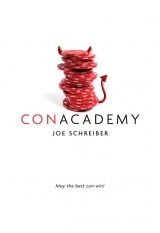

Текст книги "Con Academy"

Автор книги: Joe Schreiber

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

Twenty-Three

THE NEXT DAY IS THE HOMECOMING LACROSSE MATCH. Tuesday’s freak snowstorm is a distant memory, and the manicured field is green and dry. Even though I don’t understand the game, I’m sitting in the stands with a fresh cup of coffee, watching Connaughton trounce the hopeless schmoes from St. Albans, who—even to my uneducated eye—seem to have forgotten which end of the stick to hold on to. The score is already 3–0. Around me the stands are full of parents and alumni dressed in the school colors, drinking their lattes and cheering every play. Six rows down, Brandt and Andrea are side by side, sharing a blanket. I’m not sure what canoodling is, but I’d be willing to bet they’re doing it.

“Can I sit here?”

I look up and see Gatsby standing in front of me. She looks tired, her face pale in the morning light, her hands plunged deep in the pockets of her coat.

“Oh,” I say. “Hey.”

“Listen,” she says, “about last night . . .”

“Yeah.”

“I’m sorry.”

She just stands there. I’m waiting for more, some kind of explanation, but there isn’t anything else. “It’s cool.”

“Thanks.”

“Are you all right? I tried to call . . .”

“I’m fine,” she says.

“Was it some kind of Sigils thing?” I ask. “Like, another test or something? Because, I mean, if that’s what it was . . .”

“No,” she says. “It wasn’t anything like that.”

“Oh. Okay.”

There’s a silence between us that seems to last forever. It’s like there’s this soundproof bubble around us, and the rest of the world is sealed away somewhere on the other side of it, going about its business, remote and unreal. Sometimes that kind of privacy can feel good—intimate, special. Not this time.

“I came by your room,” I say. “I saw the light on.”

“Will.” Gatsby lowers her eyes. “That whole thing. It was a mistake.”

“Which part?”

“When you invited me to the dance . . .” She looks back up at me. “I shouldn’t have said yes.”

“Why not? Is it something I did?”

She shakes her head. “You didn’t do anything.” Somewhere down on the field something happens and the crowd cheers, and we just keep looking at each other.

“Listen,” she says, “I’ll see you around, okay?”

“Sure,” I say, and my voice sounds strange to me, like it’s being piped in from some completely different person.

And I watch her go.

I look down at Brandt and Andrea, snuggling together under the blanket. I couldn’t care less what they’re doing, but I find myself wondering if Brandt’s said anything to her about our trip down to Lowell last night. Then, right on cue, Andrea turns around, looks up at me, and wrinkles her nose.

On the field, it’s halftime, and I see Dr. Melville walking across the playing turf with a microphone. Behind him, a pair of students are carrying out some kind of banner, unfurling it along the field. From here I can see that it’s a flag, deep blue with white and orange bands and a star in the upper left corner.

Which is when I realize that it’s the flag of the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

Which is the last thing I need right now.

“Hello, everyone,” Dr. Melville says. “I’d like to invite a very special student down to talk to you.” He gestures up to the stands, to where I’m sitting. “A young man whose background and ambition are the very definition of the opportunity that Connaughton Academy offers to those with the willingness to advance in the world . . .” He pauses. “Alumni, parents, and faculty, please welcome William Shea.”

The applause is thunderous.

“What is this?” I mutter, rising up slowly on knees that don’t seem to be working quite right, and make my way down the aisle toward the field.

As I walk past Andrea, I feel her reach up and swat me on the butt. I look around at her.

“Did you do this?” I ask.

She grins. “Go get ’em, tiger.”

Twenty-Four

“MANY OF YOU MAY NOT KNOW,” DR. MELVILLE IS SAYING as I make my way out onto the field, “that Mr. Shea comes to us from halfway around the world, hailing from a remote Pacific Island called Ebeye.”

From out in the crowd, I hear a single cackling laugh. I don’t have to look up to know that it’s Brandt. I can tell he’s grinning at me. Dr. Melville ignores the distraction and presses dutifully on.

“I received an email last week from another student asking if Mr. Shea could come up and speak to all of us today about his homeland, about some of the ongoing difficulties that they’ve been facing for the past fifty years since the government began testing nuclear bombs in the Marshall Islands.” Dr. Melville’s voice becomes solemn. “The student who wrote that email is here with us today, and I’d like to invite her down as well.” Turning, he gestures up to the stands again. “Andrea Dufresne?”

More applause. Andrea glides down on it like a pageant queen on a parade float of destiny. “Thank you, Dr. Melville.” She takes the microphone from him and gives me a quick glance out of the corner of her eye—and now I don’t even know her angle. I’ve clearly been snookered so smoothly that I didn’t even realize it was happening, but I don’t even know what else Andrea has up her sleeve.

“As many of you know,” she says, “I’m a scholarship student myself. My parents were U.S. aid workers who lost their lives in the Balkans. I’m attending Connaughton thanks to the gracious support of the administration and alumni endowments. But when I heard about the obstacles that Will has had to overcome after the tragic death of both of his parents—who were flying medicine to an orphanage when their lives were so unexpectedly cut short—and the way that his community came together to send him here for school, well . . . I knew that I’d found not just a kindred spirit for myself, but an inspiration for all of us.” She looks up at the flag. “Will, can you tell us a little bit about your country’s flag?”

As she leans over to give me the microphone. I cup my hand over it, still smiling, and whisper, “I will so get you for this.”

“Sure,” she whispers, and smiles back.

I look up. The crowd has fallen silent, their eyes on me. Over my shoulder I can hear the flag flapping and popping in the breeze.

“This flag . . .” I begin, and take a breath, wondering why I never bothered to learn what “my” flag represented. “Of course, the deep blue symbolizes the ocean. These orange and white stripes you see here are the symbol of hope and . . . ah, good stewardship. And the sun in the corner represents . . . uh . . . the sun. Which is extremely bright in my country. And hot.”

I glance over at Dr. Melville, but he’s not smiling anymore. He actually looks a little confused. Walking over, he takes the microphone from my hand and turns to look at the flag.

“Excuse me, Mr. Shea,” he says, “but when I wrote my doctoral thesis on the Marshall Islands, it was my understanding that the twenty-four-pointed star in the corner is a representation of the twenty-four municipal districts. And the orange and white bands symbolize the Ratak and Ralik chains?” He turns back to me, extending the microphone. “Isn’t that right?”

“Actually,” I say, “no.”

His eyebrows hike up halfway to his hairline. “No?”

“No. Because, you see, the flag was actually redefined last year. All those symbols mean different things now. The government changed it.”

“I’m sorry,” he says. “They changed it?”

I nod. “They took a vote, and the people decided they wanted it to mean something different. It was called the, uh, Cultural Transition Initiative. It’s really fascinating, in fact. You should read up on it.”

“I’ll be sure to do that,” he says, giving me back the microphone and taking a step back, looking more bewildered than ever. Up in the stands, people are beginning to lose interest, and I realize that halftime is going to be over soon but not quite soon enough. As the band marches out onto the field, Andrea steps forward and takes the microphone from me.

“As a special treat,” she says, “Will has volunteered to sing us his country’s national anthem, ‘Forever Marshall Islands.’” She turns to me. “Ready, Will?”

“Actually, I don’t think—”

“Our marching band has already learned the music. Don’t leave us hanging.”

I take her hand. “Only if you join me.”

“I don’t know the words.”

“Just follow my lead,” I say, as the band strikes up a stately tune that sounds oddly similar to “The Star-Spangled Banner” but that must, in fact, be the anthem of my homeland far away. When the moment seems right, I take in a deep breath and begin to sing, with as much gusto as I can manage:

Oh, Marshall Islands,

My home across the sea.

You are a very small island,

Extremely difficult to see.

Most maps don’t include you;

You’re not on any chart.

But oh, Marshall Islands—

You’re always in my heart.

Somewhere across the field, Dr. Melville is shouting something over the music. He doesn’t have a microphone, but I can read lips well enough to know what he’s saying: “Those aren’t the lyrics!” And he’s right, of course—if the person who’d written the actual Marshall Islands national anthem were here now, he’d probably be ready to have me dragged away in chains for a year of cultural awareness training, which, quite frankly, would’ve come in really handy before I’d started telling people I was from there.

I turn to Andrea, who—against almost insurmountable odds—has managed to keep a straight face, and now she joins me in repeating the ridiculous words that I just made up on the spot. We’re going faster now, upping the tempo of the song. Still belting out the lyrics, she spins around to the band conductor, grabs his baton, and swings both arms up in the air, kicking the drum majorettes into triple time as the rest of the band struggles frantically to keep up. Cymbals crash, and the stately anthem accelerates into a Dixieland swing. Our mascot, Colby the Connaughton Cougar, has run out onto the field and starts doing backflips in front of the band.

“You’re not on any chart . . .” Now the lyrics come out sounding like some alternate-universe combination of pep rally and New Orleans funeral. “You’re always in my heart . . .” Andrea pivots around to face the stands. “Come on, everybody,” she shouts, “on your feet! You know this part!”

I look out and I’m amazed at what I see. The music has done something to the students and faculty and alumni, and now they’re on their feet, singing along while Andrea coaches them through it. As Colby the Cougar executes a perfect handspring in front of us, I lean in again and join Andrea for the third chorus. Encouraged by Colby and the response of the Connaughton crowd, the band is now doing some crazy drumline moves that I’m pretty sure nobody’s seen before, and a few of them grab the flag and wave it high in the air. Dr. Melville is now trying to push his way through to grab the microphone, but he can’t get through the majorettes and the color guard. Meanwhile, Andrea and I are bringing it home.

“But oh, Marshall Islands,” we finish together, “you’re always in my heart!” And when the drums and trumpets thunder to a crescendo, the crowd erupts in a roar of spontaneous applause. I realize I’m smiling, and Andrea is too, and I can’t tell if either of us really means it, but at the moment it doesn’t matter. For the moment I’ve forgotten about Gatsby. I’m back in my element, doing what I do best, faking it like a champ, and it feels good.

“Thank you,” Andrea says to the crowd, sounding a little out of breath. Her cheeks are bright red and her eyes are reflecting tiny darts of the early-November sunlight, and when she looks at me, the smile on her face is genuine. “You guys are the best.” She grabs my hand again. “Which is why I know you’re going to be excited when you hear this next part—one week from today, next Saturday, the head of the Ebeye Children’s Health Clinic is going to be here at Connaughton to receive the funds to build a new orphanage on the island that Will Shea calls home.”

“Wait . . .” I stare at her.

My thoughts go spinning in a corkscrew, fluttering to the bottom of my brainpan. Meanwhile, Andrea gestures to the band, and they reach down to unfurl a new banner, which reads: Connaughton Academy Supports the Orphans of Ebeye!

“Many of our alumni have already made some extremely generous pledges,” she says, “including one special pledge from a very special individual that we all know very well.” Turning to the stands, she flicks the hair from her eyes. “Brandt Rush has graciously volunteered to donate fifty thousand dollars.”

Applause. Cheers.

I turn to stare at Andrea again.

Just in time to see her lean in toward me to whisper in my ear.

“Game over, Shea,” she murmurs, still smiling. “You lose.”

Twenty-Five

“WHOA,” THE TWENTY-SOMETHING GUY BEHIND THE monitor says admiringly. It’s Iron Mike Mullen, one of the smalltimers that Uncle Roy brought up from Boston. The screen in front of him reads: Connaughton Alumni for Ebeye. “These people already have their own website.”

I don’t say anything. I’ve got my books spread out on the floor of our rented office space in Lowell, and for some reason that even I don’t understand, I’m trying to study for a U.S. Diplomacy midterm while everybody else scrambles to find a way to salvage the con. Roy’s sitting in the corner, stewing in a robust marinade of his own silence. He’s got a good reason for being furious with me. I wasn’t up-front with him about my bet with Andrea, and now, within a week, we’re going to lose everything.

“Why can’t we just go ahead with the scam?” Dad asks him.

“Because she’ll tip off the mark,” Roy says abruptly. “Haven’t you been paying attention?” He swivels to glare at me. “That was the deal, wasn’t it, William? The part that you didn’t feel compelled to tell us? First one to fifty thousand wins? If she gets the Rush kid to pay out first, she ruins it for us.”

“So what?” Dad shrugs and glances at Rhonda, who’s sitting across from him, painting her fingernails. “So we take the girl out of the equation.”

“Take her out . . . ?” I look at him. “Wait a second, what are you talking about? You can’t—”

“Look,” Dad says. “Let’s get something straight. I know you have a soft spot for this girl, but I’m not allowing your little high school crush ruin our shot at two million bucks. If you think I’m going to let that happen, you’re reading all the wrong books.”

“It’s got nothing to do with—”

“I don’t care. I’m just saying, we take care of her.”

Uncle Roy gets up and walks over to Dad. “What are you saying?”

“We send her packing,” Dad says. “This is our deal. She wants to keep trying to fleece these millionaires for some made-up charity for a bunch of orphans, then that’s her thing, but we’re going to finish this.”

“She’ll tip off Brandt.”

Dad shakes her head. “Then we don’t give her that chance. We shut her down. Hard.”

I stand up. “No.”

“No?” He’s getting that look now, darkness gathering across his face, falling over his eyes like the shadow of an object dropping fast. Seeing him like this gives me a bright coppery taste in my mouth that I associate with early childhood, the old familiar panic of powerlessness.

“Nobody’s getting hurt,” I say. “This isn’t that kind of deal.”

Dad moves right up close to me and stands directly in front of my face. Whiskey fumes stream invisibly from his nostrils. Everybody else in the office has stopped what he’s doing to watch us. When Dad speaks, the words are little more than a snarl.

“Listen to me, junior. I taught you everything you know about the long con. We’re all here because of what you promised us.”

“No,” I say, “you’re here because you’re a drunk and you’re too irresponsible to make it on your own. I didn’t want you here. Ever since you showed up, all you’ve done is ruin everything.”

“Easy, boy.” Dad’s voice is ominously quiet. “Don’t say things that you’re gonna regret when we get back home to Trenton.”

“I’m never going back to Trenton,” I say, and for a long second, the words just hang there.

“What?”

“You heard me.” My heart is pounding and I force myself to stand my ground. “I can fix this situation myself. I worked too hard to get where I am now. This is my life. I’m not going back.”

Dad shoves me backwards. I don’t see it coming, and the thrust propels me into an empty desk, where I whack my skull on the arm of a chair before hitting the ground. I start to shake off the pain, but Dad is lunging again, landing on top of me with his fist cocked back, and it’s only because of Uncle Roy pulling him off that I don’t catch his knuckles across the bridge of my nose.

Roy’s old, but he’s tough. He tosses Dad aside like a sack of dirty laundry. Dad starts to stand up, and Roy fixes him with a look that says: Try it.

“You come at me like that again, Roy,” Dad says in a low voice, “you better bring a gun.”

“Shut your cake hole,” Uncle Roy says. “Nobody’s doing anything with guns.” He pronounces that last word with the disdain of a man who regards such things as the last resort of the desperate and incompetent, guys too knuckleheaded to handle themselves any other way. Pausing to collect himself, Roy tucks in his shirt, pulls out a comb, and runs it through his hair. “Okay, now, listen. Everybody just breathe. We all know the situation isn’t optimal. That doesn’t mean it’s hopeless.” He points at me. “William, your dad’s right about one thing. You got us into this, you’re going to get us out.”

“Damn straight,” Dad says.

Roy holds up a hand. “Today’s Monday. Now, my understanding is that the Rush kid isn’t writing his fifty-grand check for the orphans of Ebeye until Saturday, am I right?”

I nod. “That’s right.”

“So all we have to do is get him back here in this office, cash in hand, sometime before then.”

“He wants another ten-thousand-dollar trial run,” I say.

Uncle Roy shakes his head. “That’s impossible—we’re out of time. You need to convince him that if he’s going to take down McDonald, then he needs to place that big bet before Saturday.”

“How am I supposed to do that?”

“Hey, you’re a smart kid,” Uncle Roy says cheerfully, gesturing at the textbooks and notes I’ve got scattered around the floor. “You’ll figure something out.”

Twenty-Six

I WAKE UP IN THE MORNING FEELING EXHAUSTED. I DIDN’T sleep well at all—I know it’s my imagination, but I swear I can feel Dr. Melville’s counterfeit Bible tucked under my box spring like some fractured fairy tale version of the princess and the pea. Imaginary or not, the lump wouldn’t bother me so much if it didn’t remind me of Gatsby, who I haven’t heard from since the lacrosse game. Meanwhile, it’s seven a.m., and I’ve got a U.S. Diplomacy midterm in an hour that I couldn’t feel less prepared for. I grab a coffee from the Starbucks in the arts center, take a big gulp of French roast, and head off to class.

The exam goes even worse than I had feared. From the moment I look down at the essay question on Wilson’s Fourteen Points, my mind goes blank. People around me are already scribbling fiercely, the room full of the sound of scratching pencils, while I spend an hour staring at the empty page, wondering how on earth I ever thought I could fit in here.

With five minutes left on the clock, I toss the blue book onto the teacher’s desk and walk out the door.

I’m sitting in the dining hall, staring out the window, when Gatsby takes a seat next to me.

“Will, we need to talk.”

“Look,” I say, “it’s okay. You don’t need to say anything.”

“Just let me explain, okay?”

I look at her and nod.

“I’ve never been invited to Homecoming before,” Gatsby says. “When you invited me, I was really excited. I had been hoping you’d ask me.”

“So . . . ?”

She closes her eyes, opens them again. “There was this boy back on the Vineyard. His name was Del James. He was a baseball player, and I had this huge crush on him. We had this middle school Valentine’s Day dance, and he invited me. At first I couldn’t believe it—it seemed too good to be true. My friends all told me that I had to say yes.”

I don’t say anything. I can already see where this is going and I don’t want to hear it, but it’s too late.

“I got a new dress and new shoes,” Gatsby says, “and my dad paid for me to get my hair done at this fancy salon in Boston. I remember looking in the mirror and feeling so grown up.” She stops and swallows and looks up at me. “But when I got to the dance, Del just looked at me and started laughing. He told me he’d only done it on a dare. His friends had bet him that he wouldn’t ask out the ugliest girl in the class. They all thought it was hilarious. The worst part—” Gatsby stops and takes in a little breath. “He convinced my own friends to encourage me to go. Everybody was in on it except for me.”

“Gatsby,” I say, and my mouth feels as dry as sand, “I’m sorry.”

“No,” she says, “it’s not your fault. As I was getting ready the other night, I just kept thinking, What if it happens again?” She reaches over and touches my hand. “But you’re different, Will. I see that.”

I can’t look at her.

“I know how well things are going for you,” she says. “With Rush making that donation to your orphanage, and all the increased awareness that’s going on about the situation in Ebeye, you’ve got to be so excited.”

“It’s not that big a deal.”

“Yes it is.” She holds up her hand to stop me from interrupting. “Will, look at me. You’ve seen poverty and privation that none of us can imagine. You grew up in the poorest area of the Pacific, and your parents literally gave their lives to serve others. You’ve got every right to be bitter and discouraged, but instead you’re decent and optimistic and fair. When I think about it, you’re the perfect antidote to the Brandt Rushes of the world.”

“Yeah,” I mumble. “It’s great.”

“It is,” she says. “And okay, I know Andrea’s the one who initiated the fundraiser, and it’s exactly the sort of project that she’d undertake just to pad her college application, but with the money that’s coming in to help your island—”

“It’s not my island.”

“Well, yes, obviously it’s not your island, but it is your home. You grew up there, and—”

“You’re not listening to me,” I say, a lot more sharply than I had intended. “It’s not my home.”

Across the table, Gatsby regards me peculiarly. “What are you saying?”

The silence between us stretches out for an unreal amount of time. Far off, I hear the clink of silverware and ice. Deep inside, I can already feel something rising into my throat. It’s sharp and angular and unpleasant, and that’s when I realize that it’s the truth. A cowardly voice pipes up from inside me.

If you tell her this, you’ll ruin everything.

Too late for that now.

“What if I told you”—I take in a breath and let it out, making myself look her in the eye—“that I wasn’t really from some island in the Pacific?”

And everything stops. Gatsby blinks and shakes her head a little. “What?”

“What if I told you that I’m really just a kid from New Jersey, and this whole thing about my parents being missionaries and dying in a plane crash was just a story that I made up so that I could go to school here?”

“I don’t understand.” Now Gatsby’s just staring at me. “You’re saying you’re not from the Marshall Islands?”

“I’m from Trenton, New Jersey. My real name is Billy Humbert. This is the third school that I’ve sneaked into in two years.”

“You’re from . . . New Jersey,” she repeats slowly, like she’s just trying to get the facts straight in her own mind. “How did you . . .”

“I forged my transcripts. Faked my letters of recommendation. Hacked into the school’s database and gave myself a whole new history.” I pause. “Gatsby, look, I know it was wrong. I never wanted to lie to you about all of this, I swear.”

She’s already pushing herself back, standing up, leaving her tray on the table. She doesn’t say anything. The look on her face is the worst part. The way that she just keeps staring at me.

“Gatsby, wait.”

But she’s walking away. I go after her, following her out of the dining hall. “I can explain everything,” I say, but that’s just another lie, because no amount of explanation is going to excuse what I did or help her understand why, and it’s far too late anyway.

Running around the corner, I almost collide with George the Kant-reading security guard.

“Shea,” he says. “Come with me.”

“Not right now.”

“Right now.” He reaches down and takes hold of my arm. “Dr. Melville wants to talk to you. He says it’s important.”