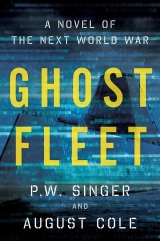

Текст книги "Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War"

Автор книги: P. Singer

Соавторы: August Cole

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Part 2

Attack your enemy where he is unprepared,

appear where you are not expected.

– Sun-Tzu, The Art of War

Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, Washington, DC

Armando Chavez exhaled when he made the initial slice. As his mentor Dr. Jimenez had explained so long ago, the key to precision was to move slow but steady, advancing the blade at a consistent pace. The cut complete, Chavez reached down, picked up the withered rose branch, and placed it into the faded canvas bag slung over his shoulder.

Landscaping was a step down for someone with an MD from Universidad Central de Venezuela. But it was the only kind of work Armando Chavez had been able to get since he’d arrived as a refugee from the chaos in his homeland seven years ago. He could get angry or he could focus on achieving the little perfections that made life satisfying.

As he trimmed the flowers at the base of the sign, he glanced at the etching in the black marble: Defense Intelligence Agency. He wasn’t sure what the DIA did. Hadid, his supervisor, said it was something like the CIA, but for the U.S. military. It didn’t matter. The landscaping crew was almost done here. After the break, Hadid said they would head over to trim the hedges behind the base’s elder-care center.

Because of security, the landscapers were not allowed inside the building. When break time came, the others gathered in the shade, but Chavez walked over to sit by the small decorative pond beside the entrance doors.

He flipped open the tablet he kept in his pocket to see if he had any messages. The screen projected a 3-D packet from his cousin back in Caracas. More pictures of his granddaughter. Such lovely eyes.

Armando’s smile went unnoticed by Allison Swigg as she cut across the grassy field by the pond in her rush from the parking lot. The imagery analyst had gotten stuck in the traffic on I-295 on her way back from a networking lunch out at Tysons Corner. And now she was late for the staff meeting.

Neither of them noticed the other, but as she passed the landscaper, his tablet recognized the RFID chips embedded in Swigg’s security badge. A localized wireless network formed for exactly 0.03 seconds. In that instant, the malware hidden in the video packet from Caracas made its jump.

As Chavez finished the iced tea his wife had made for him the previous night, Swigg approached the security desk manned by a guard in a black bullet-resistant nylon jumpsuit. A compact HK G48 assault rifle hung from the glossy gray ceramic vest that protected his chest. The only insignia on his uniform was the eagle-silhouette logo of the security company that guarded the DIA headquarters. No Personal Devices Allowed read the sign suspended above a row of silver turnstiles.

“Hey, Steve,” said Allison. “How’s the little one?”

“Pretty good,” the guard replied with a smile. “She slept through the night.”

She placed her iTab bracelet in a metallic lock box and pulled out the key. But Swigg’s badge stayed with her. As she walked toward the gate, the software in her badge automatically communicated her security clearance to the machine via a radio signal. And at the same moment of network linkage, the malware packet jumped again in less time than it would take to read the engraving on the entrance wall: Committed to excellence in defense of the nation.

The idea of using covert radio signals to ride malware into a network unconnected to the wider Internet had actually been pioneered by the NSA, one of the DIA’s sister agencies. But like all virtual weapons, once it was deployed in the open cyberworld, it offered inspiration for anyone, including one’s enemies.

The turnstile gate lifted. Swigg rushed down the hall, too far behind schedule to make her ritual stop at the Dunkin’ Donuts stand just inside the spy agency’s entrance. By the time she had passed the old Soviet SS-20 ballistic missile that stood mounted in the lobby like a Cold War totem pole, the malware packet had jumped from the gate onto another security guard’s viz glasses. When the guard walked his rounds, the packet jumped into the environmental controls that cooled a closet full of network servers supporting aerial surveillance operations over Pakistan. After that, it went to an unmanned-aircraft research and development team’s systems. And bit by bit, the malware worked its way into the various subnetworks that linked via the Defense Department’s SIPRNet classified network.

The initial penetrations didn’t raise any alarms among the automated computer network defenses, always on the lookout for anomalies. At each stop, all the packet did was link with what appeared to the defenses as nonexecutables, harmless inert files, which they were, until the malware rearranged them into something new. Each of the systems had been air-gapped, isolated from the Internet to prevent hackers from infiltrating them. The problem with high walls, though, was that someone could use an unsuspecting gardener to tunnel underneath them.

Shanghai Jiao Tong University

A thin teenage girl stood behind a workstation, faintly glowing metallic smart-rings on all her fingers, one worn above each joint. Her expression was blank, her eyes hidden behind a matte-black visor. Rows of similar workstations lined the converted lecture hall. Behind each stood a young engineering student, every one a member of the 234th Information Brigade – Jiao Tong, a subunit of the Third Army Cyber-Militia.

On the arena floor, two Directorate officers watched the workers. From their vantage point, the darkened arena seemed to be lit by hundreds of fireflies as the students’ hands wove faint neon-green tracks through the air.

Jiao Tong University had been formed in 1896 by Sheng Xuanhuai, an official working for the Guangxu emperor. The school was one of the original pillars of the Self-Strengthening Movement, which advocated using Western technology to save the country from destitution. Over the following decades, the school grew to become China’s most prestigious engineering university, nicknamed the Eastern MIT.

Hu Fang hated that moniker, which made it seem as if her school were only a weak copy of an American original. Today, her generation would show that times had changed.

The first university cyber-militias had been formed after the 2001 Hainan Island incident. A Chinese fighter pilot had veered too close to an American navy surveillance plane, and the two planes crashed in midair. The smaller Chinese plane spun to the earth and its hot-dogging pilot was killed, while the American plane had to make an emergency landing at a Chinese airfield on Hainan. As each side angrily accused the other of causing the collision, the Communist Party encouraged computer-savvy Chinese citizens to deface American websites to show their collective displeasure. Young Chinese teens were organized online by the thousands and gleefully joined in the cyber-vandalism campaign, targeting the homepage of everything from the White House to a public library in Minnesota. After the crisis, the hacker militias became crucial hubs of espionage, stealing online secrets that ranged from jet-fighter designs to soft-drink companies’ negotiating strategies.

That had all taken place before Hu Fang was born. She’d grown up sick from the smog; a hacking cough kept her from playing outside with the other kids. What Hu thought was a curse became a blessing: her father, a professor of computer science in Beijing, had started her out writing code at age three, mostly as a way to keep her busy inside their cramped apartment. Hu had been inducted into the 234th after she’d won a software-writing competition at the age of eleven.

Officially, militia service fulfilled the Directorate’s universal military service requirement, but Hu would have volunteered anyway. She got to play with the latest technology, and the missions the officers gave her were usually fun. One day it might be hacking into a dissident’s smartphone, and another day it might entail tangling with the IT security at a Korean car designer. The Americans, though, were the best to toy with – so confident of their defenses. If you pwned them – the word taken from the Americans’ own lingo for seizing digital control – the officers of the 234th noticed you. She’d done well enough that the apartment she and her father lived in now was much bigger than any of her father’s colleagues’.

But it was not the reward that mattered to Hu; rather, it was escaping the physical limitations that had once defined her life. When linked in, Hu felt like she was literally flying. Indeed, her gear worked on the same principles as the fly-by-wire controls on China’s J-20 fighter. The powerful computers she drew on created a three-dimensional world that represented the global communications networks that were her battlegrounds. She was among the few people who could boast that they had truly “seen” the Internet.

Hu had made her mark by hacking phones belonging to civilian employees in the Pentagon. Despite the restrictions on employees bringing devices into the building, a few did so every day. Her technique involved coopting a phone’s camera and other onboard sensors to remotely re-create the owner’s physical and electronic environment. This mosaic of pictures, sounds, and electromagnetic signals helped the Directorate produce an almost perfect 3-D virtual rendition of the Pentagon’s interior and its networks.

She noticed with pleasure her pump kicking in. Access to the latest in medical technologies was another perk of the unit. The tiny pump, implanted beneath the skin near her navel, dumped a cocktail of methylphenidate and other stimulants into her circulatory system.

Originally designed for children with attention deficit disorder, the mix produced a combination of focus and euphoria. For well over a decade, kids in America had popped “prep” pills to tackle tests and homework, which Hu thought was laughable. It was another sign of America’s weakness, kids using this kind of power just to make it through schoolwork. Hu’s pump enabled her to do something truly important.

When she’d been told a week ago to prepare for a larger operation than they’d ever tried, she hacked the pump’s operating system. It was a risk, but it paid off. She raised the dose level by 200 percent. No more steady-state awareness. Now it was like falling off a skyscraper and discovering you could fly right before you hit the ground.

Hu moved her hands like a conductor, gently arcing her arms in elliptical gestures, almost swanlike. The movement of each joint of every finger communicated a command via the gyroscopes inside the smart-ring; one typed out code on an invisible keyboard while another acted as a computer mouse, clicking open network connections. Multiple different points, clicks, and typing actions, all at once. To the officers watching below, it looked like an intricate ballet crossed with a tickling match.

The young hacker focused on her attack, navigating the malware packet through the DIA networks while fighting back the desire to brush a bead of sweat off her nose with her gloved hands. The Pentagon’s autonomous network defenses, sensing the slight anomalies of her network streams, tried to identify and contain her attack. But this was where the integration of woman and machine triumphed above mere “big data.” Hu was already two steps ahead, building system components and then tearing them down before the data could be integrated enough for the DIA computers to see them as threats. Her left arm coiled and sprung, her fingers outstretched. Then the right did the same, this time a misdirect, steering the defense code to shut down further external access, essentially tricking the programs into locking the doors of a burning house, but leaving a small ember on the outside for them to stamp on, so they’d think the fire was out.

Having gained access, she set about accomplishing the heart of her mission. Hu’s hands punched high, then her fingers flicked. She began inserting code that would randomize signals from the Americans’ Global Positioning System satellite constellation. Some GPS signals would be off by just two meters. Others would be off by two hundred kilometers.

Of course, shutting it all down would be easy. But she could swing that hammer later; today was all about sowing doubt and spreading confusion.

332 Kilometers Above the Earth’s Surface

If it weren’t so frustrating, it would be funny.

Less than a millimeter’s worth of extra metal on just one bolt was about to derail an operation that involved literally billions of moving pieces of software and hardware.

“Are you done yet?” asked Lieutenant Colonel Huan Zhou, an unmistakable edge in his voice.

The wrench that Major Chang Lu held in his gloved hand was a perfect copy of a HEXPANDO, just like the one that Colonel Farmer was banging at the ISS hatch with half an Earth orbit away. This wrench, though, had been produced from a design pirated by a patriotic hacker unit based in Shenzhen and manufactured at the Manned Space Engineering Office in Beijing. The problem was that, unlike the wrench, the bolt that Chang was trying to pry free was not a perfect copy and had become stuck. He pushed harder and harder, but it still wouldn’t budge.

“Nearly,” said Chang.

He saw the three other taikonauts reentering the Tiangong-3 space station. Lucky bastards.

The Tiangong (“Heavenly Palace”) space station program had been planned ever since China launched its first manned crew into space, in 2003. Western commentators had mocked those early Shenzhou vessels as poor copies of the United States’ 1960s-era Gemini spacecraft. But the program rapidly advanced, aided by a healthy amount of NASA computer design files that found their way into Chinese engineers’ hands. After the Shenzhous came the first Tiangong space station, a ten-meter-long, eight-thousand-kilogram single-module test bed that launched in 2011. It was the equivalent of NASA’s 1970s-era Skylab. That was followed in 2015 by the multimodule Tiangong-2, which was fifteen meters long and weighed twenty thousand kilograms, comparable to NASA’s 1990s design of the first ISS. Soon after, the program accelerated fast enough to finally match its competitors. Western commentators no longer mocked but instead marveled that in a decade and a half, China had achieved what it had taken NASA sixty years to accomplish.

The twenty-five-meter-long, sixty-thousand-kilogram Tiangong-3 space station was the pride of the nation, its launch celebrated with an official state holiday. It had seven modules laid out in a T, including a core crew module that could support six taikonauts; four solar panels that extended out a hundred and twenty feet; and a docking port that could accommodate four ships. At the two upper ends of the T were parallel laboratory modules designed to conduct various experiments in microgravity.

At least, that was what the rest of the world thought. The port-side module actually had a different purpose. And now, its cover just wouldn’t shake free, all because of a single faulty titanium bolt.

Chang realized that to get enough torque to pry the bolt loose, he’d have to untether, which was against protocol.

“Repositioning,” said Chang.

“Negative,” said Huan. “Return and I will send someone to finish your work.”

“There’s no time,” said Chang. “I’m now off tether.”

Chang heaved on the long wrench, and the bolt loosened. He easily removed the hatch cover and found himself staring into the mirrored surface of a laser’s lens. He studied the Earth’s reflection in it, and his own form superimposed above the peaceful blue beneath.

“Done,” said Chang.

“I didn’t think you had it in you, Chang. Good work,” said Huan, the edge in his voice gone.

Chang resecured himself to the space station and made his way to the main hatch while Huan brought Tiangong-3’s weapons online. The station crew had realized they were moving to war footing twelve hours ago when Huan switched off the live viz feed of their activities. But it still felt slightly unreal.

Once the taikonauts were all inside the station, Huan powered up the weapons module. The chemical oxygen iodine laser, or COIL, design had originally been developed by the U.S. Air Force in the late 1970s. It had even been flown on a converted 747 jumbo jet so the laser’s ability to shoot down missiles in midair could be tested. But the Americans had ultimately decided that using chemicals in enclosed spaces to power lasers was too dangerous. The Directorate saw it differently. Two modules away from the crew, a toxic mix of hydrogen peroxide and potassium hydroxide was being blended with gaseous chlorine and molecular iodine.

This was really it, thought Chang as he watched the power indicators turn red. There was no turning back once the chemicals had been mixed and the excited oxygen began to transfer its energy to the weapon. They would have forty-five minutes to act and then the power would be spent.

The firing protocol for mankind’s first wartime shots in space was well rehearsed. The targets marked in the firing solution had been identified, prioritized, and tracked for well over a year in increasingly rigorous drills the crew eventually realized were not just to support war games down on Earth. The long hours spent in the lab would finally pay off.

“Ready to commence firing sequence,” said Huan. “Confirm?”

One by one, the other taikonauts checked in from their weapons stations. Chang touched the photo taped to the wall in front of him. His fingers lingered on the image of his beaming wife and their grinning eight-year-old son. The smiling Ming, missing his two front teeth, wore his father’s blue air force officer’s hat.

What the photo did not show was how upset his wife had been when he’d given Ming that hat the night before. She thought it made her son look like a prop in a Directorate propaganda piece.

He moved his hand away from the photo and began his part of the operation, monitoring the targeting sequence. He startled even Huan when he cried out, “Ready!”

For years, military planners had fretted about antisatellite threats from ground-launched missiles, because that was how both the Americans and the Soviets had intended to take down each other’s satellite networks during the Cold War. More recently, the Directorate had fed this fear by developing its own antisatellite missiles and then alternating between missile tests and arms-control negotiations that went nowhere, keeping the focus on the weapons based below. The Americans should have looked up.

Chang snuck another look at the photo and caught Huan pausing, his trigger finger lingering above the red firing button. He appeared to be savoring the moment. Then Huan gently pressed the button.

A quiet hum pervaded the module. No crash of cannon or screams of death. Only the steady purr of a pump signified that the station was now at war.

The first target was WGS-4, a U.S. Air Force wideband gapfiller satellite. Shaped like a box with two solar wings, the 7,600-pound satellite had entered space in 2012 on top of a Delta 4 rocket launched from Cape Canaveral.

Costing over three hundred million dollars, the satellite offered the U.S. military and its allies 4.875 GHz of instantaneous switchable bandwidth, allowing it to move massive amounts of data. Through it ran the communications for everything from U.S. Air Force satellites to U.S. Navy submarines. It was also a primary node for the U.S. Space Command. The Pentagon had planned to put up a whole constellation of these satellites to make the network less vulnerable to attack, but contractor cost overruns had kept the number down to just six.

The space station’s chemical-powered laser fired a burst of energy that, if it were visible light instead of infrared, would have been a hundred thousand times brighter than the sun. Five hundred and twenty kilometers away, the first burst hit the satellite with a power roughly equivalent to a welding torch’s. It melted a hole in WGS-4’s external atmospheric shielding and then burned into its electronic guts.

Chang watched as Huan clicked open a red pen and made a line on the wall next to him, much like a World War I ace decorating his biplane to mark a kill. The scripted moment had been ordered from below, a key scene for the documentary that would be made of the operation, a triumph that would be watched by billions.

“And there’s the one,” said Huan. “Chang, it is good for us all that you did not miss,” he said as he clicked the pen shut with a flourish.

“Indeed,” Chang said, and then, smiling, he ad-libbed, “I would save you the trouble and walk myself out the airlock. Resetting for target number two.”

Originally known as the X-37, USA-226 was the U.S. military’s unmanned space plane. About an eighth the size of the old space shuttle, the tiny plane was used by the American government in much the same way the shuttle had been, to carry out various chores and repair jobs in space. It could rendezvous with satellites and refuel them, replace failed solar arrays using a robotic arm, and perform many other satellite-upkeep tasks.

But the Tiangong’s crew, and the rest of the world’s militaries, knew the U.S. military also used USA-226 as a space-going spy plane. It repeatedly flew over the same spots at the same altitude, notably the height typically used by military surveillance satellites: Pakistan for several weeks at a time, then Yemen and Kenya, and, more recently, the Siberian border.

With its primary control communications link via the WGS-4 satellite now lost, the tiny American space plane shifted into autonomous mode, its computers searching in vain for other guidance signals. In this interim period, USA-226’s protocol was to cease acceleration and execute a standard orbit to avoid collisions. In effect, the robotic space plane stopped for its own safety, making it an easy target.

The taikonauts moved on down the list: the U.S. Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness system was next. These were satellites that watched other satellites. The Americans’ communications were now down, but once these satellites were taken out, the United States would be blind in space even if it proved able to bring its networks back online. After that was the mere five satellites that made up the U.S. military’s Mobile User Objective System, akin to a global cellular phone provider for the military. Five pulses took out the narrowband communications network that linked all the American military’s aerial and maritime platforms, ground vehicles, and dismounted soldiers. Then came the U.S. Navy’s Ultra High Frequency Follow-On (UFO) system, which linked all of its ships. It was almost anticlimactic, the onboard targeting system moving the taikonauts through the attack’s algorithm step by step, slowing down only when a cluster of satellites sharing a common altitude needed to be dispatched one by one.

The last to be “serviced,” as Huan dryly put it, was a charged-particle detector satellite. The joint NASA and Energy Department system had been launched a few years after the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster as a way to detect radiation emissions. A volley of laser fire from Tiangong-3 exploded its fuel source.

When Huan finally put the pen back in his suit pocket, there were forty-seven marks on the wall.

They had been told that the ISS would be taken care of “by other means.” On the other side of the Earth, discarded booster rockets were coming to life after months of dormancy. The boosters-turned-kamikazes advanced on collision courses with nearby American government and commercial communications and imaging satellites. The American ground controllers helplessly watched the chaos overhead, unable to maneuver their precious assets out of the way.

“I will run diagnostics and flush the laser power systems,” said Chang. He kept moving in order to avoid thinking about what was happening on the Earth’s surface below.

“Good,” said Huan. “Then see if you can pull up the imagery from the attack; I want to watch it again later.” Of course you do, thought Chang.

![Книга [Magazine 1966-07] - The Ghost Riders Affair автора Harry Whittington](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-07-the-ghost-riders-affair-199012.jpg)