Текст книги "Mankillers"

Автор книги: Ken Casper

Жанры:

Исторические приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

His father’s tirade inflamed Buck’s ire. With one hand on the door knob, his voice quivering with rage, he said, “You’re right, Father. I’m not like you or your friends. I don’t believe in owning people or whipping them or killing animals for sport. I want to heal people, not hurt them.” He took a deep breath. “I don’t fit in here and I never will. I’m going to medical school, but I don’t want a penny of your damned blood money. I’ll manage on my own, and you’ll never see me again.”

So much for home sweet home.

#

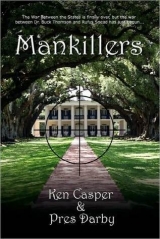

Peering to the end of the broad lane, Buck sat up straight in the saddle and stared, then sagged dejectedly. All that remained of the once beautiful mansion were smoke-tainted red chimneys standing like tombstones in heaps of gray ash.

The semicircle of dilapidated cabins behind the destroyed house was deserted. Shutterless windows stared like dead eyes at the desolation surrounding them. Even the dogs were gone. The only sign of life in the entire compound was a thin thread of smoke curling from the blackened tin pipe of one of the slave shacks. Its front yard was cleared of weeds and shaded by a large chinaberry tree.

Buck rode up slowly, dismounted, and not knowing what to expect, tapped on the porch rail with the barrel of his Colt and held it ready. An entire minute must have elapsed before he heard a mumbled sound from inside, and another minute until finally, a stooped, rail-thin, white-haired Negro woman shuffled barefoot from the dim interior leaning on a gnarled cane. She cupped a veiny hand over rheumy eyes as she stood blinking in the unaccustomed sunlight.

He hardly recognized the woman standing before him. Once strong and stout, she seemed to have shrunken into a wrinkled mummy. She wore a faded gray dress he vaguely remembered as having once belonged to his mother. It was tattered and patched now. The elegant fitted waist hung loose and low, the hem ragged and soiled. He put the gun away.

“Emma, Emma, it’s me, Buck. I’m home.”

“Lord help me, Mr. Buck, I feared I’d never see you again.” She shook her head slowly and lowered herself with Buck’s help into a rickety chair on the porch. “They been bad times ‘round here, bad times.”

He sat on the steps at her feet and held her bony fingers. “What’s happened, Emma? Where is everybody?”

“The black folks, they all run off, Mr. Buck. The white folks, they done gone too. Even the horses . . . been stole or shot.”

He scanned the bleak sight before him and shook his head. Despite his distaste for the injustice and cruelty of the world he’d known here, he couldn’t deny that it had also boasted elegance and beauty. The two-and-a-half-story mansion with its fluted columns, wide piazzas, French windows, expensive furniture, sophisticated décor and carefully collected library had attested to culture and refinement.

“The Yankees do this, Emma? Burn the place, run everybody off?”

“Yessir, but not Yankee soldiers, just bad men. They even burned the cotton seed from meanness, so’s we can’t plant no more.” She looked around suddenly. “Where’s Mr. Clay? He ain’t with you?”

“Clay’s dead, Emma.” Buck said hoarsely. “Killed in the war.”

“Oh God, Oh Jesus, not my baby. Him gone too?” The old woman wailed and beat her chest. “Oh, sweet baby Jesus. Seems like God don’t never stop punishing this poor family.” She rocked back and forth in her chair, humming tunelessly.

“What happened to Father? How did he die?”

“Lord have mercy, child. There’s too much pain, too much. He was pure tired, Mr. Buck. It was all more than a man could take. He wanted to do the right thing. Truly he did, but it was all too much. He just sit on that porch and rock for hours, staring and sipping whiskey. I doesn’t ‘member Mr. Raleigh drinking much before, but he don’t seem to care ‘bout nothing.”

She continued rocking for a long minute, then in a toneless voice began her story.

“It must a been about three days ‘fore General Sherman and his troops got to Columbia. I was setting here on the porch when these men come riding up. They was at least six of ‘em, all dirty and ragged with bushy beards and pistols shoved in they belts. Your momma, she wouldn’t never a let men of that low caliber step foot in the front yard, but she weren’t here. Thank the Lord she didn’t live to see this.”

Buck sat quietly, waiting for her to continue. After a time she did.

“The leader, a scruffy man with a fat belly and a mean mouth, he rode right up to the front steps and yelled ‘Anybody home?’ like he was calling some Jezebel down in a holler. Your poppa, he comes out the door, walking proud like he always do. ‘I’s Raleigh Thomson, sir,’ he say real genteel, like they was gentlemen stopped by for a afternoon a lucre, ‘at your service.’ ‘Anybody else home?’ the fat man say. ‘No sir,’ Mr. Raleigh say back. ‘My wife’s passed and my two boys is . . . away.’ ‘Away fighting with them other Rebs, huh?’ ‘They with the Confederate army,’ your poppa say, standing up straight.”

She rested her head against the back of the chair and closed her eyes, as if she were reliving the sadness of that day.

‘Got any liquor in the house?’ one man yell. Your poppa, he say, ‘No sir, nothing left but a little wine for medicine.’ ‘Well Mr. Reb,’ that fat man say, ‘you set on this here porch while we see what we can find.’ He told one of the men to point a gun on Mr. Raleigh while they went inside. ‘I expect them men was in there over an hour tearing up the place, but they didn’t find nothing they wanted.”

She clamped her jaw at the memory. “So they went and poured coal oil in the house and set it on fire. Oh, Lordy, it blaze up like a pine tree. And Mr. Raleigh, your poppa, he was just standing in the yard with the men watching his house burn—” her voice tightened, as if in misery “—then all sudden-like, he run up the steps and into that fire. I don’t know why he done that, what he was trying to get. I bust out crying then.”

She cried again, a soft keen of pain.

“That fat man, he rode over to where a bunch of us black folk was standing, scared to death, and he yell, ‘You people, get out of here now. You’re free. Understand me? You’re free. Free to go.” Emma sobbed. “One of our men go up to him and say, ‘Yes, sir, but where it is we suppose to go?’”

Tears trickled down the old woman’s wrinkled face as she finished her story. She wiped her eyes on her apron, then cleared her throat and leaned forward again.

“You know, Mr. Buck, things changed ‘round here after your momma passed, and ‘specially after you left. Mr. Raleigh, he lost interest in most everything.” Her tone hardened. “He even bring back that overseer Snead and his brood.”

“Brought Snead back!” Buck exclaimed, barely controlling his rage. “Whatever possessed him to do that?”

She shook her head. “Mr. Raleigh, he needed somebody to run the place. After the fighting started, the new overseer joined the army, and some of the black folks, they just up and left. Your pa knowed Mr. Saul wouldn’t let no more of them run off, so he bring him back, along with them sons of his. Sometime his wife and daughter come here too. They was stealing the place blind, Mr. Buck. That Snead cheated us on weighing our cotton and didn’t credit us like he should. That devil was stealing cotton, selling it hisself and keeping the money that belonged to your poppa. When one of us said he was gonna tell Mr. Raleigh what him and them boys of his was doing, that’s when the bad whippings commenced. I wish you was here to take care of the folks like you done before.”

“But what about Clay?” Buck asked. “Where was he?”

“Oh. He love the place, but he was too young to be running it. Your poppa used to get mad ‘cause he spent most of his time riding that big black horse of his and jumping over them fences . . . and chasing girls.”

She continued to rock back and forth, her lips tightened, and Buck realized she was angry.

“Now that Snead girl, Sally Mae,” the old woman snarled, “she had her eye on him from the minute she got here, pestering him all the time about giving her a ride on that horse. Finally, the day of the big barbecue, after he’d had a bit more whiskey than was fitting a man of his position, well, he swung her up onto the back of that saddle and took off laughing down the avenue, that yellow hair of his streaming out behind him. Must’ve taken her nearabouts to Columbia, ‘cause they don’t come back for more’n a hour. Your pa, he wasn’t happy about such behavior, but that Saul Snead he just grinned.”

“I didn’t even know Saul had a daughter.” Buck shrugged, then asked, “What happened to his family anyhow?”

“Oh, Lordy. Ain’t nothing good happened around here in a long time. Old Saul, he used to beat them sons of his unmerciful, and his wife too. When he found out Sally Mae was with child he commenced beating on her. Rufus tried to protect that poor girl, but old Saul, he turned on the boy with his belt and blinded him in one eye. Rufus was mean before that happened. He was meaner after.”

“What about the girl? What happened to her?”

Emma took a deep breath. “She was carrying that baby inside her, Mr. Buck, but she was doing poorly across the river. One night, real late, I gets a pounding on my door and it’s Rufus, and he’s got the girl in the back of a wagon. From what he said his momma was out somewheres doing Lord knows what, and his poppa, well, he was probably passed out drunk.” All at once Emma’s voice softened.

“Anyways, Rufus, he done seen his sister was getting the pains real bad and he knowed I birthed most all the black babies hereabouts. So he puts her in that wagon and drags her twenty miles to me. Well, that young child, she was already bleeding bad. I done all I knowed how to do, but it wasn’t no good. I got that baby out and breathing, but I couldn’t do nothing for his momma. Rufus, he was real broke up. I reckon Sally Mae was the only person he ever cared about. He took her body back to Lexington that night to bury, but he left the child with me. Before he gone, though, he swore he was gonna kill the man who done that to her.”

“Did he know who it was?”

The old woman turned her head and gazed off into the distance. “There ain’t no telling, Mr. Buck.”

“What happened after that?”

“I heared Mr. Saul’s skinny wife, she run off one night while he was drunk. Nobody seen the boys after that neither. I’m sure glad all of them no-good Sneads is gone.”

“And the baby, Emma? What happened to the baby?”

“Well, sir, I still gots it. Named him Job, since he be having a world of trouble afore him. But I’s raising him best I can.”

Buck remembered then the words in his father’s letter to Clay that he was leaving money for faithful Emma and the child. He hadn’t thought about it at the time. He’d been focused on his father’s affection for his brother, when all he’d had for Buck was respect. Buck would have to take consolation in that.

A scuffling sound came from within the dilapidated cabin.

“Em-ma? Em-ma?” a childish voice called out. A moment later a little white boy appeared in the doorway wearing a much-patched, wrinkled cotton gown and rubbing his eyes. He toddled out onto the porch. The old black woman scooped him up onto her lap with one arm. The child snuggled up against her skinny body, stuck a finger in his mouth and closed his eyes.

Buck saw the genuine affection that passed between them, a child of less than two years and a woman well into old age, though she probably wasn’t more than sixty, rocking contentedly.

“You raising that boy all by yourself, Emma?”

“With the good Lord’s help and my sister’s girl. She done had a baby ‘bout the time this one was born, moved in with me and nursed both of ‘em till it was time for weaning. Then I feeds him soft food.” She cackled. “That weren’t no trouble, since I ain’t got enough teeth left to eat much else. And he sure do like that pot liquor when I cooks greens. Lordy, that’s where all the goodness is. What else was I to do, Mr. Buck? Ain’t nobody else wanted this poor tyke. He ain’t no bother.”

Chapter TWELVE

Buck trotted Gypsy down the familiar sandy road to St Paul’s, the family’s Episcopal Church. His head was reeling with images and recollections of the many hours he’d spent here as a young parishioner and later as an acolyte. In his mind he could see his smiling, animated mother, holding her prayer book, wearing a stylishly elegant wide-hoop skirt and beribboned bonnet, extending her white-gloved hand, palm-down as she greeted neighbors and friends. By her side stood his father, several inches taller, the epitome of the southern gentleman in a finely tailored frock coat and stovepipe hat, a boutonnière in his lapel, shiny black-lacquered walking stick in his gray, kid-gloved grip. He remembered particularly their gracious manners and genteel speech. Sunday services weren’t exclusively for praising the Lord but to celebrate life, a good life for members of the white aristocracy.

This had been part of the world Buck once called home.

The white clapboard church with its stained-glass crusader windows and single towering spire had been built in the 20s, after its predecessor had been destroyed by fire. It needed a fresh coat of whitewash now, but otherwise the provincial house of worship and the rectory a hundred yards to its right appeared to have been spared the ravages of war and foreign invasion. Buck saw no one around, for which he was grateful. He was in no mood for “visiting,” even with old friends. What, after all, would they talk about but casualties, the loss or maiming of brothers, fathers, husbands and other male relations and friends? He’d seen enough of death and mutilation and felt responsible for more than his share of both.

He dismounted and tied Gypsy’s reins to a hitching post, then strode self-consciously to the graveyard between the church and vicarage. He passed by old tombstones with all too familiar names carved into them. Many plots were weed-choked, yet there were several bare mounds scattered about the fenced-in cemetery. Fresh graves. He didn’t bother to read the names on the stakes that served as temporary markers until the ground settled enough for granite stones to be set.

He passed by the Lynch enclosure, noting the names of his mother’s parents, as well as several aunts and uncles and a few cousins who’d died young from whooping cough or measles, but mostly from yellow fever. Proud people who carried themselves with dignity and an inborn sense of noblesse oblige.

He trekked on to the Thomson family enclosure.

Here less pleasant associations crowded his mind . . . poisoned it. The long funeral cortege from Jasmine for his mother’s burial, the lines of black folks, mourning her passing, and crowding up into the gallery of the small church, the unaccustomed smell of whiskey on his father’s breath, eight-year-old Clay crying because his mommy wasn’t with them today.

Buck had no difficulty finding her grave. Her tall, stately tombstone was a kilter. Beside it a subsiding mound was crisscrossed with budding brambles. Only a crude wooden plank with a name and dates scratched inelegantly upon it marked his father’s final resting place. No grand monument. No loving verses or biblical references to eternal life beyond this fragile bar. Buck shook his head. Raleigh Buchanan Thomson had died six months ago. There’d been no one left to order him a tombstone. A detail to attend to later.

He stood over his mother’s grave. “You wouldn’t like the world as it is now, Mother. You left us too soon, but it’s better that you did. I’m afraid you wouldn’t think very highly of me either. I’ll do my best to make amends, if ever I can figure out how. I don’t regret the lives I’ve taken, only the ones I let slip away. As for the others, the ones I mutilated . . . I don’t know what I could have done differently, but I don’t want to do it anymore, ever.”

At last, reluctantly, he turned to his father’s grave. “I never intended to come back, Poppa. And now I wish I hadn’t. I would’ve liked to carry with me the memory of Jasmine as it was, with all its proud vanity and fatal flaws, rather than the blackened ruin it’s become. Like the South itself, Poppa. Proud vanity. Fatal flaws. A blackened ruin. We’ll rise above the ashes. Someday. But it’ll never be the same. We’ll never be the same. I won’t. ”

The lump in his throat burned.

“I’m leaving again, Father, this time for good, now that there’s nothing to come back to. And no one.” His nostrils clogged. He snuffled to clear them. “I failed, Poppa. I was supposed to protect my little brother, and I failed. Clay’s dead. The Cause is dead. Slavery’s dead. Jasmine is no more. It’s all gone, Father.”

Tears coursing down Buck’s face. He made no attempt to brush them away.

“You thought I didn’t love Jasmine, but I did. We just saw it differently, I guess. You saw it the way you thought it had to be, the way it should be. I saw it the way it could have been. Without slavery. Without people being beaten and scarred.” He wiped his cheeks. “It doesn’t matter now. That’s all in the past. You’re gone. Jasmine’s gone, and in a few minutes I’ll be gone too.”

From his coat pocket he removed the plume that had been on Clay’s cavalry hat. The yellow had faded. The blood stains had deepened to a dull brown.

“I have the watch you gave to Clay. If you don’t mind I’m going to keep it. After all it’s not a personal possession as much as a family heirloom. I have a lock of his hair too. The golden boy with the golden hair. A memento of the son who had what you called a reckless exuberance for life. But I’ll leave you this ornament, this last symbol of the boy you sent off to war. I think he might have become a man you could have been proud of, had he lived.”

Again Buck wiped his wet cheeks.

“I forgive you, Poppa, for whatever there is in my power to forgive. I hope before you died, you granted me pardon too for my many offenses.”

He knelt and wedged the damaged tussock into the ground up against the marker, where it might receive some protection from the wind and rain. “That’s all that’s left now, Poppa.” He rose, shook his head and bit his lips. “That’s all that’s left of the world we knew. A wooden board and the broken plumage of a lost cause. May you both rest in peace.”

He nearly ran out of the churchyard, untied Gypsy and sprang into the saddle. He cantered away from the place of his youth, trying to outrun its ghosts.

#

The return journey from Jasmine to Columbia afforded Buck another tour of the detritus of war—fallow fields that had once been rich with cotton, heaps of soot and cinder where proud mansions had stood, more modest piles of ash where slave quarters had clustered. The lower quarter of Richland County might one day recover, Buck ruminated, but that day was far off.

Everything and everyone he’d once held dear was gone. His brother, his father and mother, the plantation that had been his world—they were all faded memories. Only one old black woman, newly up from slavery remained, caring for an abandoned white child. There was nothing and nobody else left to hold Buck Thomson to this place. He renewed his vow to never return.

Summoning to mind what Emma had told him about Saul Snead, he began to appreciate the level of evil that had warped his son. Sadistic beatings that maimed bodies also twisted minds, and like Sherman’s neckties, the straight and narrow, once bent, could never be made functional again. Rufus Snead, the red-headed mankiller, was beyond compassion and pity. His one redeeming feature had been an attempt to protect his sister. But she was dead, and Rufus had abandoned her child. Was that when he became a mankiller? It didn’t matter. Like any rabid dog, the only cure for his malady was a bullet, delivered quickly and painlessly. Buck Thomson, surgeon and expert with firearms, was the man to perform this final amputation of a diseased member from the body social.

Reaching Weston’s Creek, he halted to let Gypsy drink. As he leaned forward to stroke the steed’s neck, the sharp report of a rifle shot from his right was met almost simultaneously with the ricochet of a bullet whining off a granite rock on his left.

Instantly Buck kicked the startled gelding into a full gallop. Thoughts and images tumbled through his mind, all seemingly at once. He wasn’t sure exactly where the bullet had come from, other than the trees to his right. The woods lining both sides of the creek were dense. He needed to pinpoint the shooter’s position, but he didn’t have time. He was a sitting target, fatally vulnerable where he was. Vaulting over a fallen tree as Clay might have done, he tore through a line of thickets onto an open field and glanced behind him. No one was following.

Suppose there was more than one sniper. Suppose another sharpshooter was positioned along his obvious route of escape. There was no cover here. He kicked Gypsy into a faster gallop, and the faithful steed gave him his all.

Only when they reconnected with the meandering road more than a mile later did he rein in the panting horse to an easy trot. By then they’d reached the relative safety of the outskirts ringing the devastated city.

Who’d shot at him and why? Was it a random act of violence brought on by these troubled times, or had he been personally targeted for robbery and perhaps death? Was the sniper another diabolical opportunist, or—

His mind skittered to a halt, while Gypsy continued to dance forward, head high, breathing heavily.

My God, I’ve been a dolt!

Finally, what seemed like isolated, unrelated facts and events began to fit together to form a coherent picture.

His brother Clay had been a womanizer who’d dallied with Sally Mae, Saul Snead’s young daughter. She got pregnant and died in childbirth. Saul’s son, Rufus, swore vengeance against the man who’d taken advantage of her. Clay was later killed, apparently the random target of a redheaded sniper, whom Buck had since been able to identify as Rufus Snead.

Lord, it didn’t take a genius to figure out Clay had been the baby’s father. Why else would an old black woman be raising a little white boy by herself in times that were more precarious than ever slavery had been—except as an act of love and dedication toward the family that had been the focus of her entire life, and the young white man she’d helped raise?

That was the private family matter Clay had wanted to tell Buck about at Sayler’s Creek.

Snead’s finding Lieutenant Clay Thomson in the waning days of the war may have been purely by chance, but Buck was convinced now that his brother’s death hadn’t been the random act of a crazed mankiller. He’d been a carefully and deliberately chosen target for vengeance by the uncle of Clay’s son. A chilling thought struck him.

Now I’m a target too.

#

The sun was low in the summer sky by the time Tracker crossed the river into Lexington County.

A few discreet inquiries had alerted him to the Whiskey Jug Saloon as Rufus Snead’s hangout of choice. Tracker had been there before and knew the place catered to a class of ruffians that didn’t welcome strangers. He had no qualms about invading enemy territory, but this was a reconnaissance mission. He elected to go instead to the Brick Works across the street which welcomed gamblers, drunks and other assorted miscreants.

Wearing a stained and threadbare red frock coat, ruffled white shirt, a pink cravat and a vermillion-plumed straw hat, he held his chin up and traipsed through the front door as if the soles of his scuffed brogans were on fire. Heads turned at his entrance, some in undisguised disgust, others in comical amusement. He could imagine both contingents sharpening their knives or fondling other weapons.

Acting oblivious to their stares and muttered comments, he pranced directly to the long bar and was immediately impressed with the agility of the peg-legged bartender who clumped up and down ceaselessly to serve his thirsty clientele. Tapping his silver-headed walking stick on the scarred mahogany, Tracker said in a voice a little too loud, “I say, my good man, do you serve absinthe?” Simultaneously he clicked two silver dollars together.

Peg-leg’s attention was more focused on the large coins than the question. “Ab-what? We got two kinds of beer and two kinds of whiskey. What’s your pleasure?”

“I really was anticipating an aperitif.” When the bartender tilted his head in annoyance, Tracker added. “A beer, I guess.” He then slid one of the coins to Peg-leg and held his finger on the other. “And a little information?” he said softly.

“Like my whiskey, Mister, I’ll give you your money’s worth.” Peg-leg grinned, displaying large yellow teeth with gaps resembling a smashed picket fence.

“I’m searching for a Snead family from around here somewhere. Are you acquainted with them?”

The men within earshot ceased their chatter.

Peg-leg leaned forward and spoke confidentially. “Now why would a gentleman of your refinement be interested in the likes of them?”

“I met one of them in the war. Said he was from near here.”

An unkempt bearded man seated next to Tracker interrupted. “You don’t want no part of that family, mister, if there’s any of ‘em’s left ‘after what happened.”

“You tell him about it, Cephus,” Peg-leg urged him. “You know the story better than me.” He returned to his clamoring customers, all of whom drank as if they were contestants and the prize was more whiskey.

Seeing his new companion’s glass was empty, Tracker ordered him a fresh drink, and motioned to an unoccupied table along the wall. Once seated, Cephus sniffed the liquor, smiled across to his host, sipped appreciatively, grinned and belched. Tracker grinned too. Apparently Peg-leg had served the barfly the good stuff.

“Now, what can you tell me about the Sneads,” he asked.

Savoring another taste, Cephus began his tale. “Well, sir, since you ain’t from around here, I reckon you need to know that Saul Snead—the daddy of the clan—was the overseer at Jasmine, the Thomson plantation east aways. Had a place of his own too, a few rocky acres up river. His woman farmed it enough to feed herself and her brood, but mostly she made rot-gut whiskey. Sold what the old man didn’t drink and when she could, earned a little extra money on her back, if you get my meaning. Saul ran cock fights too.”

When Cephus finished off what was left in his glass, Tracker waved to Peg-leg to bring him another. “How big a family did Snead have?”

“Well, there was that toothless old woman of his, like I said, and a couple of sorry red-headed sons. All mad as coon dogs, from what I hear, ‘specially when they was drinking. And there was the girl. Hard to imagine them two producing such a purty little thing. Sally Mae they called her. Some say Saul was saving her to snare a rich man.”

Peg-leg brought the whiskey, and Tracker tossed him another silver dollar. “Where’s he now?”

“Well, sir, you won’t believe this, but one night a year or more back neighbors heard awful screaming coming from their place, like a animal being tortured. Next morning a bunch of locals got together, armed themselves real good and rode over to check things out. They couldn’t credit what they seen. That loony Snead had boiled a Negro man to death in his old lady’s big wash pot and was feeding the meat to his dogs. Crazy old coot was eating some of it hisself.”

“My heavens, what’d they do?”

“What any civilized men would. They strung the old bastard up from a tree in his yard. Heard tell, that devil never stopped cussing till the rope jerked tight. Word is them red-headed boys of his rode up a while later, saw their daddy dangling and rode off without even cutting him down. Left him there for the crows. Ain’t no one been out to the place since.” Cephus stared bleary-eyed at Tracker. “If I was you I’d stay clear too. Folks claim the place’s haunted and won’t go near it.” He smacked his lips. “But what I done told you is sure worth another drink, ‘eh, mister?”

Tracker slipped his untouched beer over to him, and feeling generous, ordered another premium whiskey.

“What happened to the rest of the family?” he asked. “His wife?”

“Well, she run off one night. Least ways that’s what Saul said. A few folks think it’s mighty suspicious. I mean why would she do that? Weren’t nobody gonna invite her to go with him, and where would she go? Ain’t got no family she ever talked about. Could have something to do with the girl. Sally Mae got herself in a family way, then died when it was time for the tyke to be born. Some say her momma blamed herself. Others say her poppa blamed her ma and took it out on her. I’ve heard claims that if you dig up the girl’s grave over yonder, you’ll find her momma with her.”

“A terrible tragedy,” Tracker opined.

Peg-leg brought the next installment of conversation enhancer.

“And the sons?”

“Another tragedy,” Cephus declared as he gulped half the newly arrived glass’s contents. “What you might call a i-ron-ic turn of events.”

Over the course of the next hour and several more shots, Cephus told Tracker about Clay Thomson getting Sally Mae pregnant. Sally Mae dying in childbirth. Rufus swearing vengeance on Clay, then finding and killing him during the war.

“Where’d you hear all this?’ Tracker asked casually.

“Here and there. Rufus come back not long ago and told his younger brother Floyd all about it. Right proud he was too.”

“And the irony?” Tracker asked.

It took a moment for the semi-inebriated raconteur to figure out what the question was. “Oh, the i-ron-ic part. Well, seems Rufus and Floyd was riding one day with a couple of friends out by Cedar Creek when Clay’s older brother, Buck—he’s Dr. Thomson now—was passing through. Guess he recognized Rufus, cause he opened fire on him without warning. When the smoke cleared, Floyd and the friend was dead, and Dr. Thomson and his friends was gone.”

Cephus grinned, well pleased with his tale. “The hand of God, some folks ‘round here say. Divine justice, you might call it. Rufus killed Thomson’s brother. Now Thomson’s killed Rufus’s brother.”

“So the feud’s over.”

“Not to hear Rufus talk about it. Buck Thomson killed Floyd, he tells people. Now Rufus has taken over Floyd’s gang and is gonna kill him.”