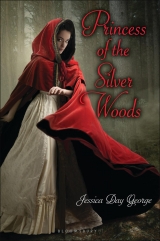

Текст книги "Princess of the Silver Woods"

Автор книги: Jessica Day George

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

“How will I know … how will you find me if you, if the king …” He couldn’t even finish the sentence.

Heinrich, whose thoughts had clearly been miles away, focused sharply on Oliver again. “Do you remember where the royal coach crashed? That bank, where the road curves?”

“Yes,” Oliver said, wondering if he would ever not remember the place where he had watched, sick, to see whether Petunia had been hurt. And where, just through the trees, he had kidnapped her.

“We’ll leave a message there.” Heinrich’s smile turned into a grimace again. “It would help if you did not rob any more coaches.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Oliver said, thinking about what stores they had and how much they had taken on their last raid. “But I have people who need to eat.”

“I understand,” Heinrich said. “We’ll work as quickly as we can to help you.”

“Thank you,” Oliver said. He fastened the cloak, then he stopped again. “But first … make sure Petunia and her sisters are safe.”

“Don’t worry,” Heinrich said. “We will.”

Oliver climbed down the ivy to freedom.

Youngest

Petunia embarrassed herself by bursting into tears when her sisters arrived.

Rose swept Petunia into her arms and held her tightly, and the others crowded in to hug or pat what part of her they could reach, even Poppy. When Rose set Petunia back on her feet and offered her a handkerchief, Petunia looked at Lily’s pale, haggard face, and burst into tears all over again.

“Lilykins, what will we do?” Petunia sobbed. “It’s happening all over again!”

Lily nodded soberly, opening her mouth to speak, but was interrupted.

“Now, now, my beautiful princesses,” cried the grand duchess. “Into the parlor with you! You are tired from your journey, and dear Petunia has not had the rest that she needs, she has pined so for you. So first a nice cold supper in the parlor, and then early to bed, or there will only be more tears tomorrow!”

The grand dame spread her lace-gowned arms wide and ushered them all into the parlor while anxious maids tried to get the last of the cloaks, gloves, and muffs from the princesses before they entered. Petunia let the crowd of familiar faces and gowns carry her into the parlor and took the place of honor on the sofa between Rose and Lily without a murmur.

She had not returned to the Kingdom Under Stone in her sleep for three nights, not since Rionin had declared his intention to marry Lily. But now her sleep was even more restless, plagued with nightmares not sent by the King Under Stone, but by her own mind: nightmares of being trapped in the sunless kingdom forever, of fox-faced men laughing and taunting her, of marrying Kestilan in some arcane ceremony.

When the courier had arrived the next day, to announce that all the princesses would be coming to visit their sister, Petunia had nearly collapsed with relief. She had been begging the grand duchess to let her go home, but the older woman was convinced that Petunia’s nighttime hysteria was a symptom of impending illness and would not let her travel.

But the sisters needed to talk. Rionin was proving to be as great a threat as his father had been, and it would only be a matter of time until a new gateway was created and they were pulled once more into the Kingdom Under Stone.

As the footmen laid out trays of tiny sandwiches, hothouse fruits, cheeses, and pastries on the side tables, Petunia looked around at her sisters. They were all uniformly pale and tired, much as they had been when they had actually danced at the Midnight Balls. Jonquil looked especially ill. Petunia had thought (rather uncharitably) that Jonquil would have perked up when she found that Rionin didn’t want her anymore, but that did not seem to be the case. Her hands shook as she accepted a cup of tea from a young footman, who seemed concerned that Jonquil would spill it down the skirts of her fine golden wool carriage dress.

“Is Jonquil still—” Petunia started to say to Rose in a low voice, but Rose shook her head. Her eyes went to the grand duchess, seated in her usual high-backed chair with its many small pillows to cushion the elderly woman’s back.

“You all look so worn out, my dears,” said the grand duchess, whose ears had not been dimmed by her age, something Petunia always forgot. “Is it the preparations for the double wedding that keep you so busy?” She smiled at Poppy and Daisy.

“I wish,” muttered Poppy.

At the same time, from her seat on a pouf in front of Petunia’s, Iris said, “Yes, but it’s the wrong royal wedding.” Lily gave her a light poke between the shoulder blades before she could say anything else.

“How is that, my dear Iris?”

The grand duchess had remembered their names instantly upon meeting them, which impressed Petunia. She’d spent years being called Pansy or Poppy, sometimes even by her own father. And most people seemed to have trouble telling Orchid and Iris apart, despite Orchid’s wearing spectacles.

“I just … it was nothing,” Iris said, and from behind her, Petunia could see her ears turn pink.

“I think that perhaps Iris is a touch jealous,” Rose said in a confidential voice, leaning over the arm of the sofa a bit, as though sharing a secret with the grand duchess. “She is only a year younger than the twins, you know.”

“I’m not—” began Iris, but both Petunia and Lily poked her and she subsided.

“It has been most trying,” Poppy said in a posh voice that Petunia suspected was modeled after that of Lady Margaret, their mother’s cousin, a famous Bretoner society lady with whom Poppy had lived for a year. “One wedding takes quite enough planning, but two?” She threw up her hands dramatically.

Petunia had to admire Poppy’s skill at deflecting the grand duchess. Poppy, who as a child had been known for her sharp tongue and hoydenish ways, had been greatly improved by her time in Breton. Yet Petunia often got the impression that Poppy was merely playing a part, impersonating Lady Margaret, and was relieved that Poppy’s personality had not gone through a permanent transformation. She could tell that Prince Christian loved Poppy just as she was, too.

“A difficult task, indeed,” the grand duchess agreed. “I recall my own wedding, so many years ago. Russaka has always held itself aloof from the rest of Ionia, and our customs are very different. I thought my betrothed’s mother would faint from shock when she saw my wedding headdress and heard the mandolins and flutes playing instead of the church organ.”

“Did you marry here in Westfalin?” Pansy looked dreamy at the thought. If anyone was feeling a bit jealous of the twins’ upcoming marriages, reflected Petunia, it was probably Pan.

“Yes,” the grand duchess said, nodding. “My betrothed was already an earl, and I was only one of nine daughters. It was easier to send me here with my mother and two of my sisters as attendants than to bring every Westfalian noble who wished to attend to Russaka!” She laughed at the memory.

Pansy looked as though she was going to press for more details, but Hyacinth, seated on the chair just beside Petunia’s sofa, spoke up first.

“Nine daughters?” Her eyes were narrowed.

“Yes, it was considered a lot, until your mother went three further than mine!” The old lady cackled good-naturedly.

Hyacinth muttered under her breath, “I wonder who her mother bargained with to get nine daughters.”

“My mother didn’t make any bargains,” the grand duchess said coolly, and Hyacinth looked nonplussed at being heard.

Petunia wondered if any of her sisters caught the emphasis on the word “mother.” Did she, then, know someone who had made a bargain with a supernatural being? Who? The grand duchess herself? If she had in fact borne a son to the King Under Stone … no, Petunia couldn’t even think it of her.

“Now, we must get you rested before your husbands join us tomorrow!” The grand duchess got to her feet, moving to the door of the parlor. “Though I find it most strange that none of them came with you,” she added.

“Galen and Heinrich had business in Bruch,” Rose said. There was a small line between her brows, and Petunia wondered just what the cousins were doing. “And Poppy and Daisy’s husbands-to-be had to return to the Danelaw and Venenzia to make their own preparations for the wedding.”

“But lucky Violet’s husband is coming tomorrow,” Daisy said.

“Ah, the Archduke von Schwabian’s son,” the grand duchess said, and Petunia thought she detected a slight curl to the older woman’s lip. “The musical one.”

“He’s picking up a new cello from the luthier,” Violet said, as though it was a matter of grave political importance.

“And yours? Where is your husband?” The grand duchess looked at Hyacinth.

“He’s going to Venenzia with Ricard, actually,” Hyacinth said, a blush staining her cheeks. “He wished to consult with a physician there.”

They were all poised to follow the grand duchess into the hall, but she stood unmoving in the doorway. “None of you have children, correct?” The question was shockingly blunt.

Lily swayed and Lilac put her arm around her older sister. Petunia glanced up at Rose and saw Rose’s jaw clench. Someone gave a little gasp, and Petunia looked at Hyacinth, but Hyacinth’s expression was cool, her blush gone. It was Orchid whose mouth was open in shock, her eyes flashing behind her spectacles.

“No,” Rose said finally. “None of the four of us who are married have children.” Her voice was steady, but deeper than normal.

“What a shame,” the grand duchess said. “It’s children that really tie a man and woman together.”

“If I may be shown to my room,” Lily said. “This has all quite worn me out.”

“And I as well,” Jonquil said, moving to stand beside Lily. The two of them together looked like they might simply break in half if a strong draft blew through the room.

“Of course,” said the grand duchess. “Come into the front hall, and I’ll have the maids show you up. I’m afraid that the stairs have become too much for me.” The grand duchess’s private apartments were on the main floor overlooking the gardens. In fact, they were directly below Petunia’s room, and Petunia wondered if she’d seen Kestilan and his shadowy brethren coming across the lawns at night.

After the sisters had been shown to their rooms and thanked the maids for working so swiftly to unpack the princesses’ luggage, they all gathered in Rose’s sitting room. The maids tried to crowd in as well, but Rose sent them off with a few firm words and a quick close of the door.

“What’s happening?” Petunia asked as soon as she was sure the maids were out of earshot.

“Galen and Heinrich are setting your young man free,” Rose said. “That’s why they won’t be joining us until tomorrow. They wanted to make sure that we were out of the way, and so was Father. Dr. Kelling is taking him to the fortress for a few days, to clear his head.”

“My young man? Setting him free?” Petunia stared at her. “I have no idea what you’re talking about, Rosie. What young man?”

“The handsome bandit earl,” Poppy supplied.

Petunia felt her mouth slip open. “Oliver?”

“Yes,” Rose said, and gave Poppy a quelling look before she could say anything else. “He came to Bruch last week and confessed to leading the bandits, and to abducting you.”

“He did? Why would he do that?”

Petunia felt like the floor had just dropped out from under her feet. She sank down onto the very edge of a sofa, and Lilac, grumbling, made room for her. Having the leader of the Wolves of the Westfalian Woods turn himself in after all attempts to capture him had failed was likely to have put her father in a very dangerous mood.

Especially if the bandit also confessed to kidnapping one of his daughters.

Petunia could picture Oliver in the Bruch jail … well, what her imagination conjured for the Bruch jail, anyway. She imagined a small, dank cell with a barred door, and Oliver sitting forlorn in one corner with a rat by his feet and his curly hair lank over his smudged forehead. What purpose could turning himself in serve? She knew that he hated banditry, but his people still depended on him!

Shaking herself, Petunia looked around. Several of her sisters had been talking to her, but she hadn’t heard them.

“And that answers our questions about why he gave himself up,” Poppy was saying, a smile turning up one corner of her mouth as she looked at Petunia. “Now if everyone could please avoid saying his name, so that Petunia doesn’t drift off again … ?”

“I didn’t drift off,” Petunia said hotly. “I was just wondering what would make him throw it all away.…”

“Throw all what away?” Poppy asked. “He made it sound like he’d been living in squalor out in the forest, despite all the gold he’s stolen.”

“He doesn’t keep it,” Petunia said, defensive. “There are people who depend on him. They use the gold to buy food.”

“That’s what bothers me,” Lily said, before Poppy could think of a retort. “If he has so many people depending on him, why didn’t he tell Papa before?”

“Didn’t he explain?” Petunia was eager to defend Oliver, despite Poppy’s teasing. “His mother brought him to court to try to have his estate returned to him.” She pointed at the floor. “This estate. It’s the center of his earldom. But after the war, half of the earldom was in Analousia, and the other half was given to the grand duchess’s husband.” She lowered her voice on the last part. “But when they got to Bruch, we were being accused of witchcraft, and Anne was imprisoned for supposedly teaching it to us. Oliver’s mother is Bretoner, and she was afraid that she would be accused too.”

“That’s what he told Father and the ministers,” Rose said, nodding.

“But it’s just silly,” Orchid protested. “Why would they think she was a witch just because she was Bretoner? Papa isn’t completely unreasonable!”

“But Bishop Angiers was,” Petunia said. “And he was the one doing the accusing. I remember that horrible man trying to question me, as though I were a murderer.” She shuddered.

“Oliver’s mother, Lady Emily, was one of Mama’s closest friends,” Rose said. “I remember her, though the rest of you are probably too young. Anyone who knew Mama would have recognized Lady Emily.”

“She was there when Mama thought she couldn’t have any children?” Poppy asked.

“And when she suddenly started to have us, one after the other,” Rose said with a nod. “Witchcraft.”

“I still say that’s a silly way to think,” Orchid protested, but they ignored her.

“I wonder,” Daisy said slowly. “I wonder if Lady Emily wasn’t already scared because their estate had been given away. That would certainly make me wonder if the king was angry with me. And when they arrived in Bruch, she heard the rumors and thought that she had already been accused, and that was why the earldom had been divided up?”

“Oh, pooh!” Lilac fluttered her hand. “Like Petunia said, Papa wasn’t the one doing the accusing! I agree with Orchid: this whole thing seems very odd.”

“Indeed it is,” Rose said. “More than odd. Galen and I are certain that there was witchcraft involved—but it wasn’t Lady Emily who was responsible.”

“Then who is responsible?” Petunia asked.

“We don’t know yet, although now that we know the grand duchess is one of the Nine Daughters,” Rose began, but Petunia interrupted her.

“The grand duchess couldn’t possibly be a witch! You’ll never meet a more respectable lady!”

“At any rate,” Rose said, “something is highly suspicious about Oliver’s situation. Once we’ve … taken care of … our own problem with the King Under Stone and his brothers, Galen has promised to sort out Oliver’s missing earldom.”

“That’s wonderful,” Petunia said.

“If it works,” Lilac said ominously, and then, at the expression on Petunia’s face, she took out her knitting and fiddled with the needles.

“It will be well,” Rose said firmly. “Galen and Heinrich took care of it; that’s why they aren’t joining us until tomorrow.”

“What did they take care of?” Petunia felt faint, and the question was barely a whisper.

“They let Oliver go,” Rose said complacently. She took out her own knitting. “And the men that came with him to confess.”

“It was Heinrich’s idea,” Lily said with pride. “Papa was determined to execute the poor boy at the end of the week! But the old earl, Oliver’s father, was Heinrich’s commander in the Eagle Regiment. He saved Heinrich’s life, twice, and Heinrich said he couldn’t possibly let his son die. Dr. Kelling had already convinced father to go to the fortress for a few days, to take some time to think. Once they left, Galen was going to set Oliver’s men free while Heinrich helped Oliver escape.”

“Do you think they succeeded?” Pansy’s hands were twisted together.

But Petunia didn’t doubt it. She felt as if a great weight had been lifted from her chest. Galen and Heinrich had set Oliver and his men free. They could return to the forest and hide. They would be all right—he would be all right!

“If Galen can defeat the King Under Stone, I’m sure he can let a few prisoners out of the Bruch jail,” Poppy said staunchly, and Rose smiled at her.

“But Galen didn’t defeat the King Under Stone,” Hyacinth said, gazing out the window at the barren winter gardens. “Not yet, anyway.”

Worried

When Oliver and his men walked through the gates of the old hall, everyone within froze. Sentries had seen them, of course, and sounded no alarm, since there was no sign of any Westfalian soldiers. But they did not have the look of men returning triumphant, either. A few of the children sent up a ragged cheer, but their mothers quickly hurried them away, as though they knew that Oliver’s news was nothing to celebrate.

“What happened?” Simon couldn’t wait for Oliver to start talking. He leaned forward on his crutches, his face eager. “Did you see the king? Will he make you a real earl?”

“We went to Bruch,” Oliver said, and to his own ears his voice sounded ten years older. Lady Emily put a hand on her younger son’s arm. “And we saw the king.”

“What did the king do?” Lady Emily asked gently, when Oliver did not continue.

“I was put in the palace attic,” Oliver said, “and the others were put in the city jail.”

Karl’s wife, Ilsa, who had followed them into the old hall, clucked a bit at this, but Karl put a comforting arm around her.

“The room was small, and the windows were barred, but we had clean bedding and there was plenty of food to eat,” he said. “Not that it was as good as yours,” he added.

“I was in much the same situation,” Oliver told his mother and brother. “A small room, but clean, good food. I even had books to read. I told the king everything—about Father, about us. I told him about meeting Petunia, and … accidentally abducting her. He brought in one of his sons-in-law, Heinrich, who had been in Father’s regiment. He confirmed that Father had died, that he had had a son, and that I looked like him,” Oliver finished.

“And then what did you do, Lord Oliver?” Karl’s eight-year-old daughter gazed up at him in awe, as though this were the best story she had ever heard.

“And then I went back to my room,” Oliver said, wishing he had a better story to tell her. “Two of the princesses came to see me, and I told them everything as well. One of them brought me two books she thought would interest me. I read them, trying to find out why. Both of them had stories of the King Under Stone in them.” He looked at his mother. “One talked of the King Under Stone being the father of the sons of the Nine Daughters of Russaka,” he said meaningfully. “And other children.”

“What does that have to do with us?” Simon’s face was screwed up with confusion.

The men, who had not heard this part before, also looked confused, but Oliver ignored them for the moment. He could see that his mother was starting to understand some of the implications in the King Under Stone having a whole pack of strange half-human sons, and what it might mean for the beautiful daughters of King Gregor.

“But then Prince Heinrich came to my room.” Oliver reached under his jacket and pulled out the dull purple cape he had stuffed there for safekeeping. “Wearing this. It makes you invisible.” Karl’s daughter clapped her hands in delight, and Simon looked like he would have done the same if not for his crutches. “King Gregor had decided to execute us.” This did not make Karl’s daughter clap. “But Heinrich owed Father his life. He claims that once the king has had time to think, he will go easier on us. He and Crown Prince Galen will argue with the king on our behalf.”

“It was the crown prince himself who set us free,” Johan said. “He marched right into the jail, and all the guards went to sleep like new lambs. He opened our cell, told us where to meet young Oliver, and then saw us out the door like we had been guests in his home.”

“So, it’s good news,” Ilsa said doubtfully.

“We’re wanted men,” Karl told her.

“You have been for years,” she scoffed.

“But now we’re wanted men who’ve escaped jail,” Karl clarified. “And who are to wait and see if two princes can argue their father-in-law to amnesty.”

“Princes can be rather flighty,” Ilsa said sagely. She had been born and raised in the forest, and Oliver’s parents were the closest she had ever come to nobility, let alone royalty.

“So, now what?” Simon looked disgusted. “We all just sit here and wait to see if the king forgives you?”

“More or less,” Oliver said. “They’ll send someone with the new verdict to the place where Petunia’s coach got smashed.” He turned to Karl. “We’ll have to keep a watch on it. But not for a few days. The king is hunting, and the princes will be at the grand duchess’s estate with their wives.”

Karl grunted. “We watch that spot anyway,” he said with a shrug. “It’s not far from where we wait for likely coaches.”

Oliver shook his head. “Just have the sentries watch that one spot. We won’t need to know about any other coaches.”

“What do you mean?” Simon looked from Oliver to Karl. “Did they give you money?”

“Think, Simon,” Oliver said. “We’re trying to convince the king to forgive us for robbing all those coaches for all those years. In order to show him that we’re penitent, we need to stop robbing coaches.”

“But what will we live on?” Simon wanted to know.

Oliver rubbed his face, wondering if he had lines etched at the corners of his mouth the way Johan did. He felt like it. He felt like he was a hundred years old. He took a breath and let it out.

“Well, you tell me,” he said to his little brother. “Haven’t you begun taking over the steward’s duties? What have we got? How long will it last?”

Simon thought for a moment. “We’ve got potatoes,” he said. “Lots of dried things. You’ll still let us poach game, I hope? And there’s some money in the strongbox.…”

“We’ll be fine,” Lady Emily said.

And abruptly Oliver was done. He was tired. He wanted to lie in his own bed, in his own room, and never come back out. He spun on his heel and made his way up the creaking staircase, not looking back at the circle of faces below, watching him.

When he got to the top of the stairs, however, Karl’s little daughter called out, “Nighty-night, Earl Oliver!”

He leaned over the banister and waved to the child, not meeting her or anyone else’s eyes, and then went into his room and shut the door.

Fingering the invisibility cloak, Oliver sat down on his bed. Then he lay down, boots and all, and went to sleep. When he woke up it was dark in the room except for a single lamp near the one chair. His mother was sitting in the chair, darning a stocking.

“Are you ready to talk?” Lady Emily asked as he blinked at her.

“I hate the king,” Oliver said. It surprised him.

It did not, however, appear to surprise his mother.

“He changed when Maude died,” she said. She bit off the thread and rolled up the stocking, putting it in her sewing basket and taking out another. “But then, you’ve always hated Gregor.”

“I didn’t meet him until four days ago,” Oliver protested weakly.

“Don’t think that I don’t know why you and your men have gone after every coach with a crest on the doors,” she said in a reproving voice. “It was only a matter of time until you robbed one of the princesses, or Gregor himself. You’ve been trying to get the king’s attention.”

“And now I’ve succeeded,” Oliver said bitterly. “And I didn’t even have to let that fool of a Russakan prince hunt me down.”

“For which I will always be grateful,” Lady Emily said.

The real fervor in her voice made Oliver look at her more carefully. The golden lamplight couldn’t hide her pallor or the strain around her eyes.

“I don’t like the sound of this Prince Grigori,” she said, and Oliver nearly laughed. “And if the King Under Stone is the father of the Nine Daughters’s children, then Prince Grigori is the nephew of Under Stone’s sons.”

“Which means what for us?” Oliver asked.

He shifted uneasily on the bed, sitting up and fussing with the pillow behind his back. Oliver pictured Grigori roaring through the forest on his black horse, sitting impossibly tall, dark-haired, white-skinned—he didn’t look human. But he was, wasn’t he?

“I don’t know what it means,” Lady Emily said, “except that we must be cautious.”

“I am,” Oliver began.

“You are not,” his mother countered. “Now, you cannot just lie here until the princes send word. And you did not just throw in that link between the grand duchess and the King Under Stone as a point of minor interest to your story. What is happening?”

“You’re too clever,” Oliver told his mother.

“It’s why your father married me,” she said with a small smile. “Now talk, boy.”

Oliver did smile now, but it soon faded as he related the rest of the story to her. How he had told Heinrich about the shadows in the garden, and how Heinrich had taken the matter very seriously. He told her about meeting Rose and Galen, and how they, too, had seemed haunted by something.

“The King Under Stone wants them for his sons, if not for himself,” Oliver finished. “I know it. He wants Petunia.”

“I can hardly blame him,” Lady Emily said. “Beautiful girls—beautiful women, I should say—all of them.” She eyed him. “If you were a properly landed and titled earl, you would make a fine match for Petunia.”

Oliver opened his mouth and closed it again. He wasn’t thinking such things. He only wanted to help.

Didn’t he?

“Thank heavens you still have the crown prince’s invisibility cloak,” Lady Emily said with a heavy sigh. She finished darning the second stocking and put it away. Getting to her feet, she shook her head. “Just try to be careful, sneaking onto the estate. Prince Grigori, as we’ve said, is not to be trifled with.”

Oliver opened his mouth and closed it yet again, feeling like a fish gasping on the bank.

“I—I’m not—” he finally managed.

“Of course not,” his mother said drily. She bent over and kissed his forehead on her way out of the room. “I’m just glad that Simon’s injury keeps him from following you.”