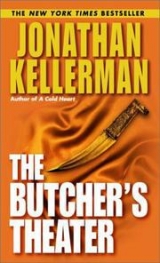

Текст книги "The Butcher's Theatre"

Автор книги: Jonathan Kellerman

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 41 страниц)

After that he cut himself from time to time. On purpose-he was the boss over the knives. Little tiny cuts that didn't bleed for long, notches nicked into the tops of his fingernails. There was a squeezing tool in the case, off to one side, and he used it to squeeze his finger until it turned purple and hot and throbbing and he couldn't stand it any longer. He used tissues to soak up the blood, collected the bloody pieces of paper, and hid them in a toy box in his closet.

After playing with the knives, he sometimes went up to his room, locked the door, and took out nail files, scissors, safety pins, and pencils. Laying them out on his own desk, slapping together clay people and doing operations on them, using red clay for blood, making sarcoma holes and butthole flowers, cutting off their arms and legs.

Sometimes he imagined the clay people screaming. Loud, wiggly screams of Oh, no! and Oh, my god! Chopping off their heads stopped that.

That'll show you to scream!

He played with the knives for weeks before finding the knife book.

The knife book had no people in it, just drawings of knives and tools. A catalog. He turned pages until he found drawings that matched the knives in the black leather case. Spent a long time finding matches, learning the names and memorizing them.

The seven ones with the short blades were called scalpels.

The folding one on top with the little pointed blade was a lancet.

The ones with the long blades were called bistouries.

The skinny, round things were surgical needles.

The sharp spoon was a probe and scoop.

The one that kind of looked like a fork with two points was a probe-detector.

The hollow tube was a cannula; the pointy thing that fit into it was a trocar.

The fat one with the thick, flat blade was a raspatory.

The squeezing one off on the side, by itself, was a harelip clamp.

At the bottom of the case was his favorite one. It really Bade him feel like the boss, even though he was still scared to pick it up, it was so big and felt so dangerous.

The amputating knife. He needed two hands to hold it steady. Swing it in an arc, a soft, white neck its target.

Cut, slice.

Oh, god!

That'll show you.

There was other neat stuff in the library too. A big brass microscope and a wooden box of prepared slides-flies' legs that looked like hairy trees, red blood cells, flat and round like flying saucers. Human hair, bacteria. And a box of hypodermic needles in one of the desk drawers. He took one out, unwrapped it, and stuck it in the back of one of the leather chairs, on the bottom, next to the wall, where no one would notice it. Pretending the chair was an animal, he gave it shots, jabbing the needle in again and again, hearing the animal screaming until it turned into a person-a naked, ugly person, a girl-and started screaming in words.

Oh, no! Oh, god!

"There!" Jab. "That'll show you!" Twist.

He stole that needle, took it up to his room, and put it in with the bloody tissues.

A neat room. Lots of neat stuff.

But he liked the knives the best.

More interviews, more dead ends; five detectives working like mules.

Lacking any new leads, Daniel decided to retrace old ones. He drove to the Russian Compound jail and interviewed Anwar Rashmawi, concentrating on the brother's final conversation with Issa Abdelatif, trying to discern if the boyfriend had said anything about where he and Fatma had stayed between the time she'd left Saint Saviour's and the day of her murder. If Abdelatif's comment about Fatma's being dead had been more specific than Anwar had let on.

The guard brought Anwar in, wearing prison pajamas three sizes too big for him. Daniel could tell right away the brother was different, hostile, no longer the outcast. He entered the interrogation room swaggering and scowling, ignored Daniel's greeting and the guard's order to sit. Finally the guard pushed him down into the chair, said, "Stay there, you," and asked Daniel if there was anything more he needed.

"Nothing more. You may go."

When they were alone, Anwar crossed his legs, sat back in his chair, and stared at the ceiling, either ignoring Daniel's questions or turning them into feeble jokes.

Quite a change from the puff pastry who'd confessed to him two weeks ago. Bolstered, no doubt, by what he imagined to be hero status. According to the guards, his father had been visiting him regularly, the two of them playing sheshbesh, listening to music on Radio Amman, sharing cigarettes like best pals. The old man smiling with pride as he left the cell.

Twenty fruitless minutes passed. The room was hot and humid. Daniel felt his clothes sticking to him, a tightness in his chest.

"Let's go over it again," he said. "The exact words."

"Whose exact words?"

"Abdelatifs."

"Snakes don't talk."

Like a broken record.

Daniel opened his note pad.

"When you confessed, you said he had plenty to say. I have it here in my notes: ' he started to walk toward me with the knife, saying I was dead, just like Fatma. That she was nothing to him, garbage to be dumped.' You remember that, don't you?"

"I remember nothing."

"What else did he say about Fatma's death?"

"I want my lawyer."

"You don't need one. We're not discussing your crime, only Fatma's murder."

Anwar smiled. "Tricks. Deceit."

Daniel got to his feet, walked over to the brother, and stared down at him.

"You loved her. You killed for her. It would seem to me you'd want to find out who murdered her."

"The one who murdered her is dead."

Daniel bent his knees and put his face closer to Anwar's. 'Not so. The one who murdered her has murdered again– he's still out there, laughing at all of us."

Anwar closed his eyes and shook his head. "Lies." 'It's the truth, Anwar." Daniel picked up the copy of Al fajr. waved it in front of Anwar's face until his eyes opened, and said, "Read for yourself."

Anwar averted his gaze.

"Read it, Anwar."

"Lies. Government lies."

"Al Fajr is a PLO mouthpiece-everyone knows that, Anwar. Why would the PLO print government lies?"

'Government lies."

"Abdelatif didn't murder her, Anwar-at least not by himself. There's another one out there. Laughing and plot-ing.'

'I know what you're doing," said Anwar smugly. "You're trying to trick me."

'I'm trying to find out who murdered Fatma."

"The one who murdered her is dead."

Daniel straightened, took a step backward, and regarded the brother. The stubbornness, the narrowness of vision, tightened his chest further. He stared at Anwar, who spat on the floor, played with the saliva with the frayed toe of his shoe.

Daniel waited. The tightness in Daniel's chest turned hot, a fiery band that seemed to press against his lungs, branding them, causing real, searing pain.

"Idiot," he heard himself saying, words springing to his lips, tumbling out unfettered: "I'm trying to find the one who butchered her like a goat. The one who sliced her open and scooped out her insides for a trophy. Like a goat hanging in the souq, Anwar."

Anwar covered his ears and screamed. "Lies!"

"He's done it again, Anwar," Daniel said, louder. "He'll keep doing it. Butchering."

"Lies!" shouted Anwar. "Filthy deceit!"

"Butchering, do you hear me!"

"Jew liar!"

"Your revenge is incomplete!" Daniel was shouting too. "A dishonour upon your family!"

"Lies! Jew trickery!"

"Incomplete, do you hear me, Anwar? A sham!"

"Filthy Jew liar!" Anwar's teeth were chattering, his hands corpse-white, clutching his ears.

"Worthless. A dishonour. A joke for all to know." Daniel's mouth kept expectorating words. "Worthless," he repeated, looking into Anwar's eyes, making sure the brother could see him, read his lips. "Just like your manhood."

Anwar emitted a wounded, rattling cry from deep in his belly, jumped out of the chair, and went for Daniel's throat. Daniel drew back his good hand, hit him hard against the face with the back of it, his wedding ring making contact with the eyeglasses, knocking them off. A follow-up slap, even harder, rasping the bare cheekbone, feeling the shock of pain as metal collided with bone, the frailty of the other man's body as it tumbled backward.

Anwar lay sprawled on the stone floor, holding his chest and gulping in air. A thick red welt was rising among the crevices and pits of one cheek. An angry diagonal, as if he'd been whipped.

The door was flung open and the guard came in, baton in hand.

"Everything okay?" he asked, looking first at Anwar hyper-ventilating on the floor, then at Daniel standing over him, rubbing his knuckles.

"Just fine," said Daniel, breathing hard himself. "Everything's fine."

"Lying Jew dog! Fascist Nazi!"

"Get up, you," said the guard. "Stand with your hands against the wall. Move it."

Anwar didn't budge, and the guard yanked him to his feet and cuffed his hands behind his back.

"He tried to attack me," said Daniel. "The truth upset him."

"Lying Zionist pig." An obscene gesture. "QusAmakr Up your mother's cunt.

"Shut up, you," said the guard. "I don't want to hear from you again. Are you all right, Pakad?"

"I'm perfectly fine." Daniel began gathering up his notes.

"Finished with him?" The guard tugged on Anwar's shirt collar.

"Yes. Completely finished."

He spent the first few minutes of the ride back to Headquarters wondering what was happening to him, the loss of control; suffered through a bit of introspection before putting it aside, filling his head instead with the job at hand. Thoughts of the two dead girls.

Neither body had borne ligature marks-the heroin anesthesia had been sufficient to subdue them. The lack of struggle, the absence of defense wounds suggested they'd allowed themselves to be injected. In Juliet's case he could understand it: She had a history of drug use, was accustomed to combining narcotics with commercial sex. But Fatma's body was clean; everything about her suggested innocence, lack of experience. Perhaps Abdelatif had initiated her into the smoking of hashish resin or an occasional sniff of cocaine, but intravenous injection-that was something else.

It implied great trust of the injector, a total submission. Despite Anwar's craziness, Daniel believed he'd been telling the truth during his confession. That Abdelatif had indeed said something about Fatma being dead. If he'd meant it literally, he'd been only a co-participant in the cutting. Or perhaps his meaning had been symbolic-he'd pimped his ewe to a stranger. In the eyes of the Muslims, a promiscuous girl was as good as dead.

In either event, Fatma had gone along with the transaction, a big jump even for a runaway. Had the submission been a final cultural irony-ingrained feelings of female inferiority making her beholden to a piece of scum like Abdelatif, obeying him simply because he was a man? Or had she responded to some characteristic of the murderer himself? Was he an authority figure, one who inspired confidence?

Something to consider.

But then there was Juliet, a professional. Cultural factors couldn't explain her submission.

During his uniformed days in the Katamonim, Daniel had gotten to know plenty of prostitutes, and his instinctual feelings toward them had been sympathetic. They impressed him, to a one, as passive types, poorly educated women who thought ill of themselves and devalued their own humanity. But they disguised it with hard, cynical talk, came on tough, pretended the customers were the prey, they the predators. For someone like that, surrender was a commodity to be bartered. Submission, unthinkable in the absence of payment.

Juliet would have submitted for money, and probably not much money. She was used to being played with by perverts; shooting heroin was no novelty-she would have welcomed it.

An authority figure with some money: not much.

He put his head down on the desk, closed his eyes, and tried to visualize scenarios, transform his thoughts into images.

A trustworthy male. Money and drugs.

Seduction, rather than rape. Sweet talk and persuasion– the charm Ben David had spoken of-gentle negotiation, then the bite of the needle, torpor, and sleep.

Which, despite what the psychologist had said, made this killer as much a coward as Gray Man. Maybe more so, because he was afraid to face his victims and reveal his intentions. Hiding his true nature until the women lost consciousness. Then beginning his attack in a state of rigid self-control: precise, orderly, surgical. Getting aroused by the blood, working himself up gradually, cutting deeper, hacking, finally losing himself completely. Daniel remembered the savage destruction of Fatma's genitals-that had to be the orgasmic part, the explosion. After that, the cool-off period, the return of calm. Trophy-taking, washing, shampooing. Working like an undertaker. Detached.

A coward. Definitely a coward.

Putting himself in the killer's shoes made him feel slimy. Psychological speculation, it told him nothing.

Who, if you were Fatma, would you trust to give you an injection?

A doctor.

Where would you go if you were Juliet and needed epilepsy medicine?

A doctor.

The country was full of doctors. "We've got one of the world's highest physician-to-citizen ratios," Shmeltzer had reminded him. "Over ten thousands of them, every goddamned one of them an arrogant son of a bitch."

All those doctors, despite the fact that most physicians were government employees and poorly paid-an experienced Egged bus driver could earn more money.

All those Jewish and Arab mothers pushing their sons.

The doctors they'd spoken to had denied knowing either girl What could he do, haul in every M.D. for interrogation?

On the basis of what, Sharavi? A hunch?

What was his intuition worth, anyway? He hadn't been himself lately-his instincts were hardly to be trusted.

He'd been waking at dawn, sneaking out the door each morning like a burglar. Feasting on failure all day, then coming home after dark, not wanting to talk about any of it, escaping to the studio with graphs and charts and crime statistics that had nothing to teach him. No daytime calls to Laura. Eating on the run, his grace after meals a hasty insult to God.

He hadn't spoken to his father since being called to view Fatma's body-nineteen days. Had been an absymal host to Gene and Luanne.

The case-the failure and frustration so soon after Gray Man-was changing him. He could feel his own humanity slipping away, hostile impulses simmering within him. Lashing out at Anwar had seemed so natural.

Not since the weeks following his injury-the surgeries on his hand, the empty hours spent in the rehab ward-had he felt this way.

He stopped himself, cursed the self-pity.

How self-indulgent to coddle himself because of a few weeks of job frustration. To waste time when two women had been butchered, God only knew how many more would succumb.

He wasn't the job; the job wasn't him. The rehab shrink, Lipschitz, had told him that, trying to break through the depression, the repetitive nightmares of comrades exploding into pink mist. The urge, weeks later, to hack off the pain-racked, useless hunk of meat dangling from his left wrist. To punish himself for surviving.

He'd avoided talking to Lipschitz, then spilled it all out one session, expecting sympathy and prepared to reject it. But Lipschitz had only nodded in that irritating way of his. Nodded and smiled.

You're a perfectionist, Captain Sharavi. Now you'll need to learn to live with imperfection. Why are you frowning? What's on your mind?

My hand.

What about it!

It's useless.

According to your therapists, more compliance with the exercise regimen would make it a good deal more useful.

I've exercised plenty and it's still useless.

Which means you're a failure.

Yes, aren't I?

Your hand's only part of you.

It's me.

You're equating your left hand with you as a person.

(Silence.)

Hmm.

Isn't that the way it is in the army? Our bodies are our tools. Without them we're useless.

I'm a doctor, not a general.

You're a major.

Touche, Captain. Yes, I am a major. But a doctor first. If it's confidentiality you're worried about-

That doesn't concern me.

I see Why do you keep frowning? What are you feeling at this moment!

Nothing.

Tell me. Let it out, for your own good Come on, Captain.

You're not

I'm not what!

You're not helping me.

And why is that!

I need advice, not smiles and nods.

Orders from your superiors!

Now you're mocking me.

Not at all, Captain. Not at all. Normally, my job isn't to give advice, but perhaps in this case I can make an exception.

(The shuffling of papers.)

You're an excellent soldier, an excellent officer for one so young. Your psychological profile reveals high intelligence, idealism, courage, but a strong need for structure-an exter-nally imposed structure. So my guess is that you'll stay in the military, or engage in some military-like occupation.

I've always wanted to be a lawyer.

Hmm.

You don't think I'll make it?

What you do is up to you, Captain. I'm no soothsayer

The advice, Doctor. I'm waiting for it.

Oh, yes. The advice. Nothing profound, Captain Sharavi, just this: No matter what field you enter, failures are inevitable. The higher you rise, the more severe the failure. Try to remem-ber that you and the assignment are not the same thing. You're a person doing a job, no more, no less.

That's it?

That's it. According to my schedule, this will be our last session. Unless, of course, you have further need to talk to me.

I'm fine, Doctor. Good-bye.

He'd hated that psychologist; years later, found him prophetic.

The job wasn't him. He wasn't the job.

Easy to say, hard to live.

He resolved to retrieve his humanity, be better to his loved ones, and still get the job done.

The job. The simple ones solved themselves. The others you attacked with guesswork masquerading as professionalism.

Doctors. His mind kept returning to them, but there were authority figures besides doctors, others who inspired obedience, submission.

Professors, scientists. Teachers, like Sender Malkovsky– the man looked just like a rabbi. A man of God.

Men of God. Thousands of them. Rabbis and sheikhs, imams, mullahs, monsignors and monks-the city abounded in those who claimed privileged knowledge of sacred truths. Spires and steeples. Fatma had sought refuge among their shadows.

She'd been a good Muslim girl, knew the kind of sympathy she could expect from a mullah, and had run straight to the Christians, straight to Joseph Roselli. Was it far-fetched to imagine Christian Juliet doing the same?

But Daoud's surveillance had revealed no new facts about the American monk. Roselli took walks at night; he turned back after a few minutes, returned to Saint Saviour's. Strange, but nothing murderous. And phone calls to Seattle had turned up nothing more ominous than a couple of arrests for civil disobedience-demonstrations against the Vietnam War during Roselli's social-worker days.

Ben David had raised the issue of politics and murder, but if there was some connection there, Daniel couldn't see it.

During the daylight hours Roselli stayed within the confines of the monastery, and Daniel alternated with the Chinaman and a couple of patrol officers in looking out for him. It freed the Arab detective for other assignments, the latest of which had nearly ended in disaster.

Daoud had been circulating in the Gaza marketplace, asking questions about Aljuni, the wife-stabber, when a friend of the suspect had recognized him, pointing a finger and shouting "Police! Traitor!" for all to hear. Despite the unshaven face, the kaffiyah and grimy robe, the crook remembered him as "that green-eyed devil" who had busted him the year before on a drug charge. Gaza was rife with assassins; Daniel feared for his man's life. Aljuni had never been a strong possibility anyway, and according to Daoud, he stayed at home, screaming at his wife, never venturing out for night games. Daniel arranged for the army to keep a loose watch on Aljuni, requested notification if he traveled. Daoud said nothing about being pulled off the assignment, but his face told it all. Daniel assured him that he hadn't screwed up. that it happened to everyone; told him to reinterview local villagers regarding both victims, and save his energies for Roselli.

If it bothered Daoud's Christian conscience to be tailing a man of the cloth, his face didn't show it.

Malkovsky, the other paragon of religious virtue, was under the surveillance of Avi Cohen. Cohen was perfect for the assignment: His BMW, fancy clothes, and North Tel

Aviv face blended in well at the Wolfson complex; he could wear tennis clothes, carry a racquet, and no one would give it a second thought.

He was turning out to be an okay kid, had done a good job on Yalom and on Brickner and Gribetz-avoiding discovery by the slimy pair, making detailed tapes and doing the same for Malkovsky.

But despite the details, the tapes made for boring lis-tening The day after Daniel confronted him, the child raper spent hours traipsing around the neighborhood with four of his kids, tearing handbills off walls, throwing the scraps in paper bags, careful not even to litter.

According to Cohen, he was rough on the kids, yelling at them. ordering them around like a slavemaster, but not mistreating them sexually.

Once the handbills were taken care of, his days became predictable: Early each morning he went to shaharit minyan at the Prosnitzer rebbe's yeshiva just outside Mea She'arim, driving a little Subaru that he could barely fit into, staying within the walls of the yeshiva building until lunchtime. A couple of times Avi had seen him walking with the rebbe, looking ill at ease as the old man wagged his finger at him and berated him for some lapse of attention or observance. At noon he came home for lunch, emerged with food stains on his shirt, pacing the halls and wringing his hands.

"Nervous, antsy," Avi said into the recorder. "Like he's fighting with his impulses."

A couple more minutes of pacing, then back into the Subaru; the rest of the day spent hunched over a lectern. Returning home after dark, right after the ma'ariv minyan, no stop-offs for mischief.

Burying himself in study, or faking it, thought Daniel.

He'd asked the juvenile officers to look into possible child abuse at home. Tried to find out who was protecting Malkovsky and had met with official silence.

Time to call Laufer for the tenth time.

Men of God.

He arrived home at six-thirty, ready for a family dinner, but found that they'd all eater*-felafel and American-style hamburgers picked up at a food stand on King George.

Dayan barked a greeting and the boys jumped on him. He kissed their soft cheeks, promised to be with them in a minute. Instead of persisting, they ran off cuffing each other. Shoshi was doing her homework at the dining room table. She smiled at him, hugged and kissed him, then returned to her assignment, a page of algebra equations-she'd completed half.

"How's it going?" Daniel asked. Math was her worst subject. Usually he had to help her.

"Fine, Abba." She bit her pencil and screwed up her face. Thought a while and put down an answer. The correct one.

"Excellent, Shosh. Where's Eema?"

"Painting." Absently.

"Have fun."

"Uh huh."

The door to the studio was closed. From under it seeped the smell of turpentine. He knocked, entered, saw Laura in a blue smock, working on a new canvas under a bright artist's lamp. A cityscape of Bethlehem in umbers, ochers, and beige, softly lit by a low winter sun, a lavender wash of hillside in the background.

"Beautiful."

"Oh, hi, Daniel." She remained on her stool, leaned over for a kiss. Half a dozen snapshots of Bethlehem were tacked to the easel. Pictures he'd taken during last year's Nature Conservancy hayride.

"You ate already," he said.

"Yes." She picked up the brush, laid in a line of shadow long the steeple of the Antonio Belloni church. "I didn't now if you were coming home."

He looked at his watch. "Six thirty-six. I thought it would be early enough."

She put the brush down, wiped her hands on a rag, and turned to him. "I had no way of knowing, Daniel."

she said in a level tone of voice. "I'm sorry. There's an extra hamburger in the fridge. Do you want me to heat it up for you?"

"It's all right. I'll heat it up myself."

"Thanks. I'm right in the middle of this-want to finish a fer more buildings before quitting."

"Beautiful," he repeated.

"It's for Gene and Luanne. A going-away present."

"How are they doing?"

"Fine." Dab, blend, wipe. "They're up in Haifa, touring the northern coast. Nahariya, Acre, Rosh Hanikra."

"When are they coming back down?"

"Few days-I'm really not sure." 'Are: they having a good time?"

"Seem to be." She got off the stool. For a moment Daniel thought she was going to embrace him. But instead she stepped back from the canvas, measured perspective, re-turned to her seat, and began blocking in ocher rectan-gles.

He waited a few seconds, then left to make himself dinner. By the time he'd eaten and cleaned up, the boys had busied themselves again with the Stars Wars videotape. Eyes filled with wonderment, they declined his offer to wrestle.

Stacks of newspaper clippings covered Laufer's desk. The deputy commander began fanning them out like oversized playing cards.

"Garbage-sifting time," he said. "Read."

Daniel picked up a clipping, put it down immediately after realizing it was one he'd already seen. Ha'aretz was his paper; he liked the independence, the sober tone-and the reporting on the murders was typical: factual, concise, no thrill for ghouls.

The party-affiliated papers were another story. The government organ gave the crimes short shrift on a back page, an almost casual downplay, as if hiding the story would make it go away.

The opposition paper played a shrill counterpoint, using Daniel's name to segue into the Lippmann case, offering a blow-by-blow rehash of the scandal, making much of the fact that prior to his assassination the late, discredited warden had been a darling of the ruling party. Implying, not so subtly, that any rise in violent crime was the government's fault: Failure to raise police salaries had led to continued corruption and ineptitude; a poorly administered Health Ministry had failed to handle the issue of dangerous mental patients; the psychological frustration caused by the ruling party's economic and social policies engendered "deep-rooted alienation and concomitant hostile impulses in the general populace. Impulses that are at risk for spilling over into bloodshed."

The usual partisan nonsense. Daniel wondered if anyone took it seriously.

Haolam Hazeh and the other tabloids had done their heavy-breathing bit: lurid headlines and hints of perverted sex in high places. Gory-detail crime stories fighting for space with photos of naked women. Daniel put them down on the desk.

"Why the rehash? It's been two weeks since Juliet."

"Go on, go on, you're not through," Laufer said, drum-ming his fingers on the desk. He picked up a thick batch of clippings and shoved it at Daniel.

These excerpts were all in Arabic: Al Fajr, Al Sha'ab, other locals at the top of the pile, foreign stuff on the bottom.

Arabic, thought Daniel, was an expansive, poetic lan-guage. lending itself to hyperbole, and this morning the

Arab journalists had been in fine hyperbolic form: Fatma and Juliet restored to virginity and transformed to political martyrs victimized by a racist conspiracy-abducted, defiled, and executed by some night-stalking Zionist cabal.

The local publications called for "hardening of resolve"

and "continuation of the struggle, so that our sisters have not perished in vain," stopping just short of a call for re-venge-saying it outright could have brought down the heavy hand of security censorship.

But the foreign Arab press screamed it out: officially sactioned editorials from Amman, Damascus, Riyadh, the Gulf stlates, brimming with hate and lusting for vengeance, accompanied by crude cartoons featuring the usual anti-Jewish archetypes-stars of David dripping blood; hooknosed, slavering men wearing kipot and side curls, pressing long-bladed knives to the throats of veiled, doe-eyed beau-ties wrapped in the PLO flag. The kipot emblazoned with swastikas-the Arabs loved to co-opt the Nazi stuff, spit it back at their cousins. The Syrians went so far as to link the murders to some occult Jewish ritual of human sacrifice-a harvest ceremony that the writer had invented.

Vile stuff, thought Daniel, reminiscent of the DerSt?rmer exhibit he'd seen at the Holocaust Memorial, the Black Book Ben David had shown him. But not unusual.

"The typical madness," he told Laufer.

"Pure shit. This is what stirred it up."

He gave Daniel an article in English, a cutting from his morning's international Herald Tribune.

It was a two-column wire service piece bearing no byline and entitled "Is a New Jack the Ripper Stalking the Streets of Jerusalem?" Subtitle: "Brutal Slayings Stymie Israeli Police. Political Motives Suggested."

The anonymous journalist had given the killer a name– the Butcher-an American practice that Daniel had heard Gene decry ("Gives the bad guy the attention he craves, Danny Boy, and makes him larger than life, which scares the heck out of the civilians. Every day that goes by without a bust makes us look more and more like clods"). The actual information about the killings was sparse but suggestively spooky and followed by a review of the Gray Man case, using copious quotes from "sources who spoke on condition they would not be identified" to suggest that both serial killers were likely to remain at large because Israeli police officers were inept homicide investigators, poorly paid, and occupying "lowly status in a society where intellectual and military accomplishments are valued but domestic service is demeaned." Illustrating that with a rehash of the six-month-old story about new recruits having to apply for welfare, the wives' picket of the Knesset.

The Herald Tribune article went on to wallow in armchair sociology, pondering whether the murders were symptomatic of "a deeper malaise within Israeli society, a collective loss of innocence that marks the end of the old idealistic Zionist order." Quotes from political extremists were given equal weight with those from reasoned scholars, the end result a weird stew of statistics, speculation, and the regurgitated accusations of the Arab press. All of it delivered in a morose, contemplative tone that made it sound reasonable.