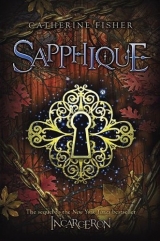

Текст книги "Sapphique"

Автор книги: Kathryn Fisher

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

He wanted to say something comforting, but the horse was restless, stamping its impatience, and in the Prison death had been too familiar to feel strange now. Controlling the horse, he brought it back round to her. ‘Jared is brilliant, Claudia. He’s far too clever to be controlled by the Queen, or anyone else. Don’t worry. Trust him’

‘I told him I did.’ Still she didn’t move. He reached out and caught her arm.

‘Come on. We need to hurry’ She turned and looked at him. ‘You could have killed Giles.’

‘I should have. Keiro would despair. But that boy is not Giles. I am.’ He met her eyes. ‘Standing there with that pistol pointed at me, I knew. I remembered, Claudia. I remembered.’ She stared at him, astonished.

Then the horse whinnied, and they saw the lights of the Court, all its hundreds of candles and lanterns and windows flicker and go out. For a whole minute the Palace was a blackness under the stars. Claudia held her breath. If they didn’t come back on . . . If this was the end.

Then the Palace was blazing again.

Finn held out his hand. ‘I think you should give me Incarceron.’ She hesitated. Then she drew out her father’s watch and handed it to him, and he held up the silver cube, so that it spun on its chain. ‘Keep it safe, sire.’

‘The Prison is drawing power from its own systems.’ He glanced down at the Palace, where a clamour of bells and shouts had begun to ring out.

‘And from ours,’ Claudia whispered.

‘You can’t. Rix, you can’t.’Attia’s voice was earnest and low, anything to keep him calm. ‘It’s ridiculous. I worked for you – we went against that gang of bandits together, that mob in the plague village. You liked me. We got on. You can’t hurt me:

‘You know a few too many secrets, Attia.’

‘Cheap tricks! Cons. Everybody knows them’ It was the real sword, not the collapsible one. She licked sweat from her lip.

‘Well maybe.’ He pretended to consider, and then grinned.

‘But you see, it’s the Glove. Stealing that was unforgivable.

The Glove is telling me to do it. So I’ve decided you’ll go first, and then your friend there can watch. It’ll be quick, Attia. I’m a merciful man.’ Keiro was silent, as if he was leaving this to her. He had given up on the knots. Nothing would undo those in time.

Attia said, ‘You’re tired, Rix. You’re mad. You know it.’

‘I’ve walked a few wild Wings.’ He swept the sword experimentally through the air. ‘I’ve crawled a few crazy corridors.’

‘Talking of which,’ Keiro said suddenly, ‘where’s that pack of freaks you usually travel with?’

‘Resting.’ Rix was working himself up. ‘I needed to move fast.’ He swung the sword again. There was a sly light in his eye that terrified Attia. His voice was slurred with ket.

‘Behold!’ he muttered. ‘You search for a Sapient who will show you the way Out. I am that man!’ It was the patter of his act. She struggled, kicking, jerking against Keiro. ‘He’ll do it. He’s off his skull!’ Rix swung to an imaginary crowd. ‘The way that Sapphique took lies through the Door of Death. I will take this girl there and I will bring her back!’ The fire crackled. He bowed to its applause, to the ranks of roaring people, held up the sword in his hand. ‘Death.

We fear it. We would do anything to avoid it. Before your eyes, you will see the dead live.’

‘No.’ Attia gasped. ‘Keiro …’ Keiro sat still. ‘No chance. He’s got us.’ Rix’s face was flushed in the red light; his eyes bright as if with fever. ‘I will release her! I will bring her back!’ With a whipping slash that made her gasp the sword was raised, and at the same time Keiro’s voice, acid with scorn and deliberately conversational, came from the darkness behind her.

‘So tell me, Rix, since you seem to think you’re Sapphique.

What was the answer to the riddle you asked the dragon?

What is the Key that unlocks the heart?’

23

He worked night and day. He made a coat that would transform him; he would be more than a man; a winged creature, beautiful as light. All the birds brought him feathers. Even the eagle. Even the swan.

LEGENDS OF SAPPHIQUE

Jared was sure he was still delirious. Because he lay in a ruined stable and there was a fire, crackling loudly in the silent night.

The rafters were a mesh of holes above his head, and in one place a barn owl stared down with wide astonished eyes.

From somewhere water dripped. The splashes landed rhythmically just beside his face, as if after some great rainstorm. A small pool had formed, soaking into the straw.

Someone’s hand lay half out of the blankets; he tried absently to make it move, and the long fingers cramped and stretched. It was his, then.

He felt disconnected, only vaguely interested, as if he had been out of his body on some long and tiring journey.

As if he had come home to find the house cold and comfortless.

His throat, when he remembered it, was dry His eyes itched. His body, when he moved it, ached.

And he must be delirious because there were no stars.

Instead, through the broken roof of the building a single red Eye hung huge in the sky, like the moon in some livid eclipse.

Jared studied it. It stared back, but it wasn’t watching him.

It was watching the man.

The man was busy. Over his knees he had some old coat – a Sapient robe, perhaps – and on each side of him rose a great stack of feathers. Some were blue, like the one Jared had sent through the Portal. Others were long and black, like a swan’s, and brown, an eagle’s plumage.

‘The blue ones are very useful: the man said, without turning. ‘Thank you for them.’

‘My pleasure,’ Jared murmured. Each word was a croak.

The stable was hung with small golden lanterns, like the ones used at Court. Or perhaps these were the stars, taken down and propped here and there, hung on wires. The man’s hands moved swiftly. He was sewing the feathers into the bare patches of the coat, fixing them first with dabs of pitchy resin that smelt of pine cones when it dripped on the straw. Blue, black, brown. A coat of feathers, wide as wings.

Jared made an effort to sit up, and managed it, propping himself dizzily against the wall. He felt weak and shaky.

The man put the coat aside and came over. ‘Take your time. There’s water here.’ He brought a jug and cup, and poured. As he held it out Jared saw that the right forefinger of his hand was missing; a smooth scar seamed the knuckle.

‘Only a little, Master. It’s very cold.’ Jared barely felt the shock to his throat. As he drank he watched the dark-haired man and the man stared back, a rueful, sad smile.

‘Thank you.’

‘There’s a well just near here. The best water in the Realm.’

‘How long have I been here?’

‘There’s no time here, remember. Time seems to be forbidden in the Realm.’ He sat back, and there were feathers stuck to him, and his eyes were steady and obsessive as a hawk’s.

‘You are Sapphique,’ Jared said quietly.

‘I took that name in the Prison.’

‘Is that where we are?’ Sapphique pulled plumage from his hair. ‘This is a prison, Master. Whether it’s Inside or Out, I’ve learnt, is not really important. I fear they both may be the same.’ Jared struggled to think. He had been riding in the Forest.

There were many outlaws in the Forest, many woodwoses and madmen. Those who couldn’t bear the stagnation of Era, who wandered as beggars. Was this one of them?

Sapphique sat back, his legs stretched out. In the firelight he was young and pale, his hair lank with the forest—damp.

‘But you Escaped,’ Jared said. ‘Finn has told me some of the tales they tell about you in there, in Incarceron.’ He rubbed at his face and found it rough, faintly stubbled. How long had he been here?

‘There are always stories.’

‘They’re not true?’ Sapphique smiled. ‘You’re a scholar, Jared. You know that the word truth is a crystal, like the Key. It seems transparent, but it has many facets. Different lights, red and gold and blue, flicker in its depths. Yet it unlocks the door.’

‘The door. . . You found a secret door, they say.’ Sapphique poured more water. ‘How I searched for it. I spent whole lifetimes searching. I forgot my family, my home; I gave blood, tears, a finger. I made myself wings and I flew so high the sky struck me down. I fell so far into the dark that there seemed no ending to the -abyss. And yet in the end, there it was, a tiny plain door in the Prison’s heart.

The emergency exit. Right there all the time.’ Jared sipped the cold water. This must be a vision, like Finn had in his seizures. He himself was probably lying delirious now in the dark rainy woodland. And yet could it be so real?

‘Sapphique .. . I must ask you...’

‘Ask, my friend.’

‘The door. Can all the Prisoners leave by it? Is that possible?’ But Sapphique had gathered the feathered coat and was examining its holes. ‘Each man has to find it himself, as I did.’ Jared lay back. He tugged the blanket around him, shivering and tired. In the Sapient tongue he said softly, ‘Tell me, Master, did you know Incarceron was tiny?’

‘Is it?’ Sapphique replied in the same language, his green eyes as he looked up lit by deep points of flame. ‘To you, perhaps. Not to its Prisoners. Every prison is a universe for its inmates. And think, Jared Sapiens. Might not the Realm also be tiny, swinging from the watchchain of some being in a world even vaster? Escape is not enough; it does not answer the questions. It is not Freedom. And so I will repair my wings and fly away to the stars. Do you see them?’ He pointed, and Jared drew in a breath of awe, because there they were, all around him, the galaxies and nebulae, the thousands of constellations he had so often watched through the powerful telescope in his tower, the glittering brilliance of the universe.

‘Do you hear their song?’ Sapphique murmured.

But only the silence of the Forest came to them, and Sapphique sighed. ‘Too far away. But they do sing, and I will hear that music.’ Jared shook his head. Weariness was creeping over him, and the old fear. ‘Perhaps Death is our escape

‘Death is a door, certainly.’ Sapphique stopped threading a blue feather and looked at him. ‘You fear death, Jared?’

‘I fear the way to it.’ The narrow face seemed all angles in the firelight. It said, ‘Don’t let the Prison wear my Glove, use my hands, speak with my face. Whatever you have to do, do not allow that.’ There were so many questions Jared wanted to ask. But they scuttled away from him like rats into holes and he closed his eyes and lay back. Like his own shadow, Sapphique leant beside him.

‘Incarceron never sleeps. It dreams, and its dreams are terrible. But it never sleeps.’ He barely heard. He was falling down the telescope, through its convex lenses, into a universe of galaxies.

Rix blinked.

He paused, barely for a second.

Then he slashed the sword down. Attia flinched arid screamed but it whistled behind her and sliced the ropes that held her to Keiro, nicking her wrist so that it bled. ‘What the hell are you doing?’ she gasped, scrambling away.

The magician didn’t even look at her. He pointed the trembling blade at Keiro. ‘What did you say?’ If Keiro was amazed he didn’t show it. He stared straight back, and his voice was cool and careful. ‘I said, what’s the Key that unlocks the heart. What’s the matter, Rix? Can’t answer your own riddle?’ Rix was white. He turned and walked in a rapid circle and came back. ‘That’s it. It’s you. It’s you!’

‘What’s me?’

‘How can it be you? I don’t want it to be you! For a while I thought it might be her: He jabbed the blade at Attia. ‘But she never said it, never came near saying it!’ He paced another frantic circle.

Keiro had drawn his knife. Hacking at the ropes on his ankles he muttered, ‘He’s barking.’ No. Wait.’ Attia watched Rix, her eyes wide. ‘You mean the Question, don’t you? The Question you once told me only your Apprentice would ever ask you. That was it? Keiro asked it?’

‘He did.’ Rix couldn’t seem to keep still. He was shivering, his long fingers gripping and loosening on the swordhilt. ‘It’s him. It’s you.’ He tossed the sword down and hugged himself. ‘A Scum thief is my Apprentice:

‘We’re all scum,’ Keiro said. ‘if you think...’ Attia silenced him with a glare. They had to be so t careful here.

He undid the ropes and stretched his feet out with a grimace. Then he leant back and she saw he understood. lie smiled his most charming smile. ‘Rix. Please sit down.’ The lanky magician collapsed and huddled up like a spider. His utter dismay almost made Attia want to laugh aloud, and yet she felt sorry for him. Some dream that had kept him going for years had come true, and he was devastated in his disappointment.

‘This changes everything.’

‘I should think so.’ Keiro tossed the knife to Attia. ‘So I’m the sorcerer’s apprentice, am I? Well, it might come in useful.’ She scowled at him. Joking was stupid. They had to use this.

‘What does it mean?’ Keiro leant forward, his shadow huge on the cave wall.

‘It means revenge is forgotten.’ Rix stared blankly into the flames. ‘The Art Magicke has rules. It means I have to teach you all my tricks. All the substitutions, the replications, the illusions. How to read minds and palms and leaves. How to disappear and reappear.’

‘How to saw people in half?’

‘That too.’

‘Nice.’

‘And the secret writings, the hidden craft, the alchemies, the names of the Great Powers. How to raise the dead, how to live for ever. How to make gold pour from a donkey’s ear.’ They stared at his rapt, gloomy face. Keiro raised an eyebrow at Attia. They both knew how precarious this was.

Rix was unstable enough to kill; their lives depended on his whims. And he had the Glove.

Gently she said, ‘So we’re all friends again now?’

‘You!’ He glared at her. ‘Not you!’

‘Now now, Rix.’ Keiro faced him. ‘Attia’s my slave. She does what I say.’ She swallowed her fury and glanced away. He was enjoying this. He would tease Rix within inches of Insanity; then grin and charm the danger away. She was trapped here between them, and she had to stay, because of the Glove.

Because she had to get it before Keiro did.

Rix seemed sunk in torpor. And yet after a moment he nodded, muttered to himself and went to the waggon, tugging things out.

‘Food?’ Keiro said hopefully.

Attia whispered, ‘Don’t push your luck.’

‘At least I have luck. I’m the Apprentice, I can twist him round my finger like flexiwire.’ But when Rix came back with bread and cheese Keiro ate it as gratefully as Attia, while Rix watched and chewed ket and seemed to recover his gap—toothed humour. ‘Thieving not paying well these days then?’ Keiro shrugged.

‘All the jewels you carry; Sacks of loot.’ Rix sniggered. Fine clothes.’ Keiro fixed him with a cold eye. ‘So which is the tunnel we leave by?’ Rix looked at the seven slots. ‘There they are. Seven narrow arches. Seven openings into the darkness. One leads to the heart of the Prison. But we sleep now. At Lightson, I take you into the unknown.’ Keiro sucked his fingers. ‘Anything you say, boss.’ Finn and Claudia rode all night. They galloped down the dark lanes of the Realm, clattering over bridges and through fords where sleepy ducks flapped from the rushes, quacking.

They clopped through muddy villages where dogs barked and only a child’s eye at the edge of a lifted shutter watched them go by.

They had become ghosts, Claudia thought, or shadows.

Cloaked in black like outlaws, they fled the Court, and behind them there would be uproar, the Queen furious, the Pretender vengeful, the servants panicked, the army being ordered out.

This was rebellion, and nothing would be the same now.

They had rejected Protocol. Claudia wore the dark breeches and coat and Finn had flung the Pretender’s finery into the hedge. As the dawn began to break they topped a rise and found themselves high above the golden countryside, the cocks crowing in its pretty farmyards, its picturesque hovels glowing in the new light.

‘Another perfect day: Finn muttered.

‘Not for long maybe. Not if Incarceron has its way.’ Grimly, she led the way down the track.

By midday they were too exhausted to go on, the horses stumbling with weariness. At an isolated byre shadowed by elms they found straw heaped in a dim sun-slanted loft, where dull flies buzzed and doves cooed in the rafters.

There was nothing to eat.

Claudia curled up and slept. If they spoke, she didn’t remember it.

When she woke it was from a dream of someone knocking insistently at her door, of Alys saying, ‘Claudia, your father’s here. Get dressed, Claudia” And then soft in her ear, Jared’s whisper: ‘Do you trust me, Claudia?’ With a gasp she sat upright.

The light was fading. The doves had gone and the barn was silent, with only a rustle in the far corner that might have been mice.

She leant back, slowly, on one elbow.

Finn had his back to her; he slept with his body curled up in the straw, the sword by his hand.

She watched him for a while until his breathing altered, and although he didn’t move, she knew he was awake. She said, ‘How much do you remember?’

‘Everything.’

‘Such as?’

‘My father. How he died. Bartlett. My engagement with you.

My whole life at Court before the Prison. In snatches

… foggy, but there. The only thing I don’t know is what happened between the ambush in the Forest and the day I woke in the Prison cell. Perhaps I never will.’ Claudia drew her knees up and picked straw from them.

Was this the truth? Or had it become so necessary for him to know that he had convinced himself?

Maybe her silence revealed her doubts. He rolled over.

‘Your dress that day was silver. You were so small – you wore a little necklace of pearls and they gave me white roses to present to you. You gave me your portrait in a silver frame.’ Had it been like silver? She had thought gold.

‘I was scared of you.’

‘Why?’

‘They said I had to marry you. But you were so perfect, and shining, your voice was so bright. I just wanted to go and play with my new dog’ She stared at him. Then she said, ‘Come on. They’re probably only hours behind.’ Usually it took three days to travel between the Court and the Wardenry; but that was with inn stops, and carriages.

Like this it was a relentless gallop, sore and weary and stopping only to buy hard bread and ale from a girl who came running out from a decaying cottage. They rode past watermills and churches, over wide downs where sheep scattered before them, through wool-snagged hedges, over ditches and the wide grassgrown scars of the ancient wars.

Finn let Claudia lead. He no longer knew where they were, and every bone in his body ached with the strain of the unaccustomed riding. But his mind was clear, clearer and happier than he ever remembered. He saw the land sharp and bright; the smells of the trampled grass, the birdsong, the soft mists that rose from the earth seemed new things to him. He dared not hope that the fits were over.

But perhaps his memory had brought back some old strength, some certainties.

The landscape changed slowly. It became hilly, the fields smaller, the hedges thick, untrimmed masses of oak and birch and holly. All night they rode through them, down lanes and bridlepaths and secret ways as Claudia became more and more certain of where she was.

And then, when Finn was almost asleep in the saddle, his horse slowed to a halt, and he opened his eyes and looked down on an ancient manor house, pale in the glimmer of the broken moon, its moat a silver sheen, its windows lit with candles, the perfume of its ghostly roses sweet in the night.

Claudia smiled in relief. ‘Welcome to the Wardenry.’ Then she laughed ruefully. ‘I left in a carriage full of finery to go to my wedding. What a way to come back Finn nodded. ‘But you still brought the Prince,’ he said.

24

People will love you f you tell them of your fears.

THE MIRROR OF DREAMS TO SAPPHIQUE

‘Well?’ Rix grinned. With a showman’s flourish he pointed to the third tunnel from the left.

Keiro walked over to it and peered in. It seemed as dark and smelly as the rest. ‘How do you know?’

‘I hear the heartbeat of the Prison.’ There was a small red Eye just inside each of the tunnels.

They all watched Keiro.

‘If you say so.’

‘Don’t you believe me?’ Keiro turned. ’Like I said, you’re the boss. Which reminds me, when do I start my training?’

‘Right now.’ Rix seemed to have got over his disappointment. He had a self-important air this morning; he took a coin out of the air before Keiro’s eyes, spun it, and held it out to him. ‘You practise moving it between your fingers like this. And so. You see?’ The coin rippled between his bony knuckles.

Keiro took it. ‘I’m sure I can manage that:

‘You’ve picked enough pockets to be deft, you mean.’ Keiro smiled. He palmed the coin, then made it reappear.

Then he ran it pleasantly through his fingers, not as smoothly as Rix but far better than Attia could have done.

‘Room for improvements’ Rix said loftily. ‘But my Apprentice is a natural.’ He turned away, ignoring Attia completely, and strode into the tunnel.

She followed, feeling gloomy and a little jealous. Behind her the coin tinkled as Keiro dropped it, and swore.

The tunnel was high, its smooth walls perfectly circular. It was lit only by the Eyes, which were placed at regular intervals in the roof, so that the red glow of one was distant before the next made their shadows loom on the floor.

‘Are you watching us so closely?’ Attia wanted to ask. She could feel Incarceron here, its curiosity; its need, breathing in her ear, like a fourth walker in the shadows.

Rix was far in front, with a bag on his back and the sword, and somewhere, hidden on his person, the Glove. Attia had no weapons, nothing to carry. She felt light, because everything she knew or owned had been left behind, in some past that was slipping from her mind. Except Finn. She still carried Finn’s words like treasure in her hands. I haven’t abandoned you.

Keiro came last. His dark red coat was torn and ragged but he wore a belt with two knives from the waggon stuck in it and he had scrubbed his hands and face and tied up his hair.

As he walked he tipped the coin between his fingers, tossed it and caught it, but all the time his blue eyes were fixed on Rix’s back. Attia knew why. He was still smarting at the loss of the Glove. Rix might no longer want revenge, but she was sure Keiro did.

After hours she realized the tunnel was narrowing. The walls were appreciably closer, and the colour of them was changing to a deep red. Once she slipped, and looking down, saw that the metal floor was wet with some rusty liquid, running from the gloom ahead.

It was just after that that they found the first body.

It had been a man. He lay sprawled against the tunnel wall, as if washed there by some sudden flood, his crumpled torso barely more a rag-hung skeleton.

Rix stood over it and sighed. ‘Poor human flotsam. He came farther than most.’ Attia said, ‘Why is it still here? Not recycled?’

‘Because the Prison is preoccupied with its Great Work.

Systems are breaking down.’ He seemed to have forgotten he wasn’t speaking to her any more.

As soon as he had walked on, Keiro muttered, ‘Are you with me or not?’ She scowled. ‘You know what I think about the Glove.’

‘That’s a no then.’ She shrugged.

‘Suit yourself. Looks like you’re back being the dog– slave.

That’s the difference between us.’ He walked past her and she glared at his back.

‘The difference between us; she said, ‘is that you’re arrogant Scum and I’m not.’ He laughed, and tossed the coin.

Soon there was debris everywhere. Bones, carcasses of animals, wrecked Sweepers, tangled masses of crumpled wires and components. The rusty water flowed over them, deeper now, and Incarceron’s Eyes saw everything. The travellers picked their way through, the water knee-high, and flowing fast.

‘Don’t you care?’ Rix snapped suddenly, as if his thoughts had burst out of him. He was gazing down at what might have been a halfman, its metallic face grinning up through the water.

‘Don’t you feel for the creatures that crawl in your veins?’ Keiro’s hand was at his sword but the words were not for him. The answer came as laughter; a deep rumble that made the floor shake and the lights flicker.

Rix paled. ‘I didn’t mean it! No offence Keiro came up and grabbed him. ‘Fool! Do you want it to flood this and sweep us all away!’

‘It won’t do that.’ Rix’s voice was shaky but defiant. ‘I have its greatest desire

‘Yes and if you’re dead when you deliver it what does Incarceron care? Keep your mouth shut!’ Rix stared at him. ‘I’m the master. Not you.’ Keiro pushed past him and waded on. ‘Not for long.’ Rix looked at Attia. But before she could speak, he hurried on.

All day the tunnel narrowed. After about three hours the roof was so low that Rix could stretch up and touch it. The flow of the water was a river now; objects were washed down in it, small Beetles and tangles of metal. Keiro suggested a torch, and Rix lit one reluctantly; in its acrid smoke they saw that the walls of the tunnel were covered with scum, a milky froth obliterating graffiti that seemed to have been there for centuries – names, dates, curses, prayers. And there was a sound too, thudding softly for hours before Attia was aware she could hear it, a deep, pounding shudder, the vibration that she had felt in her dream in the Swan’s Nest.

She came up to Keiro as he stood listening. In front of them the tunnel shrank into the dark.

‘The heartbeat of the Prison,’ she said.

‘Shush...’

‘Surely you can hear it?’

‘Not that. Something else.’ She kept silent, hearing only the wading sloshes of Rix behind them, weighed down by his pack. And then Keiro swore, and she heard it too. With an unearthly screech a flock of tiny blood-red birds shot out of the tunnel, splitting in panic, so that Rix ducked.

Behind the birds, something vast was coming. They couldn’t see it yet, but they could hear it; it scraped and sheared against the sides, as if it was metal, a great tangle of sharpness, a mass forced down by the current. Keiro swung the torch, scattering sparks; he scanned the roof and the walls. ‘Back! It’ll flatten us!’ Rix looked sick. ‘Back where?’ Attia said, ‘There’s nowhere. We have to go ahead.’ it was a hard choice. And yet Keiro didn’t hesitate. I Ic raced into the dark, stumbling in the deep water, the torch shedding burning pitch like stars into the torrent. I’he roar of the approaching object filled the tunnel; ahead in the darkness Attia could see it now, an enormous ball of tangled wires, red light faceted from its angles as it rolled towards them.

She grabbed Rix and hustled him on, straight into the path of the thing, knowing it was death, huge, a pressure wave building in her ears and throat.

Keiro yelled.

And then he disappeared.

It was so sudden, like a magic trick, that Rix howled in anger and she almost stumbled, but then she was floundering towards the spot, and the rumble of the great mesh ball was on her, over her, above her.

A hand shot out.

She was hauled sideways and she fell, deep in the water, Rix crashing over her. Then arms went round her waist and hefted her aside, and the three of them felt the scorching heat as the object sheared past them, its blades scraping sparks from the walls. And she saw there were drowned faces in it; rivets and helmets and coils of wire and candlesticks. It was a compacted sphere of ore and girders, impaling a thousand coloured rags, a million scraps of steel flaking off in its wake.

As it passed she felt the friction, the condensed air imploding in her eardrums. It filled the tunnel fully; it scraped itself by with a million screeches and the darkness stank of scorching.

And then it was wedged tight in the dark, filling the world, and her knee was aching, and Keiro was picking himself up and swearing furiously at the state of his coat.

Attia stood, slowly.

She was deafened and stunned; Rix looked dazed.

The torch was out, floating in the thigh-high water, and there was no Eye here, but gradually she made out the dim shape of this fork in the tunnel that had saved them.

Ahead was a red glow.

Keiro slicked back his hair.

He looked up at the crushed and tangled surface of the sphere; it shuddered, the force of the water juddering it against the constricting walls.

There was no way back now. Over the noise he yelled something, and though Attia couldn’t hear it, she knew what it was. He pointed ahead, and waded on.

She turned, and saw Rix reaching out to touch something that glared out from the metal, and she saw it was a mouth; the open snarling maw of a great wolf, as if some statue had been swept away in there, and was struggling to get out.

She pulled at his arm. Reluctantly, he turned away.

I want the drawbridge up.’ Claudia marched along the corridor shedding her coat and gloves. ‘Archers in the gatehouse, on every roof, on the Sapient’s tower.’

‘ Master Jared’s experiments . . .’ the old man muttered.

‘Pack the delicate things and get them down in the cellars.

Ralph, this is F– Prince Giles. This is my steward, Ralph...’ The old man bowed deeply, his arms full of Claudia’s scattered clothes. ‘Sire. I am so honoured to welcome you to the Wardenry. I only wish...’

‘We haven’t got time.’ Claudia turned. ‘Where’s Alys?’

‘Upstairs, madam. She arrived yesterday, with your messages. Everything has been done. The Warden’s levies have been raised. We have two hundred men billeted in the stable-block and more are arriving hourly.’ Claudia nodded. She flung open the doors of a large, wood-panelled chamber. Finn smelt the sweetness of roses outside its open casements as he strode in after her. ‘Good.

Weapons?’

‘You’ll need to consult with Captain Soames, my lady. I believe he’s in the kitchens.’

‘Find him. And Ralph.’ She turned. ‘I want all the servants assembled in the lower hail in twenty minutes.’ He nodded, his wig slightly askew. ‘I’ll see to it.’ At the door, just before he bowed himself out, he said, ‘Welcome back, my lady. We’ve missed you.’ She smiled, surprised. ‘Thank you.’ When the doors were closed Finn went straight to the cold meats and fruit laid out on the table. ‘He won’t be so pleased when the Queen’s army comes over the horizon.’ She nodded, and sat wearily in the chair. ‘Pass me some of that chicken.’ For a while they ate silently. Finn gazed round at the room, its white plaster ceiling pargeted with scrolls and lozenges, the great fireplace with the emblems of the black swan. The house was calm, the stillness drowsy with bees and the sweetness of roses.