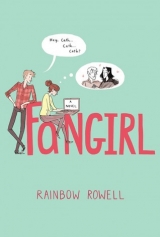

Текст книги "Fangirl"

Автор книги: Rainbow Rowell

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“Nobody knows how it works.”

“What if I don’t even see it coming?”

“I’ll see it coming.”

Cath tried to stop crying, but she’d been crying so long, the crying had taken over, making her breathe in harsh sniffs and jerks.

“If it tries to take you,” Wren said, “I won’t let go.”

A few months later, Cath gave that line to Simon in a scene about Baz’s bloodlust. Wren was still writing with Cath back then, and when she got to the line, she snorted.

“I’m here for you if you go manic,” Wren said. “But you’re on your own if you become a vampire.”

“What good are you anyway,” Cath said. Their dad was home by then. And better. And Cath didn’t feel, for the moment, like her DNA was a trap ready to snap closed on her.

“Apparently, I’m good for something,” Wren said. “You keep stealing all my best lines.”

* * *

Cath thought about texting Wren Friday night before she fell asleep, but she couldn’t think of anything to say.

The Humdrum wasn’t a man at all, or a monster. It was a boy.

Simon stepped closer, perhaps foolishly, wanting to see its face.… He felt the Humdrum’s power whipping around him like dry air, like hot sand, an aching fatigue in the very marrow of Simon’s bones.

The Humdrum—the boy—wore faded denims and a grotty T-shirt, and it probably took Simon far too long to recognize the child as himself. His years-ago self.

“Stop it,” Simon shouted. “Show yourself, you coward. Show yourself!”

The boy just laughed.

—from chapter 23, Simon Snow and the Seventh Oak, copyright © 2010 by Gemma T. Leslie

TWENTY

Her dad and Wren came home on the same day. Saturday.

Her dad was already talking about going back to work—even though his meds were still off, and he still seemed alternately drunk or half-asleep. Cath wondered if he’d stay on them through the weekend.

Maybe it would be okay if he went off his meds. She and Wren were both home now to watch out for him.

With everything that had happened, Cath wasn’t quite sure whether she and Wren were on speaking terms. She decided that they were; it made life easier. But they weren’t on sharing terms—she still hadn’t told Wren anything about Levi. Or about Nick, for that matter. And she didn’t want Wren to start talking about her adventures with their mom. Cath was sure Wren had some mother–daughter Christmas plans.

At first, all Wren wanted to talk about was school. She felt good about her finals, did Cath? And she’d already bought her books for next semester. What classes was Cath taking? Did they have any together?

Cath mostly listened.

“Do you think we should call Grandma?” Wren asked.

“About what?”

“About Dad.”

“Let’s wait and see how he does.”

All their friends from high school were home for Christmas. Wren kept trying to get Cath to go out.

“You go,” Cath would say. “I’ll stay with Dad.”

“I can’t go without you. That would be weird.”

It would seem weird to their high school friends to see Wren without Cath. Their college friends would think it was weird if they showed up anywhere together.

“Somebody should stay with Dad,” Cath said.

“Go, Cath,” their dad said after a few days of this. “I’m not going to lose control sitting here watching Iron Chef.”

Sometimes Cath went.

Sometimes she stayed home and waited up for Wren.

Sometimes Wren didn’t come home at all.

“I don’t want you to see me shit-faced,” Wren explained when she rolled in one morning. “You make me uncomfortable.”

“Oh, I make you uncomfortable,” Cath said. “That’s priceless.”

Their dad went back to work after a week. The next week he started jogging before work, and that’s how Cath knew he was off his meds. Exercise was his most effective self-medication—it’s what he always did when he was trying to take control.

She started coming downstairs every morning when she heard the coffeemaker beeping. To check on him, to see him off. “It’s way too cold to jog outside,” she tried to argue one morning.

Her dad handed her his coffee—decaf—while he laced up his shoes. “It feels good. Come with me.”

He could tell she was trying to look in his eyes, to take his mental temperature, so he took her chin and let her. “I’m fine,” he said gently. “Back on the horse, Cath.”

“What’s the horse?” she sighed, watching him pull on a South High hoodie. “Jogging? Working too much?”

“Living,” he said, a little too loud. “Life is the horse.”

Cath would make him breakfast while he ran—and after he ate and left for work, she’d fall back to sleep on the couch. After a few days of this, it already felt like a routine. Routines were good for her dad, but he needed help sticking to them.

Cath would usually wake up again when Wren came downstairs or came home.

This morning, Wren walked into the house and immediately headed into the kitchen. She came back into the living room with a cold cup of coffee, licking a fork. “Did you make omelettes?”

Cath rubbed her eyes and nodded. “We had leftovers from Los Portales, so I threw them in.” She sat up. “That’s decaf.”

“He’s drinking decaf? That’s good, right?”

“Yeah…”

“Make me an omelette, Cath. You know I suck at it.”

“What will you give me?” Cath asked.

Wren laughed. It’s what they used to say to each other. What will you give me? “What do you want?” Wren asked. “Do you have any chapters you need betaed?”

It was Cath’s turn to say something clever, but she didn’t know what to say. Because she knew that Wren didn’t mean it, about betaing her fic, and because it was pathetic how much Cath wished that she did. What if they spent the rest of Christmas break like that? Crowded around a laptop, writing the beginning of the end of Carry On, Simon together.

“Nah,” Cath said finally. “I’ve got a doctoral student in Rhode Island editing all my stuff. She’s a machine.” Cath stood up and headed for the kitchen. “I’ll make you an omelette; I think we’ve got some canned chili.”

Wren followed. She jumped up onto the counter next to the stove and watched Cath get the milk and eggs from the refrigerator. Cath could crack them one-handed.

Eggs were her thing. Breakfasts, really. She’d learned to make omelettes in junior high, watching YouTube videos. She could do poached eggs, too, and sunny side up. And scrambled, obviously.

Wren was better at dinners. She’d gone through a phase in junior high when everything she made started with French onion soup mix. Meat loaf. Beef Stroganoff. Onion burgers. “All we need is soup mix,” she’d announced. “We can throw all these other spices away.”

“You girls don’t have to cook,” their dad would say.

But it was either cook or hope that he remembered to pick up Happy Meals on the way home from work. (There was still a toy box upstairs packed with hundreds of plastic Happy Meal toys.) Besides, if Cath made breakfast and Wren made dinner, that was at least two meals their dad wouldn’t eat at a gas station.

“QuikTrip isn’t a gas station,” he’d say. “It’s an everything-you-really-need station. And their bathrooms are immaculate.”

Wren leaned over the pan and watched the eggs start to bubble. Cath pushed her back, away from the fire.

“This is the part I always mess up,” Wren said. “Either I burn it on the outside or it’s still raw in the middle.”

“You’re too impatient,” Cath said.

“No, I’m too hungry.” Wren picked up the can opener and spun it around her finger. “Do you think we should call Grandma?”

“Well, tomorrow’s Christmas Eve,” Cath said, “so we should probably call Grandma.”

“You know what I mean.…”

“He seems like he’s doing okay.”

“Yeah…” Wren cranked open the can of chili and handed it to Cath. “But he’s still fragile. Any little thing could throw him off. What’ll happen when we go back to school? When you’re not here to make breakfast? He needs somebody to look out for him.”

Cath watched the eggs. She was biding her time. “We still have to go shopping for Christmas dinner. Do you want turkey? Or we could do lasagna—in Grandma’s honor. Maybe lasagna tomorrow and turkey on Christmas—”

“I won’t be here tomorrow night.” Wren cleared her throat. “That’s when … Laura’s family celebrates Christmas.”

Cath nodded and folded the omelette in half.

“You could come, you know,” Wren said.

Cath snorted. When she glanced up again, Wren looked upset.

“What?” Cath said. “I’m not arguing with you. I assumed you were doing something with her this week.”

Wren clenched her jaw so tight, her cheeks pulsed. “I can’t believe you’re making me do this alone.”

Cath held up the spatula between them. “Making you? I’m not making you do anything. I can’t believe you’re even doing this when you know how much I hate it.”

Wren shoved off the counter, shaking her head. “Oh, you hate everything. You hate change. If I didn’t drag you along behind me, you’d never get anywhere.”

“Well, you’re not dragging me anywhere tomorrow,” Cath said, turning away from the stove. “Or anywhere, from now on. You are hereby released of all responsibility, re: dragging me along.”

Wren folded her arms and tilted her head. The Sanctimonious One. “That’s not what I meant, Cath. I meant … We should be doing this together.”

“Why this? You’re the one who keeps reminding me that we’re two separate people, that we don’t have to do all the same things all the time. So, fine. You can go have a relationship with the parent who abandoned us, and I’ll stay here and take care of the one who picked up the pieces.”

“Jesus Christ”—Wren threw her hands in the air, palms out—“could you stop being so melodramatic? For just five minutes? Please?”

“No.” Cath slashed the air with her spatula. “This isn’t melodrama. This is actual drama. She left us. In the most dramatic way possible. On September eleventh.”

“After September eleventh—”

“Details. She left us. She broke Dad’s heart and maybe his brain, and she left us.”

Wren’s voice dropped. “She feels terrible about it, Cath.”

“Good!” Cath shouted. “So do I!” She took a step closer to her sister. “I’m probably going to be crazy for the rest of my life, thanks to her. I’m going to keep making fucked-up decisions and doing weird things that I don’t even realize are weird. People are going to feel sorry for me, and I won’t ever have any normal relationships—and it’s always going to be because I didn’t have a mother. Always. That’s the ultimate kind of broken. The kind of damage you never recover from. I hope she feels terrible. I hope she never forgives herself.”

“Don’t say that.” Wren’s face was red, and there were tears in her eyes. “I’m not broken.”

There weren’t any tears in Cath’s eyes. “Cracks in your foundation.” She shrugged.

“Fuck that.”

“Do you think I absorbed all the impact? That when Mom left, it hit my side of the car? Fuck that, Wren. She left you, too.”

“But it didn’t break me. Nothing can break me unless I let it.”

“Do you think Dad let it? Do you think he chose to fall apart when she left?”

“Yes!” Wren was shouting now. “And I think he keeps choosing. I think you both do. You’d rather be broken than move on.”

That did it. Now they were both crying, both shouting. Nobody wins until nobody wins, Cath thought. She turned back to the stove; the eggs were starting to smoke. “Dad’s sick, Wren,” she said as calmly as she could manage. She scraped the omelette out of the pan and dropped it onto a plate. “And your omelette’s burnt. And I’d rather be broken than wasted.” She set the plate on the counter. “You can tell Laura to go fuck herself. Like, to infinity and beyond. She doesn’t get to move on with me. Ever.”

Cath walked away before Wren could. She went upstairs and worked on Carry On.

* * *

There was always a Simon Snow marathon on TV on Christmas Eve. Cath and Wren always watched it, and their dad always made microwave popcorn.

They’d gone to Jacobo’s the night before for popcorn and other Christmas supplies. “If they don’t have it at the supermercado,” their dad had said happily, “you don’t really need it.” That’s how they ended up making lasagna with spaghetti noodles, and buying tamales instead of a turkey.

With the movies on, it was easy for Cath not to talk to Wren about anything important—but hard not to talk about the movies themselves.

“Baz’s hair is sick,” Wren said during Simon Snow and the Selkies Four. All the actors had longer hair in this movie. Baz’s black hair was swept up into a slick pompadour that started at his knifepoint widow’s peak.

“I know,” Cath said, “Simon keeps trying to punch him just so he can touch it.”

“Right? The last time Simon swung at Baz, I thought he was gonna brush away an eyelash.”

“Make a wish,” Cath said in her best Simon voice, “you handsome bastard.”

Their dad watched Simon Snow and the Fifth Blade with them, with a notebook on his lap. “I’ve lived with you two for too long,” he said, sketching a big bowl of Gravioli. “I went to see the new X-Men movie with Kelly, and I was convinced the whole time that Professor X and Magneto were in love.”

“Well, obviously,” Wren said.

“Sometimes I think you’re obsessed with Basilton,” Agatha said onscreen, her eyes wide and concerned.

“He’s up to something,” Simon said. “I know it.”

“That girl is worse than Liza Minnelli,” their dad said.

An hour into the movie, just before Simon caught Baz rendezvousing with Agatha in the Veiled Forest, Wren got a text and got up from the couch. Cath decided to use the bathroom, just in case the doorbell was about to ring. Laura wouldn’t do that, right? She wouldn’t come to the door.

Cath stood in the bathroom near the door and heard her dad telling Wren to have a good time.

“I’ll tell Mom you said hi,” Wren said to him.

“That’s probably not necessary,” he said, cheerfully enough. Go, Dad, Cath thought.

After Wren was gone, neither of them talked about her.

They watched one more Simon movie and ate giant pieces of spaghetti-sagna, and her dad realized for the first time that they didn’t have a Christmas tree.

“How did we forget the tree?” he asked, looking at the spot by the window seat where they usually put it.

“There was a lot going on,” Cath said.

“Why couldn’t Santa get out of bed on Christmas?” her dad asked, like he was setting up a joke.

“I don’t know, why?”

“Because he’s North bi-Polar.”

“No,” Cath said, “because the bipolar bears were really bringing him down.”

“Because Rudolph’s nose just seemed too bright.”

“Because the chimneys make him Claus-trophobic.”

“Because—” Her dad laughed. “—the highs and lows were too much for him? On the sled, get it?”

“That’s terrible,” Cath said, laughing. Her dad’s eyes looked bright, but not too bright. She waited for him to go to bed before she went upstairs.

Wren still wasn’t home. Cath tried to write, but closed her laptop after fifteen minutes of staring at a blank screen. She crawled under her blankets and tried not to think about Wren, tried not to picture her in Laura’s new house, with Laura’s new family.

Cath tried not to think of anything at all.

When she cleared her head, she was surprised to find Levi there underneath all the clutter. Levi in gods’ country. Probably having the merriest Christmas of them all. Merry. That was Levi 365 days a year. (On leap years, 366. Levi probably loved leap years. Another day, another girl to kiss.)

It was a little easier to think about him now that Cath knew she’d never have him, that she’d probably never see him again.

She fell asleep thinking about his dirty-blond hair and his overabundant forehead and everything else that she wasn’t quite ready to forget.

* * *

“Since there isn’t a tree,” their dad said, “I put your presents under this photo of us standing next to a Christmas tree in 2005. Do you know that we don’t even have any houseplants? There’s nothing alive in this house but us.”

Cath looked down at the small heap of gifts and laughed. They were drinking eggnog and eating two-day-old pan dulce, sweet bread with powdery pink icing. The pan dulce came from Abel’s bakery. They’d stopped there after the supermercado. Cath had stayed in the car; she figured it wasn’t worth the awkwardness. It’d been months since she stopped returning Abel’s occasional texts, and at least a month since he’d stopped sending them.

“Abel’s grandma hates my hair,” Wren said when she got back into the car. “¡Qué pena! ¡Qué lástima! ¡Niño!”

“Did you get the tres leches cake?” Cath asked.

“They were out.”

“Qué lástima.”

Normally, Cath would have a present from Abel and one from his family under the tree. The pile of presents this year was especially thin. Mostly envelopes.

Cath gave Wren a pair of Ecuadorian mittens that she’d bought outside of the Union. “It’s alpaca,” she said. “Warmer than wool. And hypoallergenic.”

“Thanks,” Wren said, smoothing out the mittens in her lap.

“So I want my gloves back,” Cath said.

Wren gave Cath two T-shirts she’d bought online. They were cute and would probably be flattering, but this was the first time in ten years that Wren hadn’t given her something to do with Simon Snow. It made Cath feel tearful suddenly, and defensive. “Thanks,” she said, folding the shirts back up. “These are really cool.”

iTunes gift certificates from their dad.

Bookstore gift certificates from their grandma.

Aunt Lynn had sent them underwear and socks, just to be funny.

After their dad opened his gifts (everybody gave him clothes), there was still a small, silver box under the Christmas tree photo. Cath reached for it. There was a fancy tag hanging by a burgundy ribbon—Cather, it said in showy, black script. For a second Cath thought it was from Levi. (“Cather,” she could hear him say, everything about his voice smiling.)

She untied the ribbon and opened the box. There was a necklace inside. An emerald, her birthstone. She looked up at Wren and saw a matching pendant hanging from her neck.

Cath dropped the box and stood up, moving quickly, clumsily toward the stairs.

“Cath,” Wren called after her, “let me explain—”

Cath shook her head and ran the rest of the way to her room.

* * *

Cath tried to picture her mom.

The person who had given her this necklace. Wren said she was remarried now and lived in a big house in the suburbs. She had stepkids, too. Grown ones.

In Cath’s head, Laura was still young.

Too young, everyone always said, to have two big girls. That always made their mom smile.

When they were little and their mom and dad would fight, Wren and Cath worried their parents were going to get divorced and split them up, just like in The Parent Trap. “I’ll go with Dad,” Wren would say. “He needs more help.”

Cath would think about living alone with her dad, spacey and wild, or alone with her mom, chilly and impatient. “No,” she said, “I’ll go with Dad. He likes me more than Mom does.”

“He likes both of us more than Mom does,” Wren argued.

“Those can’t be yours,” people would say, “you’re too young to have such grown-up girls.”

“I feel too young,” their mom would reply.

“Then we’ll both stay with Dad,” Cath said.

“That’s not how divorce works, dummy.”

When their mom left without either of them, in a way it was a relief. If Cath had to choose between everyone, she’d choose Wren.

* * *

Their bedroom door didn’t have a lock, so Cath sat against it. But nobody came up the stairs.

She sat on her hands and cried like a little kid.

Too much crying, she thought. Too many kinds. She was tired of being the one who cried.

“You’re the most powerful magician in a hundred ages.” The Humdrum’s face, Simon’s own boyhood face, looked dull and tired. Nothing glinted in its blue eyes.… “Do you think that much power comes without sacrifice? Did you think you could become you without leaving something, without leaving me, behind?”

—from chapter 23, Simon Snow and the Seventh Oak, copyright © 2010 by Gemma T. Leslie

TWENTY-ONE

Their dad got up to jog every morning. Cath woke up when she heard his coffeemaker beep. She’d get up and make him breakfast, then fall back to sleep on the couch until Wren woke up. They’d pass on the staircase without a word.

Sometimes Wren went out. Cath never went with her.

Sometimes Wren didn’t come home. Cath never waited up.

Cath had a lot of nights alone with her dad, but she kept putting off talking to him, really talking to him; she didn’t want to be the thing that made him lose his balance. But she was running out of time.… He was supposed to drive them back to school in three days. Wren was even agitating to go back a day early, on Saturday, so they could “settle in.” (Which was code for “go to lots of frat parties.”)

On Thursday night, Cath made huevos rancheros, and her dad washed the dishes after dinner. He was telling her about a new pitch. Gravioli was going so well, his agency was getting a shot at a sister brand, Frankenbeans. Cath sat on a barstool and listened.

“So I was thinking, maybe this time I just let Kelly pitch his terrible ideas first. Cartoon beans with Frankenstein hair. ‘Monstrously delicious,’ whatever. These people always reject the first thing they hear—”

“Dad, I need to talk to you about something.”

He peeked over his shoulder. “I thought you’d already googled all that period and birds-and-bees stuff.”

“Dad…”

He turned around, suddenly concerned. “Are you pregnant? Are you gay? I’d rather you were gay than pregnant. Unless you’re pregnant. Then we’ll deal. Whatever it is, we’ll deal. Are you pregnant?”

“No,” Cath said.

“Okay…” He leaned back against the sink and began tapping wet fingers against the counter.

“I’m not gay either.”

“What does that leave?”

“Um … school, I guess.”

“You’re having problems in school? I don’t believe that. Are you sure you’re not pregnant?”

“I’m not really having problems.…” Cath said. “I’ve just decided that I’m not going back.”

Her dad looked at her like he was still waiting for her to give a real answer.

“I’m not going back for second semester,” she said.

“Because?”

“Because I don’t want to. Because I don’t like it.”

He wiped his hands on his jeans. “You don’t like it?”

“I don’t belong there.”

He shrugged. “Well, you don’t have to stay there forever.”

“No,” she said. “I mean, UNL is a bad fit for me. I didn’t choose it, Wren did. And it’s fine for Wren, she’s happy, but it’s bad for me. I just … it’s like every day there is still the first day.”

“But Wren is there—”

Cath shook her head. “She doesn’t need me.” Not like you do, Cath just stopped herself from saying.

“What will you do?”

“I’ll live here. Go to school here.”

“At UNO?”

“Yeah.”

“Have you registered?”

Cath hadn’t thought that part through yet. “I will.…”

“You should stick out the year,” he said. “You’ll lose your scholarship.”

“No,” Cath said, “I don’t care about that.”

“Well, I do.”

“That’s not what I meant. I can get loans. I’ll get a job, too.”

“And a car?”

“I guess.…”

Her dad took off his glasses and started cleaning them with his shirt. “You should stick out the year. We’ll look at it again in the spring.”

“No,” she said. “I just…” She rubbed the neck of her T-shirt into her sternum. “I can’t go back there. I hate it. And it’s pointless. And I can do so much more good here.”

He sighed. “I wondered if that’s what this was about.” He put his glasses back on. “Cath, you’re not moving back home to take care of me.”

“That’s not the main reason—but it wouldn’t be a bad thing. You do better when you’re not alone.”

“I agree. And I’ve already talked to your grandmother. It was too much, too soon when you guys both moved out at once. Grandma’s going to check in with me a few times a week. We’re going to eat dinner together. I might even stay with her for a while if things start to look rough again.”

“So you can move back home, but I can’t? I’m only eighteen.”

“Exactly. You’re only eighteen. You’re not going to throw your life away to take care of me.”

“I’m not throwing my life away.” Such as it is, she thought. “I’m trying to think for myself for the first time. I followed Wren to Lincoln, and she doesn’t even want me there. Nobody wants me there.”

“Tell me about it,” he said. “Tell me why you’re so unhappy.”

“It’s just … everything. There are too many people. And I don’t fit in. I don’t know how to be. Nothing that I’m good at is the sort of thing that matters there. Being smart doesn’t matter—and being good with words. And when those things do matter, it’s only because people want something from me. Not because they want me.”

The sympathy in his face was painful. “This doesn’t sound like a decision, Cath. This sounds like giving up.”

“So what? I mean—” Her hands flew up, then fell in her lap. “—so what? It’s not like I get a medal for sticking it out. It’s just school. Who cares where I do it?”

“You think it would be easier if you lived here.”

“Yes.”

“That’s a crappy way to make decisions.”

“Says who? Winston Churchill?”

“What’s wrong with Winston Churchill?” her dad said, sounding mad for the first time since they’d started talking. Good thing she hadn’t said Franklin Roosevelt. Her dad was nuts about the Allied Forces.

“Nothing. Nothing. Just … isn’t giving up allowed sometimes? Isn’t it okay to say, ‘This really hurts, so I’m going to stop trying’?”

“It sets a dangerous precedent.”

“For avoiding pain?”

“For avoiding life.”

Cath rolled her eyes. “Ah. The horse again.’

“You and your sister and the eye-rolling … I always thought you’d grow out of that.” He reached out and took her hand. She started to pull away, but he held tight.

“Cath. Look at me.” She looked up at him reluctantly. His hair was sticking up. And his round, wire-rimmed glasses were crooked on his nose. “There is so much that I’m sorry for, and so much that scares me—”

They both heard the front door open.

Cath waited a second, then pulled her hand away and slipped upstairs.

* * *

“Dad told me,” Wren whispered that night from her bed.

Cath picked up her pillow and left the room. She slept downstairs on the couch. But she didn’t really sleep, because the front door was right there, and she kept imagining someone breaking in.

* * *

Her dad tried to talk to her again the next morning. He was sitting on the couch in his running clothes when she woke up.

Cath wasn’t used to him fighting her like this. Fighting either of them ever, about anything. Even back in junior high, when she and Wren used to stay up too late on school nights, hanging out in the Simon Snow forums—the most their dad would ever say was, “Won’t you guys be tired tomorrow?”

And since they’d come home for break, he hadn’t even mentioned the fact that Wren was staying out all night.

“I don’t want to talk anymore,” Cath said when she woke up and saw him sitting there. She rolled away from him and hugged her pillow.

“Good,” he said. “Don’t talk. Listen. I’ve been thinking about you staying home next semester.…”

“Yeah?” Cath turned her head toward him.

“Yeah.” He found her knee under the blanket and squeezed it. “I know that I’m part of the reason you want to move home. I know that you worry about me, and that I give you lots of reasons to worry about me.…”

She wanted to look away, but his eyes were unshakable sometimes, just like Wren’s.

“Cath, if you’re really worried about me, I’m begging you, go back to school. Because if you drop out because of me, if you lose your scholarship, if you set yourself back—because of me—I won’t be able to live with myself.”

She pushed her face back into the couch.

After a few minutes, the coffeemaker beeped, and she felt him stand up.

When she heard the front door close, she got up to make breakfast.

* * *

She was upstairs, writing, when Wren came up that afternoon to start packing.

Cath didn’t have much to pack or not to pack. All she’d really brought home with her was her computer. For the last few weeks she’d been wearing clothes that she and Wren hadn’t liked well enough to take to college with them.

“You look ridiculous,” Wren said.

“What?”

“That shirt.” It was a Hello Kitty shirt from eighth or ninth grade. Hello Kitty dressed as a superhero. It said SUPER CAT on the back, and Wren had added an H with fabric paint. The shirt was cropped too short to begin with, and it didn’t really fit anymore. Cath pulled it down self-consciously.

“Cath!” her dad shouted from downstairs. “Phone.”

Cath picked up her cell phone and looked at it.

“He must mean the house phone,” Wren said.

“Who calls the house phone?”

“Probably 2005. I think it wants its shirt back.”

“Ha-bloody-ha,” Cath muttered, heading downstairs.

Her dad just shrugged when he handed her the phone.

“Hello?” Cath said.

“Do we want a couch?” someone asked.

“Who is this?”

“It’s Reagan. Who else would it be? Who else would need to get your permission before they brought home a couch?”

“How’d you get this number?”

“It’s on our housing paperwork. I don’t know why I don’t have your cell, I guess I usually don’t have to look very far to find you.”

“I think you’re the first person to call our house phone in years. I didn’t even remember where it was.”

“That’s fascinating, Cath. Do we want a couch?”

“Why would we want a couch?”

“I don’t know. Because my mom is insisting that we need one.”

“Who would sit on it?”

“Exactly. It might have been useful last semester to keep Levi from shedding all over our beds, but that’s not even an issue anymore. And if we have a couch, we’ll literally have to climb over it to get to the door. She’s saying no, Mom.”

“Why isn’t Levi an issue anymore?”

“Because. It’s your room. It’s stupid for you to be hiding in the library all the time. And he and I only have one class together next semester anyway.”

“It doesn’t matter—,” Cath said.

Reagan cut her off: “Don’t be stupid. It does matter. I feel really shitty about what happened. I mean, it’s not my fault you kissed him and that he kissed that idiot blonde, but I shouldn’t have encouraged you. It won’t happen again, ever, with anyone. I’m fucking done with encouragement.”

“It’s okay,” Cath said.

“I know that it’s okay. I’m just saying, that’s the way it’s gonna be. So no to the couch, right? My mom is standing right here, and I don’t think she’ll leave me alone until she hears you say no.”

“No,” Cath said. Then raised her voice: “No to the couch.”

“Fuck, Cath, my eardrum … Mom, you’re pushing me to swear with this stupid furniture.… All right, I’ll see you tomorrow. I’ll probably have an ugly lamp with me and maybe a rug. She’s pathological.”

Cath’s dad was standing in the kitchen watching her. Her dad, who actually was pathological.