who got shot, even though it's extremely common nowadays. American society has become so violent."

"What a tragic year it's been for Larry. First Paul commits suicide, and now this horrible incident. Our hearts go out to Larry."

"You don't think Larry shot himself, do you?" Tidlow said.

I said, "He was shot twice, once in the neck and once in the chest."

"Oh, that's right. I guess it would be hard to shoot yourself more than one time. I shouldn't have stumbled on that one. Me, who never misses Murder, She Wrote."

"Did Paul shoot himself?" Monroe asked.

"No," Tidlow said, "that was pills and liquor, like Marilyn."

I nearly asked if Marilyn was another acquaintance of theirs who had died, but caught myself. Tidlow was a balding, pleasant-faced, pale-skinned man who worked as a bookkeeper for the company that owned the Millpond Mall. He said he'd seen Bierly at the mall occasionally—as he had Paul Haig when he was alive—but hadn't spoken with him in recent weeks and had left the mall at eight p.m. on the previous night, three hours before Bierly had been shot.

Monroe was a balding, pleasant-faced black man who was a bookkeeper for the state tax department. He wore a tartan-plaid necktie and matching socks. He told me he was originally from Rome, New York, where he was named after his mother's favorite pop singer, Vaughn Monroe.