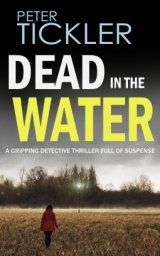

Текст книги "Dead in the Water"

Автор книги: Peter Tickler

Жанры:

Полицейские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Chapter 2

When Mullen arrived at the Meeting Place at 5.30 p.m. on the dot, he immediately sensed that something was different. There were more than the usual number of clients for this time of day and the conversations were muted and secretive. The World Cup had kicked off only the night before and yet no-one seemed to be talking about it. Mullen wasn’t much interested in any case. The patriot inside him wanted England to surprise everyone and win the thing – preferably beating Germany in the process – but the realist told him that this was only marginally more likely than the moon turning out to be made of cheese. He made his way through the throng and greeted his fellow volunteers. Kay and Alex were already hard at work making sandwiches, and the manager Kevin Branston, broad of beam and heavily bearded, homed in on him, clapping him unnecessarily hard on the upper arm.

“Good to see you, Doug. Can you mingle tonight?”

Doug had been asked to mingle every session since Branston had discovered he had a military background. “We need someone who can handle himself in a difficult situation,” he had explained on that occasion, ignoring the fact that Mullen had just told him his expertise had been in communications, not hand-to-hand combat. Mullen’s army career had lasted barely two years, but Branston was now convinced that his usefulness lay primarily in dealing with any nastiness that might suddenly erupt. This became more understandable to Mullen when he looked around at the rest of the volunteers: all of them, with the exception of the stick-thin student Mel, were well past pensionable age.

“See the Brazil game last night?” Mullen asked, keen to make use of the time he had wasted in front of the TV.

Branston ignored the question. “Folks are a bit on edge,” he said. “Chris was fished out of the river a couple of days ago.”

“Chris?” For the briefest moment, Mullen wondered what on earth Branston was talking about. And then all the bells in his head started ringing in unison.

“Shoulder-length blonde hair tied in a ponytail, camouflage clothes, bare feet and sandals?”

“Of course.”

“Two mornings ago. Some jogger fished him out of the water.”

Mullen looked hard at Branston. Did he know it was he who had pulled Chris out of the river? Was Branston giving him a prod to see how he would react? He wouldn’t have put it past him. But Branston’s mind had apparently moved on to other things. His eyes were traversing the room, looking for someone or checking for trouble. “Anyway, keep on your toes, Mullen.” He patted him on the shoulder and then he was off. Mullen watched him wend his way through the scrum of people queuing for their food. He didn’t warm to Branston. Apart from his patronising manner, there was something shifty about him – a man you couldn’t quite pin down or trust. Or was that Mullen’s own paranoia kicking in? He shook himself. It was time to concentrate on the clients.

Suddenly another hand – or rather a finger – jabbed Mullen in the shoulder blade. He spun around, hands raised, ready to attack or defend. Old habits die hard.

“Steady up, matey.” It was DI Dorkin. “Assaulting an officer can get you in a lot of trouble.”

Mullen dropped his hands. “And so can creeping up on people without warning.”

“You’re a regular here are you?”

“I volunteer every Friday.”

“Bit of a coincidence.” Dorkin scratched at his neck, and then pulled at the collar of his tieless white shirt. He was, Mullen reckoned, the sort of man who would never look comfortable in a suit even though he wouldn’t dream of coming to work without one.

“Is that it?” Mullen asked.

“No,” came the reply. “I think we need a little chat.”

* * *

The ‘little chat’ took place in Branston’s office, which Dorkin had established as his centre of operations for the evening. Branston had been banished and a seriously young uniformed PC stood in the corner of the room trying to look more important than he was. Mullen sat down on a plastic green chair with a comfort value of zero and waited. Dorkin undid the buttons of his jacket and dumped himself into Branston’s office chair. He adjusted its height – up, down and then up again – until he was satisfied. He jiggled from side to side, as if settling himself in for the long haul. Then he unleashed a grin.

“So, Mr Mullen. What have you got to say for yourself?”

Mullen shrugged. As questions went, it didn’t exactly demand a reply.

“You see,” Dorkin continued, “there’s something I don’t quite get, Mr Mullen. You come across a dead body in the river. You fish him out. Like a good upright citizen you dial 999. But then, when questioned, you fail to mention the fact that you know him.”

During the time Dorkin had been settling himself into Branston’s chair, Mullen had been thinking hard about this question. He knew that if Dorkin was an even half-competent detective, he was bound to ask something along these lines. But despite this opportunity to prepare an answer, Mullen doubted that it was going to cut much ice with the laughing policeman here.

“I didn’t exactly know him. I’ve only been coming here for six weeks, on Fridays. Chris was just one of a hundred people thronging the place.” He hoped it didn’t sound quite as feeble as he feared.

“But you’ve spoken to him here, right?”

Mullen paused. Was this a fishing expedition? Was Dorkin just casting a line and hoping for a bite?

“Branston definitely thinks you have.” The detective sat very still, watching Mullen as if they were playing ‘Who blinks first?’

Mullen shrugged. He knew he had to say something. “I’ve probably spoken to half the people here. In the sense of passing the time of day, apologising that I don’t have a spare cigarette, or telling them to tone things down. That doesn’t mean I’d recognise them all if I found them floating face-down in the river.”

Dorkin’s eyes narrowed. “I’d have thought that as a private eye you’d be good at remembering faces.”

“I’ve not been doing it long, have I? Still wearing my L plates.” Mullen smiled, trying to laugh off the question, but Dorkin was having none of it.

“Don’t get smart with me, Muggins. I could make life very difficult for you.”

A warning light flashed somewhere in Mullen’s brain. He had once knocked out a squaddie who had teased him about his name. He clenched his hands over his stomach and reined in the impulse to do the same with Dorkin. “Okay, the fact is I didn’t recognise Chris. Maybe you’re right. Maybe I should have. But I didn’t.”

Dorkin leant back in his chair and gave Mullen another of his full frontal grins. He seemed to be pleased with what he had achieved. “As far as I am concerned, Muggins, you can clear off back to work. Just so long as you tell me what it was you and Chris talked about.”

Mullen smiled back, now fully under control. He had an answer, a very credible one. “The World Cup,” he said.

* * *

Across the other side of the city, at pretty much the same moment as Mullen was checking in for his shift at the Meeting Place, Janice Atkinson was waking up on her sofa. She wasn’t used to drinking alcohol in the middle of the day, especially on an empty stomach, and it had made her ridiculously light-headed, and dopey to boot. She was conscious that she had made a bit of a fool of herself with Doug Mullen, so much so that he had downed his pint and exited the pub with indecent haste. She had, briefly, hated him for that. He could at least have bought her a drink. She had paid him enough. As it was, she had had to buy herself a second large glass of white wine and then drink it on her own. She had picked up a newspaper which someone had left on a nearby seat and had tried to concentrate on reading it, but her brain refused to co-operate. A gaunt young man with a body odour problem had sat himself down on the other side of the table without so much as a ‘do you mind’ and attempted to chat her up. As it happened, she had minded, so she drained what was left in her glass and left, feeling very sorry for herself.

Back home, she had lain down on the sofa and fallen asleep, waking only when the grandfather clock chimed five. She went to the toilet – very necessary – and then checked her mobile in the kitchen. A new text message from Paul informed her that he was going out to play squash later, so only wanted a light meal. She snorted, but set about preparing it anyway. At 5.55 p.m. he arrived home in an upbeat mood. They ate in the kitchen with the TV news on in the background. They exchanged pleasantries and actually agreed that the prospect of four weeks of World Cup football dominating the headlines and the TV schedules was just too much to bear thinking about. Afterwards Paul went upstairs to change and gather together his kit. By seven he had left to meet up with his friend Charles Speight.

Or so he said. Janice wasn’t convinced. All this fussing about his gear could have been a pretence. She had never been so gullible as to believe everything that her husband said and recent events had made her even more sceptical. She waited ten minutes while she made herself a coffee – she really did need a clearer head – and then she put in a call to Rachel Speight. Ostensibly this was to ask her if she’d like to meet for lunch the following week, but in reality it was to establish if Charles was indeed playing squash with her husband that evening. He was. Or at least that was clearly what Rachel believed.

Janice double-checked that the front door was locked and slipped the security chain across. The last thing she wanted was for Paul to return unexpectedly. She settled back down at the kitchen table. She had a couple of hours at least to come up with a plan. She laid out several of Mullen’s photographs and studied her husband chatting to, laughing with, touching and even kissing the woman. Becca Baines. She had thought at first that Mullen wasn’t going to give her the bitch’s name. And especially not her address. But he had caved in soon enough when he saw the envelope of money in her hand. He wasn’t so tough after all. Show a man you aren’t going to take any nonsense and you soon discover what he’s made of. Marshmallow in Mullen’s case. Presumably he had been worried she might go round to Wood Farm armed with a rolling pin or piece of lead piping and inflict some serious damage on the fat cow.

That was the thing she most resented: the woman with whom her husband was messing about – she tried not to think of them as actually having sexual intercourse – was fat. In fact, she reckoned Becca must, technically speaking, be obese. But that thought made Janice feel even angrier. What had Becca got that she hadn’t? Janice downed her coffee, imagining it to be a giant-sized gin and tonic, and swore into the silence of the kitchen. The answer to her unspoken question was simple. What Becca had was youth. It was undeniable. She must be ten years younger, maybe fifteen. But she also wobbled like a jelly. Janice told herself that, unlike Becca the Fat, she had looked after herself diligently over the years: a personal trainer; a boutique hair-dresser in Jericho; daily applications of all sorts of creams to revitalise her skin and put off the inevitable onset of ageing; she had even put herself through seaweed wraps on several occasions. She had avoided Botox. That, as far as she was concerned, was going too far.

Janice focused again on the task in hand and picked up one of the photos from the table. She studied it: Becca’s giggling face was close to Paul’s, as if telling him a dirty joke or possibly making an obscene suggestion about what they could be doing up in the hotel room Paul had booked. Janice spat at her rival’s face and watched with pleasure as a gob of saliva hit her full in the eye. If only she could do that to her in person – or worse! Except that deep down she knew that even if she had the opportunity, she would almost certainly bottle out.

She put the photo back in its place on the table. What was she going to do with them? She ought to have confronted Paul as soon as he got home. She should have laid the photographs out on the table so that he saw them as he walked into the room. Instead she had delivered his supper to him like the perfect Stepford wife and chatted to him about trivialities. What was the point of paying out money to get the photos if she wasn’t going to follow it through?

She put her head in her hands and groaned. What on earth was she going to do? Walk out on him with just her pair of matching suitcases? What good would that do her? He’d probably laugh at her, move Becca in and cancel her monthly allowance. Should she change the locks when he was out at work? But how would she stand legally if she did? Paul and his solicitor Nick Newey were as thick as thieves. She would need to find her own solicitor first and get her advice – her advice because the last thing she was going to do was hire a man to represent her. She selected another photo. In this one Paul and Becca were kissing and his hand was touching her bottom. Janice felt the bitter taste of bile rising in her throat and fought it back down. No, she told herself, I will not be beaten. Not by him. Not when he’s the one in the wrong.

She stood up and went through to the small study which in theory they both shared, though Paul preferred to lounge on the sofa while checking his emails and do all his internet stuff in front of the giant TV. She opened the third desk drawer and pulled out a brown envelope. She picked up a rollerball pen in her right hand and wrote – rather slowly since she was left-handed – her husband’s name and work address on it. Out of the same drawer she located a first class stamp and stuck it on. She went back to the kitchen and inserted that single photo into the envelope, which she sealed. She returned the rest of the photos to Mullen’s envelope and hid them in the utility cupboard behind all the cleaning materials. Paul would never find them there. Then she made her way to the front door. There was a mail box at the end of the road and five minutes later the envelope addressed to Paul Atkinson was safely inside it and she was back home.

She went to the fridge, extricated a bottle of white wine – there was always a bottle of white wine chilling in Janice’s fridge – and poured herself a large glass. She would probably regret it later, but she didn’t care. She deserved it. The die was cast. She had crossed the Rubicon. She imagined Paul at work on Monday, opening the envelope, his jaw dropping when he realised what the contents were, his Adam’s apple bobbing crazily in his throat. Or suppose it wasn’t him who opened his post? She had a sudden ghastly thought. Suppose the dragon lady Doreen opened his post for him? Perhaps she should have written ‘confidential’ on the envelope? What would Doreen say or think? She tried to picture the moment as Doreen, all pursed lips and tasteless fashion sense, handed over the offending article to Paul, thumb and forefinger holding it by the corner as if she might infect herself.

Then Janice began to laugh hysterically. It was a great picture.

* * *

Mullen staggered down the seven steps to the pavement and heaved the box unceremoniously into the boot. This one contained a significant part of his worldly goods, though few of them had any financial or emotional value. A small selection of cutlery, three tasteless mugs, two saucepans, a tray, a small LED desk lamp, a tin decorated with a Dickensian Christmas scene (and containing just four tea bags), cling film, refuse bags and so on. The rear section of his tired old Peugeot was already jam-packed with two cases, two other boxes and several plastic bags. He believed in minimal possessions, and it was ridiculous how much clobber he had collected since his return to the UK. There were a few more bags still waiting to be shifted out of his miserable flat, but that would then be that.

“Excuse me.”

Mullen turned and found himself faced by a woman.

Cute! That was his first thought, though he wasn’t stupid enough to say so. She had dark curly hair, a round face, a single mole on her right cheek and grey-green eyes that looked right into his – and maybe beyond. She was, he reckoned, about thirty. Maybe this was his lucky day.

“Are you Doug Mullen?”

“I am.”

“This Doug Mullen?” She held up one of his business cards.

He nodded. He was wondering how she knew to find him here when his card carried only a website, email address and mobile number.

“Janice recommended you,” she said, still giving him the deep-stare treatment. Janice. Whom he had last seen in the Cricketers Arms, misery personified, with the photos of her husband in one hand and an empty glass in the other. To whom he had made his excuses and left for a pressing job that wasn’t pressing at all. In point of fact, there hadn’t been any job, pressing or otherwise, since then, but Mullen was barely admitting that to himself, let alone to the woman who stood in front of him, appraising him. He wondered how many marks out of ten she was giving him.

“I’m Rose Wilby.” She held out her hand. Mullen took it, holding on for slightly longer than was necessary. She glanced at the car. “Are you doing a runner?”

“Moving house.”

“So you’re not doing a bunk before some unhappy husband comes to get you?”

Mullen gave his default shrug. “Somewhere cheaper – and larger.”

“Larger? It can’t be Oxford then. Where on earth is it? Outer Mongolia?”

“Boars Hill.” Mullen watched her eyes widen. Was it surprise or disbelief? Or both? Not that it was a big deal what she thought, he told himself. But not for the first time in his messy life Mullen was telling himself one thing and believing another. The truth was that attractive women never accosted him in the street, and he wanted it to last for a bit longer. “I’m house-sitting,” he said. “For a professor.”

Rose gave a curious smile, one side of her mouth slightly higher than the other, as she assessed his excuse-cum-explanation for the fact that he was moving to Oxford’s poshest postcode.

“It’s ridiculous really. He pays me to live in his large house while he takes a sabbatical with his wife in the States. Mind you, there’s a lot of garden to look after and some DIY he wants me to do as part of the deal, but frankly . . .”

She smiled again, this time as if genuinely amused. Mullen dribbled to a halt.

“Any nice wardrobes to explore?”

Mullen was puzzled. Was she flirting?

“C S Lewis? Narnia?”

Mullen could see he had disappointed her. He was suddenly back at school, standing up in front of the class, having failed some critical test.

Rose persisted. “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. It’s a book. The house is owned by a professor.”

He finally got the reference. “I’ve seen the film.” He had watched it on TV with his niece Florence. He had rather liked it, except for the bit where Father Christmas appeared. That had seemed odd to him.

Mullen could see that having watched the film was clearly not, as far as Rose Wilby was concerned, in the same league as having read the book. “It’s my favourite book ever,” she said. There was a pause as each of them considered the chasm that lay between them. “I know!” Her earnest face brightened. “I’ll lend you my copy, as long as you promise to return it. Everyone should read it.”

“Thank you.” He didn’t know what else he could say.

“It will appeal to the child in you.”

“What makes you think there is a child in me?” He grinned. This was him flirting back.

But it didn’t have the desired effect. The crooked smile on her face faded into invisibility. “You’re a man, aren’t you? And so by definition you’re a little boy at heart.”

“If you say so.”

“Oh I do.”

They stood facing each other for several seconds, this time in an enforced conversational silence as an ambulance tore past, siren blaring.

“I’d ask you in for a coffee,” he said trying to put things right, “but it’s all packed and I really need to get this car moved before the traffic warden comes calling.”

“I need to talk to you about a job.”

“Your husband, is it?”

She laughed. She held up her left hand, showing him her fingers. Not a ring in sight. “What sort of private investigator are you?”

* * *

Professor Thompson’s house was all you might expect of Boars Hill – and more. A sweeping gravel entrance and an honour guard of trees accompanied visitors – in this case Doug Mullen and Rose Wilby – right up to an imposing Edwardian edifice. Rose ran a curious eye over the façade. She looked up to the third storey, where large latticed windows peered out from under the steeply pitched roofs. It was easy to imagine that there might be a wardrobe inside which offered a secret entrance to another world. Not that C.S. Lewis had lived in Boars Hill. She knew that because she had visited his house in Risinghurst. Lewis’s home was an altogether much less imposing structure than this one. In some ways she had found it rather disappointing, not least because so much of the original three acres of garden had long since been sold off for development.

“Do you mind if I have a snoop around?” she asked as soon as he had unlocked the oak front door.

She didn’t wait for his answer, heading straight up the stairs to the bedrooms, where she took in each room like an estate agent assessing a house for a quick valuation. Downstairs again, as Mullen began to bring his boxes and bags in, she admired the sitting room, the dining room, another sitting room and finally the spacious kitchen with walk-in larder.

The professor – or rather, she suspected, the professor’s wife – had left a considerable supply of tinned and dry goods in the larder. She wondered if Mullen was free to raid their supplies as he liked. Returning to the kitchen, she filled and switched on the kettle, located tea bags and mugs and found a fresh pint of milk sitting unopened in the fridge.

Two minutes later they were sitting down in the kitchen at either end of a long oak table.

“Janice was full of praise for you,” she said. It wasn’t entirely true. Janice had said he was very good at tracking her husband, though she had only admitted this after she had got her to promise on the Bible not to reveal this to anyone. But Janice had been much less complimentary about other aspects of Mullen. “Morally unreliable if you ask me,” had been one of her comments. And, “I bet he looks at himself in the mirror every morning.” Which had only caused Rose to wonder whether Janice had made a pass at him and been rebuffed.

“This is a slightly different job from tracking an errant husband,” she continued. “I want you to find out what happened to a friend of mine called Chris.” Her grey-green eyes saw his blue ones blink in surprise.

“They found him floating face down in the River Thames. Bloodstream full of alcohol. Fell in drunk and drowned.” She paused again, wondering if Mullen would admit to knowing Chris. This was a test. Pass or fail. Right or wrong.

“It was me who found him,” Mullen said. He had passed.

“I know.”

“Who told you?”

She nearly said. It wouldn’t matter if he knew. But she didn’t want to spoon feed the man. Make him work for it.

She unzipped her handbag, removed a small white envelope and placed it on the table. “£300 to show my goodwill. Or rather our goodwill. It’s a group effort.”

Mullen didn’t even pick up the envelope. That was a plus mark as far as she was concerned. Instead he said, “You haven’t exactly given me a lot to go on.”

“I only knew Chris after he started coming to our church a couple of months ago. Sunday mornings and Thursday lunchtimes. I liked him. Lots of us did. Good with the old. Good with the young. He rubbed some people in St Mark’s up the wrong way, but I liked him.”

She shivered. It was colder in the house than it was outside. She wished she’d brought a cardigan or jacket.

Mullen rose from his chair. He ran his fingers through what little hair hadn’t been removed by the barber. “So you think his death is suspicious?”

She nodded, though in her head she was saying ‘stupid question.’ Of course she did. Why would she be here otherwise? “Chris didn’t drink,” she said. “He told me he’d been on the wagon for three years. I believed him.” She fixed Mullen with her eyes.

“Why don’t you tell the police all this?”

“I have. But they’ve already come to the conclusion that he relapsed, got drunk and fell in. Pure and simple. A detective came round to the church this morning. Detective Inspector Dorkin according to his ID. Said they weren’t likely to spend too much time on an open-and-shut case like this.”

Mullen, who had moved across to the sink, twisted his head round and nodded. She got the sense that he was getting interested finally, but not (curiously) so much in the envelope of cash on the table or indeed in her – though he had run an appraising pair of eyes up and down her in the Iffley Road – but in Chris. She wondered why.

“Chris is a nobody as far as they are concerned,” she continued. “Why waste valuable police resources on a nobody?”

Mullen nodded again, like one of those ridiculous dogs that drivers sometimes put in the back window of their cars. She looked at her watch. “So are you taking the case, or what?” It was time for Mullen to make a decision.

He opened his mouth, but said nothing. She could see the uncertainty in his face. Was he thinking of a polite way to say ‘No’?

“I appreciate it’s a long shot,” she said, “so my colleagues and I will not expect you to hand back the £300 if you fail in your assignment.”

“That’s kind.”

“Is that a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’?”

“Yes.”

“In that case, I suggest you come to church tomorrow and meet people who knew Chris. I’ve written the details on the back of the envelope.”

With that, Rose Wilby hoisted her bag over her shoulder and made her exit.