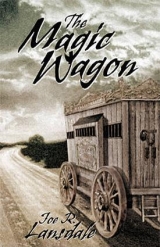

Текст книги "The Magic Wagon"

Автор книги: Joe R. Lansdale

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

CHAPTER 2

It was a hot day already and I thought about that and wished I'd left Rot Toe's tarp up. Sweat was coming from beneath the brim of my cap and streaming down my face, running into the edge of my mouth. It tasted like salt, dirt, and sadness, mostly sadness, because sweat always reminds me of tears.

There was the smell of animal lots on the warm wind, and it wasn't too bad. Not bad like some of the cow towns we'd been in. So bad in some that the stink made you have to lean over and throw up what you'd eaten. This was small town animal stink, not the months old, ankle-deep mess of a Kansas cow lot. In fact, it was almost pleasant. Reminded me that I was once again in my old stomping grounds, East Texas, and that the place where I'd grown up wasn't all that far away.

And though I didn't want to think on it, that barnyard smell took me back a few years, back to the baddest old winter we'd ever seen, the winter I came to believe in signs and omens. The winter I turned fifteen.

***

It had come a rare snow that year, and even rarer for East Texas it had actually stuck to the ground and got thick. Along came the wind, colder than ever, and it turned the snow to ice. It was beautiful, like sugar-and-egg-white icing on a cake, but it wasn't nothing to enjoy after the excitement of first seeing it come down. I had to get out in it and do chores, and that made me wish for a lot of sunshine and a time to go fishing.

Third day after it snowed and things had gotten real icy, I was out cutting firewood from the woodlot and I found a madman in a ditch.

I'd already chopped down a tree and was trimming the limbs off of it, waiting for Papa, who was coming across the way with a crosscut so we could saw it up into firewood sizes. While I was trimming, I heard a voice.

"Got a message. Get out of this ditch, I got a message."

Clutching the axe tight, I went over and looked in the ditch, and there was a man lying there. His face was as blue as Mama's eyes, and Papa says they're so blue the sky looks white beside them, even on its best day. His long, oily hair had stuck to the ground and frozen there so that the clumped strands looked like snakes or fat worms trying to find holes to crawl into. There were icicles hanging off his eyelids and he was barefoot.

I screamed for Papa. He tossed down the saw and came running fast as he could on that ice. We got down in the ditch, hauled the fella up, pulling out some of his frozen hair in the doing. He was wearing a baggy old pair of faded black suit pants with the rear busted out, and his butt was hanging free and drawerless. It was darker than his face, looked a bit like a split, overripe watermelon gone dark in the sun. His feet and hands were somewhere between the blue of his face and the blue-black of his butt. The shirt he had on was three sizes too big, and when Papa and I had him standing, the wind came a-whistling along and flapped the fella s shirt around him till he looked like a scarecrow we were trying to poke in the ground.

We got him up to the house, and stretched him out on the kitchen table. He looked like he'd had it. He didn't move an inch. Just laid there, eyes closed, breathing slow.

Then, all of a sudden, his eyes snapped open and he shot out a bony hand and grabbed Papa by the coat collar. He pulled himself to a sitting position until his face was even with Papa's and said, "I got a message from the Lord. You are doomed, brother, doomed to the wind, cause it's gonna blow you away." Then he closed his eyes, laid back down and let go of Papa's shirt.

"Easy," Papa said. But about that time the fella gave a shake, like he was having a rigor, then he went still as a turnip. Papa felt for a pulse and put his ear to the scarecrows chest, looking for a heartbeat. From the expression on Papa's face, I could tell he hadn't found any.

"He's dead, Papa?"

"Couldn't get no deader, son," Papa said, lifting his head from the man's chest.

Mama, who'd been standing off to the side watching, came over. "You know him, Harold?" she asked.

"Think this is Hazel Onin's son," Papa said.

"The crazy boy?" she said.

"I just seen him once, but I think it's him. They had him on a leash out in the yard one summer, had this colored fella leading him around, and the boy was running on all fours, howling and trying to lift his leg to pee on things. His pants was all wet."

"How pitiful," Mama said.

I knew of Hazel Onin's boy, but if he had a name I'd never heard it. He'd always been crazy, but not so crazy at first they couldn't let him run free. He was just considered mighty peculiar. When he was eighteen he got religion worse than smallpox and took to preaching.

Right after he turned twenty, he tried to rape a little high yeller gal he was teaching some Bible verses to, and that's when the Onins throwed him in that attic room, locked and barred the windows. If he'd been out of that room since that time, I'd never heard of it, other than what Papa had said about the leash and wetting himself and all.

I'm ashamed of it now, but when I was twelve or thirteen, me and some other boys used to have to walk by there on our way to and from school, and the madman would holler out from his barred windows at us, "Repent, cause you all gonna have a bad fall," then he'd go to singing some old gospel songs and it gave me the jitters cause there was an echo up there in that attic, and it made it seem that there was someone else singing along with him. Someone with a voice as deep and trembly as Old Man Death might have.

Freddy Clarence used to pull down his pants, bend over, and show his naked butt to the madman's window, and we'd follow his lead his lead on account of not wanting to be called a chicken. Then we'd all take off out of there running, hooping and hollering, pulling our pants and suspenders up as we ran.

But we'd quit going by there a long time back, as had almost everyone else in town. They moved Main Street when the railroad came through on the other side, and from then on the town built up over there. They even tore down and rebuilt the schoolhouse on that side, and there wasn't no need for us to come that way no more. We could cut shorter by going another way. And after that, I mostly forgot about the madman prophet.

"It's such a shame," Mama said. ''Poor boy."

"It's a blessing, is what it is," Papa said. "He don't look like he's been eating so good to me, and I bet that's because the Onins ain't feeding him like they ought to. They figure him a shame and a curse from God, and they've treated him like it was his fault his head ain't no good ever since he was born."

"He was dangerous, Harold," Mama said. "Remember that little high yeller girl?"

"Ain't saying he ought to have been invited to no church social. But they didn't have to treat him like an animal."

"Guess it's not ours to judge," Mama said,

"Damn sure don't matter now," Papa said.

"What do you think he meant about that thing he said, Papa?" I asked. "About the wind and all?"

"Didn't mean a thing, son. Boy didn't have a nut in his shell is all. Crazy talk. Go on out and hitch up the wagon and I'll get him wound up in a sheet. We'll take him back to the Onins. Maybe they'll want to stuff him and put him in the attic window so folks can see him as they walk or ride by. Maybe they could charge two bits to come inside and gawk at him. Pull his arm with a string so it looks like he's waving at them."

"That's quite enough, Harold," Mama said. "Don't talk like that in front of the boy."

Papa grumbled something, went out of the room for a sheet, and I went out to the barn and hitched the mules up. I drove the wagon up to the front door, went in to help Papa carry the body out. Not that it really took both of us. He was as light as a big, empty corn husk. But somehow, the two of us carrying him seemed a lot more respectable than just tossing him over a shoulder and slamming him down in the wagon bed.

We took the body over to the Onins, and if they were broke up about it, I missed the signs. They looked like they'd just finally gotten some stomach tonic to work, and had made that long put off and much desired trip to the outhouse.

Papa didn't say nothing stern to them, though I expected him to, since he wasn't short on honest words. But I figure he didn't see any need in it at that point. The fella was dead.

Mrs. Onin stood in the doorway all this time, didn't come out to the wagon bed while the body was there. After Mr. Onin unwound the sheet and took a look at the madman's face, said what a sad day it was and all, he asked us if we'd mind putting the body in the toolshed.

We did, and when we got back to the wagon, Mrs. Onin was waiting by it. Mr. Onin offered us a dollar for bringing the body home, but of course, Papa didn't take it.

Before we climbed up on the wagon, Mrs. Onin said, "He’d been yelling from upstairs all morning, saying how an angel from God wearing a suit coat and a top hat had brought him a message he was supposed to pass on. Kept saying the angel was giving him a test to see if he deserved heaven after what he'd done to that little girl."

Papa climbed on the wagon, took hold of the lines. With his head, he motioned me up.

"Then we didn't hear nothing no more," Mr. Onin said. "I went up there to check on him and he'd pulled the bars out of one of the windows and got out. I don't reckon how he did that, as he'd never been able to do it before, and them bars was as sturdy as the day I put them in, no rotten wood around the sills or nothing."

Papa had taken out his pocket knife and tobacco bar, and he was cutting a chaw off of it. "Reckon you went right then to the sheriff to tell him your boy run off," Papa said, and there was an edge to his voice, like when he finds me peeing out back too close to the house.

"Naw," Mr. Onin said, looking at the ground, "I didn't. Figured cold as it was, he'd come back."

"Don't matter none now, does it?" Papa said.

"No," Mr. Onin said. "He's out of his misery now."

"Them's as true words as you've spoke," Papa said.

"I'll be getting that sheet back to you," Mr. Onin said.

"Don't want it," Papa said. He clucked up the mules and we started off.

When we were out of earshot of the house, I said, "Papa, you reckon they thought that crazy fella would go back cause he was cold?"

"Why in hell would he want to go back to that attic? Even if it might have been warm."

We didn't say anything else until we got home, then wasn't none of the talking about the madman or the Onins. Mama didn't even mention it after she saw Papa's face.

Just before supper, Papa went out on the porch to smoke his pipe, and I went out to the barn to toss some hay to the mules and the milk cow. I was tossing it, smelling that animal smell, thinking about how it reminded me of my whole life, that smell. Reminded me of Mama and Papa, warm nights with very little breeze, cold nights with the fire stoked up big and warm, late suppers, tall tales in front of the fireplace, standing on the porch or looking out of the windows at the morning, noon or night, spring, summer, fall, or winter. And that smell, always there, like a friend who had some peculiar, if not bad-smelling, toilet water. It was in the floorboards of the house, on the yard, thick in the barn. A smell that even now moves me backwards and forwards in time, confuses me on which are the truths and which are the lies of my memory.

So there I was, throwing hay, thinking this fine life would go on forever, and all of a sudden, I felt it before it happened.

I quit tossing hay, turned to look out the barn door. It was like I was looking at a painting, things had gone so still. The sky had turned yellow. The late birds quit singing and the mules and the milk cow turned their heads to look outdoors too.

Way off I heard it, a sound like a locomotive making the grade, burning that timber. Only there wasn't a track within ten miles of us. Outside the sky went from yellow to black, from still to windy. Pine straw, dust and all manner of things began whipping by. I knew exactly what was happening.

Twister.

I dropped the pitchfork, dove for the inside of an old shovel-scoop mule sled, and no sooner had I hit face-down and put my hands over my head, then it slammed into the barn.

I caught a glimpse of a cow flying by, legs splayed like she thought she could stop the tug of the wind easy as she could stop the tug of a rope. Then the cow was gone and the sled started to move.

After that, everything happened so quickly I'm not certain what I saw. Lots of things flying by, for sure, and I could hardly breathe. The sled might have gone as high as thirty feet, cause when I came down it was hard. Hadn't been for the ice, I'd probably have been driven into the ground like a cork in a bottle. But the sled hit the ice at an angle and started sliding, throwing up dirty, hard snow on either side of me. Pieces of ice hit me in the face and the sled fetched up against something solid, a stump probably, and I went flying out of it, hit the ice, whirled around like a fly in a greasy skillet, came to rest in the ditch where I'd found the madman.

I passed out for a while, and I dreamed. Dreamed I was in the sled again, flying through the air, and there was our house, lifting up from the ground, floor and all. It flew right past me, rising fast. When it moved in front of me, I glimpsed Mama. She was standing at the window. All the glass was blown out, and she was clinging to the sill with both hands. Her eyes were as big and blue as her china saucers, and her red hair had come undone and was blowing and whipping around her head like a brush fire.

The house shot on up, and when I looked up to see, there wasn't nothing but whirling blackness with little chunks of wood and junk disappearing into it.

"Mama," I said, and I must have said it a lot of times, cause that's what brought me to. The sound of my own voice calling Mama.

I tried to stand, but my ankle wasn't having it. It hurt like hell, and when I looked down, I saw my boot and sock had been ripped off by the blow, and the ankle was as big as a coiled cottonmouth snake.

I put a hand on the edge of the ditch, dug my fingers through the ice, and pulled myself up, taking some of the skin off my naked foot as I did. It was so cold the flesh had frozen to the ground and it had peeled off like sweet-gum bark.

Once I was out of the ditch, I started crawling across the ice dragging my useless foot behind me. Little chunks of skin came off my palms, so I had to pull myself forward on my coat-sleeved forearms.

I hadn't gone far before I found Papa. He was sitting in his rocking chair, and in one hand he held his pipe and it was still smoking. The porch the chair had been sitting on was gone, but Papa was rocking gently in what was left of the wind. And the pitchfork I'd tossed aside before diving into the sled was sticking out of his chest like it had growed there. I didn't see a drop of blood. His eyes were open and staring, and every time that chair rocked forward, he seemed to look and nod at me.

Behind Papa, where the house ought to have been, wasn't nothing. It was like it hadn't never been built. I quit crawling and started crying. Did that till there wasn't nothing in me to cry, and the cold started making me so numb I just wanted to lay there and freeze at Papa's feet like an old dog. I felt like if I wasn't his killer, I was at least a helper in the murder, having tossed down the very pitchfork the twister had thrown at him.

It started to rain little ice pellets, and somehow the pain of those things pounding on me gave me the will to crawl toward a heap of hay that had been chunked there by the wind. By the time I got to the pile and looked back, Papa wasn't rocking no more. Those runners had froze to the ground and his black hair had turned white from the ice that had stuck to it.

I worked my way into the hay and tried to pull as much of it over me as I could. Doing that wore me completely out, and I fell asleep wondering about what had happened to Mama, hoping she was still alive.

The wind picked up again, took most of the hay away, but by then I didn't give a damn. I awoke remembering that I'd had that dream about Mama and the house again. Even though I didn't have much hay on me, it didn't seem so cold anymore. I figured it was either warming up, or I was getting used to it. Course, wasn't neither of them things. I was freezing to death, and would have too, if not for Mr. Parks and his boys.

Mr. Parks was our nearest neighbor, about three miles east. Turned out he had been chopping wood when the sky went yellow. Later he told me about it, and he said it was as strange as a blue-eyed hound dog, and unlike any twister he'd ever seen. Said the yellow sky went black, then this dark cloud grew a tail and came a-waggin' out of the heavens like a happy dog, getting thicker as it dipped. When it touched down, he figured the place it hit was right close to our farm, so he hitched up a wagon and came on out.

It was slow go for him and his two boys, on account of the ice and them having to stop now and then to clear the road of blown-over trees and a dead deer once. But they made it to our place about dark, and Mr. Parks said first thing he jaw was Papa in that rocker. He said it was like the stem of papa's pipe was pointing to where I lay, partly in, partly out that hay.

They figured me for croaked at first, I looked so bad. But then they saw I hadn't gone under, they loaded me in the wagon, covered me in some old feed sacks and a couple of half-wet blankets, and started out of there.

That foot of mine was broke bad. The doctor came out to the Parks' place, set it, and didn't charge me a cent. He said that was on account of he owed Papa for a bushel of taters from last fall, but I knew that was just one of them friendly white lies. Doc Ryan hadn't never owed nobody nothing.

Mr. and Mrs. Parks offered me a place to stay after the funeral, but I told them I'd go back to our place and try and make a go of it there.

Johnny Parks, who used to whip the hell out of me twice a week on them weeks we both managed to go a full week to school, made me a pair of solid crutches out of hickory, and I went to Papas funeral on them.

Mama, as if there was something to my dream, wasn't never found, and for that matter, they couldn't hardly find no pieces of the house. There was plenty of barn siding around, but of the house there was only a few floorboards, some wood shingles, and some broken glass. Maybe it's silly, but I like to think that old storm just come and got her and hauled her off to a better place, like that little gal in that book The Wizard of Oz.

Mr. Parks made Papa a tombstone out of a piece of river slate, chiseled some nice words on it: HERE LIES HAROLD FOGG, KILT BY A TORNADER? AND HERE LIES THE MEMRY OF GLENDA FOGG WHO WAS CARRIED OFF BY THAT SAME TORNADER AND WASNT NEVER FOUND, NOT EVEN THE PIECES.

Beneath that were some dates on when they was born and died, and a line about them being survived by one son, Buster Fogg, meaning me, of course.

Over the protests of Mr. and Mrs. Parks, I had them take me out to our place and I set up a tent there. They left me a lot of food and some hand-me-down clothes from their boys, then they went off saying they'd be back to check on me right regular. Mrs. Parks cried some and Mr. Parks offered me some money and the loan of his mule, but I said I had to think on it.

This tent Mr. Parks gave me was a good one, and I managed to get around well enough on my crutches to gather barn siding and what tools and nails I could find, and I built a floor in it. I could have got Mr. Parks and his boys to do that for me, but I couldn't bring myself to it, not after all they'd done. And besides, I had my pride. Matter of fact, now that I think on it, that was about all I had. That and the place.

Well, it took me a couple of days to do what should have taken a few hours on account of having to pull nails out of boards and reuse them, but I got the tent fixed up real good and cozy finally. It wasn't no replacement for the house and Mama and Papa, but it was better than stepping on a tack or getting jabbed in the eye with a pointed stick.

I wished I could have turned back time some, been in our house. I'd even have liked to have heard Mama fussing over how much firewood Papa should have laid in, which was one of the few things he was always a little lazy on, and was finally glad to pass most of the job along to me. I could hear Mama telling him as she looked at the last few sticks of stove wood, "I told you so."

On the morning after I'd spent my first night on my finished floor, I got up to take a good look at things, and see at what I could manage on crutches.

There were dead chickens lying about, like feather dusters, pieces of wood and one mule lying on his back, legs sticking up in the air like a table blowed over. Didn't see a sign of the other mule or the cows.

Wasn't none of this something I hadn't already seen, but now with the flooring in, and my immediate comfort taken care of, I found I just couldn't face picking up dead chickens and burning a mule carcass.

I went back inside the tent and felt sorry for myself as that's all there was to do, besides eat, and I'd done that till I was about to pop. I wasn't such a great reader, but right then I wished I had me a book of some kind, but what books we'd had had been blowed away with the house.

About a week went by, and I'd maybe got half the chickens picked up and tossed off in the ditch by the woodlot, and gotten the mule burned to nothing besides bones, when this slick-looking fella in a buckboard showed up.

"Howdy there young feller," he said, climbing down from his rig. "You must be Buster Fogg."

I admitted I was, and up close I seen that snazzy black suit and narrow brim hat he had on were even snappier than they'd looked at a distance. The hat and suit were dark as fresh charcoal, and the pants had creases in them sharp enough to cut your throat. And he was all smiles. He looked to have more teeth than Main Street had bricks.

"Glad to catch you home," he said, and he took off his hat and held it over his chest as if in silent prayer.

"Whatsit I can do for you?" I asked. "Maybe you'd like to come in the tent, get out of this cold?"

"No, no. What I have to say won't take but a moment. My name is Purdue. Jack Purdue. I'm the banker from town."

Well, right off I knew what it was and I didn't want to hear it, but I knew I was going to anyhow.

"Your father's bill has come due, son, and I hate it something awful, and I know it's a bad time and all, but I'm going to need that money by about"-he stopped for a moment to look generous-"say noon tomorrow. Least half."

"I ain't got a penny, Mr. Purdue," I said. "Papa had the money, but everything got blowed away in the storm. If you could just give me some time-"

He put his hat on and looked real sad about things, almost like it was his farm he was losing.

"I'm afraid not, son, It's an awful duty I got, but it's my duty."

I told him again about the money blowing away, how Papa had saved it up from selling stuff during the farm season, doing odd jobs and all, and that I could do the same, providing he gave my leg time to heal and me to get the work. Just to play on his sympathy some, I then went on to tell him the whole horrible truth about how Papa was killed and Mama blowed away like so much outhouse paper, and when I got through I figured I'd told it real good, cause his eyes looked a little moist.

"That," he said, not hardly able to speak, "is without a doubt the saddest story I've ever heard. And of course I knew about it, son, but somehow, hearing it from you, the last survivor of the Fogg family, makes it all the more dreadful."

He kind of choked up there on the end of his words, and I figured I had hold of him pretty good, so I throwed in how us Foggs had pride and all, and that I'd never let an owed bill go unpaid, and if he'd just give me the time to raise the money, he'd have it in his hand before long.

He told me he was tore all to hell up about it, but business was business, sad story or not. And as he wiped some tears out of his eyes with the back of his hand, he told me he would give me until tomorrow evening instead of noon, because he reckoned someone who'd been through what I had deserved a little more time.

"But that ain't enough," I said.

"Sorry, son, that's the best I can do, and that goes against the judgment of the bank. I'm sticking my neck out to do that."

"You are the bank, Purdue," I said. "Who you fooling? It ain't me. We all know you're the bank."

"I understand your grief, your great torment," he said, just like one of the characters from some of them dime novels Papa bought from time to time, "but business is business."

"You said that."

"Yes I did, young sir." With that, Purdue turned and walked back to his buckboard. He called out to me as I stood there leaning defeated on my crutches. "I tell you, son, that is the saddest story I've ever heard, and I've heard some. Tragic. This will hang over my head like the shining sword of Damocles from here on out, right over my head," he showed me exactly where it would be hanging with his hand, "until my dying day."

He stood there with one foot on the buckboard step a moment, looking as downcast as a young rooster without any hens, then he climbed up and cracked the whip gently over the heads of the horses. There must have been some pretty heavy tears in his eyes as he left, cause when he turned the buckboard around, the left wheels rolled right across Papa's grave.

My farming days were over before they even got started. And I'll tell you, right then and there, I decided I wasn't going to pick up another dead chicken to make the place look nicer. In fact, I went over to the ditch, got the ones I'd throwed down there out and chunked them around sorta like they'd been. Then I went back to my tent and wished I hadn't burned that old dead mule up. It was all mighty depressing.

The smartest thing to have done was go on over to Mr. Parks's place, even if it did take me all damned day on crutches, but I just couldn't. Us Foggs had our pride and I didn't want no handout. No one taking care of me when I was old enough to take care of my ownself, I decided to set out for town, get me a job there, make my own way. Even if I couldn't save the farm, I could start me some kind of living. There was probably something I could work at until my leg healed up and I got me a solid job.

I figured if I started early, like tomorrow morning, I could make town by nightfall, crutches or not. I'd most likely fall down and bust it a few times, but that didn't matter none.

Well, as I said, us Foggs are proud, and maybe just a bit stupid, so come morning I put some hard bread, jerked meat, and dried fruit in a sack, and saying adios to the dead chickens, the mule bones, and Papa's grave, I started crutching on out of there.

I must have fallen down a half-dozen times before I got to the road, but when I was on it I could crutch along better because there was a lot less ice there.

By noon my underarms were so sore from the rubbing of the crutches, they were bleeding and making blisters that kept popping as I went. Instead of making it to town by nightfall, I was beginning to think I'd be lucky to make it by next year's Thanksgiving. In fact, I was counting on dying at that moment, just keeling over beside the road there and kicking out the last of my worries.

I stopped, sat down on a rock and my coattails, ate some bread and jerky, and fretted things over. Thinking back on it now, I'm surprised I didn't hear it coming before I did. Guess I was wrapped up in my lunch and my thinking. But I finally caught sound of this tinkling, and when I looked up I seen it was bells and harness I had heard, and the harness was attached to eight big mules pulling a bright, red wagon driven by a big colored man wearing a long, dark coat and a top hat. When the sun hit his teeth they flashed like a pearl-handled revolver.

As the wagon made a little curve in the road, I got a glimpse at the side, and I could see there was a cage fixed there, balancing out the barrels of water and supplies on the other side.

At first, I thought what was in the cage was a deformed colored fella, but when it got closer, I seen it was some kind of animal covered in black fur. It was about the scariest, ugliest damned thing I'd ever seen.

Right then I was feeling a mite less proud than I had been earlier that morning, so I got them crutches under my sore arms and hobbled out into the road waving a hand at the wagon. I was aiming on getting a ride or getting run slap over so I could end the torture. I didn't feel like I could crutch another mile.

The wagon slowed and pulled alongside me. The driver yelled, "Whoa, you old ugly mules," and the harness bells ceased to shake.

I could see the animal in the cage good now, but I still couldn't figure on what it was. There was some yellow words painted above the cage that said, "THE MAGIC WAGON," and to the right of the cage was a little sign with some fancy writing on it that read: "Magic Tricks, Trick Shooting, Fortune Telling, Wrestling Ape, Side Amusements, Medicine For What Ails You, And All At Reasonable Prices."

Sounded pretty good to me.

"You look like you could use a ride, white boy," the big man said.

"Yes sir, I could at that," I said.

"You don't yes-sir a nigger." I turned to see who had said that, and there was this fella standing in faded, red long Johns and moccasins with blond hair down to his shoulders and a skimpy little blond mustache over his lip, He had his arms crossed, holding his elbows against the cold. He'd obviously come out of the back of the wagon, but he'd walked so quiet I hadn't even known he was there till he spoke.

When I didn't say nothing, he added, "This here's my wagon. He's just a nigger that works for me. I say who ride and who don't, and I say you don't."

"I got some jerky, canned taters, and beans I can trade fo a ride, and I'll sit up there on the seat."