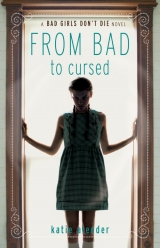

Текст книги " From Bad to Cursed"

Автор книги: Katie Alender

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Lydia was teetering dangerously on the edge of Sunshine Club behavior, and every new request I made threatened to dump her back into Doom Squad territory. But she gave me a pained smile, said, “Wait here,” and headed up the stairs.

I looked around the room and at the dirty floors, imagining what I could do to this place with a few hours and a bucket of bleach. I took a step back and realized that there was something wet and sticky on the tile, right where Lydia had set her grocery bags. I knelt down.

Blood.

Glancing at the stairs, I wondered if I had enough time to get to the kitchen. I took a tentative step but heard Lydia starting her descent. So instead, I tiptoed to the small side table where she’d set her purse and grabbed the piece of paper sticking out of it—what I hoped was her grocery store receipt.

Going against every fiber of my being, I swiped the sole of my shoe across the blood on the floor until it was spread so thinly that you’d never know it was there.

“What are you doing?” Lydia asked, coming around the corner. “Tap dancing?”

“I’m just trying to keep moving,” I said, faking a tense little jig. “I’m nervous. We all are. Or hadn’t you noticed?”

“You know, Alexis, if you aren’t careful, you’re going to wake up one day and realize that you’re no fun to be around.” She pursed her lips. “I can’t find the spell. My room’s kind of a mess. But believe me, I’ll find it. I’m as eager to get this over with as you are. What do you think about having the meeting on Saturday?”

“I guess that’s fine,” I said.

“Now, not to be rude, but could you go? I’m starving.”

I left, but I waited until I was stopped at a traffic light a block away before opening the paper I’d grabbed.

Then I stared at it so long that the cars behind me started honking.

It was a grocery store receipt. The total was $139.24.

And all she’d bought was meat.

“So Lydia’s the new creatura?” Kasey asked, scanning the receipt.

“I guess so. That might explain why she’s been so ragged these days.”

Kasey shot me a wary look. “She looks fine.”

“I’m not being sunshiny. I’m just saying. Protecting the book is a big job. Even Tashi couldn’t handle it.”

“Well, Lydia won’t have to do it for long,” Kasey said.

Lydia had suggested we have the meeting Saturday, assuming someone came through with a new member. Whatever the graduation ceremony involved, we’d get through it. Then Kasey and I would find some excuse to get the book and destroy it.

It was such a simple plan that it kind of made me uneasy, to be honest.

Because nothing with Aralt was ever as simple it seemed.

MY CELL PHONE RANG at 6:30 the next morning. I turned over and answered it without checking to see who was calling.

The voice hit me like a freight train. “Alexis. Where is Tashiana?”

I sat up. “Farrin?”

“She’s not responding to my calls. Have you seen her?”

“No,” I said, rubbing my eyes. “Not this week.”

“Not this week? What do you mean?”

“She left.”

“She left,” Farrin repeated. Something in her voice took me from sleepy to vividly awake.

“Yeah, but it’s okay,” I said. “We still have the book.”

“That’s impossible. Tashiana would never allow the book to be unattended.”

“But…” I didn’t know how to sugarcoat it. “She did.”

“Never,” Farrin said. “She is physically unable to be away from the book for more than a few hours. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

For a moment, I didn’t understand. Then, in a flash, I did.

Tashi was dead. She had to be, if she couldn’t survive apart from the book.

Because it had been at Lydia’s house all week.

But that didn’t seem to be the part that concerned Farrin. “The book is unprotected,” she said. What scared me the most was how quiet her voice became. “The energy is untended. My God, Alexis. What have you girls done?”

“But it’s not untended. It’s…tended,” I said. “There’s a new creatura.”

“Excuse me?”

It felt like every word I said was one more spoonful of dirt out of a giant hole I was digging for myself. But I didn’t know what was wrong with what I was saying, so I didn’t know what not to say.

“There’s a new creatura,” I said. “She’ll look after the book.”

Farrin’s voice dripped acid. “Do you even know what that word means?”

Well—I thought I did. But maybe not. “It’s the creature,” I said. “She takes care of Aralt?”

“Creator, you dumb child!” Farrin snapped. “It’s Latin. Not creature! Creator.”

Creator?

“You can’t have a new creator! She was joined to the book—she was the only one who could properly direct Aralt’s energy. And now you foolish little girls are running around with the potential to completely destroy yourselves.” Then her voice went eerily calm. “Maybe more than just yourselves.”

I was reeling. I couldn’t speak.

We were all doomed.

“I’ll call you back in five minutes. Answer the phone!” Farrin slammed her receiver down so hard it hurt my ear.

Two minutes later the phone rang.

“Here is what you must do,” she said. “There is a spell in the book that you’ll find and read. Every one of you. Write this down. The spell is called Tugann Sibh. Look for those words. Everyone reads it. And one of you must read it twice.”

I went to my desk and wrote it down, fumbling the pen between my clumsy fingers. “Tugann Sibh? What does it mean?”

“Never mind that,” Farrin said. “Just do it.”

“When?”

“As soon as you can,” she said. “Today. And when you are done, bring the book directly to me.”

“I don’t know if I can—I mean, we’ll try. But we don’t have the right number of people yet.”

“There’s no such thing as a right number,” she said. “You’ve got to stop being stubborn and do as I say. Without Tashiana, you and your friends are like a speeding car without a driver. She spent hours each day ensuring that Aralt’s energy flowed properly. Things are bad already—but they could easily get worse.”

All of that power, nothing to guide it. I thought of the force that had battered me in Tashi’s garage, and a chill went up my spine.

“Have you noticed any fluctuations?” she asked. “Besides your disastrous interview and my illness?”

Where would I even start? “Um…maybe one or two,” I said.

“Be careful. You may behave erratically; try to make sure no one gets hurt.”

Oh, sure. Easier said than done.

“This is such an enormous catastrophe,” she said. “I wonder if any of us will be able to recover from it.”

I was too frightened to reply.

“By the way,” she said. “You won the contest. This should have been a great day for you.” She hung up.

No such thing as the right number of people? Then why were we obsessed with getting a new member? Would Adrienne and Lydia really hold the whole process up for another “put your hand on the book” trick?

I sighed and looked down at the words I’d written:

Tugann Sibh.

I dodged Kasey long enough to borrow Mom’s laptop and find the translation on a Gaelic web site: We give.

Give—like a sacrifice?

There was a line in the oath—something about a gift, a treasure.…So what were we giving? Farrin had said one girl had to read the spell twice.

I sat back from the computer in confusion.

Then I remembered the last page of the book—the one covered in signatures. I scrolled through the photos on my phone until I found it. The picture was so blurry I could only make out a few of the names.

But there it was: Suzette Skalaski.

Skalaski. Where had I heard that name before?

In my head, I could hear it spoken in Farrin’s satiny voice…at the mocktail party.

Weatherly College. I turned back to the computer and searched for Suzette Skalaski + Weatherly College.

There was a whole section of the college’s website devoted to the Skalaski School of Photography. At the top was a link labeled OVERVIEW.

The Skalaski School of Photography at Weatherly College was founded in 1988 in honor of Suzette Skalaski, a member of the class of 1974 who passed away before graduation. The state-of-the-art facilities were dedicated at a ceremony attended by California governor George Deukmejian, officiated by Skalaski’s classmate Barbara Draeger, the first female (and youngest) mayor of Las Riveras, California. Another classmate, noted fashion photographer Farrin McAllister, served as a consultant on the building and equipping of the college, and spoke at the dedication. “Suzi was passionate about two things: education and helping others, and to know that this program is made possible in her honor would be among her proudest achievements.”

I found several more references to buildings, scholarships, even a residential street named after Suzette. Finally I found a biography, on her private high school’s “Notable Alumnae” page that gave details about her death: 1973, an aneurysm.

I went back to my phone to look for another name. Even zoomed in all the way, the resolution was so low that it was hard to make them out. The one at the very bottom of the list—the most recent?—looked like “Narelle Simmons.”

I typed it in and hit enter. The first result was a hit: Narelle Simmons, White Pine, Wisconsin.

A blog. The graphic at the top read:

♥♥♥ NARELLE’S WORLD ♥♥♥

Her picture came up in the sidebar. She was a pretty black girl, with short, curly hair and a toothy smile.

Beneath it were three lines of bolded type:

REST IN PEACE

NARELLE DANIQUE SIMMONS

FOREVER IN OUR HEARTS

And then a paragraph telling how the bright, ambitious Narelle had passed away of a brain aneu-rysm.

I stared breathlessly at the screen.

One more. The next name I could make out was “Marnie Peterson.”

There were too many results, so I went back and made it Marnie Peterson + dead teenager.

I clicked on an article from the Palm Beach Post, dated five years earlier.

Area teens and parents are distraught over the sud den death of Guacata High School junior Marnie Peterson. Principal Helen Fritsch said that Peterson had begun her high school career as a problem student but had recently turned her life around and begun committing to both her studies and her future. Grief counselors will be available at the school. Peterson’s cause of death was reported as…

An aneurysm.

Farrin stood over a tray of chemicals, tongs in hand, watching a print.

“How can I help you, Alexis?” she said.

“So you sort of left out a minor detail,” I said, trying to keep my voice level.

“What’s that?”

“Oh, you know. Just that somebody dies.”

There was a cold, mocking edge to her voice. “I wouldn’t have thought you’d have a problem with it. Tashiana’s death didn’t seem to disturb you.”

That wasn’t true—or fair. I was horrified by Tashi’s death. I just knew I didn’t have time to let the horror of it get to me.

“The way you said it—I could have just picked someone at random—and they would have died. Because of me.” I tried to suppress the anger I felt when I thought that I might have asked Megan—or Emily—or—

“Well, it won’t be random now. Is that a comfort?”

“No!” I said. “I don’t see why someone else should have to die. And why didn’t you tell me last night?”

“You didn’t ask.”

“I can’t do it,” I said, bringing my fist down on the counter. “I won’t. How can you say being popular or getting out of a few parking tickets is worth a human being dying?”

She hadn’t moved. “You’re still not getting it, Alexis,” she said gently.

“But don’t you feel bad?” I asked. “Suzette Skalaski died for you. And you get to drive a Mercedes. Congratulations.”

She actually laughed—a harsh, short laugh. “I can assure you that Suzette did not die so I could drive a luxury car.”

“Then why?”

Farrin turned away from her print. “Listen to me. Listen very carefully.”

Oh, I was listening, all right.

“Suzette sacrificed herself because she wanted to.”

The phrase hit me like a physical blow.

“Alexis, for thousands of years, men have been throwing themselves in front of cannons and arrows so that some king could own another few million acres and grow richer off the taxes.”

“That still doesn’t make it right.”

“When Suzette gave her life for us, she was giving to a cause greater than herself. Suzette’s friends have gone on to be senators, to win Oscars—”

“And Pulitzers?” I interjected.

She nodded. “Yes. And to make incredible medical discoveries, to create timeless sculptures. Every day we’re alive, with everything we do, we all pay tribute to her sacrifice.”

“Yeah, but what did she get out of it?” I asked.

“Have you ever sacrificed for someone you cared about?” she asked. “Have you ever traded one important thing so another important thing could thrive?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

All of my problems seemed to have started because I wasn’t willing to do that.

“Beauty. Popularity. Winning the contest. Getting a full scholarship to Weatherly College,” she said, her eyebrow arched. “Those are only external things. But Alexis, what about your injured finger? What about the way you think and react when you trust in Aralt?”

All of those good grades, charmed teachers. The cut that had disappeared from my hand. Even the burns from the curling iron were healing quickly—though the healing seemed to start and stop at random intervals.

“It would be selfish to keep such blessings to one small group of people. So when the time comes, one of your friends—or it could even be you—will volunteer, make a gift of her own life force so Aralt can keep going, keep helping others. It replenishes his strength.”

I closed my eyes. “That’s so wrong.”

“Why?” she asked. “If Suzette was happy to do it, why should we not accept her painless, happy death as the generous and precious gift it was?”

“That’s horrible,” I said. “It’s not worth a life.”

“Easy for you to say,” she said, rearing her head back. “You’re a confident, talented, healthy young woman. But what about the others?”

Healthy—that made me think of Adrienne. How she was next in line for her mother’s disease and wheel-chair-bound existence.

“All I’m saying,” Farrin said quietly, “is that maybe it doesn’t seem like a very significant thing to you. But there are others for whom it is quite a big deal.”

Would Adrienne really let someone die so she could stay out of a wheelchair?

“Dr. Jeanette Garzon discovered a treatment for a genetic disorder that has saved the lives of thousands of children,” Farrin said. “Jeanette was a freshman at Weatherly when Suzi, Barbara, and I were juniors. She was dirt-poor and in danger of losing her scholarship.”

I stared at the floor.

“Ask the parents of the children Jeanette has saved,” Farrin said. “Ask the children themselves. If it’s worth the death of one willing person so that they all might be alive today.”

“But maybe if she hadn’t gotten into medical school, someone else would have, and maybe they would have discovered the cure to a totally different disease.”

Farrin lifted her chin. “You can’t live according to theoretical models, Alexis. You can only make the most of the opportunities you’ve been given.”

I sat back and sighed. “But if Tashi’s really—gone, then who’s going to manage the energy?”

Farrin turned away. “That does complicate things. But we have no reason to believe that we can’t keep the book in a safe place and continue to benefit from Aralt’s generosity.”

“Not send it to a new group of girls?” I asked. “Then…no one else would die.”

“I suppose not,” Farrin said. “We couldn’t risk sending the book out without Tashiana. Does that make it easier for you?”

“No,” I said, trying to sound more sure than I was.

“Anyway, the simple fact is, you have no options other than Tugann Sibh. You’re incredibly lucky that such a simple solution exists. You would be wise not to question it.”

“If I weren’t one of Aralt’s girls,” I said, “would I still have won the contest?”

She didn’t look up from her work. “But you are one of Aralt’s girls.”

“But if I weren’t.”

She finished clipping the print over the air vent and turned to me. “Alexis, with your camera, you can change the world. You can affect the way people think. You can fight wars and end them. You can make heroes and destroy them. You can shine a light on injustice. It’s not just doctors who make a difference.”

I thought about that—finding something I cared about and bringing out passion in other people. For a treacherous moment, I was filled with a lustrous feeling of power.

“But I don’t—I mean, I do want to achieve things. But not because of some magical ring. Not because someone died for it.”

“Aralt isn’t a genie in a bottle. I’ve worked hard, very hard, to get where I am. And you will have to work hard too. But when you do the work, you will see the results. That’s all.”

I was starting to get a headache.

She came toward me and grabbed my hands. “This is your destiny, Alexis. Embrace it.”

“No.” I backed away. “I can’t. I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry is not an option.” Her fingers were still wrapped around my own. “You don’t have a choice.”

“I do,” I said. “We could just not do anything. Or we could get rid of the book.”

In the dark, with the red light behind her, her eye sockets were shadows. Her hair was a mass of blackness outlined by a red halo. “Now don’t go doing anything foolish.”

I swallowed hard, fighting the urge to back away. “No, I mean, give it back to you.”

She relaxed. “You’re so smart,” she said, twisting the word derisively. “Why don’t you go home and research the South McBride River incident?”

She followed me out through the workroom, though in a way it felt like I was being chased out. As she held the door open, she looked down her nose at me.

“You have a responsibility, Alexis. Remember that.”

I ran out to the parking lot, huffing and puffing painfully by the time I got to Mom’s car.

Stuck beneath the windshield wiper, flapping in the wind, was a parking ticket.

I drove straight to the library.

In the summer of 1987, a group of sixteen high school girls in the town of South McBride River, Virginia, were all struck with a debilitating mental illness. The most accepted theory was that the girls had somehow stirred up some toxic sludge from the bottom of a local lake, exposing them to a previously unknown bacterium. The infection shut down their brain functions and left them all comatose. One by one, they died.

There were entire websites devoted to it, most of them set up by conspiracy theorists, who pinned it on everything from aliens to a deliberate government effort. One man had somehow gotten hold of the girls’ school records, showing that every one of them, even the most mediocre students, had finished the school year with straight A’s. He went on to say that, in the depths of their madness, several of them carved the word ARALT into their bodies. This, he claimed, was an acronym for the U.S. government’s top-secret “Advanced Research in Atomic and Laser Technology” department.

So the door to Aralt, once opened, must be closed again or you’ll be driven insane, and then your brain will turn to useless mush.

I sat back against the hard wood of the library chair, feeling this new information like a twenty-pound weight on my chest.

We had to read that spell. One of us had to die…or we’d all die anyway.

I WENT STRAIGHT HOME, got in bed, and stared at the ceiling. I didn’t answer my phone. I lied to my parents about feeling sick, and I ignored Kasey when she tried to talk to me. Finally, teary-eyed with hurt, she got the idea and left me alone.

Tashi was dead.

We were all bound to an incredibly selfish and angry spirit.

And the only way to fix it was for someone else to die.

I kept feeling this weird urge to just act normal, to pull the covers up to my chin and try to get some sleep. Wake up and have everything be fine. Just an ordinary day.

That is never going to happen, I told myself. You are never going to have another normal day. Unless you find some way to stop this, you will never be normal again.

* * *

The orange glow of the sodium halide streetlights mixed with the shadows of tree branches on my wall.

I ran through everything I could remember about the book, about Aralt, about Tashi. Especially Tashi. That night I’d been there, she’d been afraid. Why? Had it been Lydia at the door? Why had she pushed me into the garage?

I need to show you, she’d said.

Show me that Aralt was evil?

Because she’d known someone was going to die? But women had been dying for more than a century for Aralt. There had to be a hundred and fifty signatures on those pages. What was different now? What had changed?

And I kept repeating her last words to me: Try again.

Elspeth had said so too. Try again.

But try what again?

The Ouija board?

I got up and reached under my bed, where I’d hidden it. I sat on the floor and set the board up in a patch of bright orange light.

“Tashi?” I whispered. “Can you hear me? I’m sorry you died. I need your help.…I don’t understand what it was that you wanted me to try.”

No response.

“Elspeth?” I whispered. Then, helplessly, “Anyone?”

The pointer gave a quick jerk, startling me. I pulled my hands off and watched it move. It seemed to swing, more than wobble—great sweeping motions, full of purpose, like a pendulum.

I-A-M-H-E-R-E

“Elspeth?” I asked.

But I knew it wasn’t Elspeth.

Slowly, I reached down, intending to upturn the board, breaking the connection, and fold it up before any more words came out.

But as my hands got closer, the planchette stood perfectly still.

Was he gone?

I slooooowly lowered my fingers toward the pointer.

Just before I touched it, it bubbled up with inky black goo.

I tried to grab my hand away, but I was too late—

In a fraction of a second, it exploded into a sheet of black that stretched to cover my whole body like a cocoon. I opened my mouth to scream, and it poured in through my lips, silencing me. It was as sticky and impenetrable as a giant spiderweb. I tried to pound against it with my fists, but with every move I made, it squeezed and constricted me more. As it thickened over my eyes and my ears, I lost my balance and fell sideways onto the carpet.

Within a minute, my whole world was contained in a shrinking womb of black webbing. I could breathe, but I couldn’t hear my own breath. I couldn’t see or move.

I lost track of how long I lay there, driven into a frenzy of fear but bound as tightly as a straitjacketed mental patient. I knew I was sobbing, and I could feel the vibrations of moaning in my throat, but all sound was silenced by the impassible shroud.

There was no such thing as time, or light, or movement.

Only darkness as endless as death.

Finally, mercifully, I lost consciousness.

I awoke—how much later?—on the floor. My whole body shook as the memory pounced on me. Had I dreamed it? The Ouija board was on the carpet by the window. My fingernails had dug bright red half-moons in my palms. The wounds stung in the open air.

And I was thirsty. God, I’d never been so thirsty.

There was a cup of water on my nightstand. I downed it in one long swig. That did nothing to soothe my parched throat, so I went to the kitchen and filled and emptied the cup twice more.

I was unsteady on my feet, like I’d had too much cold medicine. I had to lean against the counter to keep my balance.

Then I went to the bathroom and washed my hands, noting how filthy my fingernails were. I found the nailbrush under the sink and scrubbed until the tips of my fingers were pink and almost raw. At first, dark red liquid—my own blood, from my torn-up palms—ran from them. But then the water ran clear, and there were still black crescents under my nails. They wouldn’t come clean.

I flipped on the light and studied myself. Aside from my palms and my fingernails, there was no evidence that I’d just been attacked.

I leaned toward the mirror and opened my mouth.

The sight made me stagger backward into the wall behind me.

The whole inside of my mouth was charcoal black, as dark as the inside of the cocoon. My teeth, my tongue, my gums…as far down my throat as I could see—black.

Collecting myself, I leaned in closer and noticed a gray overlay covering the whites and irises of my eyes, as thin as a pair of sheer black panty hose. I blinked a few times, but couldn’t feel it—thank God.

I wasn’t in pain. Actually, considering everything I’d just been through, I felt pretty okay.

I turned off the bathroom light and went back to the kitchen, filling my cup again. I left it on the counter so I could come back and get it. The energy seemed to be draining out of me. The thought of climbing back into my bed filled me with a sense of almost giddy anticipation.

To stretch out and feel the smooth, soft sheets against my arms, the coolness of the pillowcase against my face—to sink into a sweet, sumptuous sleep—

But not yet. There would be time for that later.

First, I had to kill my sleeping family.