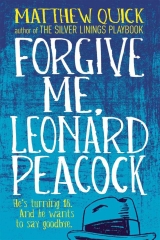

Текст книги "Forgive me, Leonard Peacock"

Автор книги: Matthew Quick

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

THIRTY-SIX

I hear the TV blaring.

Walt sometimes has trouble hearing, so I’m not surprised by the volume.

What surprises me is this: He’s watching Bogart films this early in the morning.

I hear Katharine Hepburn’s uppity voice and know he’s watching The African Queen again.

“HELLO?” I say as loud as possible as I walk under the chandelier.

Walt doesn’t answer, and when he sees me standing in the room’s entranceway, he sort of jumps in his recliner, looks at me for a few seconds, turns off the movie with the remote, and says, “Leonard?”

“It’s me. In the flesh.”

“I couldn’t sleep. Been watching Bogie all night. I was really worried about you. I thought that—I called your home, but no one answered and—”

We just look at each other for a long time because he doesn’t want to say what he’s thinking and I don’t want to talk about last night.

Finally, he regains his composure, falls back into the safety of our routine, picks up his Bogart hat off the arm of his recliner, pops it onto his head, and pulls his old-time movie-star face.[69]69

It’s funny because we never used Bogart hats before yesterday, but somehow I understand that his putting the hat on is symbolic—a sign that we are about to talk in code. Walt and I have something going on that’s hard to explain. We understand each other. We just do. And I love that so much. Good-guy pheromones.

[Закрыть]

“Is something the matter, Mr. Allnut? Tell me,” he says, his jaw barely moving, his voice higher than natural, playing Rose Sayer, Katharine Hepburn’s character in The African Queen.

I adjust my Bogart hat—even though Bogie doesn’t wear this type of hat in this movie—and say, “Nothing. Nothing you’d understand.”

“I simply can’t imagine what could be the matter. It’s been such a pleasant day. What is it?” he says, staying in character.

But suddenly, I don’t really want to trade Bogart movie quotes anymore, so I take off my hat and, using my regular speaking voice, I say, “Yesterday was bad, Walt. Really terrible.”

His eyes open so wide. “What the hell happened to your hair?”

Words escape me—I mean, how would I even begin to explain it all to the old man?

In an effort to avoid eye contact, I stare at the picture of Walt’s dead wife, who hangs eternally young on the wall.

Sea-foam green blouse.

Blond Bogart-era hairstyle.

Mysterious eyes that pop and seem to be watching me.

She doesn’t look much older than eighteen in the photo but she’s dead now. I know Walt misses her terribly because I catch him gazing at the picture with this sad look in his eyes. I wonder what my future wife will look like and if I’ll hang her picture on my wall—maybe in Lighthouse 1.

“And what’s with the goofy medal on your shirt?”

Walt’s staring at my heart now. His eyebrows are zigzags.

I look down and remember Herr Silverman’s creation. I’m not sure I can explain the significance of the medal without getting into all the bullshit I went through last night, so I say, “I know I acted strange yesterday. I’m sorry. And I’ll tell you everything you want to know later, Walt. I swear to god. I’ll answer every question you got. But for now, could we just watch the rest of the movie together wearing our Bogart hats? Can we do that? It would mean a lot to me if you just let me watch the movie with you. I’m really tired. I don’t have much left in the proverbial tank. It was a hell of a night. It really was. I need some Bogart. Bogie medicine. Whadda ya say?”

He looks at me for a second or two—examines my face, trying to figure my angle out—and then says, “Sure. Sure. Bogart. We can do that,” real cautiously, like maybe he thinks I’m trying to trick him, even though I’m being utterly sincere and honest—maybe for the first time in years.

I put my Bogart hat back on and sit down at the end of the couch closest to his recliner.

He hits play on his remote and the picture on the TV comes to life.

It’s the part where their boat gets stuck in mud, and when Bogart tries to free it by getting into the water, he returns covered in leeches. Since they’re stuck in the middle of nowhere, they think they’re going to die. But Rose prays and it starts to rain and the river rises and they’re miraculously saved. A whole bunch of other stuff happens with evil Germans, which I already know. My eyes glaze over and I zone out, mostly thinking about how close I came to killing Asher and myself last night. How it almost seemed like I was watching a movie when I had the gun pointed at my classmate—like it wasn’t even real. How fucked-up scary that seems now that my head is straight. As I sit here next to Walt, I feel kind of grateful for this moment, as strange as that sounds—like I just narrowly avoided some awful, demented fate.

I feel kind of lucky.

It worries me that I can be so explosive one day—volatile enough to commit a murder-suicide—and then the next day I’m watching Bogart save the day with Walt, like nothing happened at all, and nothing is urgent, and I really don’t have to do anything to set the world right or escape my own mind.

I’d like to feel okay all the time—to have the ability to sit and function without feeling so much pressure, without feeling as though blood is going to spurt from my eyes and fingers and toes if I don’t do something.

When the movie ends, Walt clicks off the TV and says, “You know, I was thinking.”

“And?” I say.

“Why did you give me this hat yesterday? I mean, what was so special about yesterday?”

“It was my birthday. I turned eighteen.”

“Jesus Christ! Why didn’t you tell anybody? I feel like a cheapskate now. I would’ve bought you a present.”

I smile and say, “I bought your hat at the thrift store for four dollars and fifty cents. It’s not really an old movie prop. Bogie never wore it.”

“Yeah, I know, Rockefeller,” he says. “I like it anyway. So what did you do to celebrate your birthday?”

I almost laugh, because Walt asked the question so innocently, like I’m just a regular kid who had a regular birthday.

Walt’s the only person in the world who would think I’m capable of being regular like that, and I kind of love him for it.

“Can I tell you what happened to me on my birthday later? I’m still kind of tired. And I don’t feel like talking about it right now.”

Walt looks at me a second, takes off his Bogart hat, and then says, “Lauren Bacall approaching Bogart at the bar in The Big Sleep,” and then in a girlish, husky Bacall voice he says, “I’m late. I’m sorry.”

I remember the scene and the lines, so playing Bogart I say, “How are you today?”

“Better than last night.”

“Well, I can agree on that,” I say.

“That’s a start,” he says, breaking character. “That’s a start.”

I force a smile, but it’s awkward and Walt knows it.

Am I better than last night?

I dunno.

But I don’t feel angry anymore.

“You going to school today?” Walt says, just before the silence gets strange.

“I’m thinking I’ll take the day off. And I have to go home now. I haven’t been home since yesterday. I need a shower,” I say, even though I don’t really give a shit about taking a shower. “Movie later tonight?”

He flips open his Zippo with his thumb—making that scrappy clink noise—lights up a cigarette, takes a pull, and exhales his smoky words. “Sounds like the start of a beautiful friendship, Leonard. It really does.”

“Here’s looking at you, kid.”

He smiles in this really good, honest way—better than Bogie even.

I take it in and, when our smiling at each other starts to feel too awkward, I turn and walk away.

“Leonard?”

I spin around to face Walt.

“I’m glad you visited me this morning.”

As he blows another lungful of smoke at the ceiling, his eyes twinkle under his Bogart hat brighter than the orange cherry on his Pall Mall, and I get the sense that even though we just watch old Bogart movies together and never really talk about anything but Bogie-related topics, maybe Walt knows me better than anyone else in the world, as strange as that sounds. Maybe we’ve been communicating effectively through Bogart-related quotes all along. Maybe I’m better than I thought when it comes to communication, at least with people like Walt.

And maybe there are other people like Walt out there—waiting for me to find them.

Maybe.

THIRTY-SEVEN

The kitchen mirror in my house is still in pieces, so when I look into the sink a million little jagged minnows return my stare.

I open the fridge and see my hair wrapped in pink paper, and I think, What the fuck? and Who was I yesterday? and What the fuck? again.

I should clean it all up, but I simply don’t have the strength.

It’s so much easier to shut the refrigerator door, which is totally a metaphor, I realize, for my life.

Maybe I want Linda to find the wrapped-up hair and see it all—how horrible I was yesterday.

What a shitty birthday I had.

That she forgot she gave birth to me eighteen years ago.

That she is the worst mother in the world.

How much help I need.

But Linda probably wouldn’t make the connection even if she found my hair wrapped in pink paper. She’d probably think I cut my hair as a present for her.

I make my way upstairs to my bedroom.

When I empty my pockets I realize that my cell phone ran out of power some point after I left Herr Silverman’s apartment, so I plug it in.

After it loads up, the you-have-messages signal buzzes.

There’s a voice mail from Linda, who says, “What did you tell your teacher about me? What’s going on? What is it this time? I’m in the back of a car on my way home instead of attending the several extremely important meetings I had planned. What the hell is going—”

I delete before she can finish.

Then there’s a message from Herr Silverman and his voice sounds different, sort of pissed. “Leonard? Why did you leave? Where did you go? I’m worried about you. I took a risk last night and I have to say I’m disappointed in you. You shouldn’t have left. You’ve put me in an awkward position, because I promised your mother that—”

For some reason I delete him too.

Then I feel guilty and call him back, even though he’s probably in school by now, because it’s later than I thought.

The phone rings and rings and finally I get his voice mail.

“It’s me. Leonard Peacock. Thanks for coming to the bridge last night. That was really cool . . . necessary, even. I’m sorry I got you in trouble with your partner. I’m sorry I’ve been such an asshole. I’m going to do the work. Don’t worry about me. I just had a bad night. I’ll be okay. But I’m taking a day off. I just had to leave this morning. Just got the urge to move. Had to greet the day, if you know what I mean. I hope your partner didn’t think I was rude. I won’t tell anyone that you’re gay. I don’t care that you’re gay. It doesn’t matter to me. That was probably a stupid thing to say, right? Because why should I care? I’d never say I don’t care that you’re black to a person of color. I’m an asshole. Sorry. Just forget about that part. See you Monday. Thanks again. And don’t worry about me! There’s nothing to worry about anymore. Nothing.” Then I just sort of hold the phone to my ear without hanging up. I listen to silence for a minute, thinking that all of what I said was just plain idiotic, and then there is a beep and this robot woman comes on and asks if I’m satisfied with my message. I don’t have the strength to answer that honestly, let alone record another, so I just hang up.

It’s so quiet in my room that I wonder if this is what being dead sounds like.

I hear Linda key into the front door and then she’s yelling, “Leo? Leo, are you here? Why didn’t you call me back?”

I hate her.

I hate her so much.

She’s so stupid it’s almost comical.

She’s such a caricature.

Such a nonperson.

What type of mother forgets her son’s eighteenth birthday?

What type of mother ignores so many warning signs?

It’s almost impossible to believe she exists.

I hear her high heels click across the hardwood floor and then I hear silence as she stops by the hallway mirror to check her makeup. No matter what Herr Silverman told her, no matter how much he sugarcoated it, whatever he said was enough to get her to drive all the way here from New York City. So you’d think she’d run up the stairs to make sure I’m okay, right? Like any rational, caring mother would. Like any HUMAN would. But you’d be wrong.

Linda can’t pass a mirror without pausing because she’s addicted to mirrors, so don’t judge her too harshly. She has issues. It doesn’t even piss me off, because that’s just Linda. I could be on fire, screaming my head off, and she’d still have to pause in front of the mirror to check her makeup before she could extinguish me. That’s my mom.

More clicking of high heels and then she’s walking up the steps, which has a runner of carpet so no clicking.

“Leo?” she says joyfully, like she’s singing, and I wonder if she’s singing because she’s hoping I’m not here—like maybe she hopes I offed myself and she’ll never have to deal with me again. “Leo, where are you?”

More clicking as she walks down the hallway, then silence as she crosses the Oriental runner that leads to my bedroom.

“Leo?” she says, and then knocks.

I stare at the door so hard, thinking of how justified I’d be if I just went off on her, listing all the ways that she’s failed me, but I can’t bring myself to say anything.

“Leo?” Linda says. “I hope you are decent. I’m coming in.”

She pushes the door open and there she is in my bedroom doorframe. She’s wearing a white jacket with some sort of fur collar—it looks like mink. Her hair is perfect as always. She’s got on a knee-length bright green wool skirt—classy and age-appropriate—and white heels. She looks amazing, as always. And it makes me laugh because her appearance suggests she’d have the perfect son—like she lives a perfect life and therefore has all the time in the world to make herself into a masterpiece of high fashion every day. People see Linda and they admire her. It’s true. You would too, if you saw her. And that’s her power.

“I’m happy you finally cut your hair, but who cut it? They did a terrible job, Leo,” she says, and I want to strangle her. “What’s going on with you? What’s this all about? I’m here. I’m home. Now what seems to be the problem?”

I shake my head, because even I’m amazed.

What the hell am I supposed to say to that?

“I spoke with your teacher, Mr. Silverman. He was a bit dramatic. He said you had your grandfather’s old war gun. As if that paperweight would ever fire, I told him. Well, you fooled him with your prank, because he was really concerned, Leo. Enough to insist I come home from New York immediately. You’ve caused quite a stir. I’m here. So let me have it—what’s so important? I’m listening.”

I pretend that my eyes are P-38s and my sight is bullets and I blast holes through Linda’s outfit and watch the blood soak through.

She’s so oblivious.

So clueless.

So awful.

“Why are you staring at me like that, Leo?” She’s got her hands on her hips now. “Seriously, you look like the world’s about to end. What do you want from me? I came home. Your teacher says you want to talk. So let’s talk. Were you really pretending to shoot people with that rusty old Nazi gun your father used to carry around in his guitar case? What’s this about? What’s going on? You’re a pacifist, Leo. You wouldn’t hurt a fly. Take one look at the kid and you realize he’s incapable of violence. I told your teacher that, but he seemed really concerned. He says you need therapy. Therapy? I said. Like that ever did anyone any good. Your father and I tried therapy once and look how that ended up. I’ve never met a man or woman who escaped therapy better off than when they started.”

I keep staring.

“Your teacher said you might be suicidal, but I told him that was ridiculous. You’re not suicidal, are you, Leo? Just tell me if you are. We have money. We can get you medicine. Whatever you need. You can have whatever you want. Just ask for it. But I know you’re not suicidal. I know what the real problem is.”

I fucking hate her.

“I told him you do this when you miss your mother, so I came home, Leo. I always come home when you pull one of these pranks. And it wasn’t easy this time either. I had to cancel twelve meetings with important people. Twelve! Not that you would care about that. But someday you are going to have to learn how to live without your mother and—”

“Do you remember when I was little—you used to make me banana pancakes with chocolate chips in them?” I say, because suddenly I have this idea.

Linda just looks at me like my head has spun around 360 degrees.

“You remember, right?” I say.

“What are you talking about, Leo? Pancakes? I wasn’t driven two hours to talk about pancakes.”

“You remember, Mom. We made them together once.”

Linda’s lipstick smiles when she hears me say the word Mom because she hasn’t heard me say that word in many years.

Ironically, she loves to be called Mom.

“Banana–chocolate chip pancakes?” Linda says, and then laughs.

I can tell by the look on her face that she doesn’t remember, but she’s faking like she does. Maybe she only made them once or twice—I dunno. Maybe I made up the memory in my mind. It’s possible. I don’t know why I’m thinking about this memory all of a sudden, but I am.

I remember making banana–chocolate chip pancakes when I was little—like maybe when I was four or five years old—and getting mix everywhere and Dad was softly strumming his acoustic guitar at the kitchen table and my parents were happy that morning, which was rare, and probably why I remember it. Mom and I cooked and then we all ate together as a family.

Normal for most people, but extraordinary for us.

For some reason, I must have banana–chocolate chip pancakes in order for everything to be okay. Right now. It’s the only thing that will help. I don’t know why. That’s just the way it is. I tell myself that if Linda makes me banana–chocolate chip pancakes, I can forgive her for forgetting my birthday. I concoct that deal in my head and then attempt to make her fulfill her end of the unspoken bargain.

“Can you make those for me now—banana–chocolate chip pancakes?” I ask. “That’s all I want from you. Make them, eat breakfast with me, and then you can go back to New York. Okay? Deal?”

“Do we have the ingredients?” she says, looking completely perplexed.

“Shit,” I say, because we don’t. I haven’t been shopping in weeks. “Shit, shit, shit.”

“Do you have to say shit in front of your mother?”

“If I get the ingredients, will you make me breakfast?”

“That’s why you wanted me to come home? Banana–chocolate chip pancakes? That’s why you tricked your teacher into getting so worked up?”

“You make them for me and I won’t give you any more problems all day. You can go back to New York with a clean conscience. Problem solved.”

Linda laughs in a way that lets me know she’s relieved, and then she runs her perfectly manicured nails through my newly stubbled hair, which tickles.

“You really are an odd boy, Leo.”

“Is that a yes?”

“I still don’t understand what happened yesterday. Why did your teacher call me and demand I come home? You seem fine to me.”

Herr Silverman must not have told her it was my birthday, and I don’t even care about that anymore. I just want the fucking pancakes. It’s something Linda is capable of doing. It’s a task she can complete for me. It’s what I can have, so that’s what I want.

“I’ll go get the ingredients, okay?” I say, making it even easier for her.

“Okay,” she says, and then shrugs playfully, like she’s my girlfriend instead of my mom.

I rush past her, down the steps, and out the door without even putting on a coat.

There’s a local grocery about six blocks from our house and I find everything I need there in about ten minutes.

Milk.

Eggs.

Butter.

Pancake mix.

Maple syrup.

Chocolate chips.

Bananas.

On the walk home, with the plastic handles of the grocery bag cutting into my hand, I think about how once again, I’m letting Linda off easy.

I try to concentrate on the pancakes.

I can taste the chocolate and bananas melting in my mouth.

Pancakes are good.

They will fill me.

They are what I can have.

When I arrive home, Linda’s in her office yelling at someone on the phone about the color of tulle. “No, I do not want cadmium fucking orange!” She holds up her index finger when she sees me in the doorway and then waves me away.

In the kitchen I wait five minutes before I decide to do the prep work by myself.

I slice three bananas on the cutting board. Carefully, I make paper-thin cuts. And then I stir milk and eggs into the mix—adding the chocolate chips and banana slices last. I spray the pan and heat it up.

“Linda?” I yell. “Mom?”

She doesn’t answer, so I decide to cook the pancakes, thinking that Linda eating with me can be enough.

I pour some batter onto the pan and it bubbles and sizzles while I pour out three more pancakes. I flip all four and then heat up the oven so I can keep the finished pancakes warm while I cook Mom’s.

“Linda?”

No answer.

“Mom?”

No answer.

I put the finished pancakes into the oven and pour more batter.

I realize I made way too much, but I just keep cooking pancakes, and by the time I finish, I have enough to feed a family of ten.

“Mom?”

I go to her study, and she’s yelling again.

“Jasmine can go fuck herself!” she says, and then sighs.

She’s staring out the window.

She’s oblivious again.

I sigh.

I return to the kitchen.

I eat my banana–chocolate chip pancakes.

They are delicious.

Fuck Linda.

She’s missing out.

She could have had delicious pancakes for breakfast.

I would have forgiven her.

But instead, I use the garbage disposal to grind up all the leftover pancakes.

A few mirror shards fall in.

I let the machine crunch away until it finally jams and I can once again hear Linda cursing at her employees.

She doesn’t come out of her office—not even when I take off and slam the front door behind me so that the whole house shakes.