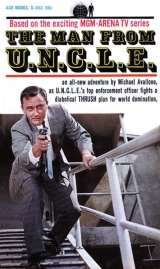

Текст книги "The Thousand Coffin Affair "

Автор книги: Michael Avallone

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

THE BADLY DRESSED CORPSE

“WHAT ARE YOU thinking about now, Solo?”

“The same thing you must be.”

“The corpse?”

“Yes. Any other time I would be thinking of you. But Stew’s corpse was enough to throw me into a tailspin. The fantastically quick decomposition…and the clothes. They were to mean something. He isn’t dressed that way because he was an eccentric.”

They were sitting quietly in the parlor of Herr Muller’s home, enjoying the solitude of each other’s company and a blissful cigarette. The smoke filled the air with lazy spirals of unbroken perfection until they collided with the beamed ceiling. Like most rural German homes, the Burgomeister’s house was mostly wooden.

Solo had had a frantic two hours upon their return from Stewart Fromes’ place. There had been the matter of the coffin. A cheap pine box, shaped nearly like a mummy case. With the mortician’s help and Jerry Terry’s aid, they had placed Steward Fromes in the coffin. Finally, they had secured enough ice to defer further decomposition for a few more hours. Solo had found some plastic bags in Fromes’ workshop which served. He had nothing more to do with the corpse other than to examine the reversed clothes. But there was nothing immediately apparent. No messages, no scraps of paper, no clues. Yet he knew for a fact that back in the U.N.C.L.E. laboratory something would be uncovered. Perhaps Stewart had treated his clothes with fluorescent materials or chemicals which would turn up under black light. It couldn’t end like this. Thrush hadn’t dressed him that way to be found by his friends. They weren’t in the business of leaving clues. No—the clothes had been Stew’s idea. Why?

Napoleon Solo didn’t know.

All he experienced now was a vast weariness of brain, limb and soul. He blinked across the room at Jerry Terry.

She was smiling at him. “If you want to talk, I’ll listen. We should both be tucked in our beds but you look like a man who can’t sleep—too much thinking to do.”

“Something like that,” he admitted.

“Any ideas?”

He puffed on the cigarette. “A few. The kind of things you have to drum up when you’re in the dark. I’m thinking about Stewart Fromes. What kind of a man he was—whatever I can remember about him. It’s screwy but I suddenly realize a lot of water has gone over the dam and we didn’t have much of a chance to get friendlier.”

“What was he like?” she asked softly.

“Brilliant. Won a medal in Korea. Majored in chemistry at Cornell, came out near the head of his class. He’d been with U.N.C.L.E. for nearly ten years. He was a bachelor, though he was almost hooked by a Hollywood actress once. That was his broken-heart period. He liked the Yankees, was a good golfer and—” Solo sat up, his eyes narrowing—“was an inveterate reader of mystery novels. Everything and anything. Fact is, we used to kid him about it.”

“You’ve thought of something?”

“Maybe.”

“Something constructive?”

It was odd, but the spurring softness of her voice filtering across the quiet room helped immensely. She was a sounding board for any and all ideas he might come up with—even crazy ones.

“I think so. But I’ll have to sleep on it.”

She, laughed lightly. “That’s a good one. Sleep where? The Burgomeister has no extra beds. I imagine these chairs are it for the rest of the night.”

He looked toward the windows. A dull glow of approaching dawn made the squared area ghostly

“German hospitality still has a Nazi flavor in some areas, I suppose. Just as well. You never know when you’re shaking hands with a man who stood by those ovens. It’s a creepy sensation. This chair will do me fine.”

“Napoleon—“

“I’m still here.”

She had left her chair to glide softly across the room. She was before him in an instant. A beautiful pixie with coppery hair and hauntingly lovely face. The crude lamps of the parlor made her face glow like some bronze goddess. She put her hands to his cheeks, bent and kissed him swiftly on the lips.

“We’re even now,” she whispered.

“New breed, huh?”

Her eyes narrowed. “Just what does that mean?”

“Well, you see what you want and you take it. I’m all for new breeds. Can’t tell. A little judicious mating and future generations may turn out not half bad—“

She was starting to get angry, color mounting in her cheeks. His bantering manner caused her to push away, averting her face. Solo laughed, reached out and pulled her back. He held her tightly so that her body was crushed against his own in the narrow confines of the chair. She squirmed, trying to get away from him, but he held her easily, almost as though she were a child.

He turned her around to face him, and said, “I really did mean that as a compliment, you know. If it didn’t sound completely serious, that’s only because of a peculiar quirk of mine—too many people I like have ended up dead, so I try not to take important things seriously anymore.”

“You’re a stinker,” she murmured, all the fight gone out of her.

“Takes one to know one, doesn’t it, Miss Terry?”

The chair was not the best place in the world to discover suddenly that they liked each other very much.

But they managed.

The utter stillness of the morning was staggering in its quietude. For a metropolitan man used to the throb and roar of big cities and thundering sidewalks, it proved a genuine soporific. Napoleon Solo had to be awakened.

He opened his eyes to see Jerry Terry’s lovely smile just inches from his eye.

“We have bacon and eggs,” she said happily. “Come on. Coffee’s on the boil and the good Mullers, both him and her, are off to City Hall to see about arrangements for getting us out of here.”

He sat up, rubbing his eyes and running fingers through his sleep-mussed hair.

Abruptly, the girl said, “Is Napoleon your real name?”

He pretended to be hurt. “Don’t you like it?”

“I love it. I simply noticed that you have the Bonaparte hairdo. That dark little forelock that dangles on your forehead.”

“I’ll cut it off,” he promised.

“You do and I’ll never talk to you again,” she vowed. “Come on. There’s a Civil War sink in the kitchen.”

The light, flippant talk was good. It helped drive away the worries, doubts and fears. The food was even better. Herr Burgomeister had a stocked larder that in another period of history would have made him suspected of black market affiliations.

Jerry Terry bustled around the kitchen, setting places and pouring coffee with all the animated enthusiasm of a new bride. Solo smiled in memory. The analogy would serve. The first time was always somehow, the best time. It had an aura of magic all its own.

“More coffee?”

“Please. Dare I hope there’s a wireless office in town? Strikes me I’d better get in touch with my people.”

“All you can do is ask Mr. Muller when he gets back.”

“Did you notice a railroad when we flew in last night?”

She shook her head. “It’s hard to tell from that altitude. Especially at night. But there has to be one around somewhere.”

He smiled grimly. “That ice won’t last forever. We have to do something, and quick. Unless our Mr. Waverly has a few rabbits up his sleeve.”

“Mr. Waverly?”

“My section chief. I’m sure he’s thought of something. What time do you have?” He checked his own wrist watch.

“Eleven fifteen.”

“Same here. Our watches are synchronized. Now, I’ll finish this coffee and we’ll shoot over to see about Fromes and that cablegram I have to send. Failing that, the phone is my next best bet.”

The coffin was secure on the wooden table where they had left it. Ignoring the cackling mortician who was asking in broken English what it was all about, Solo lifted the lid and re-examined Stewart Fromes.

The mixture was as before. The dead chemist looked as ghastly as before and his clothes still remained in their peculiar fixed reversal of the norm. It was uncanny. Fortunately, the ice seemed to have helped. The unpleasant odor of death was somewhat subdued.

“Jerry,” Solo said, without turning. “Would you ask the Herr Mortician to point out the direction of the cable office? Or someplace where we can use a phone?” She caught on quickly. Within seconds, she had charmed the old man from the room. Solo bent quickly over Stewart Fromes and made a closer survey than he had the night before.

The hands were hopelessly stiff. The decaying process was working fast. Fromes had worn no rings and his fingers were empty. His throat was free of pendants, lockets or identification disks of any kind. Solo worked quickly down the length of the body to the naked feet. It was there that he took his greatest effort. One by one, he pried the locked toes apart. It was gruesome work. Fromes’ flesh felt flaccid and loose, as if it would come apart at the touch of a finger.

Stewart Fromes had large feet but he had managed to keep them clean and fairly uncalloused. The toenails were in excellent condition. But between his fourth and little toe on the right foot, Napoleon Solo found the one item he was looking for. It was a repellant task but it had to be done.

A silver pellet, looking as innocuous as a B-B shot, fell into his palm. He held it up to the light, revolving it, his eyebrows knit in fierce concentration.

Here again was an intangible.

Had the pellet accidentally wedged itself between the corpse’s toes at some time prior to death? Had it been placed there to be found? By whom? Fromes…the enemy—or who?

There was no more time to guess. Jerry Terry was coming back, the mortician in tow, with Herr Muller bouncing excitedly behind them. The scrawny Burgomeister looked unhappy about something.

Napoleon Solo arched his eyebrows.

“Solo,” Jerry Terry said, there are merely three telephones in this thriving little town. Two are unavailable to us now because the people are away and Herr Burgomeister says his phone is on the blink. As for places where one can send telegrams—” She shook her head in sad negation.

That’s nice,” he said, pinning the Burgomeister with a look. “Where is the nearest place where we can contact civilization?”

Herr Muller forced an apologetic smile and held up his ten thin fingers.

“Ten kilometers. Bad Winzberg. I get car-truck. Drive you.”

“That’s good to know. Let me think a minute. There must be some better way—”

“The plane?” Jerry Terry asked.

He shook his head. “It wasn’t meant to ferry coffins. We can’t have Stew banging around like a load of apples. No, there has to be a better way. And I must contact my people—”

Herr Muller’s eyes took on a crafty gleam.

“You bury here. Why not? Fine cemetery. Later you dig up, re-bury in America, nicht yahr?”

Solo hesitated, visibly. “What cemetery?”

Herr Muller’s eyes widened in pride.

“You don’t know? Orangeberg. Biggest cemetery in all this part of country. Back in wartime was left by Allies. Three, maybe four hundred dead there. Not far. We reach there in half hour from here. Close to Black Forest.”

“You mean a cemetery for American soldiers. War memorial?” Solo had never heard of one in this part of the world, but then, he had not heard of everything.

“Nein, nein,” Herr Muller protested, with the mortician adding his gutturals to the chorus. “Our cemetery. For our people. Very nice there. You see. Like, like—” He searched for a proper word. “Like your Arlington in America!”

Jerry Terry looked at Napoleon Solo. Her face was faintly bemused but her eyes held refusal.

“Thanks for the offer, Herr Muller. But it’s no dice. I must take my friend back to the States. And right away. Now, if you’ll see about that truck, we’ll get him ready.”

Herr Muller was pained. “You will not reconsider—“

“Sorry. No.”

“But, but—”

The spluttering of Herr Muller was suddenly drowned out in the mammoth roar of a motor directly overhead—a thundering, blasting boom of sound which seemed to make the four walls of the mortuary rattle. A dish fell somewhere and a tin cup clattered. Jerry Terry shouted with pleasure as Solo raced to the doorway for a look.

High overhead, he could see the briskly clawing giant helicopter as it climbed quickly over the rooftops of the town. There was no mistaking the circling pattern of the flight. Solo stood and watched, smiling widely as he made out the American insignia and markings of the Air-Sea Rescue. By God, he would get Stewart Fromes home after all.

“Mr. Waverly,” he muttered feelingly, “thank you, very much.”

DEATH FOR THE DEBONAIR

STEWART FROMES’ corpse was on its way back to the States. It would be delivered to U.N.C.L.E. Headquarters and then placed in the laboratory where a team of experts would try to determine what had killed him. There was no more worry about that.

Solo was not too surprised that Mr. Waverly had decided to come along for the helicopter ride. The old warhorse was like that. Indeed, on many of Solo’s hazardous ventures for U.N.C.L.E. Mr. Waverly had shown up in the damnedest places at the damnedest times.

Looking at him now, in the Burgomeister’s office, Solo found it hard to believe that the old man was as stonily impatient with him as he eternally seemed. Waverly always made him feel like a pet student who had somehow failed to get 100 on a written examination in Strategy despite all of Waverly’s sound teachings. Jerry Terry had gone to see about the Debonair, dependent on the outcome of Solo’s interview with his Chief. Oberteisendorf, of course, was agog, having seen little activity since the days when armored task forces had roared through the town.

Now, aircraft had thundered overhead and officials of that big powerful country the United States were everywhere in evidence. Something to do with that American, the Herr Fromes, who had fallen down dead only two days ago—

“Well, Solo. I’m sure you have much to report. “Where should I start, Mr. Waverly?”

“Genesis, Solo. Even the Bible began there.”

Solo told all he had to tell, dating from the time of his encounter with Denise Fairmount and the infernal maser device. He was certain Waverly knew all about that, but he had to be thorough. He spent some time on Stewart Fromes’ peculiar condition of death as well as apparel.

When he came to the matter of the small silver pellet, Solo explained that all he could tell him about it was on the negative side. “It’s not a toxic substance, and it isn’t radioactive. According to all I’ve been able to discover in the short time I’ve been able to devote to it, it seems to be harmless. However, there’s undoubtedly more here than meets the eye—or the Geiger counter. A matter for the laboratory, I’d say.”

The old man, nodding as if to himself, took the pellet and tucked it carefully into the pocket of his vest. His baggy, wrinkled tweeds and thoughtful frown matched perfectly. This time, however, he seemed to have left his pipes behind in New York.

“You could fill me in a little, Mr. Waverly.”

“Yes, I suppose I could. But before we return to Fromes’ curious case, I would like to tell you that the Fairmount woman is definitely a Thrush agent. Our file on her is most extensive. Oddly enough, Fairmount is her real name. She uses it on special occasions. It is interesting that they wanted to sacrifice her when they employed the maser device. I must confess to no surprise at its existence. It has been employed once before, against an Israeli scientist. The poor fellow was driven out of his mind. But I don’t think they have managed yet to lick the problem altogether. There seem to be a few bugs in the thing, still.”

Solo nodded. “Then you don’t imagine Thrush has worked it into a large-scale weapon?”

Waverly pursed his lips. “Time enough for that later on, but no, I do not think so. We seem to have other secret weapons to think about at this time, Solo.”

“And Denise Fairmount?”

“She was not at the hotel when investigators arrived. For your information, she is a ranking Colonel in Thrush circles. Thanks to her beauty, her value has been considerable for Thrush. She also seems to be a brilliant young lady.”

Solo’s smile was tinged with bitterness.

“I should have killed her, then. I had her in the palm of my hand.”

Waverly shrugged. “Forget her for a time. Let us now discuss what you have just placed in the palm of my hand.”

Solo was more than willing to forget the subject of Denise Fairmount.

“What I handed you—that little silver gizmo—that could be a Booby Trap for Booby Troops.”

Waverly shook his head, smiling. “Nothing so romantic or so simple, I’m afraid. You see, Solo, I don’t know how much you’ve learned on this assignment as relates to Fromes, but you did know why we sent him here in the first place. I’m sure your friend Kuryakin gave you some clues.”

Solo nodded. “Yes, I remember. There was some idea of a powerful drug or some such that crippled whole populations, and the organization had somehow imagined that Oberteisendorf might be the next testing ground. Am I correct?”

“Partly. I’ll take you back a bit. The obscure village of Utangaville and a Scottish whistle stop called Spayerwood. Last year—two months apart—one day all the people in both those tiny spots turned into completely mindless creatures. Utangaville was first, then Spayerwood. The people were incapable of speech or coherent, coordinated action. It was quite as if they had been transformed into gibbering idiots. Both towns literally died—everyone in Utangaville was dead within two days, and in Spayerwood it all happened overnight. There were three hundred and fifty natives in Utangaville. Spayerwood was practically a hamlet—ninety-seven adults and twenty-seven children. The smaller number of people there may partially account for the shorter time-period.

“It wasn’t determined exactly what caused their deaths. All sorts of notions were formed, of course. Mysterious virus, some epidemic—a plague of some kind. Yet there was nothing conclusive. The situation has not reoccurred, and everyone has breathed a trifle easier. But—” He paused meaningfully.

“You expect it to happen again.”

“Decidedly. It has the mark of Thrush written all over it. For one thing, the markedly shorter amount of time it took to finish off Spayerwood—it couldn’t have been just because there were fewer people. I’m afraid it sounds like some organization has been experimenting with and improving its methods of killing whole populations.”

“Thrush, then,” said Solo.

Waverly nodded. “Yes. And judging from the state of Fromes’ body, they seem to be continuing their research.” He paused. “Anyway, Fromes uncovered something in the lab. I’m not familiar with the terms but he claimed there was some pointed similarity between Utangaville, Spayerwood and Oberteisendorf which made him insist the trail led here. I saw no harm in assigning a fine man and excellent chemist to follow a hunch, as it were. I’m sorry it turned out this way but I’m quite certain Fromes was correct. Otherwise he would not be dead.”

“With his clothes turned backwards.” Solo sighed. “I hope the silver ball means something.”

“It does and it will. Depend on it, Solo.”

He drew out his cigarettes and extended one to Waverly without thinking. The old man demurred and Solo shook his head.

“I am tired. I forgot the pipe routine.”

“What do you think about this rearrangement of clothing, Solo?”

“Two things, sir. I’m positive Fromes did it as a message. He was leaving a calling card for us after death.”

Waverly’s eyes narrowed. “Odd you should jump to that conclusion. Wouldn’t it have been simpler to leave a written message in code or some such?”

“No good, sir. Thrush would have seen it, and would have understood it sooner or later. No, he was leaving something only we would comprehend. Don’t you see? It adds up. If what you say about this drug or whatever it is is true, maybe there was no time for anything else. Maybe his last conscious act was to reverse his clothing while he was dying.”

Waverly shrugged.

“You may have it, my boy. I’m not sure I can disagree with you.”

Sunlight was streaming through Herr Muller’s windows. Waverly blinked against the light. He looked at his watch.

“Takeoff in fifteen minutes. Well, Solo, here are your new instructions. I will return to New York with the body. The Air Force is most obliging. You will return to Paris with Miss Terry. You have wings, I understand. As soon as you settle down somewhere—may I suggest you avoid the Hotel Internationale this trip—call me and I’ll let you know what we have learned about Fromes.”

“You trust Miss Terry?”

“Dear boy, we must. She is all that she says she is.” Waverly stood. “Clear now, as to what is to be done?”

“All the way down the line. By the way, did you ever hear of a fairly large cemetery in this vicinity? Place called Orangeberg. Seems to be quite famous around these parts.”

Waverly frowned. “Can’t say that I have. Why do you ask?”

“Herr Muller, the Burgomeister, seemed pretty keen on my burying Stewart Fromes’ body there.”

“A kindness, perhaps. Never be too suspicious of everyone. It could be a bad habit to develop. You will lose your perspective.”

“Could be. I’m not so sure in this case.”

“You should think more, Solo, of why even a town of this size makes it difficult for you to keep a body preserved. Something strange there. But nothing to worry about now.”

“No,” Solo said. “Thanks to you.”

Waverly glanced at his watch again. “I should say it was time I was joining the Air Force. Goodbye, Solo. See you in New York.”

“Goodbye, Mr. Waverly.”

Napoleon Solo stood where he was for a full five minutes after Waverly had gone. An idea had kindled in his head, only to flicker out again. It was annoying. He was certain that it had had something to do with Stewart Fromes having his clothes on backwards. Those clothes had to mean something.

Repressing his disgust, he went out to see about the plane and Jerry Terry.

They stood at the end of the meadow, watching the shining helicopter climb out of sight. The roar of its passage overhead whipped the knee-high stalks at the end of the field into a leaning pattern of graceful design.

Jerry Terry squinted in the sunlight of a warm, balmy afternoon.

“Hey, Solo,” she said. “Want to go for an airplane ride?”

“I’m with you, Miss Terry. Can you fly one of these things as well as warm it up?”‘

“Try me. You could use the rest.”

The cabin was sleek, smooth and familiar. Like an old friend. Solo locked the door on his side and settled back. His face wore a frown, however.

“What’s the matter with you today, lover? You look blue.”

“I’m just surprised we got out of town without any shooting going on. I usually have to blast my way out of places like Ye Olde Oberteisendorf.” He indicated the throng of curious townspeople and children crowding the edge of the meadow.

She batted the ignition switch on the instrument panel. “Forget it. My uncle is bigger than your U.N.C.L.E.”

“Come again?”

“Uncle Sam, Solo. They all know we’re represented by the biggest country in the world and they’re impressed. Besides, the last bit of excitement around here must have been V-E Day.”

“Maybe you’re right. But look at Herr Muller and the mortician. They sure do look sorry to see us go.”

It was true. The thin little Herr Burgomeister was positively crestfallen and the mortician reflected the same attitude. But the Debonair’s motor was purring powerfully, the propeller churning briskly. Jerry Terry fiddled with the control. board.

“Say goodbye to Oberteisendorf,” she suggested.

“Goodbye to Oberteisendorf.”

Within seconds, it was all behind them. The meadow, the startled faces, the huddled ugly town. The Bavarian Alps raised snowy heads on the Eastern horizon. Jerry banked the Debonair in a gradual, even soar of speed and finally leveled off at four thousand feet. Solo stared straight ahead, thoughtfully. The sky was a floor of unbroken blue on which the Debonair skirted gracefully.

“You’re still worried, Napoleon. Why?”

He sighed in exasperation. “I wish I knew why. Ever get the feeling you’re leaving something behind. Like unfinished business or something you had to do but you didn’t.”

“You feel that way now?”

“Very much so. I feel the last thing in the world we should be doing is saying goodbye to that ugly little town. And I don’t know exactly why.”

She flung him a look, saw the worry in his eyes. Her bright expression softened.

“Maybe we should take a look at—”

He sat up in his seat. “Of course. Though what good it will do, I don’t know. See if you can find that cemetery from the air. You may have to backtrack a bit but it ought to stand out on a day as nice as this. We can’t be too far from it, either.”

At his word, she had nosed the ship in a climbing turn, arrowing back in the direction they had come. Solo peered through the plexiglass, straining for the ground below. The earth from the air was a wide unending carpet, broken into terraced squares and oblongs and rectangles of all sizes and colors.

It was a mere five minutes before he saw the cemetery.

“There!” A flat expanse of earth, broken only by neat, orderly rows of stone markers.

“I’ll lower down. Hang on.”

The Debonair dropped like an elevator. Solo hung on, the sinking sensation in his stomach suddenly exhilarating like a roller coaster ride.

She cut her flying speed and arced the plane in a sweeping glide. The tiny squares of stone drew nearer with dizzying speed as the earth rushed up to meet them.

She leveled off, the Debonair skipping across the cemetery, yards above the earth. Solo scanned the tableau.

It was a beautiful place. Tended green landscape, flowers still in evidence. The whole area looked well cared for and arranged by a master landscape artist. That was all there was time for. The plane climbed, avoiding the wall of trees just ahead. Jerry sniffed the air.

“Cozy. Another look?”

“One more, maybe, though I don’t know what the hell I’m looking for.”

On the second pass, Solo tried to estimate the number of headstones. But the ground roared by and they were aloft again.

“Herr Muller was right. A lovely spot.”

“Orangeberg. Nice name somehow.”

“Yes.” He was still trying to think of that elusive thing that was dancing around in his brain, but it was useless. He was weary and so was his mind. “I made out about two hundred headstones. Muller said there were that many at least—

“I never flew over a cemetery before.”

“You’re likely to do lots of things you never did before, on this assignment.”

She laughed. “Paris, next?”

“Non-stop, if you please.”

The cemetery of Orangeberg moved away from them as they rose to the West. The sun was now a blinding red ball in the sky—and neither of them saw the whining black shadow which dropped from behind its concealing corona of blaze.

The dark shadow power-dived and fastened itself on their tail with deadly intent

The next sound either Napoleon and Jerry Terry heard was the thudding, frenzied pound of .50 calibre machine-gun fire slamming into the wings of the Beechcraft Debonair.