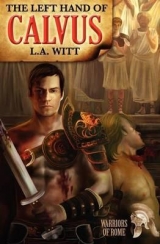

Текст книги "The Left Hand of Calvus"

Автор книги: L. A. Witt

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

The Left Hand of Calvus

by L.A. Witt

In accordance with the prophecy, this book is dedicated to Aleks, Rachel, and Sarah for never letting “good enough” be good enough.

So this is Pompeii. The prosperous city at the base of Vesuvius.

I’ve heard the tales about this place. Quiet. Warm. Near the sea. Until recently, with the rudis of freedom so close I could almost feel its wooden hilt in my hands, I had considered coming here to make my home once I was no longer a slave. That is until Fortune decided I should remain in bondage. I’d had perhaps three fights left, but now I, along with two other men from my familia gladiatori, are on our way to the Pompeiian politician who’s now our master.

In spite of the fact that I’d lost my chance at freedom, the rest of the men in the familia had been envious.

“A nobleman?In Pompeii?” One had slapped my arm. “You lucky bastard!”

“Agreed,” another had said. “You won’t be in the arena anymore, and if you’ve got to stay a slave, Saevius, you could do worse than to live out your days as some rich bastard’s bodyguard.”

A third had added, “Pompeii? I hear in that place, the wine they pour in noblemen’s houses tastes like the lips of Venus herself.”

The other men traveling with me had been thrilled by that notion. Me, I’m as enthusiastic about any woman’s lips, including Venus’s, as I am about spending the rest of my days a fucking slave, so I’d simply muttered, “I’ll be sure to give my regards to Bacchus.”

What servant drinks the same wine as his masters, I can hardly imagine. But never mind, because the wine here is probably no different from what flows in Rome. After all, Pompeii doesn’t seem much different from Rome, if you ask me. A great deal smaller, yes, and much less crowded. At least in this part of the city, though, it’s all the same terracotta roofs and limestone walls and, as we near the market, people dragging unruly livestock down stone streets past lumbering carts and clouds of buzzing flies. Smells like bread, sweat, fish, and dung, just like Rome, with chickens talking over the shouting bakers, fishmongers, butchers, and vintners while hammering and banging come from workshops behind shop fronts and booths. Perhaps I should have considered retiring to Herculaneum instead. Then again, if Pompeii isn’t in life what it is in stories, then Herculaneum likely isn’t the luxurious place it’s said to be either.

Not that I have a choice now. Pompeii is my home until I’m sold or I die. Or my new master sees fit to free me when I’m no longer of use to him.

Ectur, the monolith of a Parthian tasked with bringing the three of us down from Rome, leads us deeper into Pompeii’s stinking, bustling market. With every exhausted step, our chains rattle over the city’s noise. Though the streets are crowded, people move aside to let us pass. Some give us wary looks, standing between us and their wives and children. Even those struggling to move carts down these difficult roads stay out of our way. They’re especially wary of Ectur. We certainly look the part of gladiators—scarred, tanned brutes, all of us—and since Ectur’s unchained, people probably think he’s our lanista. No citizen with any sense wants near a lanista.

The market must be close to the Forum. All over the place, noblemen strut like cocks and sneer at slaves and citizens, just like every one I ever saw in Rome, as though the gods themselves should fear them. Would’ve liked to have met one of them in the arena during my fighting days; he’d have wept to the gods for mercy, and that pristine white toga would have been stained in shit before I’d fully raised my sword.

But, gods willing, my days in the arena are behind me forever.

Just beyond the market, where the streets fan out toward clusters of high-walled villas, Ectur approaches a squat, balding man in a tunic that’s far too clean to belong to a common laborer. The man’s attention is buried in a beeswax tablet resting on his arm, and he’s muttering to himself as he scratches something into it with a stylus.

He glances up at us, and I realize he only has one eye. Dropping his attention back to the tablet, he grumbles, “Thought you’d leave me waiting all bloody day.”

“Longer journey from Rome than it is from your master’s house,” Ectur mutters.

Without looking up, the one-eyed man says, “I’ll need to look at them before you leave. The Master Laurea will be unhappy if they are not up to his standards.”

Ectur stands straighter, narrowing his eyes. “Caius Blasius doesn’t deal in faulty goods.”

“Then he’ll not mind if I inspect his goods to be sure.” The one-eyed man gestures at us with his stylus. “Whereas I have a beating waiting if I bring to my master slaves who are not to his liking. So he’ll—” He stops abruptly, his eye widening. “Where is the fourth? Master Laurea specifically selected four men, not three.”

“The fourth fell ill. Terrible fever, and the medicus can’t say if he’ll live.” Ectur pulls a scroll from his belt and hands it to the one-eyed man. “Caius Blasius gives his word your master will be compensated.”

Glancing back and forth from the scroll to Ectur, the man sighs heavily. “The master will not be happy. It was the fourth in particular who interested him.”

Ectur sniffs with amusement. “That scrawny Phoenician is hardly worth the sestertii your master paid for him. An entertaining gladiator, maybe, but he’s worthless outside the arena.”

I can’t help a quiet laugh. It’s true enough; the idiot Phoenician is only alive—assuming he still is—because he’s less afraid of his opponents than he is of the punishment for being a coward on the sands. A man bred to be a bodyguard, he is not.

“The master selected his men for a reason,” the one-eyed man snaps at Ectur. He sighs and shakes his head. “Never mind, then. If he isn’t here, he isn’t here. The other three had best be in good condition.”

Ectur doesn’t respond. He folds his arms across his chest, watching with a scowl as the man with the stylus inspects us each in turn, tutting and muttering to himself in between jabbing us with his finger and etching something into the tablet. He pokes at scars and bruises, eyeing us when we flinch, and then checks our teeth and eyes. Since I was a child, I’ve been through more of these inspections than I can count, and still I have to force myself not to put both hands around his throat and show him I’m as fit and strong as a gladiator—or bodyguard, in this case—ought to be.

Finally, he grunts and slams shut the leather cover on the wax tablet. “They’re all well.”

“Good,” says the Parthian. “Give my regards to your master.”

“And yours.” The one-eyed man gestures sharply at us. “Come with me.”

Without a word from any of us, we follow the man. His legs are shorter than ours nearly by half, but he walks quickly, his gait fast and angry, and with heavy chains on our ankles, it’s a struggle to keep up with him. Ectur doesn’t come with us.

Soon, we will meet our new master.

By name, Junius Calvus Laurea isn’t unfamiliar to me. I’ve heard Caius Blasius mention him—usually with a scowl—and he’s apparently bought gladiators from my former master before. I don’t know his face, though, and I know nothing of the man whose life I will be sworn to guard. Only that he isn’t a lanista and my existence no longer includes the inside of an arena. Freedom may not be in my future, but Fortune be praised a thousand times over anyway.

The one-eyed servant leads us down a narrow road between the enormous villas lined up in ranks just inside the wall along the northern edge of the city. In spite of our chains, my fellow former gladiators and I exchange smiles. A villa instead of a ludus gladiatori? Indeed, this will be a new life. The existence of a bodyguard isn’t safe per se, but unless our master has an unusual number of enemies, we’ll protect him with our presence more often than our fighting skills. We’ll more likely die from boredom than a blade.

On our way out of Rome, we’d passed through the shadow of the nearly completed Colosseum. As the immense structure’s cool shade rested on my neck and shoulders, I’d whispered a prayer of thanks, in spite of the chains on my wrists and ankles, for my good fortune. Rumors abound about what’s planned for the Colosseum, and some say the games there will be far greater and more brutal than all the Ludi we’d barely survived at Circus Maximus. Another year or two, people say, and it will be complete. Perhaps I’ll never earn my rudis and the freedom that accompanies it now, but any gladiator should be grateful for the chance to serve a nobleman rather than set foot in that place.

We stop in front of one of the countless villas. There, two massive, heavily-armed guards push open the tall gates, and we walk inside. Our one-eyed guide takes us through the luxurious home to the garden in the back. Here, within the high walls covered in trailing ivy and in the shade of a massive cypress tree, servants and statues surround our new master.

As soon as I see him, I recognize the Master Laurea. I’ve seen him at the ludus before, watching us train and inspecting us the way his servant did today. I didn’t know at the time he was the one called Calvus Laurea, but I never forgot that face. Carved from cold stone, sharply angled, with intense blue eyes that always emphasize the smirk or scowl on his lips.

He lounges across a couch, cradling a polished cup in his hand as a servant fans away the day’s heat with enormous feathers. A large bodyguard stands behind Calvus Laurea, as does a black-eyed servant with a wine jug clutched to her chest.

The man who led us here stops us with a sharp gesture, and all three of us go to our knees, heads bowed.

The master gets up. His sandals scuff on the stone ground. “Stand, all of you.” As one, we rise to attention.

“I am Junius Cal—” His brow furrows. He looks from one of us to the next. Narrowing his eyes, he turns to the man who brought us. “There are three, Ataiun. Where is the fourth?”

The one-eyed servant bows his head. “My apologies, Dominus. There were only three. The fourth was stricken with fever and unable to travel.” He pulls out the scroll Ectur had given him. “His master sends this promise of compensation.”

Master Laurea scowls. “Very well. I suppose it will have to do.” He waves a hand at his servant. “See that it’s accounted for.” To us, he says, “I am Junius Calvus Laurea, and I am your new master.”

Once again, he looks at us each in turn. I try not to notice how his gaze keeps lingering on me longer than it does on the others, but his pauses are too conspicuous to ignore.

At last, he speaks: “You’re the one called Saevius, yes?”

I square my shoulders. “I am, Dominus.”

Without taking his eyes off me, he says to his servant, “Show the others to their quarters.” He gestures at me. “This one stays here.”

The men who accompanied me bow their heads sharply, and a moment later, they are gone.

Master Laurea steps closer to me, still looking me squarely in the eyes. “Welcome to Pompeii, Saevius,” he says with a slight smile. “You may call me Calvus.”

His request for familiarity sends ghostly spiders creeping up the length of my spine.

Without taking his eyes off mine, he snaps his fingers. “Bring us wine. Both of us.”

The servant holding the wine jug obeys immediately, and the spiders are more pronounced now, my breath barely moving as the woman pours two cups of wine. She hands one to our master, and then the other to me.

“Leave us,” Calvus says. “All of you.”

Gods, be with me . . .

In moments, I am alone with my new master, a cup of wine in my uncertain hand. Calvus brings his cup to his lips, pausing to say, “Drink, Saevius. I insist.”

I do. I can’t say if it tastes like the cunt of Venus, but it’s as sweet and rich as Pompeiian wines are said to be, if slightly soured by the churning in the pit of my stomach.

“You won’t be my bodyguard, Saevius,” Calvus says suddenly. “Not like the two who came with you.”

I suddenly can’t taste the wine on my tongue. With much effort, I swallow it. “Whatever you ask of me, Dominus.”

“I have two tasks for you, Saevius.” Something about the way he says my name, the way he keeps saying my name, sends more spiders wandering up and down my back and beneath my flesh. “One simple, one less so.”

I bow my head slightly. “I am here to serve, Dominus.”

“Calvus,” he says. “Call me Calvus.”

I slowly raise my head. “I am here to serve . . . Calvus.”

He grins. “Much better.”

He’s playing a game here. He has to be. What game it is, and what role I play, I can’t work out.

I take another drink of tasteless wine. “What are my duties?”

“There is a ludus gladiatori on the south side of the city.” The mention of a ludus twists something in my chest. Calvus continues, “Your first task is to present a gift to the lanista of that ludus. A gift of five hundred sestertii from Cassius, the city magistrate.” My skin crawls as an odd smile curls the corners of my new master’s mouth. “Cassius deeply regrets he could not present it himself, but”—the smile intensifies—“I promised I would take care of it for him.”

In spite of Calvus’s expression, relief cools my blood. Delivering monetary gifts instead of fighting other gladiators for the entertainment of a roaring crowd? Even if it means setting foot in a ludus again, I’ll be there only as a messenger, not a fighter in training.

Gods, I thank you. Again and again, I thank you.

“Let’s discuss your second task.” He tilts his head just so, like he’s looking for answers to questions he hasn’t yet asked. “Blasius spoke highly of you, Saevius. And your reputation precedes you all the way from Rome.” He raises his cup. “A tremendous fighter, but also a loyal servant.”

He’s quiet for a moment. It’s a silence I’m certain I’m supposed to fill, but I don’t know how.

“Thank you, Dominus,” is all I can think to say, and quickly correct it with, “Calvus. Thank you, Calvus.”

He lowers his wine cup. A different smile forms on his mouth, one that’s taut and unnerving. I’m less and less comfortable as the silence between us lingers.

At last, he speaks, and there’s something in his voice this time, an edge that prickles the back of my neck. “After you’ve delivered the money to the lanista, you will remain at the ludus.” His eyes narrow as one corner of his mouth lifts. “As an auctoratus.”

My heart beats faster. “Dominus, with respect, an auctoratus? I am not a citizen. I’m not even a freedman. How can I be an auctoratus if I am still—”

Calvus puts up a hand. “You will remain my slave, of course, but until such time as I tell you otherwise, you will live at the ludus. Train as a gladiator.” He inclines his head and lowers his voice. “To everyone but us and the gods, and according to the documents that will accompany you, you are a citizen voluntarily submitting to be owned by the ludus and its lanista. Am I understood?”

No. No, what are you asking me to do? And why?

But I nod anyway. “Yes, Dominus.”

He moves now, walking toward, then around me, circling me slowly as he continues speaking. “While you train and fight, you will keep your eyes and ears open. Listen and watch the men around you.”

I sweep my tongue across my dry lips. Every familia gladiatori is already rife with dangerous rivalries. To spy on my brothers within the ludus? Especially when I am the newest blood? I should cut my own throat now and be done with it.

“As an auctoratus,” he says, still walking around me, “you will be able to leave the ludus of your own free will, so long as you return and you don’t leave the city. When I wish to speak to you, I will contact you. Understood?”

“I . . . yes,” I say. “What am I looking for, Dominus? Er, Calvus?”

“You’re a gladiator, Saevius,” he says. “Surely you know how women feel about men like you?”

I nod again. Women were no strangers to the ludus where I trained before. Many of them married, plenty of them noble; my lanista took their money, the women cavorted with gladiators, and the husbands were never the wiser.

“A man of my stature cannot afford the embarrassment of a wife’s . . .” He pauses in both speech and step, wrinkling his nose. “Of a wife’s unsavory indiscretions. Especially with creatures so far below my station.” Calvus resumes his slow, unsettling walk around me. “And when word begins to spread of a woman doing these things, a husband, particularly a husband of my political and social stature, has little choice but to put a stop to it.” He steps into my sight and halts, looking me in the eye. “Which is where you come in, Saevius.”

Oh, dear sweet gods, help me . . .

“You will listen, and you will watch.” Calvus comes closer, eyes narrowing. “Learn the name of the man who keeps drawing my lady Verina into his bed. Am I clear, gladiator?”

In all my years in the arena, my heart has never pounded this hard. What woman doesn’t have slaves as lovers? Gladiators fuck married women as often as we fight amongst ourselves.

Unless Calvus thinks his wife isn’t involved with a slave. One of the freedmen working as trainers? Perhaps the lanista himself? Or one of the munerators renting fighters for some upcoming games? No citizen, especially not a public figure such as Calvus, tolerates that kind of insult from his wife, and for some, divorce isn’t nearly punishment enough.

Regardless of Calvus’s reasoning or what he plans to do once he knows the name of his wife’s lover, is there any place more dangerous for a man than the middle of games played between a wife and the husband she’s scorned?

“Am I clear, gladiator?”

I swallow hard. “Yes, Calvus.”

“Good.” He steps away and lifts his wine again. “I will have your papers drawn up tonight. Tomorrow morning, you will be taken to the ludus owned by the lanista Drusus.”

Drusus. Gods, any lanista but him. I silently beg the ground to open up beneath me. Drusus’s reputation extends beyond any reach Master Calvus could dream of his own doing. No gladiator who’s heard the stories about Drusus would ever volunteer to fight for him.

Calvus looks me up and down, his brow furrowing as he inspects my arms, one then the other. “These scars are . . .” He meets my eyes. “You’re left-handed, aren’t you?”

“I am.”

He grins. “Excellent. I’m sure Drusus will be doubly pleased with you.” The grin widens. “Perhaps I should have chosen you in the first place over that Phoenician. After all, a left-handed fighter like you belongs in the arena where he can make his lanista rich, yes?”

I resist the urge to avoid his eyes.

“You’ll be his left-handed moneymaker, and you’ll—” Calvus gives a quiet, bone-chilling laugh. “Well, I suppose in a way you’ll be my left hand, won’t you?”

“I suppose I will, Dominus,” I whisper.

Calvus puts his hand on my shoulder. The amusement leaves his expression. “Listen closely, gladiator. This is very important. The money you’re giving Drusus, the five hundred sestertii, is from the magistrate called Cassius. The same one who will be providing your auctoratus documents. Is that clear?”

My mouth goes dry as I nod.

“You will not mention me or our arrangement,” he says. “Not to anyone within the ludus under any circumstances. Understood?”

“Yes, Dominus.” I hesitate. “Calvus.”

“Be warned, Saevius. I do not tolerate treachery or dishonesty.” He leans in, lowering his voice so I’m certain no one but me and the gods can hear him, and he presses down hard on my shoulder. “Give me a single reason to believe you’re not doing precisely as I’ve ordered, or that you’ve breathed my name within the walls of the ludus, and I will see to it the magistrate asks Drusus if he received the full seven hundred sestertii. Am I understood?”

With much effort, I swallow. With even more, I nod. “Yes, Calvus.”

And silently, I beg the gods to send me back to Rome to fight in its Colosseum.

All the way through the streets of Pompeii, every scuff of my weathered sandals on the road sounds like the name of my new lanista.

Drusus. Drusus. Any lanista but Drusus.

There isn’t a gladiator in the Empire who hasn’t heard his name. The man’s ill reputation is as widespread as his history is mysterious. Most lanistae begin as fighters themselves, but no one, not even the men who’ve been in the arena for years, can remember seeing him in combat. Some say he must have fought under another name, as many of us do, but no one knows for certain. All that’s known is that he came out of nowhere—seven years ago, people say—and apprenticed under the equally notorious lanista Crispinus for two years. After Crispinus was killed, Drusus took over the ludus. His first order of business? Executing half the men in the familia—by his own hand, most agree—just to flaunt his newfound power. Even more of a madman than most lanistae.

He comes to Rome once or twice a year to buy and sell fighters, and over the years, my old lanista has bought a few of Drusus’s men.

“Scum, that man,” a young fighter had told us. “Even the other lanistae stay away from him. They’d rather wear a curse than be ’round Drusus.”

“The Furies have got nothin’ on Drusus,” another had told us after he’d been with us half a season. “Every man in the familia knew: just look at ’im wrong, and your ass is in the pit and beaten within an inch of your life.” With a shudder, he’d added, “Assuming the bastard didn’t get bored one day and kill you for sport before you even had a chance to make a mistake.”

A scar-covered Egyptian came to us from Drusus and never said a word about the man. But then, that Egyptian never said a word at all. He just stared blankly at his food, his opponent, the wall. Didn’t even bat an eye when the medicus sewed up his arm after the Ludi Florales. About the time he started making some noise and we might’ve gotten some stories out of him, a fighter from Gaul put a sword through him during the Ludi Appollinares. Sometimes I think Fortune was smiling on him that day.

Where are you on this day, Fortune? I silently plead as Ataiun leads me past Pompeii’s immense amphitheatre, the place where fights are held in this city.

Just beyond the amphitheatre, there’s a building I can only assume is Pompeii’s State-run ludus and barracks. I’ve heard the State is swallowing up all the ludi now. In Rome, there’s talk of the State-run ludi being the only ones left in a few years’ time. Maybe this means politicians will one day replace the lanistae as the men who buy, sell, and rent us out. I don’t suppose anyone would notice if they did. Shit replacing shit, after all. Then again, I don’t suppose anyone but men like me will notice when the State takes over the ludus and familia owned by Drusus, anyway.

And may that day come swiftly.

As I walk between two guards, people eyeing us warily and shielding their children, the presence of the scrolls tucked into my belt threatens to burn right through my clothes. These are the documents that will grant me entrance into the ludus. One proclaims I was reinstated as a citizen by Master Blasius after completion of a previous stint as an auctoratus. Another states I was inspected by a medicus I’ve never seen and approved by Cassius, the city magistrate whose monetary gift I carry, to volunteer—again—as an auctoratus. Fake permission all based on a false declaration of freedom.

The scrolls are sealed, and the seals are only to be broken by Drusus himself. I can only hope that the documents are what Calvus says they are, and that they’re convincing forgeries, or it’ll be my throat that’s cut. Though perhaps that wouldn’t be such a bad turn of events.

The ludus that will be my home now is on the other side of the city from my master’s house, past the amphitheatre and near the brothels and taverns. It smells worse than the marketplace out here, and the sounds of fighting and fucking are loud and boisterous even now, just past sunrise.

Over the noise of the drunk and the amorous comes the familiar, rhythmic thwack of wood smacking wood and the clank of metal on metal. Men shouting, grunting, swearing. The crack of a whip, the bark of a trainer.

A busy ludus.

The ludus of the lanista Drusus.

Gods, watch over me . . .

Armed guards stand outside the front gates of the ludus. Mixed blood, both of them, dark skin marred by scars and brands. They’re probably mongrels with ancestors from all corners of the Empire, Gaul to Carthage. Retired gladiators, maybe.

“What’s your business here?” one asks me, his accent thick and unusual.

I glance at one of my escorts. He nods sharply toward the two standing in front of the gate, so I turn to the guards again.

“I’ve come to speak with the Master Drusus.” The words are hot sand on my tongue. “To enlist as an auctoratus.”

“An auctoratus?” The other guard’s eyes dart back and forth between the two men flanking me. “What’s with them, then?”

“He owes our master a debt,” one of my escorts says quickly. “Magistrate’s approved him.” A hand between my shoulders shoves me forward, nearly impaling me on the two spears suddenly pointed at my guts.

I catch my balance and show my palms. The guards hesitate, then draw back their weapons.

“All right, then,” one says. “Come with me.”

He takes me through the gate and hands me off to another weathered foreigner. One of the trainers, if the wooden sword and leather flagellum on his belt are any sign. He gruffly orders the guard back to his post and then leads me across the training yard.

The inside of the ludus isn’t unlike the one where I spent my previous fighting years. Barracks along two sides of a sand-covered training yard. Men sparring. Trainers, some sparring, some watching with flagellum at the ready in case anyone gets out of line.

Heads turn as I’m escorted across the yard. Gladiators are bought and sold all the time, moving from city to city depending on where the auction’s wind blows them, so it’s no surprise I’ve seen a few of their faces before. Some more than others.

One of the trainers watching a pair of fighters—novices, both of them, says their footwork—fought at Circus Maximus a long time ago. I’d recognize those scars and brands anywhere.

Next to that pair of fighters, a lethally quick-footed Egyptian lad spars with a Roman twice his size. The Egyptian sold at an auction earlier this year for a small fortune. We’d all wondered who was willing to pay so much for a single gladiator. Now I know.

I also recognize the bald Parthian by the water trough. He fought for another lanista in Rome until last summer, and I figured he must have died when I didn’t see him at the Ludi Augustales. But he must have been sold to Drusus, and when he sees me, he narrows his eyes and folds his massive arms over the thick scar I left on his chest two summers ago.

Any of these men, any one of them, may be the one who’s bedding the Lady Laurea. By the Furies, when I learn the name of the fighter who’s the reason I’m here, there might well be nothing left for Master Calvus to punish.

We leave the training yard and follow a corridor—much cooler than outside, thank the gods—past the barracks and out into a flat, empty courtyard. On the other side of the courtyard, in the breezeway along the lower floor of a limestone house, we stop outside a closed door. Beyond the door, there’s an argument going on. A loud one.

“You can’t be serious!” shouts an exasperated man.

“Your master wants a fight to the death?” comes the cool response, a calm voice that contrasts sharply with the gruff, gravelly one of the man with whom he argues. Drusus, I assume, and I swear I hear the smirk in his voice as he adds, “Then he’ll pay more.”

“But . . . but . . . Jupiter’s balls, you price-gouging flesh peddler. Gladiators die in the arena all the time!”

“It’s unfortunate.” I can almost see the man shrugging indifferently. “Some live, some die. But a guaranteed fight to the death with one of my gladiators is triple the price of a standard match.”

“Triple? That’s theft!”

“If I wanted to steal your money, I would just steal it instead of engaging in these tiresome negotiations.” Drusus sounds amused, but his voice is still chiseled from cold stone. “Gladiators are expensive, you know. Even the barbarians have to be trained and fed. If you want a guarantee of a dead man at the end of the fight, you’ll damn well pay for the live man I’ll have to purchase and train if mine is the one who loses.”

“And if your man wins?”

“Then the people attending the fight are entertained,” Drusus says, “and the gods are duly honored. The price stands.”

The other man is quiet for a moment, and then releases a sharp, aggravated huff. “Very well. I will let my master know, and if he’s willing to pay your absurd prices, I will return to negotiate a contract.”

“I look forward to it.”

The door flies open. A gray-haired, red-faced man storms out, clutching a tablet to his chest and grumbling to himself.

“Wait here.” My escort steps into the room. A moment later, he re-emerges and sends me in. When the door closes behind me, I’m alone.

No. Not alone. My escort is gone, but I am certainly not alone.

The room is dark except for weak sunlight that squeezes past the single, shuttered window. An oil lamp on a table offers just enough light for me to make out the faces staring silently back at me. A scribe in the corner, propping a tablet on his knee and holding a stylus. Against the back wall stand two immense men who look like they could, without much effort, break any man in the training yard in half.

And sitting in front of the two armed men, leaning on the armrest of a large, ornate chair with a wine cup cradled between his slender fingers, is Drusus.

I gulp.

So this is the mythical Drusus, then. Some legends are wildly exaggerated, but the ones about the man called Drusus are not. Slight in the shoulders and sharp in the eyes, and though he’s seated, I can tell he’s easily a head shorter than me. And just as the legends say, he’s young. He’s no longer a boy, but I can’t imagine it’s been too many summers since he first had to shave the smooth skin across his sharp jaw and cheekbones. I never thought it was possible to consider a lanista beautiful, but it’s hard not to think of Drusus that way, especially compared to all the other lanistae, the grizzled, graying men with bulging bellies and rotting teeth.