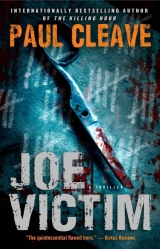

Текст книги "Joe Victim"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Praise for Paul Cleave’s

previous international bestsellers

The Laughterhouse

“An intense adrenaline rush from start to finish, I read The Laughterhouse in one sitting. It’ll have you up all night. Fantastic!”

–S. J. Watson, New York Times bestselling author of Before I Go to Sleep

“Cleave is a master of evoking the view askew; delving into the troubled psyches of conflicted characters. Former cop and convict Theo Tate, stumbling forward in search of some sort of redemption, returns to the scene of his first crime scene, hunting a killer and kidnapper set on revenge. Ferocious storytelling that makes you think and feel. A bloodstained high point in Cleave’s already impressive oeuvre.”

–New Zealand Listener, A Best Book of 2012

“This dark, gripping thriller, the latest in the Tate saga, is as hard-boiled as it gets. The surprise ending suspends all disbelief. Like a TV series that ends its season on a cliff-hanger, you won’t want to wait until next year. This will leave the reader clamoring for the next book in the series.”

–Suspense Magazine

“Piano wire–taut plotting, Tate’s heart-wrenching losses and forlorn hopes, and Cleave’s unusually perceptive gaze into the maw of a killer’s madness make this a standout chapter in his detective’s rocky road to redemption.”

–Publishers Weekly (starred)

“Theodore Tate is the quintessential flawed hero, a damaged soul hunting deviants in a forest of moral quandaries. . . . The novel is less a character study than a dissection of the need for, and cost of, revenge. . . . Cleave’s horrific narrative takes no prisoners, with the bloody action relentlessly ricocheting around Christchurch at a pace that leaves the detectives near collapse. . . . An intense and bloody noir thriller, one often descending into a violent abyss reminiscent of Thomas Harris, creator of Hannibal Lecter.”

–Kirkus Reviews

“A wonderful book . . . The final effect is that tingling in the neck hairs that tells us an artist is at work.”

–Booklist (starred)

cemetery lake

“Cleave is a powerful writer, conjuring a malevolent atmosphere, creating a relentless momentum propelling Tate deeper into a moral swamp. . . . Contemporary crime noir at its best, mined from the dark pit of the human psyche.”

–Kirkus Reviews

“Tate is hardly the first dark, brooding detective with a tragic past in crime fiction, but he brings a fresh twist to the familiar type, as does the setting of Christchurch, New Zealand, which Cleave evokes with masterful precision.”

–Booklist

“Reminiscent of James Ellroy . . . [an] uncompromising portrayal of a man in torment . . . fully absorbing.”

–Publishers Weekly (starred review)

To Stephanie (BB) Glencross and Leo (BBB) Glencross.

We’ll always have Turkey . . .

Prologue

SUNDAY MORNING

Well, live and learn.

I suck in a deep breath, close my eyes, and squeeze all the way on the trigger.

The world explodes.

It explodes with light and sound and pain, and it’s not right, because it should be exploding with darkness. There should be a shroud of black enveloping me, taking me away from all of this. I’m in control—Slow Joe is a winner—and proof of this comes when my life starts flashing in front of me. The darkness is mere moments away, but first I must go through images of my mother, my father, my childhood, time spent with my auntie. Hours and hours of footage from my life is broken up into snapshots then condensed into a two-second movie, one scene flicking into the next like watching an old film projector. The images speed up. They flash through my mind.

But that is not all.

Sally is flashing across my mind. No, not my mind, but my field of vision. She is right in front of me, against me, her clumpy body pressing me all over in the way she has always wanted to. There are a dozen voices.

I hit the pavement and my arm flies out to the side. Sally’s flesh is pushed aside by my body. It rolls over my limbs, trying to swallow me like a soft couch. I’m not dying yet, but I’m already in Hell. I pull the trigger without any target, and it turns out without any success because the gun is no longer in my hand. Sally is crushing the air out of me and I’m still not real sure what’s going on. The world is topsy-turvy and there is a packet of cat food pressed up against my shoulder. My face is burning and is wet with blood. There is high-pitched screaming in my ear, a monotonous tone that won’t end. Sally is pulled off me, she disappears only to be replaced by Detective Schroder, and I have never been so relieved in my life. Schroder will save me, Schroder will take Sally and hopefully lock her away in the kind of place fat girls like Sally ought to be locked away.

“I’m . . .” I say, but I can’t even hear my voice over my ringing ears. I can’t figure out what’s going on. I’m so confused. The world is shifting off its axis.

“Shut up,” Schroder yells, but I can hardly hear him. “You hear me? Shut up before I put a Goddamn bullet in your head!”

I have never heard Schroder talk that way, and I guess for him to talk that way to Sally means he’s really, really pissed off at her for jumping on me. I suddenly feel closer to him than I ever have. But the pain I’m in, the fact that Fat Sally just folded her flesh around me, now I’m thinking I want the bullet he’s offering her. I want that sweet, sweet darkness and the silence that will come along with it. But I stay quiet. Mostly.

“I’m Joe,” I shout, in case they can all hear the ringing tone too. “Slow Joe.”

Somebody hits me. I don’t know who, and I don’t know if it’s a punch or a kick, but it comes out of nowhere and my head snaps to the side and Schroder disappears for a moment and the side of my apartment building appears. I can see the top floor and the guttering, I can see dirty windows and cracked windows and somewhere up there is my apartment, and all I want to do is make my way inside and lie down and try to figure out what’s going on. It all goes blurry and seems to run into the ground, like the colors of a watercolor painting all leaking away, leaving only reds, and it stays that way as I’m dragged up onto my feet. My clothes are wet because the sidewalk is wet because it rained all night.

“I forgot my briefcase,” I say, and it’s true. In fact I have no idea where it is.

“Shut. The fuck. Up, Joe,” somebody says.

Joe? I don’t understand—is it me these people are being mean to, and not Sally?

I can’t feel my hands. My arms are behind me and they’re locked so tight they won’t move. My wrists hurt. I’m pulled along, my feet stumbling, and I try to focus on the ground and I try to focus on what is happening and can do neither, not until I look over at Sally and the men restraining her, Sally with tears on her face and suddenly the last sixty seconds all come flooding back to me. I was walking home. I was happy. I had spent the weekend with Melissa. Then Sally had pulled onto my street and accused me of lying to her, accused me of being the Christchurch Carver, then the police had shown up, then I’d . . . I’d tried to shoot myself.

And failed, because Sally had jumped on me.

The ringing in my ears fades a little, but everything stays red. There’s a police car ahead of me that wasn’t there a few minutes ago when Sally pulled onto the street. One of the men dressed in black opens the rear door. There are lots of men in black, all of them with guns. Somebody mentions an ambulance and somebody says “No way” and somebody else says “Just bloody shoot him.”

“Jesus, he’s getting blood all over the seat,” somebody says.

I look down, and sure enough, there’s enough of my blood all over the seat and floor to keep some cleaner just like me disgruntled for a few hours. There’s a trail of it leading back to my gun. Sally is standing over there no longer being restrained. Her face and clothes splattered with blood. My blood. She has this wet look on her face that makes me feel sick in ways I can’t identify. She’s staring at me, probably trying to figure a way to climb into the backseat of the car and crush herself all over me again. Her blond hair that was in a ponytail a few minutes ago is now hanging loosely, and she takes a few strands of it and starts chewing on the ends—a nervous tic, I guess, or a seductive gesture for the two police officers standing next to her who, if they see her doing it, might just try to blow their own brains out like I did.

I blink the redness away and a few seconds later it starts flowing back into my field of vision.

Two guys enter the car up front. One of them is Schroder. He gets behind the wheel. He doesn’t even look around at me. The second guy is dressed in black. Like Death. Like the rest of them. He’s carrying a gun that looks like it could do a lot of damage, and the guy gives me the kind of look that suggests he wants to see just how much damage it can do. Schroder starts the car and turns the siren on. It seems louder than any other siren I’ve heard before, as if it has more of a point to make. I don’t get to put on a seat belt. Schroder pulls away from the side of the road, jumping forward so fast I nearly fly out of the seat. I twist around to see another car pulling in behind us, and behind that is a dark van. I watch my apartment building get smaller and I wonder what kind of mess it’s going to be in when I get home tonight.

“I’m innocent,” I say, but it’s like I’m talking to myself. Blood enters my mouth when I speak and I like the taste of it, and I know that if we were to drive back home we’d see Sally licking her fingers, liking the taste of it too. Poor Sally. She has brought these men to me in a storm of confusion, and what was becoming the best weekend of my life seems to be heading down a path of the worst. How long will it take me to explain my actions, to convince them of my innocence? How long until I can get back to Melissa?

I spit the blood out.

“Jesus, don’t fucking do that,” the man in the front seat says.

I close my eyes, but my left one doesn’t close properly. It’s hot, but not painful. Not yet anyway. I straighten up and get a look at myself in the rearview mirror. My face and neck are covered in blood. My eyelid is flopping about. I shake my head and it slips over my eye like a leaf. It’s not hanging on by much. I try to blink the eyelid back into place, but it doesn’t work. Hell, I’ve had worse. A lot worse. And again I think of Melissa.

“What the hell you smiling at?” Man in Black asks.

“What?”

“I said what the hell—”

“Shut up, Jack,” Schroder says. “Don’t talk to him.”

“The son of a bitch is—”

“Is a lot of things,” Schroder says. “Just don’t talk to him.”

“I still think we should pull over and make it look like he tried to escape. Come on, Carl, nobody would care.”

“My name is Joe,” I say. “Joe is a good person.”

“Cut the bullshit,” Schroder says. “Both of you. Just shut up.”

My neighborhood races by. The sirens on the police cars are flashing and I guess they’re in a hurry to let me prove what they already know about me—that I’m their Slow Joe, I’m their buddy, I’m their friendly, warm-feeling retard, a trolley-pusher of the world who only ever tries to please. People in other cars are pulling over for the traffic train, and people on the street are turning to look. I’m in a parade. I feel like waving. The Christchurch Carver is in handcuffs, but nobody knows it’s really him. They can’t do. How can they?

We hit town. We drive past the police station with no slowing down. Ten stories of boredom that show no signs of getting less boring anytime soon. I will be out tomorrow to begin my new life with Melissa. We keep driving. Nobody talks. Nobody hums anything. I start to get the feeling that Schroder has changed his mind, and they are going to make it look like I escaped, only it’ll be me escaping from somewhere outside of the city limits where nobody can watch me gunned down. My clothes are soaked in blood and nobody seems to care. I’m not so sure they can be cleaned up. We stop at a set of red lights. Jack is staring in the rearview mirror as though trying to unlock a puzzle. I stare back at him for a few moments before looking down. My legs are covered in red drops and smears. My eyelid is hurting now. It feels like it’s been rubbed in stinging nettle.

We come to a stop at the hospital. A bunch of patrol cars form a semicircle around us. It’s starting to rain. We’re a month away from winter and I’m getting a bad feeling I’m not going to get to see it. Jack does the gentlemanly thing and opens the door for me. The other men in black do the less gentlemanly thing and point their guns at me. Doctors and patients and visitors are staring at us from the main doors. They’re all motionless. I figure we’re putting on quite the show. I’m helped out of the car. Things are fine, I think, except they’re not. Sitting down they were fine, but not standing up. Standing up the world is full of handcuffs and guns and blood loss. I start swaying. I drop to my knees. Blood flicks off my face onto the pavement. At first Jack seems about to try and stop me from falling any further, but then he thinks better of it. I topple forward. I can’t bring my hands around to break my fall, and the best I can do is turn my head away from the ground so the damaged eyelid points to the sky, but for some reason I get confused—probably because I’d been staring at it in the rearview mirror for the last few minutes—so I end up turning that part of my face toward the ground. I can see lots of boots and the bottom half of a car. I can see two hungry-looking police dogs being restrained on leashes. Somebody puts a hand on me and rolls me. My eyelid is left behind on the wet parking lot pavement, surrounded by blood. It looks like a slug has been murdered down there, an invertebrate crime scene, where soon other slimy little fuckers will try and figure out what happened.

Only that slimy wad of flesh belongs to me. “That’s mine,” I say, feeling the heat from the wound worm its way through the rest of my body. My eye is watering and blinking doesn’t work. I do what I can, a ragged line of skin hangs like a way-too-short curtain over my eye.

“This?” Jack says, and he steps on it distastefully as if grinding a cigarette butt into the ground. “This was yours?”

Before I can complain they pick me up and I’m moving again. Even though it’s an overcast day, the world is bright and I can’t blink any darkness into it, not on my left side anyway. I can’t blink the sweat or the blood or the pain away either. A team of men surround me and I can hear them talking among themselves. I can hear them hating the laws that require them to bring me here when their ethics suggest otherwise. They think I’m a bad person, but they have it all wrong.

A doctor approaches. He looks scared. I’d look scared too if I saw a dozen armed men coming toward me. Which I saw for the first time about ten minutes ago. Everybody else near the main doors are either standing with hands over their mouths, or standing with cell phones in their hands and filming the action. News networks all over the country will be showing some of this footage today. I try to imagine what effect that will have on Mom, but my imagination doesn’t stretch that far because I become distracted by the doctor.

“What’s going on here?” the doctor asks, and it’s a good question, except it’s coming from a guy who’s in his fifties wearing a bow tie, and that makes him somebody worth staying away from.

“This . . .” Schroder starts, and he seems to struggle for the next word. “Man,” he spits out, “needs medical treatment. He needs it now.”

“What happened?”

“He walked into a door,” somebody says, and a group of men start to laugh.

“Yeah, he was clumsy,” another man says, and more men laugh. They’re bonding. They’re using humor to start coming down from whatever high they’re on. A high I gave them. Except for Schroder and Jack and the doctor. They look deadly serious.

“What happened?” the doctor asks again.

“Self-inflicted gunshot,” Schroder says. “Grazed him deep.”

“Looks worse than a graze,” the doctor says. “You really need this many men around?”

Schroder turns back and seems to do a mental count. He looks like he’s about to nod and say they could do with a few more, but instead he signals to about half the team and tells them to stay put. I’m pushed in a wheelchair and my hands are uncuffed only to be recuffed to the arms of it. They wheel me down a corridor and lots of people keep looking at me as if I’ve just won a Mr. Popularity contest, but the truth is nobody knows who I am. They never have. We pass some pretty nurses that on any other day I’d try to follow home. I’m put on a bed and cuffed to the railing. They strap my legs down and I can’t move. They strap and cuff everything so tight it feels like I’m encased in concrete. They must think I have the strength of a werewolf.

“Detective Schroder,” I say, “I don’t understand what’s going on.”

Schroder doesn’t answer. The doctor comes back over. “This is going to be a little painful,” he says, and he’s half right, getting the little wrong, but nailing the painful. He prods the wound and examines it and shines a torch into it, and without the ability to blink it’s like staring at the sun.

“This is going to be more than a few hours’ work,” he says, almost talking to himself, but loud enough for the others to hear. “Going to need some real detailing here to give him any kind of functionality, and also to minimize scarring,” he says, and it sounds like he’s about to give an estimate then tell us how much it’s going to be for the parts. I just hope he has them in stock since mine is still out in the parking lot.

“We don’t care about scarring,” Schroder says.

“I care,” I say.

“And I care too,” the doctor says. “Damn it, the eyelid is completely gone.”

“Not completely,” I say.

“What do you mean?”

“It’s back at the car. On the ground.”

The doctor turns to Schroder. “His eyelid is out there?”

“What’s left of it,” I say, answering for Schroder, who then answers for himself by shrugging.

“You want this guy out of here quicker, we’re going to need that eyelid,” the doctor says.

“We’ll get it,” Schroder says.

“Then get it,” the doctor says. “Otherwise we have to graft something else that will work. And that’ll take longer. Can’t have him not blinking.”

“I don’t care if he can’t blink,” Schroder says. “Just cauterize the damn thing and glue a patch on his face.”

Instead of arguing or telling Schroder he’s out of line, the doctor finally seems to realize that all these cops, all the tension, all the anger, that must mean something special. I can see it occurring to him, I watch through one good eye and one bloody eye and he starts to frown, then slowly shake his head, a curious look on his face. I know the question is coming.

“Just who is this man?”

“This is the Christchurch Carver,” Schroder answers.

“No way,” the doctor says. “This guy?”

I’m not sure what that’s supposed to mean. “I’m innocent,” I say. “I’m Joe,” I say, and the doctor jams a needle into the side of my face, the world shifts further off its axis, and things go numb.

TWELVE MONTHS LATER

Chapter One

Melissa pulls into the driveway. Sits back. Tries to relax.

The day is fifty degrees maximum. Christchurch rain. Christchurch cold. Yesterday was warm. Now it’s raining. Schizophrenic weather. She’s shivering. She leans forward and twists the keys in the ignition, grabs her briefcase, and climbs from the car. The rain soaks her hair. She reaches the front door and fumbles with the lock.

She strolls through to the kitchen. Derek is upstairs. She can hear the shower going and she can hear him singing. She’ll disturb him later. For now she needs a drink. The fridge is covered in magnets from bullshit places around the country, places with high pregnancy rates, high drinking rates, high suicide rates. Places like Christchurch. She opens the door and there are half a dozen bottles of beer and she puts her hand on one, pauses, then goes for the orange juice instead. She breaks the seal and drinks straight from the container. Derek won’t mind. Her feet are sore and her back is sore so she sits at the table for a minute listening to the shower as she sips at the juice as her muscles slowly relax. It’s been a long day in what is becoming a very long week. She’s not a big fan of orange juice—she prefers tropical juices, but orange was her only option. For some reason drink makers think people want their juices full of pulp that sticks in your teeth and feels like an oyster pissing on your tongue, and for some reason that’s what Derek wants too.

She puts the lid back on the juice and puts it into the fridge and looks at the slices of pizza in there and decides against them. There are some chocolate bars in a side compartment. She peels one open and takes a bite, and stuffs the remaining bars—four of them—into her pocket. Thanks, Derek. She finishes off the open one while carrying the briefcase upstairs. The stereo in the bedroom is pumping out a song she recognizes. She used to have the album back when she was a different person, more of a carefree, CD-listening kind of person. It’s The Rolling Stones. A greatest-hits package, she can tell by the way one song follows another. Right now Mick is screaming out about blotting out the sun. He wants the world to be black. She wants that too. He sounds like he’s singing about the middle of winter at five o’clock in New Zealand. She hums along with it. Derek is still singing, masking every sound she is making.

She sits down on the bed. There’s an oil heater running and the room is warm. The furniture is a good match for the house, and the house looks like somebody ought to take a match to it. The bed is soft and tempts her to put her feet up and prop a pillow behind her and take a nap, but that would also be tempting the bacteria in the pillowcase to make friends with her. She pops open the briefcase and takes out a newspaper and reads over the front page while she waits. It’s an article about some guy who’s been terrorizing the city. Killing women. Torture. Rape. Homicide. The Christchurch Carver. Joe Middleton. He was arrested twelve months ago. His trial begins on Monday. She is also mentioned in the article. Melissa X. Though the article also mentions her real name, Natalie Flowers, Melissa only thinks of herself as Melissa these days. Has done for the last couple of years.

A couple of minutes go by and she’s still sitting on the bed when Derek, wiping a towel at his hair, steps out of the bathroom surrounded by white steam and the smell of shaving balm. He has a towel wrapped around his waist. A tattoo of a snake winds its way from the towel up his side and over his shoulder, with its tongue forking across his neck. Some of the snake is finely detailed, parts of it really just sketched outlines with more to follow. There are various scars that go hand in hand with a guy like Derek, no doubt an even mixture of good times and bad times—good times for him and bad times for others.

She lowers the newspaper and smiles.

“What the hell are you doing here?” he asks.

Melissa turns the briefcase toward him and reaches out and presses pause on the stereo. The briefcase actually belongs to Joe Middleton. He left it with her the same day he never came back. “I’m here with the other half of your payment,” she says.

“You know where I live?”

It’s a stupid question. Melissa doesn’t point it out to him. “I like to know who I’m doing business with.”

He unwraps the towel from his waist, the entire time keeping his eyes on the cash in the briefcase. His dick sways left and right as he starts drying his hair.

“It’s all there?” he asks, still drying his hair, his face at the moment behind the towel and his voice muffled.

“Every dollar. Where’s the stuff?”

“It’s here,” he says.

She knows it’s here. She’s been following him ever since their initial meeting two days ago, where she gave him the first half of the payment. She knows he picked up the stuff only an hour ago. He went from there to here with no stops in between with a bag full of items his parole officer wouldn’t be too pleased about.

“Where?” she asks.

He wraps the towel back around his waist. She figures she could have just come in here and shot him and searched the house anyway, but she needs him. The stuff probably won’t be hard to find. She figures a guy who would ask You know where I live? to somebody standing in their bedroom is the kind of guy who hides things in the roof space or under the floor.

“Show me,” he says, nodding toward the money.

She slides the briefcase toward him on the bed. He steps forward. The twenty grand is made up in fifty– and twenty-dollar bills. They’re stacked neatly into piles with rubber bands around them. Over the last few years most of her income has been through blackmailing people or burglaries, some from the men she’s killed, but a few months ago she came into some pretty good money. Forty thousand dollars, to be precise. He thumbs through some of it and decides it must all be there.

He moves over to the wardrobe. He drags a box of clothes out then lifts the patch of carpet and digs a screwdriver into the edge of the floor and Melissa finds herself rolling her eyes, thinking how lucky guys like Derek are that they can’t be charged for stupidity along with other crimes. He pries up the boards. He pulls out an aluminum case the length of his arm. Melissa stands up so he can lay it on the bed. He pops the lid open. There is a rifle broken into separate pieces, all of it slotting into foam cutouts.

“AR-fifteen,” he says. “Lightweight, uses a high-velocity, small-caliber round, extremely accurate. Scope too, as requested.”

She nods. She’s impressed. Derek may be stupid, but being stupid doesn’t mean you can’t be useful. “That’s half of it,” she says.

He goes back to the manhole. Reaches in and pulls out a small rucksack. It’s mostly black with plenty of red trim. He sits it on the bed and opens it. “C-four,” he says. “Two blocks, two detonators, two triggers, two receivers. Enough to blow up a house. Not enough to do much more. You know how to use it?”

“Show me.”

He picks up one of the blocks. It’s the size of a bar of soap. “It’s safe,” he says. “You can shoot it. Drop it. Burn it. Hell, you can even microwave it. You can do this,” he says, and starts to squeeze it. “You can mold it into any shape. You take one of these,” he says, and picks up what looks like a metal pencil, only with wires coming from the end of it, “and stab it in. Attach the other end to these receivers,” he says, “then it’s just a matter of firing the trigger. You’ve got a range of a thousand feet, further if it’s line of sight.”

“How long does the battery in the receiver last?”

“A week. Tops.”

“Anything else I need to know?”

“Yeah. Don’t mix them up,” he says, and holds up one of the remotes. “See this piece of yellow tape I’ve put across it? It lines up with the piece of tape I’ve put on this detonator. So this,” he says, holding up the detonator with the tape, “goes with this,” he says, holding both the remote and detonator together.

“Okay.”

“That’s it,” he says, and starts packing them into the bag.

“I need your help doing something else,” she says.

He keeps putting things away. “What kind of something?”

“I want you to shoot somebody,” she says.

He looks up at her and shakes his head, but the question doesn’t faze him and doesn’t slow down his packing. “That’s not my thing.”

“You sure?” She holds up the newspaper and shows him a picture of Joe Middleton, the Christchurch Carver. “Him,” she says. “You shoot him, and I’ll pay you what you want.”

“Huh,” he says, then shakes his head again. “He’s in custody,” he says. “It’s impossible.”

“His trial starts next week. That means transport every day, twice a day, back and forth from jail to the courthouse. Five days a week. That’s five times a week he’s going to step out of a police car and make his way into the courts, and five times a week he’s going to step back out of the courts and into a police car. I already have a spot where he can be shot from, and an escape route.”

Derek shakes his head again. “Things like that aren’t always as they seem.”

“What do you mean?”

“You think they’re just going to drive him the same way every day, and just drop him off outside the front door? That’s where your spot looks over, right?”

She hadn’t thought of that. “Then what?”

“They’re going to mix up the route. They’re going to try and get him there in secret. They might put him in a normal car. Or a van.”

“You think so?”

“A trial this big? Yeah. I’d put money on it,” he says. “So whatever plan you think you might be hatching, it isn’t going to work. Too many variables. You think you can just hide in the building somewhere and take a shot? Which building? Which direction is he coming from?”

“The courthouse doesn’t move,” she says. “That’s not a variable.”

“Uh huh. And which entrance will he be using? They’re going to mix that up too. That’s why whatever spot you think you’re going to shoot him from is probably not going to work.”

“What if I can find out the route? And the way he’ll be going into the courthouse?”

“How you going to do that?”

“I have my ways.”

He shakes his head. She’s getting sick of all the negativity. “Doesn’t matter,” he says. “It’s just too hard a job. Shooting somebody like Joe, nobody’s going to get away.”

“Who can help me?”

He puts a hand to his face and strokes the bottom of his chin. He gives it some serious thought. Then comes up with an answer. “I don’t know anyone.”

“I’ll pay you a finder’s fee,” she says, trying not to sound desperate, but the fact is she is desperate. She’d already had a shooter lined up for this, but it fell through. Now she’s running out of time.

“There is nobody,” he says. “Sourcing weapons is one thing,” he says, “but it’s not like I have a Rolodex full of people we can call if we want somebody dead. It’s the sort of thing you have to do yourself.”