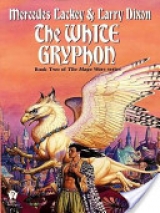

Текст книги " The White Gryphon"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Соавторы: Ларри Диксон

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

He nodded, slowly. "I understand. So the question becomes, how do we persuade others over to our side?"

She shook her head, and her jewelry sang softly. "Gentle persistence. It helps that you have Skandranon with you; he is such a novelty that he is keeping peoples' minds off what you folk truly represent. I was accepted because what I amfell within the bounds of what they had already accepted. You must tread a careful path, Amberdrake. You dare not give offense, or give reason for the Haighlei to dismiss you as mere barbarians."

"What else do we need to know?" Winterhart asked urgently.

"Mostly that the Haighlei are very literal people; they will tell you exactlywhat they mean to do, not a bit more, and not a bit less." She creased her brow in thought. "Of course, that is subject to modification, depending on how the person feels about you. If you asked one who felt indifferent toward you to guard your pet, he would guard your pet and ignore the thief taking your purse."

Amberdrake nodded, trying to absorb it all.

"What can you tell us about this Eclipse Ceremony?" he asked.

Silver Veil smiled.

"Well," she said, with another wave of her fan, "Obviously, it begins, ends, and centers around the Eclipse...."

Zhaneel found the hot afternoons as soporific as any of the Haighlei, and usually followed their example in taking a long nap. Even the youngsters were inclined to sleep in the heat—her Tadrith and Keenath and Winterhart's energetic girl Windsong. Well, since the twins had been born, shehad been short on sleep, so now she might have a chance to make it up at last. Let Skandranon poke his beak in and around the corners of this fascinating Palace; while it was this hot, shewould luxuriate in a nest of silken cushions, or stretch her entire length along a slab of cool marble in the garden.

She was doing just that, when one of the servants entered, apparently unaware of her presence. The twins were asleep in the shade, curled up like a pair of fuzzy kittens beside one of the pools, for they liked to use the waterfall as a kind of lullaby. The servant spotted them and approached them curiously, then reached out a cautious hand to touch.

Not a good idea, since the little ones sometimes woke when startled in an instinctive defensive reaction. An unwary human could end up with a hand full of talons, which would be very painful, since each of the twins sported claws as formidable as an eagle's. She raised her head and cleared her throat discreetly.

The servant started, jerking upright, and stared at her for a single, shocked second, with the whites of his eyes showing all around the dark irises. Then he began to back up slowly, stammering something in his own language. She couldn't understand him, of course, but she had a good idea of the gist of it, since this wasn't the first time she'd startled a servant.

Nice kitty. Good kitty. Don't eat me, kitty—

She uttered one of the few phrases in his language she knew, the equivalent of "Don't be afraid, I didn't know you were coming in; please don't wake the babies."

He stared at her in shock, and she added another of the phrases she'd learned. "I prefer not to eat anything that can speak back to me."

He uttered something very like a squeak, and bolted.

She sighed and put her head down on her foreclaws again. Poor silly man. Doesn't anyonetell these people about us?It wasn't that the Haighlei were prejudiced, exactly, it was just that they wereused to seeing large, fierce, carnivorous creatures, but were notused to them being intelligent. Sooner or later she and Skan would convince them all that the gryphons were neither dangerous, nor unpredictable, but until they did, there would probably be a great many frightened servants setting new records for speed in exiting a room.

Those who accept us as intelligent are still having difficulty accepting us as full citizens, co-equal with the humans of White Gryphon,she reflected, wondering how they were going to overcome that much stickier problem. At least I don't have to worry about that. Skan does, but I don't. All I have to do is be charming and attractive. And the old rogue says I have no trouble doing that! Still, he has to do that himself, plus he has to play "Skandranon, King of White Gryphon."

The sound of someone elsediscreetly clearing her throat made Zhaneel raise her head again, wondering if she was ever going to get that nap.

But when she saw who it was, she was willing to do without the nap. "Makke!" she exclaimed, as the old, stooped human made her way carefully into the garden. "Can it be you actually have nothing to do? Can I tempt you to come sit in the garden?"

Makke was very old, and Zhaneel wondered why she still worked; her closely-cropped hair resembled a sheep's pelt, it was so white, and her back was bent with the weight of years and all the physical labor she had done in those years. Her black face was seamed with wrinkles and her hands bony with age, but she was still strong and incredibly alert. Zhaneel had first learned that Makke knew their language when the old woman asked her, in the politest of accented tones, if the young gryphlets would require any special toilet facilities or linens. Since then, although her assigned function was only to clean their rooms and do their laundry, Makke had been Gesten's invaluable resource. She adored the gryphlets, who adored her in return; she was often the only one who could make them sit still and listen for any length of time. Both Zhaneel and Gesten were of one accord that in Makke they had made a good friend in a strange place.

"I really should not," the old woman began reluctantly, although it was clear she could use a rest. "There is much work yet to be done. I came only to ask of you a question."

"But you should, Makke," Zhaneel coaxed. "I have more need of company than I have of having the floors swept for the third time this afternoon. I want to know more about the situation here, and how we can avoid trouble."

Makke made a little gesture of protest. "But the young ones," she said. "The feather-sheath fragments, everywhere—"

"And they will shed more as soon as you sweep up," Zhaneel told her firmly. "A little white dust can wait for now. Come sit, and be cool. It is too hot to work. Everyone else in the Palace is having a nap or a rest."

Makke allowed herself to be persuaded and joined Zhaneel, sitting on the cool marble rim of the pond. She sighed as she picked up a fan and used it to waft air toward her face. "I came to tell you, Gryphon Lady, that you have frightened another gardener. He swears that you leaped up at him out of the bushes, snarling fiercely. He ran off, and he says that he will not serve you unless you remain out of the garden while he works there."

"He is the one who entered while I was already here." Zhaneel snorted. " Youwere in the next room, Makke," she continued in a sharp retort. "Did you hear any snarling? Any leaping? Anything other than a fool fearing his shadow and running away?"

Makke laughed softly, her eyes disappearing into the wrinkles as she chuckled. "No, Gryphon Lady. I had thought there was something wrong with this tale. I shall say so when the Overseer asks."

Zhaneel and Makke sat quietly in easy silence, listening to the water trickle down the tiny waterfall. " Youought to be the Overseer," Zhaneel said, finally. "You know our language, and you know more about the other servants than the Overseer does. You know how to show people that we are not man-eating monsters. You are better at the Overseer's job than he is."

But Makke only shook her head at the very idea, and used her free hand to smooth down the saffron tunic and orange trews that were the uniform for all Palace servants, her expression one of resignation. "That is not possible, Gryphon Lady," she replied. "The Overseer was born to his place, and I to mine, as it was decreed at our births. So it is, and so it must remain. You must not say such things to others. It will make them suspect you of impiety. I know better because I have served the Northern Kestra'chern Silver Veil, but others are not so broad of thought."

Zhaneel looked at her with her head tilted to one side in puzzlement. This was new. "Why?" she asked. "And why would I be impious for saying such a thing?"

Makke fanned herself for a moment as she thought over her answer. She liked to take her time before answering, to give the question all the attention she felt it deserved. Zhaneel did not urge her to speak, for she knew old Makke by now and knew better than to try to force her to say anything before she was ready.

"All is decreed," she said finally, tapping the edge of her fan on her chin. "The Emperors, those you call the Black Kings, are above all mortals, and the gods are above them. The gods have their places, their duties, and their rankings, and as above, so it must be below. Mortals have their places, duties, and castes, with the Emperors at the highest and the collectors of offal and the like at the lowest. As the gods do not change in their rankings, so mortals must not. Only the soul may change castes, for each of the gods was once a mortal who rose to godhood by good works and piety. One is born into a caste and a position, one works in it, and one dies in it. One can make every effort to learn—become something of a scholar even, but one will never be permitted to becomea Titled Scholar. Perhaps, if one is very diligent, one may rise from being the Palace cleaning woman for a minor noble to that of a cleaning woman to a Chief Advisor or to foreign dignitaries, but one will always be a cleaning woman."

"There is no change?" Zhaneel asked, her beak gaping open in surprise. This was entirely new to her, but it explained a great deal that had been inexplicable. "Never?"

Makke shook her round head. "Only if the Emperor declares it, and with him the Truthsayer and the Speaker to the Gods. You see, such change must be sanctioned by the gods before mortals may embrace it. When some skill or position, some craft or learning, is accepted from outside the Empire, it is brought in as a new caste and ranking, and remains as it was when it was adopted. Take—the kestra'chern. I am told that Amberdrake is a kestra'chern among your people?"

Zhaneel nodded proudly. "He is good! Very good. Perhaps as good or better than Silver Veil. He was friend to Urtho, the Mage of Silence." To her mind, there could be no higher praise.

"And yet he has no rank, he offers his services to whom he chooses, andhe is one of your envoys." Makke shook her head. "Such a thing would not be possible here. Kestra'chern are strictly ranked and classed according to talent, knowledge, and ability. Each rank may only perform certain services, and may only serve the noblesand noble households of a particular rank. No kestra'chern may offer his services to anyone above orbelow that rank for which he is authorized. This, so Silver Veil told me once, is precisely as the kestra'chern first served in the north, five hundred years ago, when the Murasa Emperor Shelass declared that they were to be taken into our land. I believe her, for she is wise and learned."

Zhaneel blinked. Such a thing would never have occurred to her, and she stored all of this away in her capacious memory to tell Skan later. No one can rise or fall? So where is the incentive to do a good job?

"We are ruled by our scribes in many ways," Makke continued, a little ruefully. "All must be documented, and each of us, even the lowest of farmers and street sweepers, is followed through his life by a sheaf of paper in some Imperial Scribe's possession. The higher one's rank, the more paper is created. The Emperor has an entire archive devoted only to him. But he was born to be Emperor, and he cannot abdicate. He was trained from birth, and he will die in the Imperial robes. As I will be a cleaning woman for all this life, even though I have studied as much as many of higher birth to satisfy my curiosity, so he will be Emperor."

"But what about the accumulation of wealth?" Zhaneel asked. "If you cannot rise in rank, surely you can earn enough to make life more luxurious?" That would be the only incentive that I can imagine for doing well in such a system.

But Makke shook her head again. "One may acquire wealth to a certain point, depending upon one's rank, but after that, it is useless to accumulate more. What one isdecrees what one may own; beyond a certain point, money is useless when one has all one is permitted by law to have. Once one has the home, the clothing, the possessions that one may own under law, what else is left? Luxurious food? The company of a skilled mekasathay? The hire of entertainers? Learning purely for the sake of learning? It is better to give the money to the temple, for this shows generosity, and the gods will permit one to be reborn into a higher rank if one shows virtues like generosity. I have given the temple many gifts of money, for besides dispensing books and teachers, the temple priests speak to the gods about one's virtue—all my gifts are recorded carefully, of course—and I will probably give the temple as many more gifts as I can while I am in this life."

Zhaneel could hardly keep her beak from gaping open. "This is astonishing to me," Zhaneel managed. "I can't imagine anyone I know living within such restrictions!"

Makke fanned herself and smiled slowly. "Perhaps they do not seem restrictive to us," she suggested.

"Makke?" Zhaneel added, suddenly concerned. "These things you tell me—is this forbidden, too?"

Makke sighed, but more with impatience than with weariness. "Technically, I could be punished for telling you these things in the waythat I have told you, and some of the other things I have imparted to you are pieces of information that people here do not talkabout, but I am old, and no one would punish an old woman for being blunt and speaking the truth." She laughed. "After all, that is one of the few advantages of age, is it not? Being able to speak one's mind? Likely, if anyone knowing your tongue overheard me, the observation would be that I am aged, infirm, and none too sound in my mind. And ifI were taken to task for my words, that is precisely what I would say." Makke's smile was wry. "There are those who believe my interest in books and scholarly chat betokens an unsound mind anyway."

"But this is outside of my understanding and experience. It will take me a while to think in this way. In the meantime, what must we do to keep from making any dreadful mistakes?" Zhaneel asked, bewildered by the complexity of bureaucracy that all this implied.

"Trust Silver Veil," Makke replied, leaning forward to emphasize her advice and gesturing emphatically with her fan. "She knew something of the Courts before she arrived here, and she has been here long enough to know where all the pit traps and deadfalls are. She can keep you from disaster, but what is better, she can keep you from embarrassment. Icannot do that. I do not know enough of the higher stations."

"Because we can probably avoid disaster, but we might miss a potential for embarrassment?" Zhaneel hazarded, and Makke nodded.

And in a society like this one, surely embarrassment could be as deadly to our cause as a real incident. Oh, these people are so strange!

"There is something else that I believe you must know," Makke continued. "And since we are alone, this is a good time to give you my warning. Something of what Gesten said makes me think that the Gryphon Lord is also a worker of magic?"

Zhaneel nodded; something in Makke's expression warned her not to do so too proudly. She looked troubled and now, for the first time, just a little fearful.

'Tell him—tell him he must notwork any magics, without the explicit sanction of King Shalaman or Palisar, the Speaker to the Gods," Makke said urgently but in a very soft voice, as she glanced around as if to be certain that they were alone in the garden. "Magic is—is strictly controlled by the Speakers, the priests, that is. The ability to work magic is from the hands of the gods, the knowledge of how to use it is from the teachers, and the knowledge of whento use it must be decreed by priest or Emperor."

Zhaneel clicked her beak. "How can that be?" she objected. "Mages are the most willful people I know!"

Makke only raised her eyebrows. "Easily. When a child is born with that ability, he is taken from his parents by the priests before he reaches the age of seven, and they are given a dower-portion to compensate them for the loss of a child. The priests raise him and train him, then, from the age of seven to eighteen, when they return to their families, honored priests and Scholars. I say 'he,' though they take female children as well, though females are released at sixteen, for they tend to apply themselves to study better than boys in the early years, and so come to the end of training sooner."

"That still doesn't explain how the priests can keep them under such control," Zhaneel retorted.

"Training," Makke said succinctly. "They are trained in the idea of obedience, so deeply in the first year that they never depart from it. This, I know, for my only daughter is a priest, and all was explained to me. That, in part, is why I was given leave to study and learn, so that I might understand her better when she returned to me. The children are watched carefully, more carefully than they guess. If one is found flawed in character, if he habitually lies, is a thief, or uses his powers without leave and to the harm of others, he is—" she hesitated, then clearly chose her words with care. "He is removed from the school and from magic. Completely."

A horrible thought flashed through Zhaneel's mind at the ominous sound of that. "Makke!" she exclaimed, giving voice to her suspicions, "You don't mean that they—they killhim, do you?"

"In the old days, they did," Makke replied solemnly. "Magic is a terrible power, and not for hands that are unclean. How could anyone, much less a priest, allow someone who was insane in that way to continue to move in society? But that was in the old days—now, the priests remove the ability to touch magic, then send the child back to his family." She shrugged. "It would be better for him, in some ways, if they didkill him."

"Why?" Zhaneel blurted, uncomprehendingly.

"Why, think, Gryphon Lady. He can no longer touch magic. He returns to his family in disgrace. Everyone knows that he is fatally flawed, so no one will trust him with anything of any consequence. No woman would wed him, with such a disgrace upon him. He will, when grown, be granted no position of authority within his rank. If his rank and caste are low, he will be permitted only the most menial of tasks within that caste, and only under strict supervision. If he comes from high estate, he will be an idle ornament, also watched closely." Makke shook her head dolefully. "I have seen one of that sort, and he was a miserable creature. It was a terrible disgrace to his family, and worse for him, for although he is a man grown, he is given no more responsibility than a babe in napkins. He is seldom seen, but the lowest servant is happier than he. He is of very high caste, too, so let me assure you that no child is immune from this if a flaw is discovered in him."

Zhaneel shook her head. "Isn't there anything that someone like that can do?"

Makke shrugged. "The best he could do would be to try to accumulate wealth to grant to the temple so that the gods will give him an incarnation with no such flaws in the next lifetime. It would be better to die, I think, for what is a man or a woman but their work, and how can one bea person without work?"

Zhaneel was not convinced, but she said nothing. At least the Black Kings certainly seemed to have a system designed to prevent any more monsters like Kiamvir Ma'ar! There was something to be said for that.

Almost anything that prevented such a madman from getting the kind of power Ma'ar had would be worth bearing with, I think. Almost. And assuming that the system is not fatally flawed.

"Have the priests ever—made a mistake?" she asked, suddenly.

"Have they ever singled out a child who was notflawed for this punishment, you mean?" Makke asked. Then she shook her head. "Not to my knowledge, and I have seen many children go to the temples over the years. Truly, I have never seen one rejected that was not well-rejected. This is not done lightly or often, you know. The one I spoke of? He has no compassion; he uses whomever he meets, with no care for their good or ill. Whilst his mother lived, he used even her for his own gain, manipulating her against her worthier offspring. There are many of lesser caste who have learned of his flawed nature to their sorrow or loss."

Zhaneel chewed a talon thoughtfully.

'There is one other thing," Makke said, this time in a softer and much more reluctant voice. "I had not intended to speak of this, but I believe now perhaps I must, for I see by your face that you find much of what I have said disturbing."

"And that is—?" Zhaneel asked.

Makke lowered her voice still further. "That there is a magic which is more forbidden than any other. I would say nothing of it, except that I fear your people may treat it with great casualness, and if you revealed that, there would be no treaty, not now, and not in the future. Have your people the magic that—that looks into—into minds—and hears the thoughts of others?"

"It might be," Zhaneel said with delicate caution, suddenly now as alert as ever she had been on a scouting mission. All of her hackles prickled as they threatened to rise. There was something odd about that question. "I am not altogether certain what you mean, for I believe our definitions of magic and yours are not quite the same. Why do you ask?"

"Because thatis the magic that is absolutely forbidden to all except the priests, and only then, the priests who are called to special duties by the gods," Makke said firmly. "I do not exaggerate. This is most important."

"Like Leyuet?" Zhaneel asked in surprise. She had not guessed that Truthsayer Leyuet was a priest of any kind. He did not have the look of one, nor did he wear the same kind of clothing as Palisar.

"Yes." Makke turned to look into her eyes and hold her gaze there for a long moment, with the same expression that a human mother would have in admonishing a child she suspects might try something stupid. "This magic is a horror. It is unclean," she said, with absolute conviction. "It allows mortals to look into a place where only the gods should look. Even a Truthsayer looks no farther than to determine the veracity of what is said—only into the soul, which has no words, and not the mind. If your people have it, say nothing. And do notuse it here."

We had better not mention Kechara, ever, to one of these people! And Amberdrake had better be discreet about his own powers!

That was all she could think at just that moment. While Zhaneel tried to digest everything she'd been told, Makke stood, and carefully put the palm fan on the small pile left for the use of visitors. "I must go," she said apologetically. "A certain amount of rest is permitted to one my age, but the work remains to be done, and I would not trust it to the hands of those like that foolish gardener, who would probably think that Jewel and Corvi wish to rend him with their fearsome claws."

Since neither Jewel nor Corvi had anything more than a set of stubby, carefully filed down nails, Zhaneel laughed. Makke smiled and shuffled her way back into their suite.

The gryphlets looked ready to sleep for the rest of the afternoon; not even all that talking disturbed them in the least. Zhaneel settled herself on a new, cooler spot, and lay down again, letting the stone pull some of the dreadful heat out of her body.

She closed her eyes, but sleep had deserted her for the moment. So Makke is an untitled Scholar! No wonder she looks as if she were hiding secrets.Now, more than ever, Zhaneel was glad that she and Gesten had made friends with the old woman. Next to the Silver Veil, it seemed they could not have picked a better informant. That explains why she bothered to learn our language, anyway. She must have been very curious about Silver Veil and the north, and the best way to find out would have been to ask Silver Veil. It must have taken a lot of courage to dare that, though.

But Makke was observant; perhaps she had noticed how kind Silver Veil was to her servants, and had decided that the kestra'chern would not take a few questions amiss.

An amateur scholar would also have been fascinated by the gryphons and the hertasi.Perhaps that was why Makke had responded to the overtures of friendship Zhaneel and Gesten had made toward her.

And when it became painfully evident how naive we were about the Haighlei—Zhaneel smiled to herself. There was a great deal of the maternal in Makke's demeanor toward Zhaneel, and there was no doubt that she thought the twins were utterly adorable, even if they looked nothing like a pair of human babies. Perhaps Makke had decided to adopt them, as a kind of honorary grandmother.

She said, onlydaughter. She could have meant only child as well. And if her child is now a priest—do the Haighlei allow their priests to marry and have children? I don't think so.Zhaneel sighed. Iwonder if her daughter is ashamed of Makke; she is only a cleaning woman, after all. For all that most priests preach humility, I never have seen one who particularly enjoyed being humble.If that were the case, Makke could be looking on Zhaneel as a kind of quasi-daughter, too.

I shall have to make certain to ask her advice on the twins. I don't have totake it, after all! And that will make her feel wanted and needed.Zhaneel sighed, and turned so that her left flank was on the cool marble. But the warning about magic– that is very disturbing. Except, of course, that we can't do much magic until the effect of the Cataclysm settles. That might not even be within our lifetimes.

She would warn Skandranon, of course. And he would warn Amberdrake. Zhaneel was not certain how much of what Amberdrake did was magic of the mind, and how much was training and observation, but it would be a good thing for Drake to be very careful at this point. Winterhart, too, although her abilities could not possibly be as strong as Drake's....

Healing. I shall have to ask Makke about Healing. Surely the Haighlei do not forbidthat !

But the one thing they must not mention was the existence of Kechara. If the Haighlei were against the simpler versions of thought-reading, surely they would be horrified by poor little Kechara!

The fact that she is as simple-minded as she is would probably only revolt them further. And sheis misborn; there is no getting around that. It's nothing short of a miracle that she has had as long and as healthy a life as she has. But she is not "normal" and we can't deny that.

So it was better not to say anything about her. It wasn't likely that anyone would ask, after all.

Let me think, though– they may ask how we are communicating so quickly with White Gryphon. So– this evening, Skan should ask permission from King Shalaman and Palisar to "communicate magically" with the rest of the Council back home. Sincethey do that, they shouldn't give Skan any problems about doing the same. He's clever; if they ask him how he can communicate when things are so magically unsettled, he can tell them about the messages we send with birds, or tell them something else that they'll believe, and not be lying. Then, when we get instant answers from home, they won't be surprisedor upset because we didn't ask permission first.

So that much was settled. If the Haighlei sent resident envoys to White Gryphon, there was no reason to tell them what Kechara was—

And since she is there among all the other children of the Silvers, her room just looks like a big nursery. Would they want to talk to her, though?

Would an envoy have any reason to talk to anychild, except to pat it on the head because its parents were important? Probably not. And Cafri could keep her from bounding over and babbling everything to the envoys; he'd kept her from stepping on her own wings before this.

With all of that sorted out to Zhaneel's satisfaction, she finally felt sleep overcoming her. She made a little mental "tag" to remind her to tell Skan all about this conversation and the things she'd reasoned out, though. Gryphonic memory was excellent, but she wanted to make certain that nothing drove thisout of her mind, even on a temporary basis.

Then, with her body finally cooled enough by the stone to relax, she stretched out just a little farther and drifted off into flower-scented dreams.