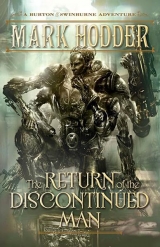

Текст книги "The Return of the Discontinued Man"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанры:

Киберпанк

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“You took quite a gamble.”

“He was holding my head right next to his own. I had no other cards to play.” He examined the room. “I appear to have been oblivious for some time. How long?”

“About twelve hours,” she replied. “There was some sort of backlash from his—from your—babbage device. The chronostatic energy ignited the room. Everything in it—apart from you, of course—burned ferociously. The time suits are destroyed.”

“Resonance, I suppose. It started all this, now it has ended it.”

With visible reluctance, Raghavendra pointed to the floor on Burton’s right. He looked and saw what appeared to be a large and twisted stick of charcoal. Horrified, he recognised it as his own corpse.

“Your and Herbert’s bodies were cremated,” Raghavendra said. “There’s little chance of cloning, apparently.”

Burton acknowledged the revelation with a grunt that came out as a clink. He extended a metal foot and dragged a line through the ash. “The diamond fragments from the Nimtz generators and helmets must be among the ashes. We’ll have to collect them. Where are Trounce and Bendyshe?”

“William went some hours ago to find Mr. Grub, the vendor. Unless someone gives the Lowlies focus, riots are inevitable. We’re hoping Grub will spread the news that the prime minister and his cronies have been overthrown. Mr. Bendyshe, meanwhile, has taken Jessica Cornish to the Orpheus. Captain Lawless flew it here and landed in Green Park. We’ve all been waiting to assess your status.”

“My status?”

“We could see the Brunel body was still functioning by the glow of its eyes, but we didn’t know whether it was you or Oxford inside it.”

“Ah, I see. And Bendyshe is all right?”

“Lorena Brabrooke did something to the nanomechs in him. ‘Deactivated’ is the word, I believe. As for the rest of it, all the equerries and constables have stopped functioning and the palace’s inhabitants are wandering around like lost children.”

“Would you see if any of them knows where Brunel’s battery pack is, Sadhvi? It must be somewhere in the palace, and I feel I might require it soon.”

She nodded, glanced at Swinburne, and looked back at Burton. “I’ll organise a search party, if necessary. There’s a well-appointed lounge one hundred floors down, which we’ve chosen as our base of operations. I suggest you settle in there to recover from your ordeal.”

She smiled at him and left the chamber.

Burton clanked over to Swinburne. He felt disoriented and clumsy.

Isabel betrayed me.

He dismissed the thought. Time for that later.

I have all the time in the world.

With a hiss and ratcheting of gears, he squatted beside his friend, reached out, and prodded the poet’s arm. “Hallo there.”

Swinburne raised his wet face from his hands and smiled weakly. “What ho.”

“Quite a rum do, hey?”

“I suppose so. You sound awful. Ding dong, ding dong. I hardly know if it’s you or Brunel or Oxford. We shall have to make it Gooch’s top priority to fashion for you a more human-sounding vocal apparatus.”

“Thank you, Algy.”

“Don’t thank me, thank Daniel, he’s the one who’ll create it.”

“I mean for what you did.”

Swinburne suddenly giggled. “My pleasure, Richard. Any time you need shooting dead, don’t hesitate to ask.”

Burton whirred upright and held out a hand. Swinburne grasped it and got to his feet. He looked over to his friend’s still-smouldering corpse and emitted a groan. “By God, Oxford aged you thirty years in a matter of minutes. I saw you become an old man.”

“And I witnessed my life as it would have been had Oxford never altered history.”

“And?”

“Let us just say, it had a theme.”

Swinburne gave an inquisitive twitch of his eyebrows.

Burton ignored it and turned toward the doors. “I want to get out of this chamber, never to see it again. Lead me to the lounge, will you?”

They left the domed room, walked to the nearest lift, and entered it, a massive man of brass and cogs and pistons, and a diminutive red-haired poet.

“What a strange insanity,” Swinburne mused as they started down, “to create a future from a jumbled, misunderstood vision of the past.”

“Isn’t that what we all do?” Burton asked.

His companion had no answer to that, and for the rest of the descent they stood in thoughtful silence.

The lift stopped, and they passed from it into a vestibule, and from there the poet led his friend to the grand lounge, which was filled with couches, armchairs, bookcases, tables, cabinets, and statuettes of the erstwhile queen. The walls were hung with portraits, every one of them depicting Jessica Cornish.

Gladys Tweedy, the Marquess of Hammersmith, Minister of Language Revivification and Purification, was the room’s sole occupant. She stood as they entered.

“Prime Minister?” she asked doubtfully.

“Dead,” the king’s agent chimed. “I’m Burton.”

“Really? How thoroughly singular. You’re joking, of course.”

“No.”

Swinburne scampered over to a drinks cabinet and eagerly examined its contents.

“But you look and sound just like the prime minister,” Tweedy protested.

“I know. I’m not particularly thrilled about it. Marquess, what is the situation with regards to the mobilisation of our troops?”

“Our forces are awaiting orders from the Minister of War, Death and Destruction, who, might I remind you, recently experienced a violent demise. You will have to appoint a successor.”

“I’ll do no such thing. The war is cancelled.”

“Hurrah!” Swinburne cheered. “Hooray and yahoo!” He held up a bottle. “Vintage brandy!”

Burton said to the marquess, “Will you convey a message to your fellow ministers?”

“If you wish,” she answered. “Or to those that survived, anyway. Quite a few didn’t get out in time.”

“Tell them that Parliament is suspended and all ministers are relieved of their duties. The people will fashion a new form of government in due course.”

She widened her eyes and put a hand to her mouth. “What people?”

“You call them Lowlies.”

She laughed. “But they’re little more than animals!”

“Do as I say.”

Gladys Tweedy swallowed, stuck out her bottom lip, put her hands on her hips, and stamped out of the room, pushing past William Trounce as he entered.

“By Jove! She looks annoyed! Have you—” He saw Burton and quickly drew his pistol.

“Steady, Pouncer!” Swinburne shrilled. “It’s Richard.”

“Richard?” Uncertainly, Trounce lowered his gun. “You mean—it—he’s in—it worked? By Jove!”

“Why don’t you stop ‘by Joving’ and have a tipple?” the poet suggested. He poured three drinks, met his companions in the middle of the room, handed a glass to Trounce, and held another out to Burton. He blinked and said, “Oops! Oh crikey. You poor thing.”

A wave of grief hit the king’s agent.

I can’t taste. There’s no physical sensation. I’m dead.

He pushed the emotion aside: something else to be dealt with later.

“Oh well,” Swinburne muttered. He looked down at the drinks. “One for each hand.”

Burton noticed, at the other end of the chamber, French doors, and beyond them, a balcony. He strode over, followed by Swinburne and Trounce, and pulled them open. Their handles snapped off in his hands.

“Damn!” he exclaimed. “I have to familiarise myself with this body. It’s fiendishly strong.”

“By my Aunt Penelope’s plentiful petticoats!” Swinburne cried out. “Close the doors. It’s freezing.”

“In a moment,” Burton said. He stepped out onto the balcony, into twelve-inch-deep scarlet snow.

Swinburne gulped one of his brandies, ran to the side of the room, and tore a couple of tapestries down from the wall. He wrapped one around himself and handed the other to Trounce, who did likewise. They joined Burton. The air at this altitude was thin but breathable.

They looked out over London.

Under a clear afternoon sky, the city sprawled, blanketed in red.

“I was born here,” Trounce said. “But it doesn’t feel like home. I miss the hustle and bustle of the nineteenth century. I even miss the smells.”

“It’s all down there,” Burton noted. “Under the ground, waiting to be liberated.”

“Humph! It is, but that hustle and bustle isn’t my hustle and bustle.”

“I miss Verbena Lodge,” Swinburne said. “Twenty-third-century bordellos are absolutely hopeless. They have no understanding of the lash.”

Burton asked, “Will you both come back to 1860?”

The question was met by a prolonged silence.

The poet broke it. “I don’t know whether I can. I feel I have an obligation to fulfill.”

“Likewise,” Trounce said. “There’s much work to be done here, Richard. I fear I may never be reunited with my bowler or with Scotland Yard.” He paused. “You’ll go?”

“I have to. My brother will expect from me a full account of what has occurred here.”

“And after that, what? Will you masquerade as Brunel?”

“I hardly know one end of a spanner from another.” Burton leaned on the balcony’s parapet then suddenly remembered his great weight and stepped back, afraid that it might give way beneath him. “I require time to adapt to this body before I return. Once I’m there—well, I’ll see what happens.”

Swinburne bent and scooped up a handful of snow. He examined it. “The seeds are sending out roots. The jungle is obviously up to something. I wonder what?”

Burton’s neck buzzed as he turned his head to look down at his friend. “It’s you.”

“But I never know what I’m going to do next, even in human form.”

Burton snorted. It sounded like the clash of a cymbal. “I can’t imagine how it feels to know you’re a vegetable.”

“Probably not much different to the awareness that you’re an accumulation of cogwheels and springs. My hat, Richard! Animal, vegetable and mineral. What are we all becoming?”

Burton looked toward the tower-forested horizon.

“Time will tell, Algy. Time will tell.”

ISABEL ARUNDELL (1831–1896)

Isabel and Richard Francis Burton met in 1851 and, after a ten-year courtship, married in 1861. Marriage brought a change of fortune for Burton, seeing him more or less abandon exploration in favour of writing and the translating of forbidden literature of anthropological interest. Notoriously, upon his death in 1890, Isabel burned her husband’s papers, journals and unfinished work. She also consigned to the flames his translation of The Scented Garden, which he considered his magnum opus, and which he’d finished just the day before his demise.

ERNEST AUGUSTUS I (1771–1851)

Ernest Augustus I was the son of George III. When his niece, Victoria, became queen of the United Kingdom in 1837, Ernest was made king of Hanover, which ended the union between Britain and Hanover that had begun in 1714. Had Victoria been assassinated, Ernest would have been a prime candidate to replace her as the United Kingdom’s monarch. With rumours of murder and incest attached to Ernest’s name, this would not have been a popular choice.

CHARLES BABBAGE (1791–1871)

Mathematician, inventor, philosopher and engineer, Charles Babbage is considered the father of modern computers. He created steam-powered devices that were the first to demonstrate that calculations could be mechanised. However, his most complex creations, the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine, were not completed in his lifetime due to funding and personality problems. By 1860, he was becoming increasingly eccentric, obsessive and irascible, directing his ire in particular at street musicians, commoners, and children’s hoops.

BATTERSEA POWER STATION

The station was neither designed nor built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and did not exist during the Victorian Age. Actually comprised of two stations, it was first proposed in 1927 by the London Power Company. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (who created the iconic red telephone box) designed the building’s exterior. The first station was constructed between 1929 and 1933. The second station, a mirror image of the first, was built between 1953 and 1955. Considered a London landmark, both stations are still standing but are derelict.

JAMES BRUCE, EIGHTH EARL OF ELGIN (1811–1863)

Lord Elgin, orator, humanist, and administrator, was the British governor-general of Canada and later served diplomatic posts in China, Japan, and India. He did not say, “Talk, talk, talk, and while you are talking, the Chinese are exacting yet another tax, . . .”

ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL (1806–1859)

The British Empire’s most celebrated civil and mechanical engineer, Brunel designed and built dockyards, railway systems, steamships, bridges and tunnels. A very heavy smoker, in 1859 he suffered a stroke and died, at just fifty-nine years old.

EDWARD JOSEPH BURTON (1824–1895)

Richard Francis Burton’s younger brother shared his wild youth but later settled into army life. Extremely handsome and a talented violinist, he became an enthusiastic hunter, which proved his undoing—in 1856, his killing of elephants so enraged Singhalese villagers that they beat him senseless. The following year, still not properly recovered, he fought valiantly during the Indian Mutiny but was so severely affected by sunstroke that he suffered a psychotic reaction. He never spoke again. For much of the remaining thirty-seven years of his life, he was a patient in the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum.

THE CANNIBAL CLUB

In 1863, Burton and Dr. James Hunt established the Anthropological Society, through which to publish books concerning ethnological and anthropological matters. As an offshoot of the society, the Cannibal Club was a dining (and drinking) club for Burton and Hunt’s closest cohorts: Richard Monckton Milnes, Algernon Swinburne, Henry Murray, Sir Edward Brabrooke, Thomas Bendyshe, and Charles Bradlaugh.

CAPTAIN SIR RICHARD FRANCIS BURTON (1821–1890)

1860 was one of the darkest periods of Burton’s life. Having returned the previous year from his expedition to locate the source of the Nile, he was engaged in a war of words with Lieutenant John Hanning Speke, who’d accompanied him during the gruelling trek through Africa. Though the expedition was Burton’s from the outset, and Speke was the junior officer, the lieutenant returned to London ahead of Burton and laid claim to having discovered the source independent of him. Feeling sidelined and badly betrayed by a man he’d considered a friend, Burton hoped to find some happiness through marriage to Isabel Arundell. Unfortunately, her parents forbade it. With everything going wrong, Burton escaped to America and embarked on an ill-recorded and extremely drunken tour.

MICK FARREN (1943–2013)

A singer-songwriter, music journalist and science fiction author, Farren fronted the proto-punk band the Deviants. During the late sixties, he was for a brief period at the helm of the underground newspaper International Times and also ran a magazine called Nasty Tales, which he successfully defended from an obscenity charge. His essay for the New Musical Express, entitled “The Titanic Sails at Dawn,” is considered a seminal analysis of the state of the music industry during the mid-seventies and a clarion call for the birth of punk rock. Farren continued to write novels, poetry and songs, and to perform with the Deviants, right up until his death onstage at the Borderline Club in London on July 27, 2013.

GEORGE V (GEORGE FREDERICK ALEXANDER CHARLES ERNEST AUGUSTUS) (1819–1878)

George V, the son of Ernest Augustus I, was the last king of Hanover. His reign ended with the unification of Germany.

SIR DANIEL GOOCH (1816–1889)

Daniel Gooch was a railway engineer who worked with such luminaries as Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He was the first chief mechanical engineer of the Great Western Railway and was later its chairman. Gooch was also involved in the laying of the first successful transatlantic telegraph cable and became the chairman of the Telegraph Construction Company. Later in life he was elected to office as a parliamentary minister. He was knighted in 1866.

THE GROSVENOR SQUARE RIOT OF 1968

On March 17, Grosvenor Square, London, was the scene of an anti–Vietnam War demonstration that quickly turned into a riot due to what many regarded as heavy-handed police tactics. It ended with eighty-six people injured and two hundred demonstrators arrested. Mick Farren was present.

RICHARD MONCKTON MILNES, 1ST BARON HOUGHTON (1809–1885)

Monckton Milnes was a poet, socialite, politician, patron of the arts, and collector of erotic and esoteric literature. He was also one of Sir Richard Francis Burton’s closest friends and supporters.

JOHN HANNING SPEKE (1827–1864)

An officer in the British Indian Army, Speke accompanied Burton first on his ill-fated expedition to Somalia, which ended when their camp was attacked at Berbera. Speke was captured and pierced through the arms, side and thighs by a spear before somehow managing to escape and run away. This expedition also marked the beginning of his deep resentment of Burton, caused by his misunderstanding of a command, which he took to be a derisory comment concerning his courage. When Speke accompanied Burton on his search for the source of the Nile from 1857 to 1859, their relationship quickly broke down. Speke then returned to London ahead of his commanding officer and sought to claim sole credit for the discovery. The two men fought a bitter war of words until 1864, when Speke shot himself while out hunting.

HERBERT SPENCER (1820–1903)

One of the most influential, accomplished, and misunderstood philosophers in British history, Herbert Spencer melded Darwinism with sociology. He originated the phrase “survival of the fittest,” which was then taken up by Darwin himself. It was also adopted, misinterpreted, and misused by a number of governments, who employed it to justify their eugenics programs, culminating in the Holocaust of the 1940s. Spencer, unfortunately, thus became associated with one of the darkest periods in modern history. Bizarrely, he is also credited with the invention of the paper clip.

SPRING HEELED JACK

Spring Heeled Jack is one of the great mysteries of the Victorian age (and beyond). This ghost or apparition, creature or trickster, was able to leap to an extraordinary height. Helmeted and cloaked, it breathed blue fire and frightened unsuspecting victims, mostly young women, over a period mainly from 1837 to 1888 but also extending into the twenty-first century.

ABRAHAM "BRAM" STOKER (1847–1912)

Born in Dublin, Ireland, thirteen-year-old Stoker was still at school in 1860. In adulthood, he became the personal assistant of actor Henry Irving and business manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London. On August 13, 1878, Stoker met Sir Richard Francis Burton for the first time and described him as follows: “The man riveted my attention. He was dark and forceful, and masterful, and ruthless. I have never seen so iron a countenance. As he spoke the upper lip rose and his canine tooth showed its full length like the gleam of a dagger.” Stoker’s novel Dracula was published in 1897.

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE (1837–1909)

A celebrated poet, playwright, novelist and critic, Swinburne was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in every year from 1903 to 1907 and once more in 1909. In 1860, Swinburne returned to Balliol College, Oxford, having been rusticated the year before. He never received a degree and after leaving the college plunged into literary circles where he quickly gained a reputation as a great poet, an extreme eccentric, and a very heavy drinker. Swinburne is thought to have suffered a condition through which he sensed pain as pleasure, which might explain his masochistic tendencies. He and Burton were very close friends.

“And grief shall endure not for ever, I know . . .”

–From The Triumph of Time

“I hid my heart in a nest of roses . . .”

–From A Ballad of Dreamland, Poems & Ballads (second and third series)

TERMINAL EMANATION

Though it’s been theorised for many years, research was published during the writing of this novel that supports the proposition that the brain sends out a strong electromagnetic pulse at the moment of death. According to the Washington Post: “Scientists from the University of Michigan recorded electroencephalogram (EEG) signals in nine anesthetized rats after inducing cardiac arrest. Within the first 30 seconds after the heart had stopped, all the mammals displayed a surge of highly synchronized brain activity that had features associated with consciousness and visual activation. The burst of electrical patterns even exceeded levels seen during a normal, awake state.” (Source: “Surge of Brain Activity May Explain Near-Death Experience, Study Says,” Washingtonpost.com, August 12, 2013.)

HERBERT GEORGE WELLS (1866–1946)

A prolific writer, Wells is best remembered for his science fiction. He was also a proponent of the idea that the world would function best under the auspices of a single state.

“The only true measure of success is the ratio between what we might have done and what we might have been on the one hand, and the thing we have made and the things we have made of ourselves on the other.”

“Adapt or perish, now as ever, is nature’s inexorable imperative.”

“The Anglo-Saxon genius for parliamentary government asserted itself; there was a great deal of talk and no decisive action.”

—From The Invisible Man

“Socialism is the preparation for that higher Anarchism; painfully, laboriously we mean to destroy false ideas of property and self, eliminate unjust laws and poisonous and hateful suggestions and prejudices, create a system of social right-dealing and a tradition of right-feeling and action. Socialism is the schoolroom of true and noble Anarchism, wherein by training and restraint we shall make free men.”

—From New Worlds for Old

Throughout the Burton & Swinburne series, I’ve used real people from history as the basis for many of my characters. Mostly Victorians, they are long dead and thus cannot be properly known, no matter how many biographies of them might be read. However, the truth of their many achievements can be explored, and to compensate for the liberties I’ve taken with their personalities, I’ve added to each novel an addendum to highlight aspects of their real lives, hoping that my readers are curious enough to research a little further.

With Mick Farren it’s been different. With Mick, when I started this novel, I was introducing into the series a man who still lived.

For those of you unfamiliar with him, Mick was an important voice in the UK counterculture who rose to prominence during the late 1960s. He was the editor of the alternative newspaper International Times, a songwriter and lead singer in the rock group the Deviants, a music journalist (he accurately predicted and supported the advent of punk), and a science fiction novelist.

You can probably understand that I felt rather apprehensive when I approached him and asked if I could hijack him for a work of fiction. I sent him the first three Burton & Swinburne novels to read. I told him what I intended. I made it clear that the Mick I wanted to portray would be, at best, an approximation of the real thing.

He was delighted. Really. He laughed, he enthused, and he said he was thoroughly flattered. “Damn! I love it. I’d be delighted. Do your worst. Burton has always been a major hero of mine.”

So I went ahead, got writing, and sent the early draft chapters to him. He gave me a thumbs-up. We communicated regularly over a period of about six months.

Then he died.

This man, who was one of my heroes, who was fast becoming my friend, got up on stage with the Deviants on Saturday, July 27, 2013, and, after two songs, suffered a heart attack, collapsed, and didn’t regain consciousness.

He never got to read this novel.

I never got to say thank you or good-bye.

So I’ll say it now. Thank you, Mick. You inspired me, impressed me, entertained me and intrigued me. Thank you for the Deviants. Thank you for the novels and many brilliant articles. Thank you for so enthusiastically embracing what I have done with you in The Return of the Discontinued Man.

And good-bye. I’ll miss you. I hope everybody who reads this novel looks you up on Wikipedia, listens to your music, and buys your books. I’m glad you went out rockin’.

Mark Hodder

Valencia, Spain

Photo by Yolanda Lerma Palomares

Mark Hodder was born in Southampton, England, but has lived in Winchester, Maidstone, Norwich, Herne Bay, and for many years in London. He has worked as a roadie; a pizza cook; a litter collector; a glass packer; an illustrator; a radio commercial scriptwriter; an advertising copywriter; and a BBC web producer, journalist, and editor. In 2008, he moved to Valencia, Spain, where he settled with his Spanish partner, Yolanda. Initially, he earned a living by teaching English, but then he wrote his first novel, The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack, which promptly won the Philip K. Dick Award 2010. Mark immediately and enthusiastically became a full-time novelist, thus fulfilling his wildest dreams, which he started having around the age of eleven after reading Michael Moorcock, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, Philip K. Dick, P. G. Wodehouse, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He recently became the father of twins, Luca Max and Iris Angell.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Also by Mark Hodder

Dedication

Contents

THE FIRST PART: THE VISIONS

1 AN APPARITION IN LEICESTER SQUARE

2 AN EXPERIMENT GONE AWRY

3 AN EVENING WITH ORPHEUS

4 RECURRENCES

5 THE JUNGLE

6 THE SECOND EXPERIMENT

7 ECHOES OF OXFORD

8 THE DREAMING ROSE

9 AN UNLIKELY EXPEDITION

THE SECOND PART: THE VOYAGE

10 THE APATHY OF 1914

11 THE SQUARES, CATS AND DEVIANTS OF 1968

12 THE GROSVENOR SQUARE RIOT OF 1968

13 AN OLD FRIEND IN 2022

14 THE ILLUSORY WORLD OF 2130

15 THE TRUTH OF 2130 REVEALED

THE THIRD PART: THE FUTURE

16 ARRIVAL: 2202

17 THE UPPERS AND THE LOWLIES

18 HER MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA

19 A PLEA TO PARLIAMENT

20 SEVEN BIRTHS AND A DEATH

21 BODIES

APPENDIX: MEANWHILE, IN THE VICTORIAN AGE AND BEYOND . . .

AFTERWORD

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Back Cover