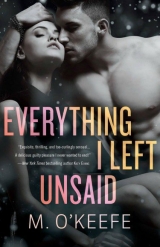

Текст книги "Everything I Left Unsaid"

Автор книги: Molly O'Keefe

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

ANNIE

In the dream, I was leading a crew of detasselers. Teenagers mostly, only a few years younger than me, but somehow they seemed so much younger. Childish with their summer jobs and packed lunches, the early hours making them grumble. One girl, despite being told to wear long-sleeved shirts and pants because corn rash was a bitch, stood there in cutoffs and a bikini top.

“You are going to get corn rash. And corn rash hurts,” I said, lifting my Del Monte cap and setting it back on my head over and over again. A nervous tic.

The girl glanced sideways at a boy who had his paper-bag lunch over the front of his jeans and was pretending so hard, so painfully hard, not to notice Bikini-girl’s attention that the corn could practically detassel itself, under the power of his discomfort and lust.

“I’ll be fine,” the girl said, flashing the boy the coyest of smiles.

“Stop saying that!” I yelled, startling everyone. I didn’t yell, as a rule. A rule I’d learned the hard way. I swore like a sailor, but I didn’t yell.

I took my clipboard with all the crew lists and the leaders and the fields they’d be going to and I started to smash the clipboard against the hood of my truck.

Stop. Smack. Fucking. Smack. Saying. Smack. That.

You will not be fine.

None of us will be fine!

I woke up, the tension reverberating up my arms, my hands clenched in painful fists. My heart pounded in my throat.

Did I yell? I waited, agonized, for the creak of the bed when Hoyt turned over. But he wasn’t there. His side of the bed was empty.

Where is he? Did I oversleep?

Quickly, I put it all together: the surprisingly great mattress, the sunlight through the beige curtains, the smell of Febreze.

The trailer.

Hoyt’s not here.

More importantly, I wasn’t there.

I could have wept.

There was a sudden pounding on the door and it felt like the top of my head might explode. That was the banging from the dream, someone at my door. Carefully, I pulled out the top drawer of the small bedside table between the bed and the wall of the trailer.

The black rubber grip of the .22 felt awful in my hand. Awkward. Cold, and both too big and too small.

“Annie McKay?” a voice asked, a Southern drawl coloring it.

It took me a second, freaking out as I was, but I finally recognized the voice. We don’t truck with no nonsense. That’s what that voice outside had said to me. It was Kevin, the guy in the office, knocking on the trailer door.

Adrenaline and relief made me dizzy.

And the fact that I hadn’t been sleeping or eating in days kept me dizzy.

The world was spinning.

“You don’t have a phone number for me to call,” he said, still talking through the weak metal door with the shitty lock. “And it’s half past nine. You said you were going to start work at eight.”

“Oh no,” I said, scrambling up. I’d slept in my clothes, despite the heat, ready to run if I had to. I wasn’t sure if that was still necessary, but I couldn’t quite convince myself not to do it. I put the gun back in the drawer and pushed my feet into my shoes. “Just a second!” I yelled.

I brushed my teeth too hard, too rushed, and I split my lip again.

“Shit,” I hissed, pressing cheap toilet paper to it.

“You coming, or what?”

“Sorry!” I yelled.

The toilet paper stuck to the cut and I left it there, looking like a guy who’d nicked his face shaving for church. In the mirror, my bruises seemed to be greener than they were yesterday. I put the scarf back on, despite how stupid it looked with my tee shirt and cutoffs, and then I put on my big movie-star sunglasses.

Could I be any more obvious? I wondered, carefully peeling the toilet paper from my lip.

But the thought of not wearing the scarf and the glasses made me feel naked.

So obvious won.

–

Kevin was a big man. Tall, wide, big stomach, big shoulders. His belly peeked out beneath his giant red tee shirt, already sweaty in the August North Carolina heat. He had big feet wedged into Adidas shower flip-flops that looked like they’d been welded on at some point. He wore his gray-black hair in a long ponytail down his back, with ponytail holders at regular intervals, keeping it all in line.

“Morning,” he said without much of a smile. He didn’t seem like a smiler.

Kevin was a still waters kind of guy. Or maybe he just didn’t give a shit.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, pushing up the edges of the scarf. “I overslept. I usually don’t sleep so late.”

Last night it had taken me hours to fall asleep. I’d jumped at every sound, and there were lots in the trailer park. People yelling, doors slamming. Wind and trees. A car alarm.

But finally I’d drifted off after two in the morning. Usually I’d be up at dawn, but sleep since I’d left Oklahoma had been in fits and starts.

And honest to God, who would have thought that mattress would be so comfortable?

“You’re the one who said you wanted to start today,” he said, his eyes wide under bushy eyebrows. “I thought you was nuts.”

“Nope, just broke.” When I’d asked about work in the area while doing the paperwork for the RV, he’d told me they were hiring at the park to do some groundskeeping, and I’d jumped at the opportunity.

Physical labor, right where I was living. I wouldn’t have to go into town. Meet other people.

My gut, which had been silent for my entire life—seriously, not a peep out of the thing for twenty-four years—had been yelling at me nonstop since I woke up on my kitchen floor two weeks ago. And my gut seemed to think this arrangement, this job, was not to be passed up.

“Did I tell you what you’ll be doing?” he asked, walking in front of me down the dirt track between my trailer and the next one.

“No. You just mentioned some lawn work.”

Kevin laughed, but I didn’t find any comfort in it. I had the distinct impression he was laughing at me. “Well, that was clever of me,” he said ominously.

The trailer next door was nearly identical to mine, though it seemed to be a newer model. White, where mine was totally ’70s beige, with a darker brown racing stripe down the side. American Dreamer written in sort of an old-timey Western print.

Yep, she was a beaut.

But the white RV next door had a wooden deck on the outside with a chair, a table, and an ashtray.

Deluxe.

I had trailer envy.

“Does anyone live there?” I jerked my thumb over my shoulder at the neighbor’s trailer.

“Joan,” Kevin said. “Keeps to herself. Not too friendly. If you’re smart you’ll stay away. She’s kind of a bitch.”

The skin on the back of my neck prickled as I walked by, as if someone was watching me from between two slats on the blinds. But when I glanced back there was nothing.

I’d been paranoid most of my life—it’s not like I could just make it stop.

“Ben, on the other hand,” he said, pointing past Joan’s trailer to the trailer the man…Dylan…had asked me to look in on.

Just the thought of his name electrified part of me, like a filament in a lightbulb starting to glow.

Don’t. Don’t think about him.

“Nice guy. Quiet, but not rude about it. Grows a hell of a garden.” He pointed over at the far end of the property, where I could see fencing and some plants.

Hardly sounds like a guy worth watching, I thought, wondering if Dylan wasn’t looking after the wrong person.

“Other side of the park,” Kevin said, jutting his chin out at the trailers just visible over a giant rhododendron bush, “that’s where the families are. Some are great. Some are screamers and drinkers and scene makers, so I try to keep the people without kids on this side.”

“Are you quarantining them? Or us?” I asked.

He gave me an arch look. “Hell if you won’t appreciate it by next Friday.”

Probably true.

We walked single file across a wooden bridge over a rain ditch that because of a recent storm was gurgling along happily under my feet.

Black-eyed Susans and forget-me-nots and tons and tons of Queen Anne’s lace covered the banks of the small stream. Crickets were loud and jumping into my legs. The highway was a bunch of miles in the distance, but I could feel the hum of trucks on asphalt rumbling in the boggy ground beneath my feet.

“It’s nice,” I said.

“What is?”

“This place.” I flung out a hand toward the flowers, the stream. A cricket smacked into the back of my leg and then buzzed away.

Kevin’s look made it clear he doubted my sanity. “You must see some real shit holes if this is nice.”

Oh Kevin, you don’t want to know.

Because the truth was, I hadn’t seen anywhere. Shit hole or otherwise.

Mom had been on a campaign practically since the moment of my birth to convince me that the world outside of the farm was a godless, terrible place. Full of selfish people doing selfish things. Men who’d want nothing but to hurt me, and women who’d look away while they did it.

When you are told that shit day in and day out, you start to believe it.

It’s probably why I stayed so long with Hoyt. Because the unknown was just so…unknown.

But here I was, in the thick of it, and so far, my new life was a million times better than my old life.

So, yes, it was nice.

“And here it is,” he said, coming to a stop in front of an overgrown field full of black garbage bags torn open by animals. Cans, dirty diapers, and newspapers spilled out in the weeds growing as tall as my head. He had to shout over the drone of black flies.

And the smell…

Oh dear God, I take back all that “nice” stuff.

Behind the wall of weeds was a giant oak with a ratty old rope hanging from one of the branches.

“What’s the rope for?” I asked, because surrounded by all this filth it looked like the scene of a terrible crime. The cover of a horror novel.

“Behind the weeds is a real nice watering hole.”

“That’s a watering hole?” I’d been joking about a weedy watering hole last night on the phone, but this was ridiculous.

“Kids play in it all summer, but it’s quiet now that they’re back in school.”

“So…what is this supposed to be?” I looked at the surrounding field. It was huge. An acre at least.

“The Flowered Manor Camp Ground,” he said.

“You’re joking.”

“Absolutely not.” Kevin looked only marginally affronted by my slack-jawed surprise.

“People actually camp here?”

“They will when you’re done.” He nudged my shoulder with his massive one and I was nearly knocked off my feet.

“You really can’t believe the things you read in a bathroom stall,” I muttered.

Dylan would laugh. The thought made me smile before I could stop myself and my lip split again. I licked away the warm copper tang of blood.

Dylan.

I remembered his laughing groan. Low and explict. Dirty, really. One of the dirtiest things I’ve ever heard. Last night, staring up at the plastic dimpled ceiling of the trailer, I’d convinced myself that the conversation had been a product of exhaustion. The fact was, stepping into the trailer for the first time, my fear slipping nervously into tentative relief, I’d been momentarily…not myself.

It would seem only logical that after the stress and focus of the last week, I’d go a little nuts.

And that’s what that conversation was. Nuts.

That’s why I’m not talking to him again.

Because in that wild nuts moment—that moment when I was just not myself—something had changed. Shifted.

And I wanted to talk to him.

I still did.

Which was weird, if not terrifying, because that bikini girl in my dream looking over at that boy, saying everything was fine, whose skin was about to be shredded—I’d already been her.

Only I had been wearing a wedding dress.

“Come on, now,” Kevin said. “I’ll show you our tools.”

Good. Right. Tools. Kevin led me over to a shed and opened the padlock on the door. “I’ll give you a key,” he said. “Once I’m sure you won’t steal nothing.”

“Steal?” I’d never been accused of stealing in my life.

“No offense,” he said. “But we’ve had some real unsavories looking in on this job.”

Inside the shed it looked like I’d have everything I needed for campground cleanup: a tractor mower, a weed whacker. Rakes, shovels. Granted, they were all older than I was, but I could work with it. There were even some gloves and boots by the door.

“You sure you want to do this?” Kevin looked sideways at me and I wondered what he saw. What story my scarf in August in North Carolina, my hair so black it swallowed the light, my increasingly alarming thinness, told him.

Probably nothing good. And frankly, probably a story far too close to the truth.

I am, after all, wearing the official costume of a woman on the run.

“I mean…you’re a kid, ain’t you?”

“No.” Childhood had blended right into adulthood for me, and there had been nothing in between. Like a rainbow that went from yellow right to indigo. “And I’m totally sure I want to do this.” I was used to physical labor at the farm. I liked it. And after a week on the road, I felt listless. Too in my head.

And my head was a shitty place to be.

“Suit yourself. Watch out for snakes.”

“What?” I squeaked.

“And bears.”

“You’re joking, right?”

He shrugged.

“That’s not funny, Kevin.”

“I don’t know, it kinda is.”

Kevin winked—which was weird in and of itself—before he lumbered off, leaving me unsure if he was joking or not.

For my own peace of mind I decided to go with joking. Physical labor—yes.

Snakes? No.

Bears? Hell no.

I traded my tennis shoes for the boots and slipped on the gloves. There was a box of black garbage bags and I tucked five of them in the back of my pants. I grabbed a shovel and rake and headed back over to the weed-and-garbage-filled field.

My feet slipped in the too big boots, but I was grateful for them when I stepped into the weeds and something squished underfoot and a wall of flies buzzed up and away.

The smell made me gag.

I pulled my scarf up over my nose. This is so gross.

But it was still better than what I’d left behind.

–

Back home, in the flatlands of Oklahoma, I’d been able to see for miles. And at the beginning of my marriage—not the very beginning, but when I realized that the chicken potpie incident wasn’t going to be a onetime thing—the openness seemed like protection.

Like a moat around me.

Hoyt couldn’t sneak up on me. I could be anywhere on the property, but I’d see the dust behind his truck rising up into the sky, long before I’d even see the truck. And in all that space, that open air, that blue sky with its towering clouds, my fear was like a radio signal that never bounced back. It just went and went and went—flying out over the prairie, fading away into silence.

And at some point during those days, at the beginning, anyway, I could empty myself of that fear. For just a few minutes. As if the dust and the work and the emptiness sucked it all from me.

It’s not like it was a huge transformative event. Like for a few minutes, I took off my clothes and sang Broadway tunes to the corn.

Hardly.

I just got to not be scared for a while.

And it was enough.

But here in Carolina, I was surrounded by a forest and insane amounts of kudzu vine. Which truthfully—as far as plants went—had to be the scariest plant. The way it climbed and grew over anything that stood still, preserving the shape of the thing underneath but killing it dead at the same time. Like a mummy plant.

So damn creepy.

There were strange animals in the forest. Strange bugs buzzing around my ears. Every noise made me jump and every shadow seemed to watch me.

Here, my fear bounced back at me tenfold.

Like I transmitted doubt and it came back as terror.

By the second hour of working, my entire body slick with sweat, I started to doubt if I’d gone far enough to get away from Hoyt. Because I was partially convinced he was watching me from the weeds around the watering hole.

“Hardly seems like a job for a girl,” a quiet voice said.

Wild, I turned, shovel over my head like a weapon.

“Whoa, there,” said an old man, lifting one arm up in the air. His other hand held a plate. “I take it back. It’s a perfect job for a girl.”

Heart thumping, I lowered the shovel. “Sorry,” I said, with the best smile I was capable of. “You startled me.”

“I can see that.” The man had a silver buzz cut and wore a pristine white tee shirt with a pair of jeans. On his forearm a tattoo snake twined its way around his elbow and an eagle was swooping down from his biceps, talons stretched to grab it.

“Here,” he said, holding out a plate toward me. “Watching you work made me hungry, so I figured you had to be starved.”

On the plate were two pieces of bread covered in mayonnaise and ragged slices of tomatoes, like they’d been cut with a spoon. The tomatoes were so red, so beautiful, they looked like gems. The juice like blood.

My stomach roared.

The old man’s lip twitched. “Go on,” he said pushing the plate toward me.

“I’m fine,” I said, squeezing my hand around the splintery wooden handle of the shovel. Hunger made me dizzy.

He shot me a puzzled look.

“Really,” I said. “Totally fine.”

“Well, I’ll leave it for you, then,” he said, setting down the old plastic plate on top of a boulder.

“You don’t need to—”

“I got about seven hundred pounds of tomatoes right now. I can’t eat them all myself.”

I had this half-clear, half-fuzzy memory of one of the last times Mom and I went to church, when it must have been getting obvious Mom was sick. The various circle groups and outreach ladies had unleashed an unprecedented wave of charity upon us. Tater-tot-covered casseroles, sheet cakes, a dozen kinds of chili, clothes, and blankets knit by hand—it all just rained down on us. So much that we couldn’t carry it all. There were hand squeezes and whispered, tearful promises to Mom that I would be looked after when she was gone.

I’d been relieved, delighted even. My fear of what would happen when Mom died was washed away in that flood of care. I had friends, I had community. I wasn’t totally alone. I didn’t need to lie awake at night scared, listening to Mom shuffle up and down the hallway, restless from the pain, and wonder what would happen to me.

Who would take care of me?

These people would!

Mom smiled at those friends, my potential new families, she nodded, made two trips to the car to get it all home, but once we were home and safe and alone, she went apeshit. Dumping all that free, delicious homemade food in the garbage.

We don’t need their pity, she’d said.

I do, I’d wanted to cry. I need their pity. And their chili!

We never went back to church after that and Mom died a few months later.

“Honestly, you’re doing me a favor,” the old man lied, but he did it without blinking, without smirking.

Oh, for God’s sake. Take the sandwich, I told myself, staring down at the juicy tomatoes resting on the bed of creamy mayonnaise. Wanting something doesn’t make it bad.

“Thank you,” I said. “I’ll eat it in a bit.”

I’d take the charity; I just wouldn’t eat it in front of him. Seemed reasonable.

He nodded as if accepting my terms. “How old are you, girl? If you don’t mind me asking.”

“Twenty-four.” Twenty-five in two months.

I waited for that “old soul” comment I used to get a lot. Old soul was code for a lot of things, and I figured most of them had nothing to do with my soul and more to do with growing up with my mother.

He nodded, saying nothing about my soul or age one way or another. “If I could offer a little advice, about the work?”

“Sure.”

“Start earlier. Out of the heat. Quit at noon. Ain’t nothing gonna come from working outside in August past noon except heatstroke. And drink more water.”

All of it I knew, but I’d been so flustered starting the day by sleeping in. Still, it would be rude to say “I know” when all he was doing was being polite. And frankly, he’d been kinder to me in two minutes than anyone had in a very long time.

So, I said, “Thank you for the advice. And the sandwiches.”

In reply, he ducked his head and walked away. Beneath the thin fabric of his white shirt I saw the shadow of a black tattoo in a strange shape, like a big square.

“I’m sorry,” I called out, though I was pretty sure I knew the answer to the question I was about to ask. “What’s your name?”

“Ben,” he said. “Yours?”

“Annie.”

“Pleasure to meet you, Annie.”

“Likewise, Ben.”

He walked back over to his trailer, the one two north from mine.

Ben was the man Dylan had watched.

Why?

Once he was out of sight I dropped the shovel and picked up the plate, nearly shoving one of the open-faced sandwiches in my mouth.

“Oh God,” I moaned around the mouthful of food. And then again because really…I’d had tomatoes before, and mayo and toasted cheap white bread. But somehow this combination, on this day—it was transcendent.

Flavors exploded in my mouth, sharp and sweet and tangy.

I scarfed both of them down, and used my finger to pick up the crumbs on the old plate.

If there were a dozen more on that plate, I’d eat them too.

The sun blazed overhead and my clothes were soaked and exhaustion made my feet weigh a hundred pounds.

My stomach was full, my hunger satiated.

Suddenly, I wished I could tell my mom that sympathy, pity, or concern—whatever it was that came with those tomatoes, much like the tater-tot casseroles—weren’t anything to be afraid of. Or angry over. They were no slight to pride or self-sufficiency.

All they were, really, was delicious.

And when you were hungry, they filled you up.