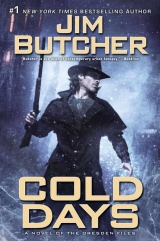

Текст книги "Cold Days"

Автор книги: Jim Butcher

Соавторы: Jim Butcher

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter

Thirteen

“Grasshopper,” I said, feeling myself smile. “Illusion. Very nice.”

Molly gave me a little bow of her head. “It’s what I do.”

“Also good timing,” I said. “Also, what the hell? How did you know I was . . . ?”

“Alive?”

“Here, but sure. How did you know?”

“Priorities, boss. Can you walk?”

“I’m good,” I said, and pushed myself to my feet. It wasn’t as hard as it really should have been, and I could feel my endurance rebuilding itself already, the energy coming back into me. I was still tired—don’t get me wrong—but I should have been falling-down dizzy and I wasn’t.

“You don’t look so good,” Molly said. “Was that a tux?”

“Briefly,” I said. I eyed the car. “Feel like driving?”

“Sure,” she said. “But . . . that’s pretty stuck, Harry, unless you brought a crane.”

I grunted, faintly irritated by her tone. “Just get in, start it, and give it gas gently.”

Molly looked like she wanted to argue, but then she looked down abruptly. A second later, I heard sirens. She frowned, shook her head, and got into the car. The motor rumbled to life a second later.

I went down the stairwell where the car’s tires were stuck, set down Bob’s skull, and found a good spot beneath the rear frame. Then I set my feet, put the heels of my hands against the underside of the Caddy, and pushed.

It was hard. I mean, it was really, really gut-bustingly hard—but the Caddy groaned and then shifted and then slowly rose. I was lifting with my legs as much as my arms, putting my whole body into it, and everything in me gave off a dull burn of effort. My breath escaped my lungs in a slow groan, but then the tires were up out of the stairwell, and turning, and they caught on the sidewalk and the Caddy pulled itself the rest of the way.

I grabbed the skull, still with the mostly limp Toot-toot inside it, staggered back up out of the stairwell and into the passenger side of the car. I lifted my hand and sent a surge of will down through it, muttering, “Forzare,” and the overstrained windshield groaned and gave way, tearing itself free of the frame and clearing Molly’s vision.

“Go,” I grated.

Molly went, driving carefully. The emergency vehicles were rolling in past us, and she pulled over and drove slowly to let them by. I sat there breathing hard, and realized that the real effort of moving that much weight didn’t hit you while you were actually moving it—it came in the moments after, when your muscles recovered enough to demand oxygen, right the hell now. I leaned my head against the window, panting.

“How’s it going, buddy?” I asked a moment later.

“It hurts.” Toot sighed. “But I’ll be okay, my lord. The armor held off some of the blow.”

I checked the skull. The eyelights were gone. Bob had dummied up the moment Molly was around, as per my standing orders, which had been in place since she had first become my apprentice. Bob had almost unlimited knowledge of magic. Molly had a calculated disregard for self-limitation when she thought it justified. They would have made a really scary pair, and I’d kept them carefully separate during her training.

“We need to get off the street,” I said. “Someplace quiet and secure.”

“I know a place just like that,” Molly said. “What happened?”

“Someone tossed a gym bag full of explosives at my car,” I growled. “And followed it up with the freaking pixie death squadron from hell.”

“You mean they picked this car out of all the other traffic?” she asked, her tone dry. “What are the odds?”

I grunted. “One more reason to get off the street, pronto.”

“Relax,” she said. “I started veiling the car as soon as we passed the police. If someone was following you before, they aren’t now. Catch your breath, Harry. We’ll be there soon.”

I blinked, impressed. Veils were not simple spells. Granted, they were sort of a specialty of Molly’s, but this was taking it up a notch. I didn’t know whether I could have covered the entire Caddy with a veil while driving alertly and carrying on a conversation. In fact, I was pretty sure I couldn’t.

Grasshopper was growing up on me.

I studied Molly’s profile while she drove. Stared, really. I’d first met her years ago, when she was a gawky little kid in a training bra. She’d grown up tall, five-ten or a little more. She had dark blond hair, although she had changed its color about fifty times since I’d met her. At the moment, it was in its natural shade and cut short, hanging in an even sheet to her chin. She was wearing minimal makeup. The girl was built like a particularly well-proportioned statue, but she wasn’t flaunting it in this outfit—khaki pants, a cream-colored shirt, and a chocolate brown jacket.

The last time I’d seen Molly, she’d been a starved-looking thing, dressed in rags and twitching at every sound and motion, like a feral cat—which was hardly surprising, given that she’d been fighting a covert war against a group called the Fomor while dodging the cops and the Wardens of the White Council. She was still lean and a little hyperalert, her eyes trying to watch the whole world at once, but that sense of overly coiled spring tension was much reduced.

She looked good. Noticing that made things stir under the surface, things that shouldn’t have been, and I abruptly looked away.

“Uh,” she said. “Harry?”

“You look better than the last time I saw you, kiddo,” I said.

She grinned, briefly. “Right back atcha.”

I snorted. “It’d be hard to look worse. For either of us, I guess.”

She glanced at me. “Yeah. I’m a lot better. I’m still not . . .” She shrugged. “I’m not exactly Little Miss Stability. At least, not yet. But I’m working on it.”

“Sometimes I think that’s where most of us are,” I said. “Fighting off the crazy as best we can. Trying to become something better than we were. It’s that second bit that’s important.”

She smiled, and didn’t say anything else. Within a few moments, she had turned the Caddy into a private parking lot.

“I don’t have any money for parking,” I said.

“Don’t need it.” She paused and rolled down the cracked window to wave at an attendant operating the gate. He glanced up from his book, smiled at her, and pushed a button. The gate opened, and Molly pulled the Caddy into the lot. She drove down the length of it, and pulled the car carefully into a covered parking spot. “Okay. Come on.”

We got out of the car, and Molly led me to a doorway leading into an adjacent apartment building. She opened the door with a key, but instead of moving to the elevators, she guided me to another doorway to one side of the entrance. She unlocked that one too, and went down two flights of stairs to a final door. I could sense magical defenses on the doors and the stairs without even making an effort to open myself up to it. That was a serious bunch of security spells. Molly opened the second door and said, “Please come in.” She smiled at Toot. “And your crew with you, of course.”

“Thanks,” I said, and followed her inside.

Molly had an apartment.

She had an apartment big enough for Hugh Hefner’s birthday party.

The living room was the size of a basketball court, and it had eleven-foot ceilings. There was a little bar separating the kitchen from the rest of the open space. She had a fireplace with what looked like a handmade living room set around it in one corner of the room, and a second section of comfy chairs and a desk tucked into a nook lined with built-in bookshelves. She had a weight bench, too, along with an elliptical machine, both of them expensive European setups. The floors were hardwood, broken up by occasional carpets that probably cost more than the floor space they covered. A couple of doors led off from the main room. They were oak. Granite countertops. A six-burner gas stove. Recessed lighting.

“Hell’s bells,” I said. “Uh. Nice place.”

Molly shrugged out of her jacket and tossed it onto the back of a couch. “You like?” She walked into the kitchen, opened a cabinet door, and pulled out a first-aid kit.

“I like,” I said. “Uh. How?”

“The svartalves built it for me,” she said.

Svartalves. They were some serious customers in the supernatural scene. Peerless artisans, a very private and independent folk—and they tolerated absolutely no nonsense. No one wants to get on the bad side of a svartalf. They weren’t exactly known for their generosity, either. “You working for them?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “This is mine. I bought it from them.”

I blinked again. “With what?”

“Honor,” she said. She muttered something and flicked a hand at a chandelier hanging over the table in the little dining area. It began to glow with a pure white light as bright as any collection of incandescent bulbs. “Bring him over here, and we’ll see if we can’t help him.”

I did so, transferring Toot from the skull to the table as gently as possible. Molly leaned down over him, peering. “Right through the breastplate? What hit you, Toot-toot?”

“A big fat jerk!” Toot replied, wincing. “He had a real sword, too. You know how hard it is to convince any of you big people to make us a sword we can actually use?”

“I saw his gear,” I said. “I totally liked yours better, Major General. Way cooler and more stylish than that stupid black-knight look.”

Toot gave me a brief, fierce grin. “Thank you, my lord!”

Toot got out of his ruined armor with effort, and with Molly’s cautious, steady-fingered help I managed to clean the wound and bandage it. It looked ugly, and Toot was anything but happy during the process, but he was clearly uncomfortable and weary, rather than being badly hurt. Once the wound was taken care of, Toot promptly flopped onto the table and went to sleep.

Molly smiled, got a clean towel out of a cabinet, and draped it over the little guy. Toot seized it and curled up beneath it with a sigh.

“All right,” Molly said, picking up the first-aid kit. She beckoned me to follow her to the kitchen. “Your turn. Off with the shirt.”

“Not until you buy me dinner,” I said.

For a second, she froze, and I wondered whether that had come out like the joke it had sounded like in my mind. Then she recovered. Molly arched her eyebrow in a look that was disturbingly like that of her mother (a woman around with whom a wise man will not mess) and folded her arms.

“Fine,” I said, rolling my eyes. I shrugged my way out of the ruined tux.

“Jesus,” Molly said softly, looking at me. She leaned around me, frowning at my back. “You look like a passion play.”

“Doesn’t feel so bad,” I said.

“It might if one of these cuts gets infected,” Molly said. “Just . . . just stand there and hold still. Man.” She went to the cabinet and came back with a big brown bottle of hydrogen peroxide and a couple of kitchen towels. I watched her walking back and forth. “We’ll start with your back. Lean on the counter.”

I did, resting my elbows on the granite, still watching her. Molly fumbled with the supplies for a second, then bit her lower lip and began to move with purpose. She started dribbling peroxide onto the cuts on my back in little bursts of cold liquid that might have made me jump before I’d spent so much time in Arctis Tor. It burned a little, and then fizzed enthusiastically.

“So, not one question?” I asked her.

“Hmmm?” She didn’t look up from her work.

“I come back from the dead, I sort of expected . . . I don’t know. A little shock. And about a million questions.”

“I knew you were alive,” Molly said.

“Yeah, I sort of figured. How?” She didn’t answer, and after a moment I realized the likely answer. “My godmother.”

“She takes her Yoda-ing seriously.”

“I remember,” I said, keeping my tone neutral. “How long have you known?”

“Several weeks,” Molly said. “There are so many cuts here, I don’t think I have enough Band-Aids. We’ll have to wrap it, I guess.”

“I’ll just put a clean shirt over them,” I said. “Look, it isn’t a big deal. Little marks like that are going to be gone in a day or two.”

“Little . . . Winter Knight stuff?”

“Pretty much,” I said. “Mab . . . kinda gave me the tour during my recovery.”

“What happened?” she asked.

I found my eyes wandering to Bob’s skull. Telling Molly what was going on would mean that she was involved. It would draw her into the conflict. I didn’t want to expose her to that kind of danger—not again.

Of course, it probably wasn’t my sole decision. And besides, Molly had intervened in an assassination that had been really close to succeeding. Whoever was behind the swarm of piranha pixies had probably seen it. Molly was already in the fight. If I started keeping things from her now, it would only hinder her chances of surviving it.

I didn’t want her involved, but she’d earned the right to make that choice for herself.

So I gave it to her, straight, succinct, and with zero editing except for the bit about Halloween. It felt sort of strange. I hardly ever tell anyone that much truth. The truth is dangerous. She listened, her large eyes steadily focused on a point around my chin.

When I finished, all she said was, “Turn around.”

I did, and she started working on the cuts on my chest, arms, and face. Again, cleaning the wounds was a little uncomfortable, but nothing more. I watched her tending me. I couldn’t read her expression. She didn’t look up at my eyes while she worked, and she kept her manner brisk and steady, very businesslike.

“Molly,” I said, as she finished.

She paused, still not looking up at me.

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry that I had to ask you to help me . . . do what I did. I’m sorry that I didn’t make you stay home from Chichén Itzá. I never should have exposed you to that. You weren’t ready.”

“No kidding,” Molly said quietly. “But . . . I wasn’t really taking no for an answer at the time, either. Neither of us made smart choices that night.”

“Maybe. But only one of us is the mentor,” I said. “I’m supposed to be the one who knows what’s going on.”

Molly shook her head several times, a jerky motion. “Harry—it’s over. Okay? It’s done. It’s the past. Let it stay there.”

“Sure you want that?”

“I am.”

“Okay.” I picked up a paper towel and dabbed at a few runnels of peroxide bubbling their way down my stomach. “Well. Now all I need is a clean shirt.”

Molly pointed at one of the oak doors. “In there. There are two dressers and a closet. Nothing fancy, but I’m pretty sure it will all fit you.”

I blinked several times. “Um. What?”

She snorted and rolled her eyes. “Harry . . . duh. I knew you were alive. That meant you’d be coming back. Lea told me to keep it to myself, so I got a place ready for you.” She took a quick step back into the kitchen, opened a drawer, and came back with a small brass key. “Here, this will get you past the locks, and past the svartalves’ wards and past my defenses.”

I took the key, frowning. “Um . . .”

“I’m not asking you to shack up with me, Harry,” Molly said, her tone dry. “It’s just . . . until you get back on your feet. Or . . . or just as long as you’re in town and need a place to stay.”

“Did you think I couldn’t take care of it myself?”

“Of course not,” Molly said. “But . . . you know. I guess I think that maybe you shouldn’t have to?” She looked up at me uncertainly. “You were there when I needed you. I figured it was my turn now.”

I looked away before I got all emotional. The kid had gotten this place together, made some kind of alliance with a very suspicious and cautious supernatural nation, furnished a room for me, and picked me up a wardrobe? In just a few weeks? When she’d been living in rags on the street all the time for the better part of a year before that?

“I’m impressed, grasshopper,” I said. “Seriously.”

“This isn’t the impressive part,” she said. “But I don’t think we have time to get into that right now, given what you’ve got going.”

“Let’s survive Halloween,” I said, “and then maybe we can sit and have a nice talk. Molly, you shouldn’t have done this for me.”

“Ego much?” she asked, the ghost of her old, irreverent self lurking in her eyes. “I got this place for me, Harry. I lived my whole life in one home. Living on the street wasn’t . . . wasn’t a good place for me to put myself back together. I needed someplace . . . someplace . . .” She frowned.

“Yours?” I suggested.

“Stable,” she said. “Quiet. And mine. Not that you aren’t welcome here. While you need it.”

“I suppose you didn’t get those clothes for my sake, either.”

“Maybe I started dating basketball teams,” Molly said, her eyes actually sparkling for a moment. “You don’t know.”

“Sure I do,” I said.

She started putting the kit away. “Think of the clothes as . . . as a birthday present.” She looked up at me for a second and gave me a hesitant smile. “It’s really good to see you, Harry. Happy birthday.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I’d give you a hug, but I’d bleach and bloodstain your clothes at the same time.”

“Rain check,” Molly said. “I’m, uh . . . Working up to hugs might take a while.” She took a deep breath. “Harry, I know you’ve got your hands full already, but there’s something you need to know.”

I frowned. “Yeah?”

“Yeah.” She rubbed her arms with her hands as though cold. “I’ve kind of been visiting your island.”

In the middle of the southern reaches of Lake Michigan lies an island that doesn’t appear on any charts, maps, or satellite images. It’s a nexus point of ley lines of dark energy, and it doesn’t like company. It encourages people who come near it to get lost and wander away. Planes fly over the thing all the time, but no one sees it. A few years back, I’d bound myself to the island, and the world-class genius loci that watched over it. I’d named it Demonreach, and knew relatively little about it, beyond that it was an ally.

When I’d been shot and plunged into the dark waters of Lake Michigan, it had taken Mab and Demonreach both to preserve my life. I’d woken up from a coma in a cavern beneath the island’s surface with plants growing into my freaking veins like some kind of organic IV line. It was a seriously weird kind of place.

“How did you get there?” I asked.

“In a boat. Duh.”

I gave her a look. “You know what I mean.”

She smiled, the expression a little sad. “After you’ve had someone like the Corpsetaker pound your mind into pomegranate seeds, a psychic No Trespassing sign seems kinda slow-pitch.”

“Heh,” I said. “Point. But it’s a dangerous place, Molly.”

“And it’s getting worse,” she said.

I shifted my weight uneasily. “Define ‘worse.’”

“Energy is building up there. Like . . . like steam in a boiler. I know I’m still new at this—but I’ve talked with Lea about it and she agrees.”

God, she was dragging this out, making me wonder what she knew. I hate that. “Agrees with what?”

“Um,” Molly said, looking down. “Harry. I think that within the next few days, the island is going to explode. And I think that when it does, it will take about half the Midwest with it.”

Chapter

Fourteen

“Of course it is,” I said. I looked around and grabbed the first-aid kit, then started stomping toward the indicated guest bedroom. “I swear, this stupid town. Why does every hideous supernatural thing that happens happen here? I’m gone for a few months and augh. Be right back. Grrssll frrrsl rassle mrrrfl.”

There was a light switch in the bedroom and it worked. The lightbulb stayed on and everything. I scowled up at it suspiciously. Normally when I’m in a snit like this, lightbulbs don’t survive eye contact, much less my Yosemite Sam impersonation. Evidently, the svartalves had worked out a fix for technological grumpy-wizard syndrome.

And the room . . . well.

It reminded me of home.

My apartment had been tiny. You could have fit it into Molly’s main room half a dozen times, easy. My old place was almost the same size as her guest bedroom. She’d furnished it with secondhand furniture, like my place had been. There was a small fireplace, with a couple of easy chairs and a comfortable-looking couch. There were scuffed-up old bookshelves, cheap and sturdy, lining the walls, and they contained what was probably meant to be the beginning of a replacement for my old paperback fiction library. Over toward where my bedroom used to be was a bed, though it was a full rather than a twin. A counter stood where my kitchen counter had been, more or less, and there was a small fridge and what looked like an electric griddle on it.

I looked around. It wasn’t home, but . . . it was in the right zip code. And it was maybe the single sweetest thing anyone had ever done for me.

For just a second, I remembered the scent of my old apartment, wood smoke and pine cleaner and a little bit of musty dampness that was inevitable in a basement, and if I squinted my eyes up really tight, I could almost pretend I was there again. That I was home.

But they’d burned down my home. I had repaid them for it, with interest, but I still felt oddly hollow in my guts when I thought about how I would never see it again. I missed Mister, my cat. I missed my dog. I missed the familiarity of having a place that I knew, that was a shelter. I missed my life.

I’d been away from home for what felt like a very long time.

There was a closet by the bed, with a narrow dresser on two sides. It was full of clothes. Nothing fancy. T-shirts. Old jeans. Some new underwear and socks, still in their plastic packaging. Some shorts, some sweatpants. Several pairs of used sneakers the size of small canoes, and some hiking boots that were a tolerable fit. I went for the boots. My feet are not for the faint of sole, ah, ha, ha.

I ditched the tux, cleaned up and covered the injuries on my legs, and got dressed in clothes that felt familiar and comfortable for the first time since I’d taken a bullet in the chest.

I came out of the bedroom holding the bloodied clothes, and glanced at Molly. She pointed a finger at the fire. I nodded my thanks, remembered to take the bejeweled cuff links out of the pockets of the pants, and tossed what was left into the fire. Blood that had already been soaked up by cloth wouldn’t be easy to use against me, even if someone had broken in and taken it somehow, but it’s one of those things best not left to chance.

“Okay,” I said, settling down on the arm of a chair. “The island. Who else knows about it?”

“Lea,” Molly said. “Presumably she told Mab. I assumed word would get to you.”

“Mab,” I said, “is apparently the sort of mom who thinks you need to find things out for yourself.”

“Those are real?”

I grunted. “Have you had any contact with Demonreach?”

“The spirit itself?” Molly shook her head. “It . . . tolerates my presence, but it isn’t anything like cordial or friendly. I think it knows I’m connected to you.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I’m sure it does. If it wanted you off the island, you’d be gone.” I shook my head several times. “Let me think.”

Molly did. She went into the kitchen, to the fridge. She came out with a couple of cans of Coca-Cola, popped them both open, and handed me one. We tapped the cans together gently and drank. I closed my eyes and tried to order my thoughts. Molly waited.

“Okay,” I said. “Who else knows?”

“No one,” she said.

“You didn’t tell the Council?”

Molly grimaced at the mention of the White Council of Wizards. “How would I do that, exactly? Given that according to them, I’m a wanted fugitive, and that no one there would blink twice if I was executed on sight.”

“Plenty of them would blink twice,” I said quietly. “Why do you think you’re still walking around?”

Molly frowned and eyed me. “What do you mean?”

“I mean that Lea’s clearly taught you a lot, Molly, and it’s obvious that your skills have matured a lot in the past year. But there are people there with decades’ worth of years like the one you’ve had. Maybe even centuries. If they really wanted you found and dead, you’d be found and dead. Period.”

“Then how come I’m not?” Molly asked.

“Because there are people on the Council who wouldn’t like it,” I said. “My g– Ebenezar can take anyone else on the Council on any given day, if he gets mad at them. That’s probably enough—but Ramirez likes you, too. And since he’d be the guy who would, theoretically, be in charge of capturing you, anyone else who did it would be walking all over his turf. He’s young, too, but he’s earned respect. And most of the young guns in the Wardens would probably side with him in an argument.” I sighed. “Look, the White Council has always been a gigantic mound of assorted jerks. But they’re not inhuman.”

“Except sometimes,” Molly said, her voice bitter.

“Humanity matters,” I said. “You’re still here, aren’t you?”

“No thanks to them,” she said.

“If they hadn’t shown up at Chichén Itzá, none of us would have made it out.”

Molly frowned at that. “That wasn’t the White Council.”

True, technically. That had been the Grey Council. But since the Grey Council was mostly made up of members of the White Council working together in secret, it still counted, in my mind. Sort of.

“Those guys,” I said, “are what the Council should be. And might be. And when we needed help the most, they were there.” I sipped some more Coke. “I know the world seems dark and ugly sometimes. But there are still good things in it. And good people. And some of them are on the Council. They haven’t been in contact with you because they can’t be—but believe me, they’ve been shielding you from getting in even more trouble than you’ve already had.”

“You assume,” she said stubbornly.

I sighed. “Kid, you’re going to be dealing with the Council your whole life. And that could be for three or four hundred years. I’m not saying you shouldn’t get in their faces when they’re in the wrong. But you might want to consider the idea that burning your bridges behind you could prove to be a very bad policy a century or two from now.”

Molly looked like she wanted to disagree with me—but she looked pensive, too. She drank some more of her Coke, frowning.

Damn. Why couldn’t I have figured out that particular piece of advice to give to myself when I was her age? It might have made my life a whole lot simpler.

“Back to the island,” I said. “How sure are you about the level of energy involved?”

She considered her answer. “I was at Chichén Itzá,” she said. “It’s all pretty blurry, but I remember a lot of fragments really well. One of the things I remember is the tension that had built up under the main ziggurat. Do you remember?”

I did, though it had been pretty far down on my list of priorities at the time. The Red King had ordered dozens, maybe hundreds of human sacrifices to build up a charge for the spell he was going to use to wipe me and everyone connected to me by blood from the face of the earth. That energy had been humming inside the very stones of the city. Go to a large power station sometime, and stand near the capacitors. The air is full of the same kind of silently vibrating potential.

“I remember,” I said.

“It’s like that. Maybe more. Maybe less. But it’s really, really big. It’s scaring the animals away.”

“What time is it?” I asked.

Molly checked a tall old grandfather clock, ticking steadily away in a corner. “Three fifteen.”

“Ten minutes to the marina. An hour and change to the island and back. Call it an hour for a service call.” I shook my head and snorted. “If we leave right now, that puts us back here in town right around sunrise, wouldn’t you say?”

“More or less,” she agreed.

“Mab,” I said, in the same tone I reserved for curse words.

“What?”

“That’s why the lockdown,” I said. Then clarified. “Mab closed the border with Faerie until dawn.”

Molly was no dummy. I could see the wheels turning as she figured it out. “She’s giving you time to deal with it unmolested.”

“Relatively unmolested,” I corrected her. “I’m starting to think that Mab mainly helps those who help themselves. Okay. Once Maeve gets to start moving pieces in and out of Faerie in the morning, things are going to get busy, fast. Also, I don’t want to be working with the magical equivalent of a reactor core the next time Hook and his band of minipsychos catch up with me. So.”

Molly nodded. “So we go to the island first?”

“We go to the island now.”

* * *

Molly had the apartment building’s security call us a cab on the theory that it would be slightly less noticeable than the monster car now in the parking lot. They took her orders as if she were some kind of visiting dignitary. Whatever she’d done for the svartalves, they had taken it very, very seriously. I left Toot sleeping off the fight, with some junk food left out where he would find it when he woke up. Bob was in a cloth messenger bag I had slung over one shoulder, still buttoned up tight. Molly glanced at the bag, then at me, but she didn’t ask any questions.

I felt like wincing. Molly hadn’t ever exactly been shy about pushing the boundaries of my authority in our relationship as teacher and apprentice. Her time with my faerie godmother, the Leanansidhe, Mab’s girl Friday, was starting to show. Lea had firm and unyielding opinions about boundaries. People who pushed them got turned into dogs—or something dogs ate.

The marina was one of several in the city. Lake Michigan provided an ideal venue for all kinds of boating, sailing, and shipping, and there was a nautical community firmly established all around the shores of the Great Lake. I’m not really part of it. I say “wall” instead of “bulkhead,” and I’m not quite sure if port is left, or if it’s something best left until after dinner. I get the terms wrong a lot. I don’t care.

Marinas are parking lots for boats. Lots of walkways were built on piers or were floating pontoon bridge–style in long, straight rows. Boats were parked in individual lots much like in any automobile parking lot. Most of the boats showed signs of being prepared for winter—November can be a dangerous time for pleasure boating on Lake Michigan, and most people pack it in right around Halloween. Windows and hatches were covered, doors closed, and there were very few lights on in the marina.

Which was good, because I was breaking and entering again.

I’d had a key to the marina’s locks at one time, but I’d lost track of it when I got shot, drowned, died, got revived into a coma, haunted my friends for a while, and then woke up in Mab’s bed.

(My life. Hell’s bells.)

Anyway, I didn’t have a key or any time to spare, so when I got to the locked gate to the marina, I abused my cool new superstrength and forced the chain-link gate open in a low squeal of bending metal. It took me about three seconds.