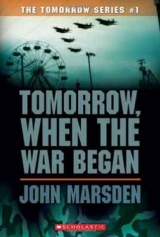

Текст книги "Tomorrow, When the War Began"

Автор книги: John Marsden

Соавторы: John Marsden

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Chapter Sixteen

There were two other documents in the box.

One was a letter from Imogen Christie’s mother. She wrote:

Dear Mr Christie, (‘“Mr Christie!”’ Lee commented; and I said, ‘Well, they were very formal in those days.’) I am in receipt of your letter of November 12. Indeed your position is a difficult one. As you know I have always stood by you and defended your account of the dreadful deaths of my dear daughter and my dear grandson, as being the only possible true one, and I have always believed and devoutly prayed it so to be. And I rejoiced, as you know, when the jury pronounced you innocent, for I believe you to have been a man unjustly accused, and if the Law does not know a case such as yours then more shame on the law I say, but the jury did the only thing possible, despite what the Judge said. And you know I have always held to the one point of view and have said so from one end of the district to the other. I cannot think that I could have done any more. No man, and no woman either, can still wagging tongues, and if they are as bad as you say and you will be forced to leave the district it is a shame but there is no stopping women once they begin to gossip, and I say it although I am a traitor to my sex, but there it is, that is the way of the world and no doubt always will be. And you know you will always be welcome under the roof of,

Imogen Emma Eakin

The last thing was a poem, a simple poem:

In this life of froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone.

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.

When we’d read that, Lee silently wrapped everything up again and replaced it in the tin. It didn’t surprise me when he put the tin back in the cavity and dropped the windowsill on top of it. I knew that we weren’t necessarily leaving it there forever, to decay into fragments and then dust, but at the moment there was too much to absorb, too much to think about. We left the hut silently, and we left it to its silence.

Half way back along the creek I turned to face Lee, who was splashing along behind me. It was about the only spot in the cool tunnel of green where we could stand. I put my hands around the back of his neck and kissed him hungrily. After a moment of shock, when his lips felt numb, he began kissing me back, pressing his mouth hard into mine. There we were, standing in the cold stream, exchanging hot kisses. I explored not just his lips but his smell, the feeling of his skin, the shape of his shoulder blades, the warmth of the back of his neck. After a while I broke off and laid my head against his shoulder, one arm still around him. I looked down at the cool steady-flowing water, moving along its ordained course.

‘That coroner’s report,’ I said to Lee.

‘Yes?’

‘We were talking about reason and emotion.’

‘Yes?’

‘Have you ever known emotion dealt with so coldly as in that report?’

‘No, I don’t think I have.’

I turned more, so that I could nuzzle into his chest, and I whispered, ‘I don’t want to end up like a coroner’s report.’

‘No.’ He stroked my hair, then felt up under it and squeezed the back of my neck softly, like a massage. After a few minutes more he said, ‘Let’s get out of this creek. I’m freezing by slow degrees. It’s up to my knees and rising.’

I giggled. ‘Let’s go quickly then. I wouldn’t like it to get any higher.’

Back in the clearing it was obvious that something had happened between Homer and Fi. Homer was sitting against a tree with Fi curled up against him. Homer was looking out across the clearing to where one of Satan’s Steps loomed high in the distance. They weren’t talking and when we arrived they got up and wandered over, Homer a little self-consciously, Fi quite naturally. But as I watched them a little during the rest of the afternoon – not spying, just with curiosity to see what they were like – I felt that they were different to us. They seemed more nervous with each other, a bit like twelve-year-olds on their first date.

Fi explained it to me when we managed to sneak off on our own for a quick goss.

‘He’s so down on himself,’ she complained. ‘Everything I say about him he brushes off or puts himself down. Do you know,’ she looked at me with her big innocent eyes, ‘he’s got some weird thing about my parents being solicitors, and living in that stupid big house. He always used to joke about it, especially when we went there the other night, but I don’t think it’s really a joke to him at all.’

‘Oh Fi! How long did it take you to work that out?’

‘Why? Has he said something to you?’ She instantly became terribly worried, in her typical Fi way. I was a bit caught, because I wanted to protect Homer and I didn’t want to break any confidences. So I tried to give a few hints.

‘Well, your lifestyle’s a lot different to his. And you know the kind of blokes he’s always knocked around with at school. They’d be more at home hanging out at the milk bar than playing croquet with your parents.’

‘My parents do not play croquet.’

‘No, but you know what I mean.’

‘Oh, I don’t know what to do. He seems scared to say anything in case I laugh at him or look down my nose at him. As if I ever would. It seems so funny that he’s like that with me when he’s so confident with everyone else.’

I sighed. ‘If I could understand Homer I’d understand all guys.’

It was getting dark and we had to start organising for a big night, starting with another hike up Satan’s Steps. I was tired and not very keen to go, especially as Lee wouldn’t be able to come. His leg was still stiff and sore. When the time came I trudged off behind Homer and Fi, too weak to complain – I thought I’d feel guilty if I did. But gradually the sweetness of the night air revived me. I began to breathe it in more deeply, and to notice the silent mountains standing gravely around. The place was beautiful, I was with my friends and they were good people, we were coping OK with tough circumstances. There were a lot of things to be unhappy about, but somehow the papers I’d read in the Hermit’s hut, and the long beautiful kiss with Lee, had given me a better perspective on life. I knew it wouldn’t last, but I tried to enjoy it while it did.

At the Landie we set about constructing a new hideaway for the vehicles, so that they’d be better concealed from anyone using the track. It wasn’t easy to do, and in the end we had to be content with a spot behind some trees, nearly a k further down the hill. Its big advantage was that to drive in there you had to go over rocks, which meant no tracks would be left, as long as the tyres were dry. Its big disadvantage was that it gave us a longer walk to get into Hell, and it was a long enough walk already.

Fi and Homer were going to wait up there for the other four, whom we were expecting back from Wirrawee at about dawn, but I didn’t want to leave Lee at the campsite on his own for the night. So, for that charitable reason, and no other, I filled a backpack to the brim, took a bag of clothes in my hand and, laden like a truck, put myself into four-wheel drive and trekked back into Hell on my own. It was about midnight when I left Fi and Homer. They said they were going to stretch out in the back of the Landrover for a few hours’ sleep while they waited.

That’s what they said they were going to do, anyway.

The moon was well up by the time I left. The rocks stood out quite brightly along the thin ridge of Tailor’s Stitch. A small bird suddenly flew out of a low tree ahead of me, with a yowling cry and a clatter of wings. Bushes formed shapes like goblins and demons waiting to pounce. The path straggled between them: if a tailor had stitched it he must have been mad or possessed or both. White dead wood gleamed like bones ahead of me, and my feet scrunched the little stones and the gravel. Perhaps I should have been frightened, walking there alone in the dark. But I wasn’t, I couldn’t be. The cool night breeze kissed my face all over, all the time, and the smell of the wattle gave a faint sweetness to the air. This was my country; I felt like I had grown from its soil like the silent trees around me, like the springy, tiny-leafed plants that lined the track. I wanted to get back to Lee, to see his serious face again, and those brown eyes that charmed me when they were laughing and held me by the heart when they were grave. But I also wanted to stay here forever. If I stayed much longer I felt that I could become part of the landscape myself, a dark, twisted, fragrant tree.

I was walking very slowly, wanting to get to Lee but not too quickly. I was hardly conscious of the weight of the supplies I was carrying. I was remembering how a long time ago – it seemed like years – I’d been thinking about this place, Hell, and how only humans could have given it such a name. Only humans knew about Hell; they were the experts on it. I remembered wondering if humans were Hell. The Hermit for instance; whatever had happened that terrible Christmas Eve, whether he’d committed an act of great love, or an act of great evil ... But that was the whole problem, that as a human being he could have done either and he could have done both. Other creatures didn’t have this problem. They just did what they did. I didn’t know if the Hermit was a saint or a devil, but once he’d fired those two shots it seemed that he and the people round him had sent him into Hell. They sent him there and he sent himself there. He didn’t have to trek all the way across to these mountains into this wild basin of heat and rock and bush. He carried Hell with him, as we all did, like a little load on our backs that we hardly noticed most of the time, or like a huge great hump of suffering that bent us over with its weight.

I too had blood on my hands, like the Hermit, and just as I couldn’t tell whether his actions were good or bad, so too I couldn’t tell what mine were. Had I killed out of love of my friends, as part of a noble crusade to rescue friends and family and keep our land free? Or had I killed because I valued my life above that of others? Would it be OK for me to kill a dozen others to keep myself alive? A hundred? A thousand? At what point did I condemn myself to Hell, if I hadn’t already done so? The Bible just said ‘Thou shalt not kill’, then told hundreds of stories of people killing each other and becoming heroes, like David with Goliath. That didn’t help me much.

I didn’t feel like a criminal, but I didn’t feel like a hero either.

I was sitting on a rock on top of Mt Martin thinking about all this. The moon was so bright I could see forever. Trees and boulders and even the summits of other mountains cast giant black shadows across the ranges. But nothing could be seen of the tiny humans who crawled like bugs over the landscape, committing their monstrous and beautiful acts. I could only see my own shadow, thrown across the rock by the moon behind me. People, shadows, good, bad, Heaven, Hell: all of these were names, labels, that was all. Humans had created these opposites: Nature recognised no opposites. Even life and death weren’t opposites in Nature: one was merely an extension of the other.

All I could think of to do was to trust to instinct. That was all I had really. Human laws, moral laws, religious laws, they seemed artificial and basic, almost childlike. I had a sense within me – often not much more than a striving – to find the right thing to do, and I had to have faith in that sense. Call it anything – instinct, conscience, imagination – but what it felt like was a constant testing of everything I did against some kind of boundaries within me; checking, checking, all the time. Perhaps war criminals and mass murderers did the same checking against the same boundaries and got the encouragement they needed to keep going down the path they had taken. How then could I know that I was different?

I got up and walked around slowly, around the top of Mt Martin. This was really hurting my head but I had to stay with it. I felt I was close to it, that if I kept my grip on it, didn’t let go, I might just get it out, drag it out of my begrudging brain. And yes, I could think of one way in which I was different. It was confidence. The people I knew who thought brutal thoughts and acted in brutal ways – the racists, the sexists, the bigots – never seemed to doubt themselves. They were always so sure that they were right. Mrs Olsen, at school, who gave out more detentions than the rest of the staff put together and kept complaining about ‘standards’ in the school and the ‘lack of discipline’ among ‘these kids’; Mr Rodd, down the road from us, who could never keep a worker for more than six weeks – he’d gone through fourteen in two years – because they were all ‘lazy’ or ‘stupid’ or ‘insolent’; Mr and Mrs Nelson, who drove their son five kilometres from home every time he did something wrong and dropped him off and made him walk home again, then chucked him out for good when he was seventeen and they found the syringes in his bedroom – these were the ones I thought of as the ugly people. And they did seem to have the one thing in common – a perfect belief that they were right and the others wrong. I almost envied them the strength of their beliefs. It must have made life so much easier for them.

Perhaps my lack of confidence, my tortuous habit of questioning and doubting everything I said or did, was a gift, a good gift, something that made life painful in the short run but in the long run might lead to ... what? The meaning of life?

At least it might give me some chance of working out what I should or shouldn’t do.

All this thinking had tired me out more than the work hiking up and down the mountains. The moon was shining brighter than ever but I couldn’t stay. I got up and went down the rocks to the gum tree and the start of the trail. When I got back to the campsite I was disgusted to find Lee sound asleep. I could hardly blame him, considering how late it was, but I’d been looking forward all evening to seeing him and talking to him again. After all, it had been his fault that I’d been going through this mental sweat-session. He’d started it, with his talk about my head and my heart. Now I had to console myself with crawling into his tent and sleeping next to him. The only consolation was that he would wake in the morning and find he had slept with me and not even known it. I think I was still smiling about that when I fell asleep.

Chapter Seventeen

Robyn and Kevin and Corrie and Chris were beaming. It wasn’t hard to beam back. It was such a relief, such a joy, to see them again. I hugged them desperately, only then aware how frightened I’d been for them. But for once everything seemed to have gone well. It was wonderful.

They hadn’t told Homer and Fi much, because they were tired, and because they didn’t want to repeat themselves when they reached Lee and me. All they’d said was that they hadn’t seen any of our families, but they’d been told they were safe and at the Showground. When I heard this, it was such a relief that I sat down quickly on the ground, as though I’d had the breath knocked out of me. Lee leant against a tree with his hands over his face. I don’t think anything else mattered to us much. We did have lots of questions, but we could see how exhausted everyone was, so we were content to let them have their breakfasts before they told us any more. And with a good breakfast in them – even a few fresh eggs, cooked quickly and dangerously on a small fire, which we put out just as quickly – they settled down, full of food and adrenalin, to tell us the lot. Robyn did most of the talking. She’d already been their unofficial leader when they left, and it was interesting to see how much she was running the show now. Lee and I sat on a log holding hands, Fi sat against Homer in the V formed by his open legs, and Kevin lay on the ground with his head in Corrie’s lap. It was like Perfect Partners, and although I still wondered if I might have liked to swap places with Fi, I was happy enough. It was just too bad that there was no chance of Chris and Robyn getting off together, then we really could have had Perfect Partners.

Chris had brought back a few packets of smokes and two bottles of port that he’d ‘souvenired’, as he called it. He sat on the log beside me, until he lit up and I politely asked him to move. I couldn’t help wondering how far we could go with this ‘souveniring’ idea. It made me reflect on what I’d been thinking about the night before. If we were going to ignore the laws of the land, we had to work out our own standards instead. I had no problem with all the laws we’d broken already – so far we could have been charged with stealing, driving without a licence, wilful damage, assault, manslaughter, or murder maybe, going through a stop sign, driving without lights, breaking and entering, and I don’t know how many other things. It seemed like we’d be committing under-age drinking soon too, not for the first time in my life, I have to admit. That didn’t bother me either – I’d always thought the law on that was typical of the stupidity of most laws. I mean, the idea that at seventeen years, eleven months and twenty-nine days you were too immature to touch alcohol but a day later you could get wasted on a couple of slabs wasn’t exactly bright. But I still didn’t like the idea of Chris picking up grog and cigarettes whenever and wherever he felt like it. I suppose it was because they weren’t as essential as the other things we’d knocked off. Admittedly I’d taken some chocolate from the Grubers’, which wasn’t much different, except that at Outward Bound they’d given us chocolate for energy, so there was at least something good you could say about chocolate. There wasn’t an awful lot you could say for port or nicotine.

I wondered what would happen if Chris brought anything stronger into Hell, or if he tried to grow dope or something down here. But meanwhile Robyn was starting on the big speech, so I stopped thinking about morality and started concentrating on her.

‘OK boys and girls,’ she began. ‘Everyone ready for story time? We’ve had a pretty interesting couple of days. Although,’ she added, looking at Lee and me, and Homer and Fi, ‘you guys seem to have had an interesting couple of days yourselves. It mightn’t be safe to leave you here alone again.’

‘OK Mum, get on with it,’ Homer said.

‘All right, but I’m watching you, remember. Well. Where do I start? The first thing, as we’ve said already, is that we haven’t seen any of our families, but we’ve heard about them. The people we talked to swear they’re all OK. In fact everyone in the Showground is meant to be in good nick. What we said jokingly a while back is quite true: they have got plenty of food. They’ve eaten the scones, the decorated cakes, the sponges, the home-made bread, the matched eggs, the novelty cakes ... Have I left anything out?’

‘The fruit cakes,’ said Corrie, who was an expert on these subjects. ‘The jams, preserves and pickles. The Best Assorted Biscuits.’

‘OK, OK.’ About three people spoke at once.

‘And,’ said Robyn, ‘they’re eating their way through the livestock. It’s a shame really, because it’s some of the best stock in the district. So they should be getting some top quality tucker. They bake bread in the CWA tearooms every morning – there’s a couple of stoves in there. For a while they were running short of greens, once they’d eaten the Young Farmers’ display, which I might add I helped set up, the day before we went on our hike.’

‘You’re not a Young Farmer,’ I said.

‘No, but Adam is,’ she said, looking faintly embarrassed.

When our immature wolf whistles and animal noises had died down, she continued, undaunted.

‘But there’s been a few developments,’ she said. ‘They’ve now got work parties going out of the Showground each day. They go in groups of eight or ten, with three or four guards. They do jobs like cleaning the streets, burying people, getting food – including the greens – and helping in the Hospital.’

‘So the Hospital is running? We thought it was.’

‘Yes. Ellie’s been keeping it busy.’

As soon as she said that, she looked like she wished she hadn’t.

‘What? Did you hear something?’

She shook her head. ‘No, no, nothing.’

‘Oh come on, don’t do that Robyn. What did you hear?’

‘It’s nothing Ellie. There were some casualties. You know that.’

‘So what did you hear?’

Robyn looked uncomfortable. I knew I’d be sorry but I’d gone too far to stop. ‘Robyn! Stop treating me like a kid! Just tell me!’

She grimaced but told me. ‘Those three soldiers hit by the ride-on mower, two of them died, they think. And two of the people we ran over.’

‘Oh,’ I said. She’d said it flatly and calmly, but the shock was still terrible. Sweat broke out on my face and I felt quite giddy. Lee gripped my hand hard, but I hardly felt it. Corrie came and sat on my other side, where Chris had been, and held me.

After a minute Chris said, ‘It’s different from the movies, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I’m OK. Please, just go on Robyn.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘I’m sure.’

‘Well, the Hospital’s had a few other casualties. The first day or two there was a lot of fighting, and a lot of people got hurt or killed. Soldiers and civilians. Not at the Showground – the surprise was so complete that they took the whole place in ten minutes – but in town and around the district, with people who hadn’t gone to the Show. And it’s still going on – there’s a few groups of guerillas, just ordinary people like us I guess, who are hanging around and attacking patrols when they get a chance. But the town itself is quiet. They seem to have flushed everyone out, and they’re confident that they’ve got it under control.’

‘Are they treating people well?’

‘Mostly. For example, the people who were in hospital the day of the invasion have been kept there, and looked after. The people we’ve talked to say the soldiers are anxious to keep their noses clean. They know that sooner or later the United Nations and the Red Cross’ll be wandering around, and they don’t want to attract a lot of heat from them. They keep talking about a “clean” invasion. They figure that if there’s no talk of concentration camps and torture and rape and stuff, there’s less chance of countries like America getting involved.’

‘That’s pretty smart,’ Homer said.

‘Yes. But for all that, there’s been about forty deaths just around Wirrawee alone. Mr Althaus, for one. The whole Francis family. Mr Underhill. Mrs Nasser. John Leung. And some people have been bashed for not obeying orders.’

There was a shocked silence. Mr Underhill was the only one of those I knew well. He was the jeweller in town. He was such a mild man that I couldn’t imagine how he might have aggravated the soldiers. Perhaps he’d tried to stop them looting his store.

‘So who have you been talking to?’ Lee asked at last.

‘Oh yes, I was getting to that. I’m telling this all out of order. OK, so this is what happened. We cruised into town the first night, no problems. We got to my music teacher’s house about 1.30 am. The key was where she always left it. It is a good place to hide out, like I said, because there’s so many doors and windows you can get out of. There’s a good escape route out of an upstairs window, for example, where you can go across the roof, onto a big branch, and be next door in a couple of seconds. Also, the sentry has a great view of the street and the front drive, and there’s no way anyone could get over the back fence without a tank. So that was cool. The first thing we did after we sussed out the house was to get some gear together and go and set up the fake camp under the Masonic Hall. That was quite fun – we put in a few magazines and photos and teddy bears to make it look authentic. Then Kevin took the first sentry duty and the rest of us went to bed.

‘At about eleven in the morning I was on sentry duty and suddenly I saw some people in the street. There was a soldier and two of our people. One of them was Mr Keogh, who used to work at the Post Office.’

‘You mean the old guy with no hair?’

‘Yes. He retired last year I think. Well, I woke the others fast, as you can imagine, and we watched them working their way along the street. There were three soldiers altogether, and six people from town. They had a ute and a truck, and it seemed like they were clearing stuff out of each house. Two of them would go into a house while the soldiers lounged around outside. The people spent about ten minutes in each house, then they’d come out with green garbage bags full of stuff. They’d chuck some bags straight into the truck, but other bags were checked by the soldiers and put in the ute.

‘So what we did was, when they got close to us we hid in different parts of the house and waited for them. I was in the kitchen, in a broom cupboard. I’d been there about twenty minutes when Mr Keogh came in. He opened the fridge door and starting clearing out all this smelly, foul stuff. It was the job we hadn’t been able to bring ourselves to do on an empty stomach when we’d got there at 1.30.

‘“Mr Keogh!” I whispered. “This is Robyn Mathers.” You know, he didn’t even blink. I thought, this guy is cool. Then I remembered that he’s quite deaf. He hadn’t even heard me. So I opened the door of the broom cupboard and snuck up behind him and tapped his shoulder. Well! I know Chris said a few minutes ago that war’s not like the movies, but this sure was. He jumped like he’d touched a live wire in the fridge. I had to hold him down. I thought “Help, I hope he doesn’t have a heart attack”. But he calmed down. We talked pretty fast then. He had to keep working while we talked – he said if he took too long the soldiers would get suspicious and come in. He said his job was to make the houses habitable again, by cleaning out mouldy food, and dead pets, and to pick up valuables, like jewellery. He told me about our families, and all that other stuff. He said the work parties would be going out to the country too, starting any day now, to look after the stock and get the farms going again. He said they’re going to colonise the whole country with their own people, and all the farms will be split up between them, and we’ll just be allowed to do menial jobs, like cleaning lavatories I suppose. Then he had to go, but he told me they were doing West Street after Barrabool Avenue, and if I got into a house there we could talk some more. And off he went.

‘Well, when the house was empty again we had a quick conference. Kevin had talked to a lady called Mrs Lee, who’d come into the bedroom where he was hiding and he’d got more information from her. So we agreed to go to West Street and try again. We got there fairly easily, by going through people’s gardens, and we tried a few different houses. The first two were locked still but the third one was open, so we spread ourselves around it. I got under the bed in the main bedroom. Chris kept watch and told us when they were getting close, which wasn’t for nearly two hours. It was pretty boring. If you want to know how many cross-wires the people at 28 West Street have got on the underside of their bed, I can tell you. But finally someone came in. It was a lady I didn’t know, but she had a green bag and she went to the dressing table and started scooping stuff out. I whispered “Excuse me, my name’s Robyn Mathers”, and without looking round she whispered “Oh good, Mr Keogh told me to watch out for you young ones”. We talked for a few minutes, with me still under the bed, but sticking my head out. She said she hated having to do this work, but the soldiers occasionally checked a house after they came out, and they got punished if they’d left anything valuable behind. “Sometimes I’ll hide something in the room if it looks like a family heirloom,” she said, “but I don’t know if it’ll make any difference in the long run.” She also told me that they were picking the least dangerous people for the work parties – old people and kids mainly – and they knew that if they tried to escape or do anything wrong their families back at the Showgrounds would be punished. “So I don’t want to talk to you for long dearie,” she said. She was a nice old duck. The other thing she told me was that the highway from Cobbler’s Bay is the key to everything. That’s why they hit this district so hard and so early. They bring their supplies in to Cobbler’s by ship and send it down the highway by truck.’

‘Just like I said,’ I interjected. I’d never thought of myself as a military genius, but I was pleased to find I’d got this right.

Robyn went on. ‘Anyway there we were, chatting away like old mates. She even told me how she used to work as a cleaner at the chemist, part-time, and how many grandchildren she had, and their names. She seemed to have forgotten what she’d said about having a short conversation. Another couple of minutes and I think she would have taken me into the kitchen and made a cup of tea, but I suddenly realised there were these soft little footsteps coming along the hall I pulled my head back in like a turtle, but I tell you, I moved quicker than any turtle. And the next thing, there were these boots right next to the bed. Black boots, but very dirty and scuffed. It was a soldier, and he’d come sneaking along the corridor to try to catch her out. I thought “What am I going to do?” I tried to remember all the martial arts stuff that I’d ever heard of, but all I could think of was to go for the groin.’

‘That’s all she thinks of with any guy,’ Kevin said.

Robyn ignored him. ‘I was so scared, because I didn’t want to cause any trouble for this nice old lady. I didn’t even know her name. Still don’t. And I didn’t want to get myself killed either. I’m funny like that. But I was so paralysed I couldn’t move. I heard the guy say, very suspiciously, something like “You talking”. I knew I was in trouble then. I rolled across the floor to the other side of the bed and crawled out from under the bedspread. I was in this little gap between the bed and the wall, about a metre wide I guess. I heard the old lady laugh nervously and say “To myself. In the mirror.” It sounded weak to me and I guess it did to him too. All I had going for me was my hearing, and my guesses. I knew he was going to search the room and I guessed he’d start by lifting the bedspread and looking under the bed. Then he’d come round the base of the bed and either go to the built-in, or look in the little gap where I was lying. There were no other places in the room where anyone could hide. It was a bare room, not very nice at all. So I listened for the little swish of his lifting the bedspread, and sure enough the room was so quiet I heard it. In fact the room was so quiet I thought I could hear the old lady’s heart beating. I knew I could hear my own heart beating. I could hardly believe that the soldier couldn’t hear it. Anyway, the trouble was I couldn’t hear the second little swish that he should have made when he dropped the bedspread back down. I was in agony, wondering if he was still staring under the bed or if he was coming around to where I was lying. God, I was listening so hard I could feel my ears grow. I felt like I had two satellite dishes on the sides of my head.’