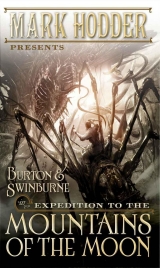

Текст книги "Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Honesty, Spencer, and Sadhvi Raghavendra slipped away.

Burton lay flat on his stomach and levelled his rifle, aiming at the slavers who were moving around their tents and captives.

He flicked a beetle from his cheek and crushed a leech that had attached to the back of his left hand.

Pox hopped from his shoulder to his head and mumbled, “Odious pig.”

The shadows lengthened.

A seemingly endless line of ants marched over the mulch just in front of him. They were carrying leaf fragments, dead wasps, and caterpillars.

He heard Honesty sneeze close by.

A rifle cracked in the near distance.

All of a sudden, gunfire erupted and echoed through the trees, the sound rising up from the base of the hill on the other side of the village. Burton knew what it meant: the Prussians were very close, and Trounce and his team had opened fire on them.

Sheltered behind the roots of trees, the police detective's team could take pot-shots at the hundred and fifty Prussians with impunity. Not only were they concealed but they were also on higher ground, while the pursuing party had to struggle through the marsh before ascending a slope that, while forested, was considerably more open than the uppermost part of the hill.

Trounce, Swinburne, Krishnamurthy, and Isabella Mayson would be silently and invisibly moving backward as they picked off the enemy, drawing the Prussians toward the village and away from the other clearing.

The noise of battle had reached the Arabs. Burton watched as they grabbed rifles and gestured at the forest. A large group of them started running toward where he and the others were hidden.

He took aim at a particularly large and ferocious-looking slaver and shot him through the heart.

Immediately, rifles banged loudly as Honesty, Spencer, and Raghavendra opened fire.

Burton downed two more of the slavers, then, as the other Arabs started shooting blindly into the undergrowth, he crawled backward and repositioned himself behind a tangle of mangrove roots from where he could see the beginning of the path to the village.

Bullets tore through the foliage but none came close to him. He put his rifle aside and pulled two six-shooters from his belt. Four Arabs ran into view. He mowed them down with well-placed shots then crawled away to reposition himself once again.

Slowly, in this fashion, Burton and his friends retreated toward the village.

The slavers followed, and though they sent bullet after bullet crashing into the trees, they didn't once find a target.

On the other side of the empty settlement, Trounce and his companions were performing exactly the same manoeuvre. They had slightly less luck-a bullet had ploughed through Krishnamurthy's forearm and another had scored the skin of Isabella Mayson's right cheek and taken off her earlobe-but the effect was the same: the Prussians were advancing toward the village.

After some minutes, Burton came closer to the end of the path where it opened into the clearing. He fired off three shots and wormed his way under a tamarind tree whose branches slumped all the way to the ground forming an enclosed space around the trunk, and here he found Herbert Spencer collapsed and motionless in the dirt.

A rifle cracked, tamarind leaves parted, and Thomas Honesty crawled in. He saw the bundle of Arabian robes and whispered: “Herbert! Dead?”

“He can't die,” Burton replied in a low voice. “He's clockwork. Fool that I am, I forgot to wind him up this morning-and the key is back with the supplies!”

“Manage without him. Almost there!”

“Let's get into position,” Burton said. “Stay low-things are about to get a lot hotter around here!”

He dropped onto his belly and-followed by the Scotland Yard man-wriggled out from beneath the tamarind, through thorny scrub, and into the shelter of a matted clump of tall grass. Using his elbows, he propelled himself forward until he reached the edge of the village clearing. Honesty crawled to his side. They watched the action from behind a small acacia bush. The police detective glanced at it and murmured, “Needs pruning, hard against the stem.”

Guns were discharging all around them, and they immediately saw that the thing they'd hoped for had come to pass. The slavers had entered the village from the west, while Trounce and his team had lured the Prussians into it from the east; and now the two groups, convinced that the other was the enemy, were blazing away at each other.

“Now we just lie low and wait it out,” Burton said.

Four of the plant vehicles he'd seen at Mzizima were slithering into view, and cries of horror went up from the Arabs, who aimed their matchlocks at the creatures and showered them with bullets. Burton plainly saw the men sitting in the blooms hit over and over, but they appeared unaffected, apart from one who took a shot to the forehead. He went limp, and his plant thrashed wildly before flopping into a quivering heap.

Over the course of the next few minutes, the two forces battled ferociously while the king's agent and his friends looked on from their hiding places in the surrounding vegetation. Then a slight lull in the hostilities occurred and a voice shouted from among the slavers: “We shall not submit to bandits!”

A Prussian, in the Arabic language, yelled back: “We are not bandits!”

“Then why attack us?”

“It was youwho attacked us!”

“You lie!”

“Wait! Hold your fire! I would parley!”

“Damn it!” Burton said under his breath. “We can't let this happen, but if any of us shoots now, they'll realise a third party is present.”

“Is this trickery, son of Allah?” the Prussian shouted.

“Nay!”

“Then tell me, what do you want?”

“We want nothing but to be left alone. We are en route to Zanzibar.”

“Why, then, did you set upon us?”

“I tell you, we did not.”

Burton saw the Prussian turn to some of his men. They talked among themselves, holding their weapons at the ready and not taking their eyes from the Arabs, some of whom were crowded around the end of the westernmost path, while others crouched behind the native huts.

Moments later, the Prussian called: “Prove to us that you are speaking the truth. Lay down your weapons!”

“And allow you to slaughter us?”

“I told you-we are not the aggressor!”

“Then you lay down your guns and withdraw those-those-plant abominations!”

Again, the Prussian consulted with his men.

He turned back to the slavers. “I will only concede to-”

Suddenly, one of the slavers-swathed in his robes and with his head wrapped in a keffiyeh-ran out from among his fellows, raised two pistols, and started blasting at the Prussians.

Immediately, they jerked up their rifles and sent a hail of bullets into the man. He was knocked off his feet, sent twisting through the air, and hit the ground, where he rolled then lay still.

The battle exploded back into life, and, on both sides, man after man went down.

A stray bullet ripped into the tall grass, narrowly missing Burton. He turned to make sure Honesty was unharmed but the Scotland Yard man had, at some point, silently moved away.

“Message to Isabel Arundell,” Burton said to Pox. “Your company is requested. Message ends.”

As the parakeet flew off, one of the plant vehicles writhed past Burton's position and laid into a group of slavers. Its spine-covered tendrils whipped out, yanked men off their feet, and ripped them apart. Some tried to flee but were shot down as the Prussians began to gain control of the clearing. One group of about twenty Arabs had secured itself behind a large stack of firewood in the bandani, and it wasn't long before they were the last remaining men of the slave caravan's force. The Prussians, by contrast, had about fifty soldiers left, plus the three moving plants. Individuals in both groups were drawing swords as ammunition ran out: wicked-looking scimitars on the Arabian side; straight rapiers on the Prussian.

Pox returned: “Message from Isabel Arundell. We had problems getting the buttock-wobbling horses through the bloody swamp but are now regrouping at the bottom of the hill. We'll be with you in a stench-filled moment. Message ends.”

One of the mobile plants crashed into the barrier behind which the slavers were sheltering and lashed out at them, tearing their clothes and flaying their skin. Screaming with terror, they hacked at it with their scimitars, which, in fact, turned out to be a more efficient way to tackle the monster than shooting at it.

An Arab climbed onto the woodpile and jumped from it into the centre of the bloom, bringing his blade swinging down onto the head of the man sitting there. The plant shuddered and lay still.

The cavalry arrived.

The Daughters of Al-Manat, eighty strong and all mounted, came thundering into the village, emerging in single file from the eastern path. With matchlocks cracking, they attacked the remaining Prussians. Spears were thrust into the plant vehicles and burning brands thrown onto them.

Those few slavers who remained alive took the opportunity to flee and plunged away down the path, disappearing into dark shadow, for now the sky was a deep purple and the sun had almost set.

The last Prussian fell with a bullet in his throat.

The Daughters of Al-Manat had been savage-ruthless in their massacre of the enemy who, at Mzizima, had killed thirty or so of their number. Now they reined in their horses and waited while Sir Richard Francis Burton and the others emerged from the vegetation.

Krishnamurthy was holding his forearm tightly and blood was dribbling between his fingers. Isabella Mayson's right ear had bled profusely and her clothes were stained red. Swinburne, Trounce, and Sister Raghavendra were uninjured. They were all wet through and covered with dirt and insects.

“Well done,” Burton told them.

“Where's Tom?” Trounce asked.

“Probably dragging Herbert out of the bushes-his spring wound down. Sadhvi, would you see to Isabella and Maneesh's wounds?”

While the nurse got to work, Burton indicated to Trounce the area where Spencer had been left, then paced over to Isabel Arundell, who was sitting on her horse quietly conversing with her Amazons.

“That was brutal,” he observed.

She looked down at him. “I lost a lot of good women at Mzizima and on the way here. Revenge seemed…appropriate.”

He regarded her, moistened his lips, and said, “You're not the Isabel I met twelve years ago.”

“Time changes people, Dick.”

“Hardens them?”

“Perhaps that is necessary in some cases. Are we to philosophise while slaves remain in shackles or shall we go and liberate them?”

“Wait here a moment.”

He left her and approached Swinburne.

“Algy, I want you and Maneesh to leg it along to the other clearing. Bring the villagers, Said, and our porters back here. They can help move the bodies out to the fields. They'll need to start work digging a pit for a mass grave.”

He returned to Isabel. She indicated a riderless horse, which he mounted. Holding burning brands to light the way, they led a party of ten of the Daughters out of the glade and along the path to the fields. Burton felt sickened by the slaughter he'd witnessed but he knew it was the only option. On the one hand, the Prussians would certainly have killed him and his party, but on the other, he couldn't allow the villagers to fall into the hands of Tippu Tip.

They rode out of the forest and approached the caravan. Five Arabs were guarding it.

“He who raises a weapon shall be shot instantly!” Burton called.

One of the guards bent and placed his matchlock on the ground. The others saw him do it and followed suit.

Burton and Isabel stopped, dismounted, and walked over to them.

“Where is el Murgebi, the man they call Tippu Tip?” Burton asked, in Arabic.

One of the men pointed to a nearby tent. Burton turned to Isabel's Amazons and said, “Take these men and make a chain gang of them. Then get to work liberating the slaves.”

The women looked for confirmation from Isabel. She gave them a nod, then she and Burton strode over to the tent, pushed aside its flap, and stepped in.

By the light of three oil lamps, they saw colourful rugs on the ground, a low table holding platters of food, and piles of cushions upon which sat a small half-African, half-Arabian individual. His teeth were gold, and though he appeared less than thirty years old, his beard was white. He raised his turbaned head and they noted that a milky film covered his eyes. He was blind.

“Who enters?” he asked in a reedy voice.

“Thy enemy,” Burton replied.

“Ah. Wilt thou take a sweet mint tea with me? I have been listening to the noise of battle. An exhausting business, is it not? Refreshment would be welcome, I expect.”

“No, Tippu Tip, I will not drink with thee. Stand up, please.”

“Am I to be executed?”

“No. There has been enough death this night.”

“Then what?”

“Come.”

Burton stepped forward, took the trader by the elbow, and marched him out of the tent and over to the chained-up slaves. Isabel followed and said nothing. Her women were busily releasing the four hundred captives, who, in a long line, were making their way toward the village.

As Burton had ordered, the five guards were now tethered together, with short chains running from iron collar to iron collar, and from ankle manacle to ankle manacle. Their hands were tied behind their backs. The king's agent positioned Tippu Tip at the front of the line and locked him in fetters, joining him to the chain gang but leaving his hands unbound. He then pulled the prisoners along, away from the crowd of slaves and out into the open field.

“What are you doing?” Isabel whispered.

“Administering justice,” he replied, and brought them to a halt. “Aim your matchlock at Tippu Tip, please, Isabel.”

“Am I to be a firing squad of one?”

“Only if he attempts to point this at us,” the king's agent responded, holding up a revolver. He placed it in the Arabian's hand and stepped away. The slaver's face bore an expression of bafflement.

“Listen carefully,” Burton said, addressing the prisoners. “You are facing east, toward Zanzibar. However, if you walk straight ahead, you will find yourselves among the villagers and slaves we have just liberated and they will surely tear you limb from limb. You should therefore turn to your left and walk some miles north before then turning again eastward. In the morning, the sun will guide you, but now it is night, a dangerous time to travel, for the lions hunt and the terrain is treacherous in the dark. I can do nothing to make the ground even, but I can at least give you some protection against predators. Thus, your leader holds a pistol loaded with six bullets. Unfortunately, he is blind, so you must advise him where to point it and when to pull the trigger to ward off anything that might threaten you, but be cautious, for those six bullets are the only ones you have. Perhaps if walking all the way to Zanzibar is too challenging a prospect for you-well, there are six bullets and there are six of you. Need I say more?”

“Surely thou cannot expect us to walk all the way to the coast in chains?” Tippu Tip protested.

“Didst thou not expect just that of thy captives?” Burton asked.

“But they are slaves!”

“They are men and women and children. Now, begin your journey, you have far to go.”

“Allah have mercy!” one of the men cried.

“Perhaps he will,” Burton said. “But I won't.”

The man at the back of the line wailed, “What shall we do, el Murgebi?”

“Walk, fool!” the slave trader barked.

The chain gang stumbled into motion and slowly moved away.

“Tippu Tip!” Burton called after it. “Beware of Abdullah the Dervish, for if I set mine eyes on thee again, I shall surely kill thee!”

No one slept that night.

The liberated slaves carried the dead Arabs and Prussians along the path and into the fields, leaving them in a distant corner, intending to dig a mass grave when daylight returned. A number of Isabel's women stood guard over the corpses to prevent scavengers getting to them. The Africans were too afraid to do the job, believing that vengeful spirits would rise up and attack them.

Of the four hundred slaves, most had been taken from villages much farther to the west. This turned out to be a blessing, for Burton's porters had been so terrified by the sounds of battle and proximity of slavers that they'd overpowered Said and his men and had melted away into the night. No doubt they were fleeing back the way the expedition had come. Fortunately, their fear had outweighed their avariciousness and they'd departed without stealing supplies. The released slaves agreed to replace the porters on the understanding that each man, as he neared his native village, would abandon the safari in order to return home. Burton calculated that this would at least cover the marches from Dut'humi to distant Ugogi.

The Arab camp was stripped of its supplies, which were added to Burton's own and stored in the village's bandani.Tippu Tip's mules were also appropriated.

A large fire was built and the plant vehicles were chopped up and thrown into the flames.

The Daughters of Al-Manat corralled their hundred and eight horses.

“We're starting to lose them to tsetse bites,” Isabel informed Burton. “Twelve, so far. These animals were bred in dry desert air. This climate is not good for them-it drains their resistance. Soon we'll be fighting on foot.”

“Fighting whom?”

“The Prussians won't give up, Dick. And remember, John Speke almost certainly has a detachment of them travelling with him.”

“Hmm. Led by Count Zeppelin, no doubt,” Burton muttered.

“He may be taking a different trail from us,” Isabel observed, “but at some point we're bound to clash.”

Swinburne bounded over, still overexcited, and moving as if he'd come down with a chronic case of St. Vitus's dance.

“My hat, Richard! I can't stop marvelling at it! We were outnumbered on both sides yet came out of it without a scratch, unless you count the five thousand three hundred and twenty-six that were inflicted by thorns and hungry insects!”

“You've counted them?” Isabel asked.

“My dear Al-Manat, it's a well-educated guess. I say, Richard, where the devil has Tom Honesty got to?”

Burton frowned. “He's not been seen?”

“Not by me, at least.”

“Algy, unpack some oil lamps, gather a few villagers, and search the vegetation over there-” He pointed to where he'd last seen the Scotland Yard man. “I hope I'm wrong, but he may have been hit.”

Swinburne raced off to organise the search party. Burton left Isabel and joined Trounce at the bandani.The detective was rummaging in a crate and pulling from it items of food, such as beef jerky and corn biscuits.

“I'm trying to find something decent for us to chow on,” he said. “I don't think the villagers will manage to feed everybody. I put Herbert over there. He still needs winding.”

Burton looked to where Trounce indicated and saw the clockwork man lying stiffly in the shadow of the woodpile. The king's agent suddenly reached out and gripped his friend's arm. “William! Who found him?”

“I did. He was in a hollow under a tree.”

“Like that?”

“Yes. What do you mean?”

“Look at him, man! He had Arabian robes covering his polymethylene suit. Where are they?”

“Perhaps they hindered his movement, so he took them off. Why is it important?”

Burton's jaw worked. For a moment, he found it impossible to speak. His legs felt as if they couldn't hold him, and he collapsed down onto a roll of cloth, sitting with one arm outstretched, still clutching Trounce.

“Bismillah! The bloody fool!” he whispered and looked up at his friend.

Trounce was shocked to see that the explorer's normally sullen eyes were filled with pain.

“What's happened?” he asked.

“Tom was next to me when the Prussians and Arabs started to powwow,” Burton explained huskily. “We were near Herbert, just a little way past him. The parley threatened to ruin our entire plan. The Arab who lost patience with the conflab and ran out shooting saved the day for us. Except-”

“Oh no!” Trounce gasped as the truth dawned.

“I think Tom may have crawled back to Herbert, taken his robes, put them on, and-”

“No!” Trounce repeated.

They gazed at each other, frozen in a moment of anguish, then Burton stood and said, “I'm going to check the bodies.”

“I'm coming with you.”

They borrowed a couple of horses from Isabel and, by the light of brands, guided their mounts along the path to the fields then galloped across the cultivated ground to where the dead had been laid out. Dismounting, they walked up and down the rows, examining the corpses. The Prussians were ignored, but each time either man came to a slaver, he bent and pulled back the cloth that covered the corpse's face.

“William,” Burton said quietly.

Trounce looked up from the man he'd just inspected and saw the explorer standing over a body. Burton's shoulders were hunched and his arms hung loosely.

Something like a sob escaped from the Scotland Yard man, and the world seemed to whirl dizzyingly around him as he staggered over to his friend's side and looked down at Thomas Manfred Honesty.

His fellow detective was wrapped in the robes-ragged and blood-stained-that he'd borrowed from Spencer. He'd been riddled with bullets and must have died instantly, but it was no consolation to Trounce, for the little man, who'd mocked him for nearly two decades over his belief in Spring Heeled Jack, had, in the past couple of years, become one of his best friends.

“He sacrificed himself to save us,” Burton whispered.

Trounce couldn't reply.

They buried Thomas Honesty the next morning, in the little glade to the north of the village.

Burton spoke of his friend's bravery, determination, and heroism.

Trounce talked hoarsely of Honesty's many years of police service, his exemplary record, his wife, and his fondness for gardening.

Krishnamurthy told of the respect the detective inspector had earned from the lower ranks in the force.

Swinburne stepped forward, placed a wreath of jungle flowers on the grave, and said:

“For thee, O now a silent soul, my brother,

Take at my hands this garland, and farewell.”

Sister Raghavendra softly sang “Abide with Me,” then they filed back along the trail to the village, a subdued and saddened group.

For most of the rest of the day, Burton and his fellows caught up with lost sleep. Not so William Trounce. He'd found a large flat stone on the slope beneath the village, and, borrowing a chisel-like tool from one of the locals, he set about carving an inscription into it, sitting alone, far enough away from the huts that his chipping and scraping wouldn't disturb his slumbering companions. It took him the better part of the day to complete it, and when it was done, he took it to the glade, placed it on the grave, and sat on the grass.

“I'm not sure I really understand it, old chap,” he murmured, “but apparently the whole Spring Heeled Jack business sent us all off in a different direction. None of us is doing what we were supposed to be doing, although I rather think I would have carried on as policemen no matter what.”

He rested a hand on the stone.

“Captain Burton says this history we're in isn't the only one, and, in any of the others, meddlers like Edward Oxford might be at work, and whenever they tamper with events, they cause new histories. Can you imagine that? All those different variations of you and me? The thing of it is, my friend, I hope-I really hope-that, somewhere, a Tom Honesty will be tending his garden well into old age.”

He sat for a few minutes more, then bent over and kissed the stone, stood, sighed, and walked away.

The tear he left behind trickled into the inscription, ran down the tail of the letter “y,” and settled around a seed in Swinburne's wreath.