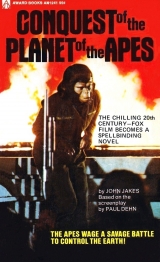

Текст книги "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes "

Автор книги: John Jakes

Жанры:

Альтернативная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

THE TIME: 1990

THE PLACE: A gray, tightly computerized city-state, somewhere in North America

THE INHABITANTS: Apes who serve as terrified slaves. Men who function as brutalized masters

Until the Apes revolt . . . in a battle as savage and monstrous as the bondage they’d been forced to endure for decades!

20th Century-Fox Presents

An Arthur P. Jacobs Production

CONQUEST OF THE PLANET

OF THE APES

Starring

RODDY McDOWALL and DON MURRAY

and

RICARDO MONTALBAN

as Armando

Produced by

APJAC PRODUCTIONS

Directed by

J. LEE THOMPSON

Written by

PAUL DEHN

Based on Characters from

PLANET OF THE APES

Music by

TOM SCOTT

CONQUEST OF THE PLANET OF THE APES

FIRST AWARD PRINTING February 1974

Copyright © 1972, 1974 by

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation.

All rights reserved

AWARD BOOKS are published by

Universal-Award House, Inc., a subsidiary of

Universal Publishing and Distributing Corporation,

235 East Forty-fifth Street, New York, N.Y. 10017

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

Title

Copyright

CONQUEST OF THE PLANET

OF THE APES

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

PROLOGUE

Under a red-tinged moon, the dark towers of the central city thrust against the sky. Black glass facades caught the moon’s reflection, sectioned it like so many endlessly repeated blank faces.

Aerial walkways arched gracefully between the cubistic towers, empty at this hour. From the buildings, and from intersections along the walkways, ramps led down to the perimeter of a vast mall, a checkerboard of small green pocket parks and paving blocks that reflected the moon from their mica flecks. There was no sound except the tack-tacking of the boots of a helmeted state security policeman walking along a parapet above the plaza. His rifle barrel glittered, slung over his shoulder, muzzle upward.

The policeman drew in a breath of the cool, fresh air. Two years ago, in 1989, the last of the huge air-scrubbing plants, constructed at a cost of billions along the mountain chain a hundred miles eastward, had, in combination with stringent laws, made it pleasant to breathe again—at least in this American city. The policeman couldn’t speak for others, never having traveled much.

But he’d heard it was the same in all the great metro sprawls. An ordered society. Law breakers—including polluters—were promptly, severely punished. And the masses of people had been relieved of menial chores by the careful conditioning of thousands of . . .

Abruptly, the policeman stiffened, cocked his head. His helmet flashed moon reflections. Somewhere deep in the glass and steel canyons surrounding the mall, he heard soft, urgent footfalls.

Then another sound made him glance quickly up and down the mall. The second noise was—a jungle sound.

He had seen pictures of the world’s few remaining jungle places on solido shows. The policeman reached up, slowly unslung his rifle. He was sure now. What he’d heard was the whimpering cry of a frightened animal—a running animal.

His face tense, the policeman headed for the nearest ramp. His boots clacked as he ran down to the mall proper. He searched one direction, then another. Nothing but shadows, glass, silence. The footfalls had stopped.

But in thicker shadow beneath another ramp angling down to the pavement far on his right, he swore he heard the light, raspy sound of something breathing.

He whipped around as a shadowy figure broke from under the ramp. The figure began to zigzag between the pocket parks in an unmistakable shambling stride.

Almost before he realized it, the policeman was running himself. He understood the nature of the humped silhouette; understood why it scurried so rapidly across the plaza, dashing past building entrances, temporarily vanishing behind ramp pillars, then plunging frantically on again.

High on another parapet to his left, he heard a word barked by a human voice, then realized it was his own name, called out by a colleague who patrolled blocks Q four through seven. Moving fast, trying to keep the fleeing figure in sight, the first policeman shouted up to the other: “Runaway!”

The cause of the flight, or the identity of the fugitive, he did not know. But he knew that what was happening violated their conditioning, and therefore could not go unchecked. He breathed hard, gripping the rifle in a sweaty palm as he ran. Finally the fleeing figure broke into plain sight, forced to cross a wide paved area in order to reach the sanctuary of the streets opening from the mall’s far side.

The state security policeman halted, braced his booted feet, brought the rifle halfway to his shoulder. He yelled the command that carried more power—with them—than lethal weapons:

“No!”

The echo bounced off the high buildings. And, for a moment, the fleeing figure did react, break stride—almost hesitate. But ultimately, the traditional command failed to work. The figure went shambling on, the emptiness flinging back the whimpering, terrified sound it made.

“Jesus Christ,” said the policeman with a violent swallow. “A real renegade.”

His training had the rifle at his shoulder by then. With only an instant’s pause, he squeezed the trigger. The first thunderous report was followed by a second.

The distant figure spun, toppled to the paving stones, flat on its back, arms flung wide. It let out a piercing bellow of animal agony. The policeman had never shot one of them before. There was a shock reaction as he dashed forward, sourness rising in his throat. Coming down the ramp from above, the boots of his colleague slammed like ghostly echoes of the shots.

The policeman knew what he would find—an ape. He discovered it was a large, mature, male chimpanzee. It wore only green trousers now, the rest of its servant’s garb cast off somewhere as part of its desperate flight to freedom. What the policeman and his companion had not expected to see was the condition of the chimpanzee’s face and hairy upper body.

Welts—open wounds—glistened in the moon’s orange light.

“God, his master must have beat the hell out of him,” breathed the second policeman, peering at the fallen simian with a grimace of distaste.

“Maybe that’s why he tried it,” said the first, wiping sweat from his upper lip. He’d just noticed something else. The ape’s eyes were not completely closed. Nor was his breathing completely stopped. The powerful chest continued to pump ever so slightly—and the chimpanzee stared at them with eyes momentarily bright with hatred.

Then a cry of pain ripped out between the ape’s lips. The eyes glazed, closed slowly. The chimpanzee was dead.

The first policeman didn’t move. His thin voice expressed his shock: “I yelled at him. You heard me—”

“I heard you.”

“Didn’t do a damn thing. Slowed him maybe a second, no more.”

“A lousy conditioning job,” said the other, trying for a callous shrug.

“I wonder how many other lousy conditioning jobs are wandering around this city grinning and lighting cigarettes and cleaning toilets.” The first policeman glanced uneasily at the moon splinters on the towers. “I hope to God not many. If enough of them hated us the way that big bastard hated us when he was dying—” He let the rest trail off, too unpleasant to contemplate.

His colleague’s laugh sounded forced. “What’s with the God bit? It’s the government that keeps ’em from running wild.”

“But did you see the way he stared at us? I just think that if a couple of hundred of those bull apes ever went really wild, this city’d need a hell of a lot more than the government to protect it. I hope I’m not on duty if it happens.”

“You will be,” grumbled the other. “You are the government, my friend.”

The two stared at each other in glum silence. From far away down one of the dark boulevards came the shrilling sound of another one of them crying out.

In pain—or fury.

ONE

The passenger helicopter swept down across the glass-faced cubes of the city in the bright morning sunshine. Rotors whipping out wind and noise, it descended to the heliport pad atop one of the largest high rises near the city core. When the hatch opened, a file of suntanned commuters from the northern valley descended one by one. But the last two out of the ’copter were hardly typical commuters.

The man came first—heavy-set, florid, with gray in his wavy hair, and a maroon suit whose rather bold, showy cut instantly said that he was no conservative toiler in a futures’ exchange or ad-sell shop. He dressed like someone connected with the entertainment industry. Still, the cuffs and elbows of his jacket revealed wear. He was, then, in some less lucrative sector of the business.

The man had a stout leash looped around his right wrist. And it was his companion, at the other end of the leash, who continued to produce over-the-shoulder stares of curiosity from the commuters lining up at the rooftop check-in point.

At the end of the leash was a young but full-grown chimpanzee; a magnificent specimen, with alert eyes. The chimp blinked in the sunlight as he surveyed the panorama of towers and cubes ranged below the heliport on every side.

He was unusually dressed: a bright checked shirt; black breeches, black riding boots. In one hairy hand he carried a sheaf of colorful handbills.

The pair took places at the rear of the check-in line. Ahead, each passenger was having his or her identity card examined by two uniformed men from State Security. There was nothing perfunctory about the examination; each person’s card was scrutinized closely by the unsmiling officers. Finally, the heavy-set man and the leashed chimp reached the desk.

While one of the officers stared disapprovingly at the ape, the other accepted the card handed over by his master.

“Armando—is that a first or last name?”

With a shy smile and a bob of his head, the heavy-set man, answered, “Both, sir—that is, it’s my only name now. A professional name. Legally registered. I am the proprietor of a traveling entertainment. We are currently playing a two-week stand in the northern exurbs.”

The second officer jerked a thumb at the ape. “Do you have authorization to dress him like that?”

“Oh, yes, sir.” Armando fished an official-looking, stamped document from under his coat, and handed it across.

The second officer unfolded the document, scanned it, then returned it with another glance at the docile animal on the leash.

“A circus ape, huh?”

“That’s correct, sir,” said Armando, with obvious pride. “The only one ever to have been trained as a bareback rider in the entire history of the circus.”

“I thought circuses were definitely past history,” observed the first man.

With a smile, Armando plucked one of the handbills from the ape’s fingers. “Not while I live and breathe, gentlemen!”

Colorful type announced ARMANDO’S OLD-TIME CIRCUS. Smaller type below listed performance dates, times, and location. The handbill’s main illustration was a rather blurry photograph of the ape in the checked shirt. In the photo, he was standing on top of the bare back of a galloping white horse.

“Mind if I hang onto this?” the first officer asked. “My kid might get a kick out of an old-fashioned show like yours.”

“My pleasure, sir,” Armando said, still smiling his sleek, professional smile. “To promote attendance is precisely why we’ve come into the city with all these handbills.”

The officer tucked the flyer in his pocket, then passed the identity card back to its owner. “Okay, Señor Armando. Go ahead—and good luck.”

The officer pressed a button. A barrier gate slid aside. Armando gave a gentle tug on the leash.

“Come, Caesar.”

Armando started toward the elevator loading area, but doors were closing on the last carload of commuters. He paused, looked around, spotted an illuminated directional sign. Giving another tug on the leash, he led the ape toward the door to an interior staircase.

They’d gone down two flights, and reached a turning between floors, when Armando felt a tug from the other end of the leash. He turned to see the young ape looking at him alertly and with interest.

“Señor Armando,” the ape said distinctly, “did I do all right?”

Armando glanced uneasily down the stairwell, then smiled. “Yes. Just try to walk a little more like a primitive chimpanzee.” Relaxing the leash, he illustrated: “Your arms should move up and down from the shoulders—so! Without that, you look far too human.”

Vaguely puzzled for a moment, the ape nevertheless nodded. He slumped a little, imitating the circus owner’s movements. Armando was pleased.

“Much better.”

But there was a touch of sadness in the man’s eyes as he went on, “After twenty years in the circus, you’ve picked up evolved habits. From me, principally. Always remember—those must be disguised. They could be dangerous. Even fatal.”

“I know you keep telling me that, Señor Armando. But I still don’t really understand wh—”

Caesar broke off as Armando made a cautionary gesture. Two levels below, a woman and her daughter were coming up the stairs. Armando signaled Caesar to follow, darted down to the next landing and out through the door. In the bright corridor, another illuminated sign pointed the way to Aerial Cross-Ramp 10. They hurried that way, past closed office doors muting the sounds of voices and machines.

Once into the oval-windowed cross-ramp with the crowded plaza far below, Armando paused again. He risked speaking with quiet urgency.

“Caesar, listen to me most carefully. As I have reminded you before, there can be only one—one!—talking chimpanzee on all of earth: the child of the two other talking apes, Cornelius and Zira, who came to us years ago, out of the future. They were brutally murdered by men for fear that, one very distant day, the apes might dominate the human race. Men tried to kill you, too, and thought they had succeeded, but Zira took a newborn chimp from my circus and left you with its mother, hoping to save your life. I guarded you—even changed your name from the Milo they had given you—and raised you as a circus ape. But of course you inherited the ability to speak.”

The chimpanzee’s large, luminous eyes looked troubled. “But outside of you, Señor, no one knows I can speak.”

“And we must keep it that way. Because the fear remains. The mere fact of the existence of an ape with the capability to speak would be regarded as a great threat to mankind. That’s the way the world is today. When you realize how apes are treated—the roles they’ve come to occupy in society—”

The words trailed off. Armando stared glumly out one of the oval windows.

Caesar touched his arm. “Please finish what you were going to say.”

Armando turned back, said with obvious effort, “The comradeship of the circus, where humans are generally kind to animals, is very different from what you are about to see. That is why I’ve kept you away from all but our own people until I felt you were sufficiently mature. And I have kept your secret to myself, not willing even to trust our fellow performers with the staggering truth of—what you are.”

“But I don’t see what difference my speaking could—”

“Sssh!” Armando broke in. “From now on—no talking whatsoever!” For the benefit of a businessman approaching briskly, he tugged on the leash and said in an irritated voice, “Come, come!”

Pulled off balance, Caesar lurched clumsily forward. The businessman passed them with a curious stare. Caesar’s mind tumbled thoughts one on top of another.

What was so terrible about the populated cities that Armando had insisted on keeping him away from them until now? And why would the fact that he was able to organize his thoughts, articulate them aloud in Armando’s own language, endanger him? He’d heard it often before, but it still made no sense!

Caesar wished that Armando had not decided to bring him to the city at all, to try to generate business for the struggling little circus. All at once Caesar wanted to be back in the comfortable, familiar surroundings, traveling between the tiny outlying towns in the circus vans; performing his horseback tricks under the lights, warmed by the applause. In the circus, the names Cornelius and Zira were only mysterious tokens of his past; the names of a father and mother he had never seen. Here, as he scuttled obediently behind the striding Armando, the names assumed new dimensions; what he had inherited from Cornelius and Zira somehow threatened him.

And so he must conceal that inheritance. Keep silent. For the first time that he could remember, the constraint of Armando’s leash—employed only in public—angered him.

“Moving stair,” Armando warned, stepping onto a down escalator at the end of the ramp. “Mind your balance—”

Caesar needed little more cautioning than that. He kept his eyes glued to his feet as the stair carried them downward. Armando was one step below, his dark eyes still unhappy. Finally he swung his head around, gave the young chimpanzee a look of deep sympathy.

“When we reach the bottom—the first of the shopping areas we will visit today—prepare yourself for a shock. And above all—do not speak.”

Crowd noise, the bustle of a thronged plaza, drifted up from the bottom of the escalator. Caesar stumbled when the stair deposited them on the main level. Armando clutched him to keep him from falling, noting with new dismay the shock and astonishment that filled Caesar’s eyes in response to what he saw before him.

TWO

Though it was only a few minutes past ten in the morning, the plaza was already crowded with human beings, and with apes. Apparently vehicular traffic was barred from the central city. A few moments of scrutiny revealed other, more upsetting distinctions to Caesar.

The groups, human and ape, did not intermingle. The humans, a mixture of whites, black, and orientals, seemed to move at a leisurely pace, chatting with animation, virtually ignoring the chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans shuffling in and out among them. Only here and there did Caesar notice a quick-darting human glance settle on one of the apes, as if the man or woman were watching for some sign of trouble.

Caesar immediately decided that the smiles on the human faces looked forced, as if the apparent casualness of the people hid some inner tension. Why should that be so when the plaza, a place of sparkling miniature parks, shooting fountains, shop windows colorfully lit to highlight the endless displays of consumer goods, appeared so peaceful and prosperous?

He noted glances being cast his way—and a servile smile on Armando’s face as they drifted through the crowd, Armando handing out flyers. Caesar took the cue, offering handbills to some of the humans. They accepted them warily, as if concerned about coming too close. What were they afraid of? He had no clear notion.

A few more minutes of wandering through the crowds sharpened Caesar’s awareness of another distinction. The humans’ clothes, though expensively cut, were austere, generally monochromatic. But the costumes of the apes were variegated. Observation revealed that gorillas wore red, orangutans a rich tan, and chimpanzees like himself were garbed in green. There was also a distinct and consistent style for each sex. The females were clad in long-sleeved, full-length robes; the males in trousers and tight-fitting, high-collared coats. Occasionally an adult ape would stare briefly at Caesar, and—unless he was imagining it—react with a twitch of the nostrils or a blink of the eyes. Caesar tended to stop and gawk back. Armando’s tugs on the leash—“Come!”—occurred more frequently.

Caesar realized he was attracting undue attention with his staring. He tried to keep pace with his master, passing out the handbills while still absorbing as much information about his surroundings as he could.

He sorted out the sights and sounds, rearranged them in another, emerging pattern: the humans, while moving with some apparent purpose, did not seem to be engaged in any kind of physical labor. This was the function of the apes! The realization impacted his mind with stunning force. The moment it flashed through his mind, he saw it validated on every hand.

He noted a large, handsome female orangutan carrying a hamper of clothing. Then, on the far side of the plaza, a group of male gorillas in a line, sweeping the paving blocks with brooms. A pert female chimp with bright eyes gave Caesar an interested glance as she went by, carrying over her arm several women’s dresses wrapped in glistening plastic.

So the humans and the apes did not intermingle, exccpt in an isolated case or two, where an ape seemed to be trailing the heels of a human master or mistress. And the apes served the humans . . .

Those two realizations were enough to jam Caesar’s mind with new, disturbing implications. But the shocking learning process of which Armando had warned him was only beginning.

After another twenty minutes of distributing the handbills, Caesar grew aware of a deception. The docility of the servants was a veneer.

He saw an ape glare at a nearby human on more than one occasion. Then Señor Armando’s route led them near the squad of broom-wielders. Caesar heard an occasional resentful grunt. One or two gorillas seemed to wear sullen looks.

The closer Caesar looked, the more apparent became this subsurface resentment. No wonder the humans shied from physical contact with Caesar’s outstretched hand, or carefully chose their paths through the crowd to avoid bumping into their inferiors.

On some ape faces, Caesar recognized outright fear. It registered most strongly among the females. He watched a soft-eyed girl chimp, a market basket laden with brightly wrapped food packages in each hand, cast a nervous glance toward helmeted police officers patrolling the plaza in pairs. Once Caesar looked for these figures of authority, he was amazed at their number. All were armed with thick truncheons, or gleaming metallic rods whose function he did not understand . . .

Until one of the gorillas flung down his broom and simply stood, snuffing and swinging his massive head from side to side.

Two policemen strode forward. One jabbed his metallic rod against the gorilla’s back. The gorilla stiffened, roared. Obviously he had received some sort of strong shock.

The gorilla glowered at the policemen standing shoulder to shoulder. The rest of the sweepers began to push their brooms faster. Finally, the rebel bent over, snagged his broom from the ground and resumed his work.

The hard-eyed policemen watched the offender a moment longer. Then they walked away. Caesar pulled against the leash in order to see the conclusion of the scene.

Free of his tormentors, the gorilla thrust his broom to the right, the left, scattering the pile of trash he had accumulated. The movements were clumsy, but the rebellion was clear.

The gorilla trudged forward over the litter, an idiotically triumphant grin on his face. He caught up with the line of sweepers, apparently satisfied by his small act of defiance.

Soothing instrumental music provided an aural background to the stunning visual panorama that was fast overloading Caesar’s mind with almost more data than he could sort and understand. He had been marginally aware of the music ever since entering the plaza, but he was jerked to full awareness of it when it ended abruptly.

“Attention! Attention! This is the watch commander. Disperse unauthorized ape gathering at the foot of ramp six!”

Immediately, from all corners of the plaza, pairs of state security policemen began to converge on the run. Through the crowd Caesar glimpsed three chimps and a gorilla, who were doing nothing more sinister than standing at the foot of the ramp, staring mutely at one another. The harshly amplified voice went on.

“Repeat, disperse unauthorized ape gathering at the foot of ramp six. Take the serial number of each offender and notify Ape Control immediately. Their masters are to be cited and fined. Repeat. Their masters are to be cited and fined!”

Instantly the music resumed. The shifting crowds soon hid Caesar’s view of the altercation, but not before he distinctly saw truncheons and metal prods coming up to chest level in the hands of the running policemen.

Behind the indifferent throngs—a few humans bothered to glance around, but most simply moved on—Caesar thought he heard an ape yelp in pain. He couldn’t be sure.

Then, just ahead, he saw a sluggishly moving female orangutan, obviously no longer young. She lowered two shopping baskets to the ground. She placed one hairy hand to her side, as though in pain, searching for a place to rest. A few yards away, at the edge of one of the pocket parks, stood a comfortable sculptured; bench. There was an inscription in black letters across its curving back:

NOT FOR APES.

Staring at the bench, the elderly female wavered. Then she shambled forward. In front of the bench she halted again, staring at the lettering with dull eyes. Finally, with a little cry of pain and another clutch at her side, she turned fully around and lowered herself to the bench.

Her expression suggested to Caesar that she sensed there was something wrong in what she was doing; he was virtually certain she could not have understood the stenciled message.

But the pair of policemen who approached on the double understood it. The younger policeman enforced the warning with two quick whacks of his truncheon.

The female orangutan cringed in pain as the officer snapped, “Off, off!” Then, loudly, his truncheon raised for a third blow: “No! Don’t you see the sign?”

The older lawman was grimly amused. “Take it easy, they can’t read.”

“Not yet they can’t.” The other lifted his truncheon higher. “Off. No!”

In obvious pain, the old female stood up. She lifted her shopping baskets as if each contained great weights. Watching her wobble off, Caesar experienced a mingling of intense pity and equally intense anger. Armando automatically tightened his grip on the leash.

Caesar stepped close to the circus owner, risking a whisper: “You told me humans treated the apes like pets!”

Armando’s dark eyes grew sorrowful. “So they did—in the beginning.”

Through clenched teeth Caesar said, “They have turned them into slaves!”

Armando’s grimace of warning urged Caesar not to speak again. He darted a glance past Caesar’s shoulder, fearful they’d been observed. Apparently they had not, because he said in a low voice, “Be quiet and follow me. I’ll show you what happened.”

The circus owner led Caesar around the far side of one of the miniature parks at the extreme end of the plaza. There, facing the broad paved area where three wide avenues converged, twin pedestals rose. One was crowned by the carved, highly sentimentalized figure of a mongrel dog, the other by a similar treatment of an ordinary house cat.

The animals were identified by respective plaques as “Rover” and “Tabby.” The quotation marks suggested to Caesar that these were symbols, rather than particular animals. The inscription read: In Loving Memory 1982.

Caesar was careful not to let too much of his astonishment show on his features. Armando bobbed his head to suggest they had best move on before he explained.

They entered the tiny park. Armando settled on a bench. Observing the stenciled warning, Caesar remained standing. After a glance to assure himself that no one was seated within earshot, Armando said to his ape companion: “They all died within a few months, nine years ago. Every dog and every cat in the world. It was like a plague, leaping from continent to continent before it could be checked—”

Eyes still roving nervously across the park, Armando waited till a young couple had moved out of sight, then went on.

“The disease was caused by a mysterious virus, apparently brought back by an astronaut on one of the space probes. No vaccine or antidote could be found in time to stop the deaths.”

Caesar was unable to hold back a whispered question: “Then—the disease didn’t affect humans?”

“No, for some reason they were immune. And so, it was discovered, were simians. Even the smallest ones. That is how—” he gestured in a vague, rather tired way toward the bustling plaza “—everything you see began. Humans wanted household pets to replace the ones they’d lost. First the rage was marmosets, tarsier monkeys. Then, as people realized how quickly they learned—how easy they were to train—the pets became larger and larger, until—

He didn’t need to finish. What Caesar had already seen told the story’s end.

“It’s monstrous!” he breathed.

Armando could only nod. “But now you understand why I’ve kept you away until I was reasonably certain you could withstand exposure to all this. I doubt I’d have risked bringing you into a city at all if attendance hadn’t fallen off so sharply these past months. Perhaps the novelty of old-fashioned circuses has faded. Three of the six remaining touring troupes disbanded in the last year and a half. I thought the sight of my star performer distributing flyers might increase the trade—”

Caesar hardly heard, his mind grappling again with the enormity of what had befallen his own kind. Abruptly, he felt the yank of the leash as Armando jumped up. “Come, come!”

They hurried toward an exit on the park’s far side, away from a strolling state security policeman who was staring after them, studying Caesar’s unusual wardrobe.

“All right,” Armando said as they re-entered the busy plaza. “Now you know the worst. Let the shock pass if you can, while we get on with the job.” He forced a smile, accosted a man: “Armando’s Old-Time Circus, sir. Now playing—you’ll enjoy it and so will your little ones.” With a smooth maneuver, he took one of Caesar’s flyers and slipped it into the astonished gentleman’s hand before moving on.

Earnestly trying to obey Armando’s suggestion, Caesar found that he could not. With every few steps, he saw apes subjected to unexpected humiliations, indignities . . .

At an outdoor cafe, they passed a table where a group of female humans were enjoying prelunch cocktails. One of the women popped a slim, pale green cigarette from her perspex case. Instantly, a huge gorilla waiter, a tray of empty glasses in one hand, proffered his lighter with the other.

![Книга Ave, Caesar! [ Аве, Цезарь!] автора Варвара Клюева](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-ave-caesar-ave-cezar-246831.jpg)