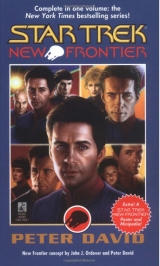

Текст книги "New Frontier Omnibus (Books 1-4: "House of Cards", "Into the Void", "The Two Front War", "End Game")"

Автор книги: Peter David

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

"Seed unfertile ground," Calhoun mused. "The parent race was all heart."

"Yeah, but apparently they weren't all-knowing." McHenry picked up the story. "The exiles were sent to a planet that had been described to them as inhospitable. But that's not what they discovered when they arrived there. The climate was fairly temperate, the world almost paradisiacal."

"Could they have arrived at the wrong planet?" asked Shelby.

"A logical conclusion," Soleta replied. "However, the coordinates for the intended homeworld of the criminals had been preset and locked into the ark's guidance systems. After all, the race didn't want to have their exiles taking control of the ship and heading off to whatever destination they chose. There do remain several possibilities. One is that the planet underwent some sort of atmospheric change. A shift in its axis, for example, causing alterations in the climate."

"Wouldn't that have changed the orbit and made the locating coordinates incorrect, though?" Shelby said.

"Yes," admitted Soleta. "Another possibility is that the present coordinates were simply wrong and they did not arrive at the intended world. Or perhaps someone within their race simply took pity on them and secretly made the change. It is frustrating to admit, but we simply do not know to a scientific certainty."

"What we do know," McHenry stepped in, "is that Thallon itself was an almost limitless supply of pure energy."

"Pure energy? I don't follow," Kebron said.

"Think of it as an entire world made of dilithium crystals," explained Soleta. "Not that it was dilithium per se, but that's the closest comparison. The ground is an energy-rich mineral unique to the world, all-purpose and versatile beyond anything that has ever been discovered elsewhere. The nutrients in it are such that anything planted in it grows. Anything.Pieces of the planet, when refined, were used to harness great tools of peace and growth . . ."

"And then, eventually, great tools of war," Mc-Henry said.

The tenor of the meeting seemed to change slightly, and when the mention of war came up, eyes seemed to shift to Si Cwan. He shrugged, almost as if indifferent. "It was before my time," he reminded them.

"With Thallon as their power base, they were able to launch conquest of neighboring worlds," McHenry said. "And then, once they had those worlds consolidated under their rule, they spread their influence and power to other nearby systems. In essence, they imitated the race which had deposited them there in the first place."

"What about this race you mentioned," asked Calhoun. "Was there a conflict with them? Did they ever return to Thallon and discover what they had wrought? Or did the Thallonians ever go looking for them?"

"No to the first, yes to the second," McHenry replied. "But they never found them. It's one of the great mysteries of Thallonian history."

"And great frustrations," Si Cwan put in.

"Understandable," Kebron rumbled. "Your ancestors wished to pay them back for the initial indignity of being dumped like refuse on another world."

"You see, Lieutenant Kebron," Si Cwan said with mild amusement, "you understand the Thallonians all too well. Perhaps we shall be fast friends, you and I.

" Kebron simply stared at him from the depths of his dark, hardened skin.

"The Thallonian homeworld has always been the source of the Thallonian strength, both physical and spiritual," said Soleta. "The events of the last weeks, including the collapse of their empire, may have been presaged by the change in the planet's own makeup. In recent decades, the planet seemed to lose much of its energy richness."

"Why?" asked Calhoun.

"Since the Thallonians were never able to fully explain how their world acquired its properties in the first place, there's understandably confusion as to why it would be deserting them now," said Soleta. "Still, the Thallonians might have been able to withstand those difficulties, if there had not been problems with various worlds within the Thallonian Empire."

"It was the Danteri," Si Cwan said darkly.

Calhoun seemed to stiffen upon the mention of the name. "You claimed that at the Enterprisemeeting, I understand. Do you have any basis for that?"

"The Danteri have always hungered to make inroads into our empire. They've made no secret of that, nor of their boastfulness. I believe that they instigated rebellion through carefully selected agents. If not for them, we could have—"

"Could have retained your power?"

"Perhaps, Captain. Perhaps."

"By the same token, isn't it possible," Calhoun said, leaning forward, fingers interlaced, "that the Danteri simply serve as a convenient excuse for the deficiencies in your own rule. That it was as a result of ineptitude among the rulers of the Thallonian Empire that the entire thing fell apart. That, in short . . . it was your own damned fault?"

There was dead silence in the room for a moment, and then, imperturbably, Si Cwan said once again, "Perhaps, Captain. Perhaps. We all have our limitations . . . and we all have beliefs which get us through the day. In that, I assume we are no different."

"Perhaps, Si Cwan. Perhaps," said Calhoun with a small smile.

Then Calhoun's comm unit beeped at him. He tapped it. "Calhoun here."

"Captain, this is Lefler. We're picking up a distress signal from a transport called the Cambon."

"Pipe it down here, Lieutenant."

There was a momentary pause, and then it came through the speaker. "This is the Cambon,"came a rough, hard-edged and angry voice, "Hufmin, Captain. We've sustained major damage in passing through the Lemax system. Engines out, life-support damaged. We have nearly four dozen passengers aboard—civilians, women and children—we need help." His voice seemed to choke on the word, as if it were an obscenity to them. "Repeating, to anyone who can hear . . . this is . . ." And then the signal ceased.

"Lefler, can we get them back?"

"We never had them, sir. We picked it up on an all-band frequency. He threw a note in a bottle and hoped someone would pick it up."

"Have we got a fix on their location?"

"I can track it back and get an approximate. If their engines are out, I can't pinpoint it precisely. On the other hand, they wouldn't have gone too far with no engine power."

"Our orders are to head straight for Thallon," Shelby pointed out.

Calhoun glanced at her. "Are you going to suggest that we ignore a ship in distress, Commander?"

There was only the briefest of pauses, and then Shelby replied, "Not for an instant, Captain. We're here for humanitarian efforts. It would be nothing short of barbaric to then ignore the first opportunity to deploy those efforts."

"Well said. McHenry, get up to the bridge and work with Lefler to find that ship. Get us there at fastest possible speed. Shelby—"

But she was already nodding, one step ahead of him as she tapped her comm unit. "Shelby to engine room."

"Engine room. Burgoyne here."

"Burgy, we're going to be firing up to maximum warp. You have everything ready to go?"

"For you, Commander? Anything. We're fully up to spec. Even I'm satisfied with it."

"If it meets your standards, Burgy, then it must measure up. Shelby out."

McHenry was already on his way, and Calhoun was half-standing. "If there's nothing else . . ."

But Si Cwan was shaking his head, as if discouraged about something. The gesture caught Calhoun's attention, and he said, "Si Cwan?"

"The Lemax system. I know the area. He must have tried to run the Gauntlet. It shouldn't have been a problem." He sighed.

"The Gauntlet?"

"It's a shooting gallery. Two planets that used to be at war, until we imposed peace upon them. The Gauntlet was a hazard of the past, except apparently the danger has been renewed. Just another example of the breakdown occurring all around us." He shook his head again, and then looked around at the silent faces watching him. And then, without another word, he rose and walked out of the room.

Si Cwan stared at the wall of his quarters. Then he heard the sound of the chime. He ignored it, but it sounded again. "Come," he said with a sigh.

Calhoun entered and just stood there, arms folded. "You left rather abruptly,"

"I felt the meeting was over."

"Generally it's good form for the captain to make that judgment."

"I am somewhat out of practice in terms of having others make judgments on my behalf."

Calhoun walked across the room, pacing out the interior much as Si Cwan had earlier. "How do you wish to be viewed aboard this ship, Cwan? As an object of pity?"

"Of course not," Si Cwan said sharply.

"Contempt, then? Confusion, perhaps?" He stopped and turned to face him. "Your title, accorded out of courtesy more than anything else, is 'Ambassador.' Not prince. Not lord. 'Ambassador.' I will hope you find that satisfactory. And by the same token, I hope you understand and acknowledge my authority on this ship. I do not want my decision to allow you to remain with us to be viewed by you as lack of strength on my part."

"No. I don't view it that way at all."

"I'm pleased to hear that."

Si Cwan regarded him thoughtfully for a moment. "May I ask how you got that scar?"

Calhoun touched it reflexively. "This one?"

"It is the most prominent, yes."

"To be blunt . . . I got it while killing someone like you."

"I see. And should I consider that a warning?"

"I don't have to kill anymore . . . I hope," he added as an afterthought.

They sat in silence for a moment, and then Si Cwan said, "It is important to me that you understand my situation, Captain. We oversaw an empire, yes. In many ways, in your terms, we might have been considered tyrannical. But it was my life, Captain. It was my life, and the life of those around me who worked to maintain it and help it prosper. Whether you agree with our methods or not, there was peace. There was peace,"and he slapped his legs and rose. He turned his back to Calhoun and leaned against the wall, palms spread wide. "Peace built by my ancestors, maintained by my generation. We had a birthright given to us, an obligation . . . and we failed. And now I'm seeing the work of my ancestors, and of my family, dismantled. In a hundred years . . . in ten years, for all I know . . . it will be as if everything we accomplished, for good or ill, will be washed away. Gone. As traceable as a tower of sand on the edge of a beach, consumed by the rising tide. What we did will have made no difference. It was all for nothing. Every difficult decision, every hard choice, ultimately amounted to nothing whatsoever. We have no legacy for our future generations. Indeed, we'll probably have no future generations. I have no royal consort with whom I can perpetuate our line. No royal lineage to pass on."

"And you're hoping to use this vessel to rebuild your power base. Aren't you."

Si Cwan turned and stared at him. "Is that what you think?"

"It's crossed my mind."

"I admit it crossed mine as well. But I give you my word, Captain, that I will do nothing to endanger this ship's mission, nor any of its personnel. My ultimate goal is the same as yours: to serve as needed."

Slowly Calhoun nodded, apparently satisfied. "All right. I can accept that . . . for now."

"Captain . . . ?"

"Yes."

Si Cwan smiled thinly. "You were aware the entire time, weren't you. Aware that I had stowed away on your vessel."

For a moment Calhoun considered lying, a course that he would not hesitate to indulge in if he felt that it would serve his purposes. But his instinct told him that candor was the way to go in this matter. "Yes."

"Good."

"Good?"

"Yes. It is something of a relief, really. The notion that I was aboard a ship where the commanding officer had so little awareness of what was happening around him . . . it was unsettling to me."

"I'm relieved that I was able to put your mind at ease. And Si Cwan . . ."

"Yes?"

"Believe it or not . . . I can sympathize. I've had my own moments where I felt that my life had been wasted."

"And may I ask how you dealt with such times of despair?"

And Mackenzie Calhoun laughed softly and said, "I took command of a starship." But then he held up a warning finger. "Don't get any ideas from that."

"I shall try not to, Captain. I shall try very hard."

X.

HUFMIN STARED OUTat the stars and, focusing on one at a time, uttered a profanity for every one he picked out.

Cramped in the helm pit of the Cambon,he still couldn't believe that he had gotten himself into this fix. He scratched at his grizzled chin and dwelt for the umpteenth time on the old Earth saying that no good deed goes unpunished.

He glanced at his instrumentation once more, his lungs feeling heavier and heavier. He knew that the last thing you were supposed to do upon receiving a head injury was let yourself fall asleep. And so he had kept himself awake through walking around in the cramped quarters, through stimulants, recitation, biting himself—anything and everything he could think of. None of which was going to do him a damned bit of good because, just to make things absolutely perfect, he wasn't going to be able to breathe for all that much longer. The life-support systems were tied into his engines. When they went down, the support systems switched to backup power supply, but that was in the process of running out. Hufmin was positive it was getting tougher to breathe, although he wasn't altogether certain how much of that was genuine and how much was just his imagination running away with him. But if it wasn't happening now, it was going to be happening soon enough as the systems became incapable of cleansing the atmosphere within the craft and everybody within suffocated.

Everybody . . .

Every . . . body . . .

. . . lots of bodies.

Not for the first time, he dwelt on the fact that this was a case where the more was most definitely not the merrier. Every single body on the ship was another person who was taking up space, another person breathing oxygen and taking up air that would be better served to keep him, Hufmin, alive.

What had possessed him? What in God's name had possessed him to take on this useless, unprofitable detail? If he'd been a Ferengi he would have been drummed out of . . . well, whatever it was that Ferengi were drummed out of when they made unbelievably bad business decisions. The problem was that this was no longer simply a case of costing him money. Now it was going to cost him his life.

. . . lots of bodies . . .

"Dump 'em," he said, giving voice finally to the thought that had bounced around in his head for the last several hours. It was a perfectly reasonable idea. All he had to do was get rid of the passengers and he could probably survive days, maybe even weeks, instead of the mere hours that his instruments seemed to indicate remained to him.

It wouldn't be easy. There were, after all, fortyseven of them and only one of him. It wasn't likely that they would simply and cheerfully hurl themselves into the void so that he, Hufmin, had a better chance at survival. No, the only way to get rid of them would be by force. Again, though, he was slightly outnumbered . . . by about forty-seven to one.

He had a couple of disruptors in a hidden compartment under his feet. He could remove those, go into the aft section where all the passengers were situated, and just start firing away. Blow them all to hell and gone and then eject the bodies. But then he pictured himself standing there, shooting, body after body going down, seeing the fear of death in their eyes, hearing the death rattles not once, not twice, but forty-seven times. Because it was going to have to be all of them. All or nothing, he knew that with absolute certainty. He couldn't pick and choose. All or nothing. But he was no murderer. He'd never killed anyone in his life; the disrupters were just for protection, a last resort, and he'd never fired them. Never had to. Kill them and then blast them into space . . . how could he . . . ?

Then he realized. He didn't have to kill them. Just blast them into space, into the void. Sure, they'd die agonizingly, suffering in space, but it wasn't as if death by disrupter was all that much better.

The Cambonwas divided into three sections: The helm pit, which was where he was. The midsection, used for equipment storage mostly, and his private quarters as well. And the aft section . . . the largest section, used for cargo . . .

. . . which was where all his passengers were. They were cramped, they were uncomfortable, but they were alive.

Hufmin's eyes scanned his equipment board. And there, just as he knew it would be, was the control for the aft loading doors. There were controls in back as well, but they were redundant and—if necessary—could be overridden from the helm pit. The helm pit, which was, for that matter, selfcontained and secured, a heavy door sealing it off from the rest of the vessel.

All he had to do was blow the loading-bay doors. The passengers back there probably wouldn't even have time to realize that their lives were ended before they were sucked out into the vacuum of space. Granted he'd lose some air as well. With power so low, the onboard systems would never be able to replenish what he lost to the vacuum. On the other hand, he'd have the remaining air in the helm pit and in the midsection. Not a lot, but at least it would be all his. All his.

. . . lots of bodies . . .

The bay-door switch beckoned to him and he reached over and tapped it, determined to do what had to be done for survival before he thought better of it. Immediately a yellow caution light came on, and the operations computer came on in its flat, monotone masculine voice. "Warning. This vessel is not within a planetary atmosphere. Opening of loading-bay doors will cause loss of air in aft section and loss of any objects not properly secured. Do you wish to continue with procedure? Signify by saying, 'Continue with procedure.'"

"Con—" The words caught in his throat.

. . . lots of bodies . . .

"Con . . . contin—"

There was a rapping at the door behind him. It reverberated through the helm pit, like a summons from hell. "What is it?!"he shouted at the unseen intruder.

"Mr. Hufmin?" came a thin, reedy voice. A child's voice, a small girl. One of the soon-to-be corpses.

"Yeah? What?"

"I was . . . I was wondering if anyone heard our call for help."

"I don't know. I wish I did, but I don't. Go back and sit with your parents now, okay?"

"They're dead."

That caught him off-guard for a moment, but then he remembered; one of the kids had lost her parents to some rather aggressive scavengers. She was traveling with an uncle who looked to be around ninetysomething. "Oh, right, well . . . go back with your uncle, then."

There was a pause and he thought for a moment that she'd done as he asked. He started to address the computer again when he heard, "Mr. Hufmin?"

"What is it, damn you!"

"I just . . . I wanted to say thank you." When he said nothing in response, she continued, "I know you tried your best, and that I know you'll keep trying, and I . . . I believe in you. Thank you for everything."

He stared at the blinking yellow light. "Why are you saying this? Who told you to say this?" he asked tonelessly.

'The gods. I prayed to them for help, and I was starting to fall asleep while I was praying . . . and I heard them in my head telling me to say thank you. So I . . . I did."

Hufmin's mouth moved, but nothing came out. "That's . . . that's fine. You're, uh . . . you're welcome. Okay? You're welcome."

He listened closely and heard the sound of her feet pattering away. He was all alone once more. Alone to do what had to be done.

"Computer."

"Waiting for instructions," the computer told him. The computer wouldn't care, of course. It simply waited to be told. It was a machine, incapable of making value judgments. Nor was it capable of taking any actions that would insure its own survival. Hufmin, on the other hand, most definitely was.

"Computer . . ."

He thought of the child. He thought of the bodies floating in space. So many bodies. And he would survive, or at least have a better chance, and that was the important thing. "Computer, continue with . . ."

What was one child, more or less? One life, or forty-seven lives? What did any of it matter? The only important thing was that he lived. Wasn't that true? Wasn't it?

He envisioned them floating past his viewer, their bodies destroyed by the vacuum, their faces etched in the horror of final realization. And he would still be alive . . .

. . . and he might as well be dead.

With the trembling sigh of one who knows he has just completely screwed himself, Hufmin said, "Computer, cancel program."

"Canceling," replied the computer. Naturally, whether he continued the program or not was of no consequence to the computer. As noted, it was just a machine. But Hufmin liked to think he was something more, and reluctantly had to admit that—if that was the case—it bore with it certain responsibilities.

He leaned back in his pilot's seat, looked out at the stars, and said, "Okay, gods. Whisper something to menow. Tell me what an idiot I am. Tell me I'm a jerk. Go ahead. Let me have it, square between the eyes."

And the gods answered.

At least, that's what it appeared they were doing, because the darkness of space was shimmering dead ahead, fluctuating ribbons of color undulating in circular formation.

Slowly he sat forward, his mind not entirely taking in what he was witnessing, and then the gods exploded from the shadows.

These gods, however, had chosen a very distinctive and blessed conveyance. They were in a vessel that Hufmin instantly recognized as a Federation starship. It had dropped out of warp space, still moving so quickly that it had been a hundred thousand kilometers away and then, an eyeblink later, it was virtually right on top of him. He'd never seen such a vessel in person before, and he couldn't believe the size of the thing. The ship had coursecorrected on a dime, angling upward and slowing so that it passed slowly over him rather than smashing him to pieces. He saw the name of the ship painted on the underside: U.S.S. Excalibur.The ship was so vast that it blotted out the light provided by a nearby sun, casting the Camboninto shadow, but Hufmin could not have cared less.

Hufmin had never been a religious man. The concept of unseen, unknowable deities had been of no interest to him at all in his rather pragmatic life. And as he began to deliriously cheer, and wave his hands as if they could see him, he decided that he did indeed believe in gods after all. Not the unknowable ones, though. His gods were whoever those wonderful individuals were who loomed above him. They had come from wherever it was gods came from, and had arrived in this desperate environment currently inhabited by one Captain Hufmin and his cargo of forty-seven frightened souls.

Thereby answering, finally, a very old question, namely:

What does God need with a starship?

And the answer, of course, was one of the oldest answers in the known universe:

To get to the other side.

XI.

ROBIN LEFLER LOOKED UPfrom Ops and said, " Captain, everyone from the vessel has been beamed aboard: the ship's commander and forty-seven passengers."

Shelby whistled in amazement as Calhoun said, clearly surprised, "Forty-seven? His ship's not tiny, but it's not thatbig. He must have had people plastered to the ceiling. Shelby, arrange to have the passengers brought, in shifts, to sickbay, so Dr. Selar can check them over. Make sure they're not suffering from exposure, dehydration, et cetera."

"Shall we take his ship in tow, sir?" asked Kebron.

"And to where do you suggest we tow it, Mr. Kebron?" asked Calhoun reasonably. "It's not as if we've got a convenient starbase nearby. Bridge to Engineering."

"Engineering, Burgoyne here," came the quick response over the intercom.

"Chief, we have a transport ship to port with an engine that needs your magic touch."

"My wand is at the ready, sir."

"How many times have I heard thatline," murmured Robin Lefler . . . just a bit louder than she had intended. The comment drew a quick chuckle from McHenry, and a disapproving glance from Shelby . . . who, in point of fact, thought it was funny but felt that it behooved her to keep a straight face.

"Get a team together, beam over, and give me an estimate on repair time."

"Aye, sir."

He turned to Shelby and said briskly, " Commander, talk to the pilot. Find out precisely what happened, what he saw. I want to know what we're dealing with. Also, see if you can find Si Cwan. He's supposed to be our ambassador. Let's see how his people react to him. If they throw things at him or run screaming, that will be a tip off that he might not be as useful as we'd hoped. Damn, we should have given him a comm badge to facilitate—"

"Bridge to Si Cwan," Shelby said promptly.

"Yes," came Si Cwan's voice.

"Meet me in sickbay, please. We have some refugees there whom we'd like you to speak with."

"On my way."

Shelby turned to Calhoun. "I took the liberty of issuing him a comm badge. He's not Starfleet, of course, but it seemed the simplest way to reach him."

"Good thinking, Commander."

She smiled. "I have my moments," and headed to the turbolift.

The moment she was gone, though, Kebron stepped over to Calhoun and said, "Captain, shall I go as well?"

"You, Kebron? Why?"

"To keep an eye on Cwan."

"What do you think he's going to do?"

"I don't know," Kebron said darkly. He seemed to want to say something more, but he kept his mouth tightly closed.

"Lieutenant, if you've got something on your mind, out with it."

"Very well. I feel that you have made a vast mistake allowing Si Cwan aboard this vessel. He could jeopardize our mission."

"If I believed he could, I would never have allowed him to remain."

"I'm aware of that, sir. Nevertheless, I feel it was an error."

"I generally have a good instinct about people Lieutenant. I've learned to trust it; it's saved my life any number of times. If you wish to disagree with me, that is your prerogative."

"Then I'm afraid that's how it's going to remain, Captain, until such time as I'm convinced otherwise."

"And when do you think that will be?"

Zak Kebron considered the question. "In Earth years, or in Brikar years?"

"Earth years."

"In Earth years?" He paused only a moment, and then responded, "Never."

Shelby entered sickbay and looked around at the haggard faces of the patients in the medlab. Immediately her heart went out to them. They were a mixture of races, with such variations of skin colors between them that they looked like a rainbow. But there was unity in the fact that they were clearly frightened, dispossessed, with no clear idea of what lay ahead for them. Dr. Selar was going about her duties with efficiency and speed. Shelby noticed that Selar and her people already seemed to be working smoothly and in unison. She felt some relief at that; Calhoun had mentioned that there'd been some difficulty between Selar and one of her doctors, but Shelby wouldn't have known from watching them in action.

"I'm looking for the commander of the vessel," she said to the room at large.

One of the scruffier individuals stepped forward. "That would be me." He stuck out a hand. "Name's Hufmin."

"Commander Shelby, second-in-command."

"You people saved our butts."

"That's what we're here for," she told him, even as she thought, Did I justsay that? I sound like something out of the Star fleet Cliché Handbook.

And then Shelby saw the attitude of the people in sickbay change instantly, as if electrified. A number who were on diagnostic tables immediately jumped off. One even pushed Dr. Selar aside so he could scramble to his feet. They were all looking past Shelby's shoulder. She turned to see that, standing behind her, was Si Cwan.

There was dead silence for what seemed an infinity-to her, and then a young woman, who appeared to be in her early twenties by Earth standards, seemed to fly across the room. She threw her arms around Si Cwan so tightly that it looked as if she'd snap him like a twig, even though she came up barely to his chest.

"You're alive, thank the gods, you're alive," she whispered.

And now the others followed suit. Most of them did not possess the total lack of inhibition of the first woman. They approached him tentatively, reverently, with varying forms of intimidation or respect. Si Cwan, for his part, stroked the young woman's thick blue hair as gently as a father cradling his newborn child. He looked to the others, stretching out his free hand as if summoning them. They seemed to draw strength from his mere presence, many of them genuflecting, a few had their heads bowed.

"Please. Please, that's not necessary," said Si Cwan. "Please . . . get up. Don't bow. Don't . . . please don't," and he gestured for them to rise. "Sometimes I feel that such ceremonies helped create the divide between us that led to . . . to our present state. Up . . . yes, you in the back, up."

They followed his instructions out of long habit. "This ship is bringing you back to power, Lord Cwan?" asked one of the men. "They'll use their weapons on your behalf?"

Shelby began to state that that was uncategorically not the case, but with a voice filled with surprising gentleness, Si Cwan said, "This is a mission of peace, my friends. I am merely here to lend help wherever I can." And then he glanced briefly at Shelby as if to say, A satisfactory answer?She nodded in silent affirmation.

Then Shelby turned back to the refugees and said, "What were you all fleeing from?"

A dozen different answers poured out, all at the same time. The specifics varied from one individual or one group to the next, but there were common themes to all. Governments in disarray, marauders from an assortment of races, wars breaking out all over for reasons ranging from newly disputed boundaries to attempted genocide. A world of order sliding into a world of chaos.

"We just want to be safe," said the young woman who had so precipitously hugged Si Cwan. "Is that too much to ask?"

"Unfortunately," sighed Si Cwan, "sometimes the answer to that is yes."