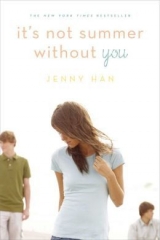

Текст книги "It's Not Summer Without You"

Автор книги: Jenny Han

Соавторы: Jenny Han

Жанр:

Подростковая литература

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

chapter twenty-one

The first time it hit me that day was when I was in the bathroom, washing the sugar off my face. There was no towel hanging up, so I opened the linen closet, and on the row below the beach towels, there was Susannah’s big floppy hat. The one she wore every time she sat on the beach. She was careful with her skin. Was.

Not thinking about Susannah, consciously not thinking about her, made it easier. Because then she wasn’t really gone . She was just off someplace else. That was what I’d been doing since she died. Not thinking about her. It was easier to do at home. But here, at the summer house, she was everywhere.

I picked her hat up, held it for a second, and then put it back on the shelf. I closed the door, and my chest hurt so bad I couldn’t breathe. It was too hard. Being there, in this house, was too hard.

I ran up the stairs as fast as I could. I took off Conrad’s necklace and I changed out of my clothes and into Taylor’s bikini. I didn’t care how stupid I looked in it. I just wanted to be in the water. I wanted to be where I didn’t have to think about anything, where nothing else existed. I would swim, and float, and breathe in and out, and just be.

My old Ralph Lauren teddy bear towel was in the linen closet just like always. I put it around my shoulders like a blanket and headed outside. Jeremiah was eating an egg sandwich and swigging from a carton of milk. “Hey,” he said.

“Hey. I’m going to swim.” I didn’t ask where Conrad was, and I didn’t invite Jeremiah to join me. I needed a moment just by myself.

I pushed the sliding door open and closed it without waiting for him to answer me. I threw my towel onto a chair and swan-dived in. I didn’t come up for air right away. I stayed down under; I held my breath until the very last second.

When I came up, I felt like I could breathe again, like my muscles were relaxing. I swam back and forth, back and forth. Here, nothing else existed. Here, I didn’t have to think. Each time I went under, I held my breath for as long as I could.

Under water, I heard Jeremiah call my name. Reluctantly I came up to the surface, and he was crouching by the side of the pool. “I’m gonna go out for a while. Maybe I’ll pick up a pizza at Nello’s,” he said, standing up.

I pushed my hair out of my eyes. “But you just ate a sandwich. And you had all those dirt bombs.”

“I’m a growing boy. And that was an hour and a half ago.”

An hour and a half ago? Had I been swimming for an hour and a half? It felt like minutes. “Oh,” I said. I examined my fingers. They were totally pruned.

“Carry on,” Jeremiah said, saluting me.

Kicking off the side of the pool, I said, “See ya.” Then I swam as quick as I could to the other side and flip-turned, just in case he was still watching. He’d always admired my flip turns.

I stayed in the pool for another hour. When I came up for air after my last lap, I saw that Conrad was sitting in the chair where I’d left my towel. He held it out to me silently.

I climbed out of the pool. Suddenly I was shivering. I took the towel from him and wrapped it around my body. He did not look at me. “Do you still pretend you’re at the Olympics?” he asked me.

I started, and then I shook my head and sat down next to him. “No,” I said, and the word hung in the air. I hugged my knees to my chest. “Not anymore.”

“When you swim,” he started to say. I thought he wasn’t going to continue, but then he said, “You wouldn’t notice if the house was on fire. You’re so into what you’re doing, it’s like you’re someplace else.”

He said it with grudging respect. Like he’d been watching me for a long time, like he’d been watching me for years. Which I guess he had.

I opened my mouth to respond, but he was already standing up, going back into the house. As he closed the sliding door, I called out, “That’s why I like it.”

chapter twenty-two

I was back in my room, about to change out of my bikini when my phone rang. It was Steven’s ringtone, a Taylor Swift song he pretended to hate but secretly loved. For a second, I thought about not answering. But if I didn’t pick up, he’d only call back until I did. He was annoying that way.

“Hello?” I said it like a question, like I didn’t already know it was Steven.

“Hey,” he said. “I don’t know where you are, but I know you’re not with Taylor.”

“How do you know that?” I whispered.

“I just ran into her at the mall. She’s worse than you at lying. Where the hell are you?”

I bit my upper lip and I said, “At the summer house. In Cousins.”

“What?” he sort of yelled. “Why?”

“It’s kind of a long story. Jeremiah needed my help with Conrad.”

“So he called you ?” My brother’s voice was incredulous and also the tiniest bit jealous.

“Yeah.” He was dying to ask me more, but I was banking on the fact that his pride wouldn’t let him. Steven hated being left out. He was silent for a moment, and in those seconds, I knew he was wondering about all the summer house stuff we were doing without him.

At last he said, “Mom’s gonna be so pissed.”

“What do you care?”

“I don’t care, but Mom will.”

“Steven, chill out. I’ll be home soon. We just have to do one last thing.”

“What last thing?” It killed him that I knew something he didn’t, that for once, he was the odd man out. I thought I’d take more pleasure in it, but I felt oddly sorry for him.

So instead of gloating the way I normally would, I said, “Conrad took off from summer school and we have to get him back in time for midterms on Monday.”

That would be the last thing I would do for him. Get him to school. And then he’d be free, and so would I.

After Steven and I got off the phone, I heard a car pull up in front of the house. I looked out the window and there was a red Honda, a car I didn’t recognize. We almost never had visitors at the summer house.

I dragged a comb through my hair and hurried down the stairs with my towel wrapped around me. I stopped when I saw Conrad open the door, and a woman walked in. She was petite, with bleached blond hair that was in a messy bun, and she wore black pants and a silk coral blouse. Her fingernails were painted to match. She had a big folder in her hand and a set of keys.

“Well, hello there,” she said. She was surprised to see him, as if she was the one who was supposed to be there and he wasn’t.

“Hello,” Conrad said. “Can I help you?”

“You must be Conrad,” she said. “We spoke on the phone. I’m Sandy Donatti, your dad’s real estate agent.”

Conrad said nothing.

She wagged her finger at him playfully. “You told me your dad changed his mind about the sale.”

When Conrad still said nothing, she looked around and saw me standing at the bottom of the stairs. She frowned and said, “I’m just here to check on the house, make sure everything’s coming along and getting packed up.”

“Yeah, I sent the movers away,” Conrad said casually.

“I really wish you hadn’t done that,” she said, her lips tight. When Conrad shrugged, she added, “I was told the house would be empty.”

“You were given erroneous information. I’ll be here for the rest of the summer.” He gestured at me. “That’s Belly.”

“Belly?” she repeated.

“Yup. She’s my girlfriend.”

I think I choked out loud.

Crossing his arms and leaning against the wall, he continued. “And you and my dad met how?”

Sandy Donatti flushed. “We met when he decided to put the house up for sale,” she snapped.

“Well, the thing is, Sandy, it’s not his house to sell. It’s my mother’s house, actually. Did my dad tell you that?”

“Yes.”

“Then I guess he also told you she’s dead.”

Sandy hesitated. Her anger seemed to evaporate at the mention of dead mothers. She was so uncomfortable, she was shifting toward the door. “Yes, he did tell me that. I’m very sorry for your loss.”

Conrad said, “Thank you, Sandy. That means a lot, coming from you.”

Her eyes darted around the room one last time. “Well, I’m going to talk things over with your dad and then I’ll be back.”

“You do that. Make sure you let him know the house is off the market.”

She pursed her lips and then opened her mouth to speak, but thought better of it. Conrad opened the door for her, and then she was gone.

I let out a big breath. A million thoughts were running through my head—I’m ashamed to say that girlfriend was pretty near the top of the list. Conrad didn’t look at me when he said, “Don’t tell Jeremiah about the house.”

“Why not?” I asked. My mind was still lingering on the word “girlfriend.”

He took so long to answer me that I was already walking back upstairs when he said, “I’ll tell him about it. I just don’t want him to know yet. About our dad.”

I stopped walking. Without thinking I said, “What do you mean?”

“You know what I mean.” Conrad looked at me, his eyes steady.

I suppose I did know. He wanted to protect Jeremiah from the fact that his dad was an asshole. But it wasn’t like Jeremiah didn’t already know who his dad was. It wasn’t like Jeremiah was some dumb kid without a clue. He had a right to know if the house was for sale.

I guessed Conrad read all of this on my face, because he said in that mocking, careless way of his, “So can you do that for me, Belly? Can you keep a secret from your BFF Jeremiah? I know you two don’t keep secrets from each other, but can you handle it just this once?”

When I glared at him, all ready to tell him what he could do with his secret, he said, “Please?” and his voice was pleading.

So I said, “All right. For now.”

“Thank you,” he said, and he brushed past me and headed upstairs. His bedroom door closed, and the air conditioning kicked on.

I stayed put.

It took a minute for everything to sink in. Conrad didn’t just run away to surf. He didn’t run away for the sake of running away. He came to save the house.

chapter twenty-three

Later that afternoon Jeremiah and Conrad went surfing again. I thought maybe Conrad wanted to tell him about the house, just the two of them. And maybe Jeremiah wanted to try and talk to Conrad about school again, just the two of them. That was fine by me. I was content just watching.

I watched them from the porch. I sat in a deck chair with my towel wrapped tight around me. There was something so comforting and right about coming out of the pool wet and your mom putting a towel around your shoulders, like a cape. Even without a mother there to do it for you, it was good, cozy. Achingly familiar in a way that made me wish I was still eight. Eight was before death or divorce or heartbreak. Eight was just eight. Hot dogs and peanut butter, mosquito bites and splinters, bikes and boogie boards. Tangled hair, sunburned shoulders, Judy Blume, in bed by nine thirty.

I sat there thinking those melancholy kinds of thoughts for a long while. Someone was barbecuing; I could smell charcoal burning. I wondered if it was the Rubensteins, or maybe it was the Tolers. I wondered if they were grilling burgers, or steak. I realized I was hungry.

I wandered into the kitchen but I couldn’t find anything to eat. Just Conrad’s beer. Taylor told me once that beer was just like bread, all carbohydrates. I figured that even though I hated the taste of it, I might as well drink it if it’d fill me up.

So I took one and walked back outside with it. I sat back down on my deck chair and popped the top off the can. It snapped very satisfyingly. It was strange to be in this house alone. Not a bad feeling, just a different one. I’d been coming to this house my whole life and I could count on one hand the number of times I’d been alone in it. I felt older now. Which I suppose I was, but I guess I didn’t remember feeling old last summer.

I took a long sip of beer and I was glad Jeremiah and Conrad weren’t there to see me, because I made a terrible face and I knew they’d give me crap for it.

I was taking another sip when I heard someone clear his throat. I looked up and I nearly choked. It was Mr. Fisher.

“Hello, Belly,” he said. He was wearing a suit, like he’d come straight from work, which he probably had, even though it was a Saturday. And somehow his suit wasn’t even rumpled, even after a long drive.

“Hi, Mr. Fisher,” I said, and my voice came out all nervous and shaky.

My first thought was, We should have just forced Conrad into the car and made him go back to school and take his stupid tests . Giving him time was a huge mistake. I could see that now. I should have pushed Jeremiah into pushing Conrad.

Mr. Fisher raised an eyebrow at my beer and I realized I was still holding it, my fingers laced around it so tight they were numb. I set the beer on the ground, and my hair fell in my face, for which I was glad. It was a moment to hide, to figure out what to say next.

I did what I always did—I deferred to the boys. “Um, so, Conrad and Jeremiah aren’t here right now.” My mind was racing. They would be back any minute.

Mr. Fisher didn’t say anything, he just nodded and rubbed the back of his neck. Then he walked up the porch steps and sat in the chair next to mine. He picked up my beer and took a long drink. “How’s Conrad?” he asked, setting the beer on his armrest.

“He’s good,” I said right away. And then I felt foolish, because he wasn’t good at all. His mother had just died. He’d run away from school. How could he be good? How could any of us? But I guess, in a sense, he was good, because he had purpose again. He had a reason. To live. He had a goal; he had an enemy. Those were good incentives. Even if the enemy was his father.

“I don’t know what that kid is thinking,” Mr. Fisher said, shaking his head.

What could I say to that? I never knew what Conrad was thinking. I was sure not many people did. Even still, I felt defensive of him. Protective.

Mr. Fisher and I sat in silence. Not companionable, easy silence, but stiff and awful. He never had anything to say to me, and I never knew what to say to him. Finally he cleared his throat and said, “How’s school?”

“It’s over,” I said, chewing on my bottom lip and feeling twelve. “Just finished. I’ll be a senior this fall.”

“Do you know where you want to go to college?”

“Not really.” The wrong answer, I knew, because college was one thing Mr. Fisher was interested in talking about. The right kind of college, I mean.

And then we were silent again.

This was also familiar. That feeling of dread, of impending doom. The feeling that I was In Trouble. That we all were.

chapter twenty-four

Milk shakes. Milk shakes were Mr. Fisher’s thing. When Mr. Fisher came to the summer house, there were milk shakes all the time. He’d buy a Neapolitan carton of ice cream. Steven and Conrad were chocolate, Jeremiah was strawberry, and I liked a vanilla-chocolate mix, like those Frosties at Wendy’s. But thick-thick. Mr. Fisher’s milk shakes were better than Wendy’s. He had a fancy blender he liked to use, that none of us kids were supposed to mess with. Not that he said so, exactly, but we knew not to. And we never did. Until Jeremiah had the idea for Kool-Aid Slurpees.

There were no 7-Elevens in Cousins, and even though we had milk shakes, we sometimes yearned for Slurpees. When it was especially hot outside, one of us would say, “Man, I want a Slurpee,” and then all of us would be thinking about it all day. So when Jeremiah had this idea for Kool-Aid Slurpees, it was, like, kismet. He was nine and I was eight, and at the time it sounded like the greatest idea in the world, ever.

We eyed the blender, way up high on the top shelf. We knew we’d have to use it—in fact we longed to use it. But there was that unspoken rule.

No one was home but the two of us. No one would have to know.

“What flavor do you want?” he asked me at last.

So it was decided. This was happening. I felt fear and also exhilaration that we were doing this forbidden thing. I rarely broke rules, but this seemed a good one to break.

“Black Cherry,” I said.

Jeremiah looked in the cabinet, but there was none. He asked, “What’s your second-best flavor?”

“Grape.”

Jeremiah said that grape Kool-Aid Slurpee sounded good to him, too. The more he said the words “Kool-Aid Slurpee,” the more I liked the sound of it.

Jeremiah got a stool and took the blender down from the top shelf. He poured the whole packet of grape into the blender and added two big plastic cups of sugar. He let me stir. Then he emptied half the ice dispenser into the blender, until it was full to the brim, and he snapped on the top the way we’d seen Mr. Fisher do it a million times.

“Pulse? Frappe?” he asked me.

I shrugged. I never paid close enough attention when Mr. Fisher used it. “Probably frappe,” I said, because I liked the sound of the word “frappe.”

So Jeremiah pushed frappe, and the blender started to chop and whir. But only the bottom part was getting mixed, so Jeremiah pushed liquefy. It kept at it for a minute, but then the blender started to smell like burning rubber, and I worried it was working too hard with all that ice.

“We’ve got to stir it up more,” I said. “Help it along.”

I got the big wooden spoon and took the top off the blender and stirred it all up. “See?” I said.

I put the top back on, but I guess I didn’t do it tight enough, because when Jeremiah pushed frappe, our grape Kool-Aid Slurpee went everywhere. All over us. All over the new white counters, all over the floor, all over Mr. Fisher’s brown leather briefcase.

We stared at each other in horror.

“Quick, get paper towels!” Jeremiah yelled, unplugging the blender. I dove for the briefcase, mopping it up with the bottom of my T-shirt. The leather was already staining, and it was sticky.

“Oh, man,” Jeremiah whispered. “He loves that briefcase.”

And he did. It had his initials engraved on the brass clasp. He truly loved it, maybe even more than his blender.

I felt terrible. Tears pricked my eyelids. It was all my fault. “I’m sorry,” I said.

Jeremiah was on the floor, on his hands and knees wiping. He looked up at me, grape Kool-Aid dripping down his forehead. “It’s not your fault.”

“Yeah, it is,” I said, rubbing at the leather. My T-shirt was starting to turn brown from rubbing at the briefcase so hard.

“Well, yeah, it kinda is,” Jeremiah agreed. Then he reached out and touched his finger to my cheek and licked off some of the sugar. “Tastes good, though.”

We were giggling and sliding our feet along the floor with paper towels when everyone came back home. They walked in with long paper bags, the kind the lobsters come in, and Steven and Conrad had ice-cream cones.

Mr. Fisher said, “What the hell?”

Jeremiah scrambled up. “We were just—”

I handed the briefcase over to Mr. Fisher, my hand shaking. “I’m sorry,” I whispered. “It was an accident.”

He took it from me and looked at it, at the smeared leather. “Why were you using my blender?” Mr. Fisher demanded, but he was asking Jeremiah. His neck was bright red. “You know you’re not to use my blender.”

Jeremiah nodded. “I’m sorry,” he said.

“It was my fault,” I said in a small voice.

“Oh, Belly,” my mother said, shaking her head at me. She knelt on the ground and picked up the soaked paper towels. Susannah had gone to get the mop.

Mr. Fisher exhaled loudly. “Why don’t you ever listen when I tell you something? For God’s sake. Did I or did I not tell you to never use this blender?”

Jeremiah bit his lip, and from the way his chin was quivering, I could tell he was really close to crying.

“Answer me when I’m talking to you.”

Susannah came back in then with her mop and bucket. “Adam, it was an accident. Let it go.” She put her arms around Jeremiah.

“Suze, if you baby him, he’ll never learn. He’ll just stay a little baby,” Mr. Fisher said. “Jere, did I or did I not tell you kids never to use the blender?”

Jeremiah’s eyes filled up and he blinked quickly, but a few tears escaped. And then a few more. It was awful. I felt so embarrassed for Jeremiah and also I felt guilty that it was me who had brought all this upon him. But I also felt relieved that it wasn’t me who was the one getting in trouble, crying in front of everyone.

And then Conrad said, “But Dad, you never did.” He had chocolate ice cream on his cheek.

Mr. Fisher turned and looked at him. “What?”

“You never said it. We knew we weren’t supposed to, but you never technically said it.” Conrad looked scared, but his voice was matter-of-fact.

Mr. Fisher shook his head and looked back at Jeremiah. “Go get cleaned up,” he said roughly. He was embarrassed, I could tell.

Susannah glared at him and swept Jeremiah into the bathroom. My mother was wiping down the counters, her shoulders straight and stiff. “Steven, take your sister to the bathroom,” she said. Her voice left no room for argument, and Steven grabbed my arm and took me upstairs.

“Do you think I’m in trouble?” I asked Steven.

He wiped my cheeks roughly with a wet piece of toilet paper. “Yes. But not as much trouble as Mr. Fisher. Mom’s gonna rip him a new one.”

“What does that mean?”

Steven shrugged. “Just something I heard. It means he’s the one in trouble.”

After my face was clean, Steven and I crept back into the hallway. My mother and Mr. Fisher were arguing. We looked at each other, our eyes huge when we heard our mother snap, “You can be such an ass-hat, Adam.”

I opened my mouth, about to exclaim, when Steven clapped his hand over my mouth and dragged me to the boys’ room. He shut the door behind us. His eyes were glittery from all the excitement. Our mother had cussed at Mr. Fisher.

I said, “Mom called Mr. Fisher an ass-hat.” I didn’t even know what an ass-hat was, but it sure sounded funny. I pictured a hat that looked like a butt sitting on top of Mr. Fisher’s big head. And then I giggled.

It was all very exciting and terrible. None of us had ever really gotten in trouble at the summer house. Not big trouble anyway. It was pretty much a big trouble-free zone.

The mothers were relaxed at the summer house. Where at home, Steven would Get It if he talked back, here, my mother didn’t seem to mind as much. Probably because at the Cousins house, us kids weren’t the center of the world. My mother was busy doing other things, like potting plants and going to art galleries with Susannah and sketching and reading books. She was too busy to get angry or bothered. We did not have her full attention.

This was both a good and bad thing. Good, because we got away with stuff. If we played out on the beach past bedtime, if we had double dessert, no one really cared. Bad, because I had the vague sense that Steven and I weren’t as important here, that there were other things that occupied my mother’s mind—memories we had no part of, a life before we existed. And also, the secret life inside herself, where Steven and I didn’t exist. It was like when she went on her trips without us—I knew that she did not miss us or think about us very much.

I hated that thought, but it was the truth. The mothers had a whole life separate from us. I guess us kids did too.