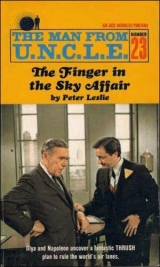

Текст книги "The Finger in the Sky Affair"

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

Chapter 7 – The ray on the hill-top

"It may not be significant, Napoleon," Illya was saying, "but Sherry and I have been checking various things in the T.C.A. records here—and one thing emerges right away: all three of the crashes took place when the planes approached from the southwest; when the runway was being used in the direction from Cannes towards Nice."

"How many runways are there?"

"Only the one—that's the point, you see. Most of the airport is on reclaimed land, and the main runway runs parallel with the coast and the motor road...They keep on extending it every year—to take bigger and faster planes, I suppose—but it just spreads further along the coast, never further out to sea. And it can still only be used from southwest to northeast, or from northeast to southwest."

"And you say all three crashes took place when it was being used from southwest to northeast?"

"Yes. It could be only coincidence: they use the runway much more in that direction than in the other. But they do use it the other way sometimes—especially when there's a mistral blowing."

"Why's that?"

"The mistral comes from the west," Sheridan Rogers answered. "It's very gusty here when it blows—and it blows like the devil, too! Any plane landing from the southwest would have the mistral as a tail wind, so naturally they bring them in the other way. The same goes for take-off."

"Do they use the same runway for landing and take-off?"

"Yes, they do."

"What do you deduce from these facts, then?" Solo asked, turning towards Illya with a smile. "Mr. Kuryakin, you have the floor..."

"Since there is no record of any mishaps when planes land from northeast to southwest, but there were three bad crashes when T.C.A. aircraft came in from the other direction, I go out on a limb and say..." Illya paused. "I say that, since the Murchison-Spears gear proved to be in A-one condition afterwards, then THRUSH—or someone—must be using some kind of device to mess it up only temporarily—and I say further, Napoleon, that this can only be used successfully if the plane approaches from the west."

Solo nodded. "As far as the temporary bit is concerned, that's very much what old man Plant thought," he said. "Any further comments?"

"Yes. Since the device, whatever it is, appears to be in a sense dependent on direction, one is forced to consider the possibility of some sort of beam or ray."

"Yeah. That's what I figured...You mean something actually sited on the west side of the airport, so it can only be used if the ships come in from that side?"

"Exactly—and this implies it must be fairly short-range, too. I should be inclined to suggest something aimed or beamed straight at the plane as it glides in towards the runway over the sea...probably one of the many hilltop villages just behind the coastal strip."

"Or from a boat, maybe?"

Kuryakin shook his head. "We checked that. It would have to be moored or anchored, and there's no record of any such ship—besides, the fisherman from Cagnes, the water-ski schools, the speedboat owners would all notice it: it's a very busy piece of ocean, just there!"

"Okay, no boat. So what about your hilltop villages...?"

"Well, there's Mougins, Biot, Vallauris, La Colle, St.-Paul-de-Vence, Gatti�res, Haut-de-Cagnes—all of them look down on the flight path from the hills dotting the country between the mountains and the sea. You can stand on the ramparts and look down and see the planes silver against the blue sea as they glide in."

"Very poetic...but where do we start looking?"

The Russian smiled, spreading his arms in a gesture of indecision. "It seems to me," he said, pushing the tow-colored hair out of his eyes, "that there's only one possible lead for us to take."

"And that is?"

"To follow up every conceivable angle on the social life of T.C.A. staff based here in Nice. Watch and listen; get to know them; find out how they—how do you say?—tick...Because members of THRUSH must have infiltrated the organization somewhere, and if we can get on to them —"

"You mean once we locate which of the personnel belong to THRUSH, we can tail them and at least get a start geographically?"

"Exactly. It would provide a starting point. After all, we cannot very well knock on every door between here and Cannes and ask: 'Excuse me, do you happen to have a secret ray in the parlor?', can we!"

They were sitting over coffee and brandy on the terrace of a waterfront restaurant at Villefranche. Helga Grossbreitner still kept an apartment somewhere near Nice and she had gone to check that everything was in order there. The other three had decided to hold their council of war in as agreeable a locale as possible. Violet sea water lapped at the piles of the balcony on which they sat and fragmented the reflections from the windows of the customs house on the far side of the harbor. Out in the bay, someone was having a party on one of the big steam yachts. The sound of laughter and music drifted across to mingle with the footsteps and voices of the holidaymakers thronging around them. Farther out, two American cruisers dressed overall added their complement of light to the garland of lamos outlining the whole inlet from Villefranche to Cap Ferrat. Above, the headlights of cars traversing the Basse Corniche, the Moyenne Corniche and the Grande Corniche threaded their way between the brightly illuminated villas rising tier upon tier into the velvet sky. A breath of warm air stirred the purple bougainvillea draping the balustrade by their table.

"I entirely agree with your suggestion, Illya," Solo said as he called for the bill. "As it happens it works in well with an arrangement I've already made. I thought we ought to have a look at the murdered stewardess' apartment—not the one she was sharing with you, my dear; her own place by the Avenue Malausséna—just in case. Miss Grossbreitner has arranged to get the key from T.C.A. and she's meeting me there tomorrow morning. I'd be most grateful if you could join us, Miss Rogers."

Still profoundly shocked by the killing of her friend, Sherry nodded a pale face. "Naturally, if there's anything I can do..."

"Bless you. I don't for a moment imagine we'll find anything significant. But your help will be invaluable in case we do."

A few minutes later Solo said good night and took a cab back to the airport, where he had a rendezvous with T.C.A.'s Technical Director for France. They were to go over the mechanics of the Murchison-Spears equipment—with which Illya was already familiar—and the various safety devices incorporated in the airline's Tridents. Kuryakin and the girl wandered for a few minutes among the steep stone staircases which served as streets between the old houses perched 1,300 feet above the sea, and drove back to Nice along the Moyenne Corniche.

For a long time the girl was silent. Then at last she turned in her seat. "Illya," she said, "do you honestly think you and your friend will be able to clear up all this...this mess?"

"What—the way the crashes were engineered, you mean?"

"Everything...Deliberate sabotage, murders, innocent people dying because a plane crash is to some stock-manipulator's advantage...it's horrible. And then those poor people slaughtered in America...and someone trying to run your friend down in a car...It makes me feel sick."

"It is not a pretty business, I am afraid."

"And what's your business, Illya? I know you and your friend are some kind of investigators—are you G-men or members of the—what is it?—the C.I.A.?"

"Those are United States bodies, Sherry. We work for something like that—but it is an international organization."

"You mean the U.N.?"

"Well—something like that. Let's leave it there...As to whether we can succeed in clearing up the problem, in stopping the crashes and the other deaths: I think we can. Provided T.C.A. itself has not become a THRUSH Satrap, that is..."

"Illya—you have mentioned that word several times: THRUSH. Just what or who is THRUSH?...And what, for pete's sake, is a Satrap?"

The Russian pulled the Peugeot into the side of the wide road. They had just turned a corner and now the lights of Nice lay spread out before them—a measureless tide of bright pinpoints surging against the dark bulk of the hills, heaving itself into groups and clusters and twinkling constellations, spreading almost as far as the eye could see in a corruscating flood.

"Oh," the girl breathed, "isn't it beautiful? I never tire of seeing Nice from this viewpoint."

"It is one of the classic sights," Illya agreed. He turned and took the girl's two hands in his own. "You ask me what is THRUSH," he said. "It is difficult to answer you truthfully—for who knows what THRUSH is? It is an organization, a way of existence, a dedication to evil...it is almost a nation, although you will not find its name on any maps. And yet, again, if you looked at a globe, there would hardly be a country you could touch which was not in some way or another under its influence."

"But who runs this...organization?" Sherry asked practically.

"It is directed by a Council—a collection of industrialists, scientists and intellectuals who see themselves as superbeings whose mission is to rule over others. Each of them is a tremendously powerful individual in his own right in the ordinary world; each has an important cover position—but all of them owe their allegiance only to THRUSH."

"It sounds tremendously sinister. What does THRUSH do, though?"

"Under the direction of the Council it infiltrates, seduces, corrupts, perverts, dominates and finally takes over...anything. An industrial organization, a chain of stores, a college, a manufacturing complex, a radio station, an army even. And, once taken over, the system dominated continues to all intents and purposes to function as before—outwardly. Only now its whole purpose is to serve the aims of THRUSH...And these concealed outposts, as it were, of the supranation called THRUSH are termed Satraps."

"But how does the organization take over these...things, places, people?"

"As I said—infiltration of key personnel, bribery, blackmail, murder, maneuvering the markets (that's what they are trying to do with T.C.A., you see). You name it, they'll do it. Nothing is too rough for them."

"You said the—Satraps?—the Satraps outwardly carried on 'business as usual', but that really they only served the aims of THRUSH?"

"I did."

"Well—what are the aims of THRUSH, Illya?"

"THRUSH has a single purpose, Sherry. It's not for hire. It may appear at times to favor one nation as against another—but strictly for its own reasons. However limited a THRUSH objective may appear to be, however much it may seem to be an operation for financial reward, say—you may depend on it that in some way that operation advances the Cause."

"And that is?"

Kuryakin sighed. "THRUSH's purpose," he said, "is to dominate the earth..."

"And you and your friend—your organization, that is—try to stop them? You ferret out the Satraps, wherever you find them and...destroy them?"

The Russian turned the ignition key and started the motor. He gestured at the panorama beyond the windshield. Below the road the glittering sea-front instigated a chain reaction of street lighting that stretched in a brilliant and dwindling necklace the whole twelve miles around the bay to Cap d'Antibes. "Look at the lights," he said soberly. "Who knows how many hundreds of thousands of people are taking their pleasure, innocent and not so innocent, behind those lights...and behind other lamps just like them all over the world?"

"There are people—let us say—who are trying to put those lights out. We are trying our best to keep them blazing..."

Chapter 8 – A missed appointment—another surprise

Andrea Bergen's apartment was in a small new block not far from the main railway station in Nice. Illya parked the rented 404 on the pavement between two of the plane trees which shaded the quiet avenue and went upstairs with Solo. The place was on the third floor—a large studio room with kitchen and bathroom. It was at the back of the building, the least expensive position, they guessed, facing the rear of a supermarket across a marshaling yard full of trucks carrying imported Italian cars. The police had been quite cooperative about letting them have the keys—though dubious about the chances of their finding anything.

"I must emphasize," Solo had said to the superintendent, "that we are not in any way attempting to go over your ground a second time; nor, indeed, to cast any reflections on the efficient work of your department—professionally speaking, we are not interested in the murder."

"Thank you, Monsieur Solo. It is a crime we appear far short of solving, however. Nobody has come forward—and nobody recollects seeing the short, dark man you described as being near the murdered lady."

"I didn't think they would. It was only a longshot—and anyway the man may be perfectly innocent: my colleague seeing him twice that afternoon may be entirely a coincidence."

"I should doubt that, Monsieur. To professionals such as yourself, the man intent upon doing wrong appears almost to cast an aura, so that his presence and intentions virtually declare themselves. I have every faith in your—what do you say?—eighth sense."

"You flatter us, Monsieur: it is only the sixth sense!"

"Ah. Perhaps justly, my countrymen are celebrated for their courtesy, Monsieur Solo...However, to return to our muttons, as you Americans say—you will hope, then, to discover some things bearing on the airplane crash in which Mademoiselle Bergen was injured?"

"I very much doubt it—but I feel we have to try."

"You will find, I am afraid, no diaries with carefully reasoned résumés of Mademoiselle Bergen's recollections of the incident—for she came here only for a half hour, having been discharged from the hospital, before leaving to share an apartment with a friend."

"Miss Rogers. Yes, we do know that. In fact, Miss Rogers is to meet us at Miss Bergen's apartment to see if she can remember anything the murdered girl said in that half hour—or whether the place reminds her of anything that may be of interest or of use in our inquiry."

"So. Well, I wish you luck, gentlemen, in your quest with the charming Mademoiselle Rogers..."

But the charming Mademoiselle Rogers seemed singularly reluctant to keep her appointment. "What time did Sherry tell you she'd be here?" Solo asked Illya when they had been examining the place for twenty-five minutes—and had found nothing.

"Ten o'clock. The time we arranged to get here."

"Well, that's very odd. We weren't late, so she couldn't have come and gone. When did you last see her, Illya?"

"Last night, of course. We went for a little drive after you left. We had a look at Eze village. And then I drove her home."

"Where did you leave her?"

"Outside her flat, of course," the Russian said, coloring slightly. "In the Rue Masséna."

"All right, all right," Solo said, smiling. "Don't get all Slavic on me. I just thought if you had happened to stay for breakfast, it would —"

"There was nothing like that at all," Illya said stiffly—adding, with a (for him) rare flash of sarcasm: "You forget, Napoleon; I am not the chief enforcement officer!"

"Touché!" The woman's voice drawled sleepily from the door as Solo burst into laughter. Helga Grossbreitner was standing there, leaning against the doorpost. She was wearing a white linen suit with a huge-brimmed hat in lacy black straw—and she looked cool, and infinitely attractive. "Sorry I'm a few minutes late," she added, "but I came on in as the door was open...to hear my virtue—at least by implication—being impugned!"

"Come on in," Solo grinned. "Don't mind my friend: he's just a little jealous."

"Good morning, Helga," Illya said. "Do forgive me. Really, I did not in any way mean —"

"Oh, for heaven's sake!" the girl interrupted. "Don't give it a thought; we're all grown up here. If I don't mind the night porter at a man's hotel seeing me come in without luggage at one A.M., why should I object to good-humored remarks from his friend?" She paused and looked across at Solo speculatively, adding in her throatiest voice: "When are you going to ask me to dinner again, Solo?"

"Tonight," the agent replied promptly. "We're agreed that we should follow up the social life of your employees, and there's a party of them going up to Haut-des-Cagnes. I think we could do worse than tag along. We'll make up a foursome...you do know Sherry Rogers?"

"But of course. Very well. She was already on the staff at the airport when I was working here."

"Good. Which brings me to another point—the one we had been discussing when you came in: Sherry was due here at ten o'clock and now it's twenty-five to eleven. You haven't seen her?"

"I'm afraid not. I shouldn't worry though. She works in Liaison now, doesn't she? There may easily have been some panic at the aéroport."

"I suppose so. There must be plenty of alarms and excursions in your game, apart from crashes—late arrivals, reroutings, diversions and so on..."

"You're telling me!" the girl said. "Can I help in any way?"

"You can try, if you would. All we wanted to ask Sherry was to keep an eye open for anything in this apartment that she thought might throw a light—however faint—on the crash Andrea Bergen was injured in."

"But of course. Have you found anything at all yet?"

Solo and Illya admitted that they hadn't. Nor, despite the able and willing assistance of Helga, were they able to discover a single thing out of the ordinary in the apartment. Clothes, cosmetics and shoes were all neatly in place; the small kitchen held a collection of canned goods in a refrigerator, as befitted the home of a girl whose business took her away several days a week; household bills and bank statements were neatly docketed in a bureau; a bundle of unexceptional letters from a Second Officer in Swissair lived under the sachets in a handkerchief drawer. By twelve thirty, they had to confess that the apartment would yield nothing.

"I shall leave you, then," Helga said, approaching close to Solo and picking a small piece of thread from his lapel with a gloved hand. "Tonight we meet at what time?"

"Let's say seven thirty, okay?"

"Fine," Illya said. "Unless something's happened that makes it too early for Sherry. I'll have to check her apartment and the T.C.A. office to find out what's happened. I can't think what's become of her..."

But the apartment on the Rue Masséna was empty and the T.C.A. bureau at the airport had heard nothing from Sherry Rogers since she went off duty at six thirty P.M. the previous day.

"She's not due on again till tomorrow morning at eight," the pretty, plump girl Illya had spoken too when first he came to the airport volunteered. " I shouldn't worry if I were you. She may have gone off for the day, you know."

"She may, certainly," Illya said to Solo afterwards. "And admittedly I don't know her well—but such behaviour would seem unlike what I have come to expect from her, you know. She definitely said she would see me at Bergen's place today."

"Well, we'll see what happens when it's time for her to show for her next duty," Solo said reasonably. "If she's not here then, you can really start to worry...in the meantime, let's just go over what we know about these automatic landing systems, okay?"

T.C.A.'s Technical Director for France saw them in his office—a small room overlooking the apron from one of the long, low buildings enclosing the company's maintenance unit at Nice. He was a slight man, with smooth dark hair and a clipped moustache, beneath which a long-stemmed pipe with a silver mouthpiece projected. For the whole time they were there, the pipe never left his mouth: it seemed jammed between his teeth, hardly moving except to wag up and down when the exigencies of the language required these to shift their position. Unlike Waverly, however, the owner of this pipe was an active smoker—obscured for much of the time that he spoke by dense clouds of tobacco fumes and surrounded by small ashtrays on which the piles of burned matches gradually mounted.

"Well, chaps," he began, "you both know the general drift now. What's the program for today? Want me to fill you in on the M-S gear?"

"Yes—if you could recap briefly, that would be a help," Solo said. "Then perhaps a few words on the implications vis-à-vis the crashes."

"Wilco," the Technical Director said. He knocked out the pipe, refilled it, sucked noisily on the mouthpiece and applied a match to the bowl. "Well, I daresay you know the R.A.E. at Bedford—the Royal Aircraft Establishment, you know—began experimenting with automatic landings soon after the war," he continued. "In 'fifty-five, the Blind Landing Unit had worked out a system for the V-bombers of the R.A.F...that's —"

"Okay, okay, the Royal Air Force," Solo interrupted with a smile. "We do know that one."

"Roger and out!...Sorry, chaps. As I say, they worked out a system for the V-bombers, which of course had to be able to fly in any weather. And the bombers duly used it. But unfortunately it wasn't good enough for the civil airlines."

"Good grief, why not?"

"Margins of error, old boy. The R.A.F.'s prepared to accept a very small calculated risk—any operational war force must be, obviously. The particular figure determining things in this case was one fatality in one hundred thousand landings where the system was in full use."

"And this small percentage of calculated error was not good enough for civil planes?" Illya asked.

"Not by a long chalk. The Air Registration Board wouldn't certify full use of any equipment until it had proved a safety standard of one fatality per ten million landings...Nevertheless B.E.A. started using Smith's equipment on their Tridents in 1964. This controlled the aircraft's height until the moment of touchdown. Then B.O.A.C. equipped V.C. 10's with similar gear developed by Elliott-Bendix."

"Was this used on all landings?"

"No. Mainly for fog. A limited use in fact. They were waiting for the International Civil Aviation Organization to give the final go ahead on world-wide adoption of the system in principle."

"And the principle is?"

"Plances carry the equipment in a square box housed in the cockpit. As they approach the airport, the box fixes them on a localizer beam which brings them in line with the runway to be used for the landing. Then another ground transmitter broadcasts an electronic beam down which the plane rides, as it were, to establish the correct glide path."

"And the gear in the box causes the plane's controls to adjust themselves so as to maintain the correct altitude and inclination for touchdown?"

"Dead on target, old chap. Hole in one. The pilot still has to control the sideways aspect, the roll of his wings, himself—but the height's always the most difficult part of it, after all. And even in good weather this limited use of the stuff increases the safety factor no end."

"Aren't they developing an—er—extension to the system so that the roll factor will be taken care of too?"

"They are. Have, in fact. Supposed to be installed later this year. In the meantime, our own gear—the Murchison-Spears, you know—already takes care of this."

"Is it based on the same principles?" Illya asked.

The Technical Director struck a match and sucked the flame noisily into the sodden bowl of his pipe. "Partly," he replied. "Fact is, the gear that fixes the plane on the localizer beam is a dead crib—so far as that's possible within the copyright infringement laws. But the part that adjusts the height and inclination is quite different. Instead of relying on a ground-to-air electronic beam and riding down it, the Murchison-Spears equipment works on a system more like ordinary radar."

"You mean it emits a signal and deduces information from the way that signal is echoed back—then causes the aircraft to act upon this?"

"Broadly speaking, yes. Murchison designed the altitude-and-aspect end of it—that's simple in theory but extremely sophisticated in design. And Spears—he's the hydraulics wizard—handled the part that deals with the roll factor. Basically, this is just a sensitizer at each wing-tip and something very like the old-fashioned balance-pipe between them. But again—the means he used to achieve this are electronically most advanced. The sensitizers—which both transmit and receive pulses, after all—are extraordinarily compact and ingenious."

"How do you yourself account for the three T.C.A. crashes here?"

The man with the pipe lit another match. For some moments he puffed away behind his private smokescreenm, then he rose to his feet and crossed the room to the window. "Very difficult question to answer," he said at last, with his back to them. "Mind, I haven't had time to go over the bits—the actual pieces of wreckage of the latest one. They're being assembled on the floor in a hangar nearby, as nearly as possible in their original relationship to one another. And that's a hell of a job when you've got perhaps several tens of thousands of segments—buckled, torn, melted, twisted, distorted and what-not."

"I can imagine."

"Nevertheless, my chaps and I have formed certain opinions—and they are only opinions, based on interpretation of the information supplied by other bods, and not deductions from data observed by ourselves. That'll come later."

"Any opinion, any suggestion, any hint will be valuable, sir."

"Yes. Well—for what it's worth, all my chaps underwrite what the accident investigation johnnies said: that there was no human error in any of the three prangs. And that there was nothing wrong with any of the planes. Or with their normal controls, for that matter."

"You're saying, in effect, that there was something wrong with the Murchison-Spears equipment?"

"No, old boy. That's exactly what I'm not saying. I'm saying there was nothing wrong with anything else. You can draw what deductions you want to from that. In view of the fact that the M-S gear was proved to be in perfect condition after each crash, I simply cannot say that, ergo, it must have been the gear that was at fault. Until our own investigations have been completed, I must say nothing: my mind must remain open..."

"If the gear had been at fault, what would you say—unofficially, of course—would have been the—er—likeliest thing to have happened to it? That could have left it in perfect condition afterwards, that is."

"Seems obvious to me, old chap. In such a case—if one existed!—one would have to look for a set of conditions causing false readings on the equipment. Something that caused the box to direct the aircraft as though the ground wasn't where it really was...if you get my meaning!"

"You mean the box could have acted as though the runway was higher or lower than it really is, for example?"

"I mean," the Director said carefully, "I'd be inclined to look for a situation in which such a thing could happen."

"And if such a set of conditions existed—which part of the gear would you be inclined to suspect of being affected?"

"Look—the box divides itself pretty definitely into three separate complexes, doesn't it? The bit getting it in line with the runway to start with...and after that the altitude-and-aspect gear, and finally the wing-tip equipment that controls the roll. Right?"

"We're with you."

"Right. Now it would seem unlikely that the first is in any way affected: all three crashes actually occurred on the runway, so the planes must have been accurately lined up, eh?...And again, no eyewitnesses have mentioned anything like a sideslip or a wingtip digging in or anything of that sort. Admittedly the last one did cartwheel—but that was apparently only after the under-carriage had been wrecked on the first impact. So it seems—shall we say?—unlikely that the wingtip gubbins caused the crashes."

"Which leaves the altitude and glide-angle equipment?"

"Exactly. You examine all the witnesses' statements. Seventy per cent of 'em say something like 'the plane seemed to fly straight into the ground'. And the survivor of the last one was trying to say something to the nurse in the ambulance. Unfortunately, she didn't speak English—but we gather he was spouting something about height, or too high, or something. All of which seems to me to suggest either wrong altimeter readings or wrong glide angles."

"Or wrong interpretation by the gear to give the effect of this?"

The dark man with the moustache shrugged. For the first time, he removed the pipe from his mouth. "You must appreciate my position," he said, jetting a small cloud of smoke into the air. "We make the gear, after all. As there's no evidence of faultiness after the crash, we feel it's not up to us to ferret out reasons why it might have been at fault—though of course we should accept any conclusive evidence found by someone else."

"I understand," Solo said. "And you can't think of any device—or set of conditions, to use your phrase—under which the part of the gear affecting height readings or glide angle could be momentarily distorted, and yet return to normal afterwards?"

The Technical Director jammed the pipe back into his mouth. "Oh, have a heart, old chap," he said. "Have a heart."

Later, Solo and Illya spent some time studying the technical drawings of the Murchison-Spears equipment—with particular emphasis on those parts of it affecting the height of the aircraft and the automatic control of this.

"I can see the principle," Solo said. "But I'm afraid the detail is a bit too..."

"No, no, Napoleon," Illya said. "It is relatively simple. Look...after the scanner tube has...Look!...Here...This is where, if it was just giving a reading, the electronic pulse would be turned into a visual indication, on a dial. See?"

"Ye-e-es. I'm with you so far. Just."

"Well, since it's not just giving a reading—but causing the plane to react as a pilot would after digesting that reading—the electronic information feeds in...here. In this small memory storage unit."

"Something like a computer?"

"On a far less complicated scale, yes...And then these selectors...here...and here...and here...See, the contact is made by this core of toridium. As you know, it's a metal whose coefficient of expansion is —"