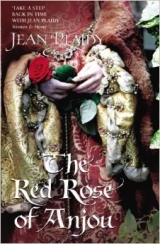

Текст книги "The Red Rose of Anjou"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

This was, as René had known it would be, construed as an insult by the Vaudémonts and they protested. They were going to take the matter to parliament, they declared. They were going to set it before the King and see what he thought about such injustice.

All well and good, thought René. Delay...delay...that is always a good policy.

‘Why have you done this?’ Margaret asked him. ‘You must have known what the result would be.’

‘I did it for that reason.’

‘But why. Father?’

‘May I ask you a question. Do you want to marry the Count of Nevers?’

Margaret considered calmly. ‘I have to marry someone,’ she said.

‘But you can imagine someone younger...someone more romantic...than a middle-aged Count, perhaps?’

‘Why, yes, of course.’

‘Then you don’t want to marry him? You would rather wait awhile. Who knows what gallant suitor might come forth? Is that so, dear child?’

‘Yes, Father. I do not want to marry the Count of Nevers.’

‘So I thought,’ said René. ‘Now we will settle down to wait.’

MARGARET AND HENRY

The King was riding from St. Albans to Westminster. He was waiting impatiently for the return of Champchevrier. The thought of this young girl whose father had become impoverished through a series of misadventures appealed to him. Henry was always sorry for the failures. Perhaps it was because he sometimes felt he was a failure himself. He often wished that fate had not made him a King. Sometimes he imagined what he would have been if he had not been born royal. He might have gone into a monastery where he could have spent his days illuminating manuscripts, praying, working for the poor. He would have been content doing that and he would have done it well.

But he was the son of a King, a King in his own right, and as such was burdened by responsibilities which he could not endure.

He had not been formed to be a King – and a Plantagenet King at that. He did not belong with those blond long-legged giants who only had to wave a banner to have men flock to them. They had imposed their iron rule on the people – or most of them had – and the people had accepted it, almost always. Edward Longshanks; Edward the Third; his own father, Great Henry the Fifth. They were all kings of whom England could be proud.

And then had come Henry, a King at nine months old, surrounded by ambitious men all jostling for power. No, he was apart. His ancestors in the main had been lusty men. They had scattered their bastards all over the country. But he was different. He believed in chastity and the sanctity of the marriage vows. He was acutely embarrassed when women approached him seeking to tempt him, as they used to. They did not do it so much now because they knew it was useless; but there would always be women who would be delighted to become the King’s mistress. Never, he had said, and turned disgustedly away.

He remembered one occasion when some of his courtiers had arranged for dancers to perform for him and they came before him, their bosoms bare. So horrified had he been that he had quickly quitted the chamber muttering the nearest expletive to an oath of which he was capable, ‘Forsooth and forsooth.’ And then ‘Fie, for shame! You are to blame for bringing such women before me.’ And he had refused to look at them.

It needed incidents like that to assure those about him that he really was a deeply religious man of genuine purity.

Very laudable in a priest. But a King!

All he wanted was to live quietly, in a peaceful household; he wanted no more of the conflict in France. Did he want to be King of France? He did not want to be King of England even! His great uncle Cardinal Beaufort had assured him that with the death of his uncle Bedford the hopes of retaining a hold on France had ended. Everything had changed since the glorious days of Barfleur and Agincourt. Then England had had a great warrior King and had he lived doubtless France and England would be one by now. But he had died and Joan of Arc had come forward and changed the war. She was dead now...burned as a witch and he was still horrified by the memory of that deed. He had seen her once when he was a boy and had peeped at her through an aperture in the wall and looked into her cell; he had never forgotten her. He was certain now that she had been sent from Heaven. It was a sign that God wanted France to remain in the hands of the French. Henry wanted it too.

The great Cardinal on whom he relied had said that the time had come to make peace with the French—an honourable peace before they had lost too much.

Heartily Henry agreed with that. Others did too. There was one notable exception: Henry’s uncle Gloucester. Henry disliked and feared his uncle Gloucester. He was nothing but a troublemaker and his wife was now a captive in one of the country’s castles because she had indulged in witchcraft in an attempt to destroy Henry’s life.

For what reason? So that Gloucester could be King as he was the next in line.

No, Henry would never trust Gloucester. He did not want him near him. He had given orders that he must have extra guards and if ever his uncle Gloucester attempted to approach him they must watch most carefully.

It was the Cardinal who had suggested that a marriage with Margaret of Anjou might be a good thing. A French marriage was necessary. The King of France was disinclined to offer one of his daughters. ‘At one time we could have insisted,’ said the Cardinal, ‘but times have changed and the sooner we take account of this the better. Margaret is the niece of the Queen of France; she is a Princess even if René is only titular King of Naples. She is young and could be taught. It seems to me, my lord, that Margaret would be a very good proposition.’

He had agreed as he invariably did with the Cardinal and the fact that he knew his uncle Gloucester would be against the match made it seem doubly attractive.

And because of that he had sent Champchevrier to France to bring to him, secretly, a picture of Margaret, for it must not yet be known that a match was being thought of. He wanted to make sure that his prospective bride was indeed a young pure girl. He wanted no brazenly voluptuous woman, but he would like one who was beautiful; he had a great love for beauty, usually in painting, poetry and music, so his wife must appeal to his aesthetic tastes. He planned to live with her as a good husband and if she would be a good wife to him they would remain faithful until death parted them and in the meantime give the country the necessary heir.

The Duke of Gloucester was in favour of a match with one of the daughters of the Count of Armagnac. Armagnac was not at this time friendly with the King of France and the last thing Gloucester wanted was peace with France. Henry was not sure whether Gloucester wanted the conflict to persist because he saw himself as a great warrior like his brother Henry the Fifth and had dreams of bringing the French crown to England or whether he wanted the match because the Cardinal was against it. But any match that Gloucester would arrange for him could never please Henry. He had, however, diplomatically dispatched Hans to the Court of Armagnac, telling him there was no need for haste, and at the same time had sent Champchevrier out in secret and in all speed.

The Cardinal had seen and conversed with Margaret and had reported that not only was she a beautiful girl but she was an intelligent one.

When Champchevrier returned he would first make his way to Westminster and Henry wished to be there when he came, to save delay. It was for this reason that he was now on his way.

As he approached the capital he was recognized and cheered by a few people. They were not wildly enthusiastic for he was not a man who could inspire that frenzied admiration in them which they had accorded to some of his ancestors and it was always difficult in any case for the living to compare favourably with the dead.

Coming into Cripplegate something stuck on a stake caught his eye. He looked at it in puzzlement not recognizing it for what it was. Then he turned to one of his attendants and said: ‘What is that revolting object?’

‘My lord,’ was the answer, ‘it is the quarters of some wretch who has been punished for treason to yourself.’

Henry covered his eyes with his hands. ‘It disgusts me,’ he said. ‘Have it taken away. It does not please me that my subjects should be so treated for my sake.’

‘This man was a traitor, my lord. Proved to be so.’

‘Traitors should die mayhap, but not in such a way. Have that rotting flesh taken down at once. I never want to see the like again.’

His orders were obeyed but he knew they were asking themselves, What manner of King is this?

On to Westminster. Champchevrier had not yet arrived. Henry settled down to wait with patience.

He had so much to absorb his interest at this time. He was deeply involved in plans for founding colleges at Eton and Cambridge. One of the greatest joys in life was learning and he wanted to do all he could to promote it. The planning of these colleges pleased him more than anything at this time and he dearly wished that he could give more time to such projects instead of the continual preoccupation with continuing the war in France. He saw quite clearly that no good could come of this war. It had been going on for a hundred years and still nothing was resolved. It was like a seesaw, first England was in the ascendant and then dashed down to the ground; up went France and then down...It would go on like that and it meant nothing but bloodshed for the men who went to France and excessive taxation for those who remained behind.

There was no joy in war. He would like to end it as soon as possible and this French marriage would be a step towards it.

He was delighted when Champchevrier finally arrived in Westminster with the picture. He had pilfered it from the castle of Tarascon, he explained, where by strategy, posing as a traveller, he had spent a night.

Henry seized the picture eagerly. A pair of gentle blue eyes looked at him out of a heart-shaped face; the brow was high, indicating intelligence, the expression serene and her hair hung about her shoulders—fair with tints of red in it.

‘My lord, you like the picture?’ asked Champchevrier.

‘By St. John, yes I do.’

It was the nearest Henry could come to an oath but it meant that he liked what he saw—he liked it very much.

###

The Cardinal Beaufort was riding to Westminster. He had urgent business with the King but before he went to Henry he wished to sound the Earl of Suffolk, for the Cardinal had selected the Earl as the most suitable of all the English nobles to conduct the business ahead of them.

The Cardinal was thoughtful. He was getting near to the end of a full and very satisfying life. Born bastard son of John of Gaunt and Catherine Swynford he had been legitimized by his father and had enjoyed many honours. He had played a large part in the government of the country since his half-brother Henry IV had taken the crown from poor ineffectual Richard and so set up the House of Lancaster as the ruling one.

At one time it had seemed that the dream of capturing the crown of France would be realized. And so it would have been if Henry the Fifth had lived. Henry had a genius for war and when he married the French Princess and it was agreed that he should have the throne on the death of mad Charles it seemed that the war was virtually over. But change comes quickly and unexpectedly especially in the history of countries at war. Who would have believed twenty years before that the crown of France should have been saved for the French by a peasant girl and that Charles the Dauphin, indolent, careless of anything but his own pleasure, listless, indifferent to the fate of his country, should become one of the most astute Kings that France had ever known?

There was one truth which had been apparent to the Cardinal for a very long time and that was that England had lost the war for France and that the sooner this was realized and the best terms made, the better.

But there was certain to be differing points of view and the Duke of Gloucester, in spite of everything that had happened, was still a force to be reckoned with.

Gloucester did not want peace with France. He still dreamed that he was going to win spectacular battles like Agincourt. He really believed he was a military genius like his brother. Even Bedford had not been that, great soldier though he had been and wise administrator too. There was none to compare with Henry the Fifth. His kind appeared only once in a century. And Gloucester thought he could achieve what his brother had! It was contemptible.

It was a pity Gloucester had not been found guilty of practising witchcraft when his wife had.

But for some reason Gloucester was popular with the people. It was some strange charismatic quality he had. Many of the Plantagenets had it—it was a family gift, though it missed some. For all his excellence Bedford never had it. Henry the Fifth had had a double dose of it. And oddly enough, Gloucester, who had a genius for backing the wrong causes and made a failure of everything he tackled, who had married a woman far beneath him socially who was now charged with sorcery...all this and the people still retained a certain tenderness for him. So in spite of everything Gloucester still had to be reckoned with.

And Gloucester wanted to continue this disastrous war.

Therefore there must be a certain secrecy about these arrangements for Henry’s marriage. A Princess of Anjou was the best they could hope for. It was no use trying to badger Charles for one of his own daughters. England alas was not in a position to make demands any more. A marriage with Armagnac would be tantamount to a pledge to continue the war, so that was the last thing they needed. Charles might be pleased to permit the marriage of his niece—she was in fact his wife’s niece—and he might consider that it was a very good match for Margaret of Anjou, which it was. She would be Queen of England and if that was not a dazzling prospect for the younger daughter of an impoverished man who was only titular King of Naples, Beaufort did not know what was.

He had selected the man who should be the chief ambassador to the Court of Anjou and he was going to see him before he went to the King. Indeed, he thought they should go together without

delay to the King so that the negotiations could be put into practice immediately.

When the Cardinal arrived at Westminster he went at once to the Earl of Suffolk’s apartments before seeking an audience with the King.

Suffolk was delighted to see him while at the same time he wondered if this might mean trouble or some unpleasant task for him. He and the Cardinal worked closely together; and they were both sworn enemies of Gloucester.

William de la Pole had become the Earl of Suffolk when his elder brother was killed at Agincourt. He had had a distinguished military career and after the death of Henry the Fifth had served under the Duke of Bedford. He had been with Salisbury at the siege of Orléans. He had seen the mysterious death of Salisbury and the coming of the Maid.

He knew, as the Cardinal did, that those English hopes which had seemed so bright before the siege of Orléans, had become depressingly dim. England should slip out of France and try to keep as many of her old possessions as possible. Only hotheads like Gloucester would disagree with this.

Since his marriage he had formed a connection with the Beaufort family for his wife was the widow of the Earl of Salisbury and she had been Alice Chaucer before her marriage. Catherine Swynford—the mother of the Beauforts—had had a sister Philippa who had married the poet Geoffrey Chaucer and so there was a family connection.

His long military career made him feel very strongly that peace was necessary and he and the Cardinal had often discussed the best way of achieving this.

Now the Cardinal thought he had found a way.

‘A marriage with Margaret of Anjou could be a stepping stone to peace,’ he told Suffolk when they had exchanged the customary pleasantries.

‘And the King, will he agree to marriage?’

‘He wants it. He knows he has to marry sooner or later. It is his duty to provide an heir and though he has little interest in women he will do his duty. We can count on him for that. In fact he has sent a secret messenger to France to find a picture of her and he is delighted with what he sees.’

‘The pictures of Princesses have been known to flatter.’

‘Well, what would that matter? He would be half way in love with her before she arrived and that can do no harm. Moreover, I have seen her. I found her good-looking, intelligent and vivacious. In fact, everything that Henry needs in a wife.’

‘And of course there are the marriage terms to be arranged.’

‘What we need is a peace treaty. I want this marriage to mean that we abandon our claim to the crown of France.’

‘And do you think the people will accept that?’

‘They have to be convinced it is best.’

‘They are intoxicated by victories like Agincourt and Verneuil. They do not understand why we don’t go on providing them with glorious occasions like those.’

‘The people will accept what has to be done. Give them a royal wedding and they will be happy.’

‘They do not like the French.’

‘They loved Katherine of Valois.’

‘She came in rather different circumstances. When she married Henry it was in victory. He had won France they thought, and was taking the French Princess to make a happy solution for both countries.’

‘What is wrong with you, William? It almost seems that you would put obstacles in the way of this match.’

Suffolk was silent. Then he said: ‘I have a notion that you have decided that I shall go as the King’s proxy to Margaret of Anjou.’

‘Who would be better?’

‘I knew it. It is why you wished to speak to me.’

‘You are a man of maturity and wisdom, William. It is clear to me that you are the one to go to Anjou to treat with the King of France, for that is what it will mean.’

‘You know. Cardinal, that the King of France is a shrewd man. It is not the old Dauphin we have to deal with. Whenever I think of Charles of France I say to myself "There is Joan of Arc’s miracle."‘

‘Yes, Charles has changed. There are such changes. I remember my own nephew, Henry the Fifth—a profligate youth who filled us all with misgivings and then once the crown was on his head he became the hero of Agincourt.’

‘I shall have to barter with the King of France.’

‘It will certainly come to that.’

‘And we shall have to sacrifice something for Margaret. And it will be land, castles...you can be sure of that.’

‘But of course.’

‘And the people are not going to like the sort of sacrifice for which Charles will ask.’

‘Nevertheless the sacrifice will have to be made.’

‘And they will blame the one who made it. Not the King, not the Cardinal, but their ambassador Suffolk. I can imagine what Gloucester will make of that.’

‘So that is what holds you back.’

Suffolk was silent for a few moments.

‘I feel that the people will not like a French marriage and when they hear we have had to sacrifice territory won in battle they will blame the one who made those concessions, that is the King’s ambassador, otherwise Suffolk...if he goes.’

The Cardinal moved closer to Suffolk.

‘But have you thought how grateful the new Queen will be to the man who brought her to England and so skilfully arranged the necessary details for her marriage? The man who has the Queen’s favour will be fortunate indeed. The King is not a very forceful character, is he? I can see him relying on his Queen and then the one she favours will be in a very happy position indeed.’

Suffolk was thoughtful. There might be something in that but there were too many conditions attached. No, he would prefer not to be involved in anything like this. He was getting too old. He would be forty-eight in October. Not that he wanted to disengage himself from politics, but at least he did not want to run into anything that might be uncomfortable or even dangerous.

‘I would rather not be the King’s ambassador on this occasion,’ he said.

The Cardinal shrugged his shoulders.

A few days later the King sent for Suffolk. He wanted him to undertake a delicate mission and Henry was sure he was the best man for the task.

He did not have to ask. He knew the nature of the order. He was to go to France, leading an embassy to arrange terms for the King’s marriage to Margaret of Anjou.

###

It was on a windy March day when the embassy landed at Barfleur. Still uneasy, Suffolk congratulated himself that at least he had the King’s assurance that no charge should be brought against him if he ran into danger, which meant that he should not be blamed if this proved to be an unpopular move.

They joined the Due d’Orléans at Blois and from there sailed down the Loire to Tours where the Court was and in due course Suffolk was presented to Charles at his Château of Montils-lès-Tours.

Suffolk was amazed by the change in the King of France. Here was a shrewd and resolute monarch, and it was an astonishing fact that the change had been brought about by women. First the Maid and then his wife and his mother-in-law Yolande of Aragon; and now, it was said, Agnès Sorel.

That the new Charles was going to drive a hard bargain was apparent. He would not give Henry one of his own daughters which he could easily have done; but Margaret, he implied, was good enough for Henry. She was a French Princess and the French were no longer in the position they had been in when Katherine the present King’s sister was given to Henry the Fifth.

Charles was not inclined to agree to a peace treaty. Why should he, with everything going in his favour? He would agree to a truce, of course; but he implied that the only thing which could bring about peace was for England to give up all claim to the French crown.

René of Anjou expressed himself dubious. Could he give his daughter to one who had usurped his hereditary dominions of Anjou and Maine?

This was an indication of what terms would be demanded.

Suffolk was relieved to escape from the conference and return to his wife. He was glad he had brought Alice with him for he could talk to her as he could to no one else.

‘I like not this matter,’ he said. I can see what will happen. The French will make great demands and the King will accept them because he wants peace and Margaret. And later when it is realized what we have had to pay for her, the people will blame me.’

‘You have the King’s assurance that no blame shall be attached to you.’

‘The assurances of Kings don’t account for much in matters like this.’

‘What can you do?’

‘I cannot agree to give up Anjou and Maine, of course. I don’t know whether a truce will be acceptable when peace terms were required. I have achieved very little advantage for ourselves.’

‘And what is Margaret’s dowry to be?’

‘There again, they seem to set a high store on this young girl who has only recently acquired the status of Princess and even then her father has nothing more than a hollow title.’

‘Alas,’ said Alice, ‘it shows how low England has fallen when you remember it is only a little more than two years ago when it was England who was calling the tune.’

‘Which brings us back to the Maid of Orléans who brought about the change. Charles is a different man from the Dauphin.’

‘They say it is Agnès Sorel who has changed him.’

‘It is amazing that women should have had such an effect on men.’

‘It often happens,’ retorted Alice, ‘although less rarely so spectacularly. Perhaps it is because Charles is a king that it is so noticeable. But what will you do, William?’

‘I can see only one course of action. I shall return home and put the proposals before the council.’

‘Very wise,’ she commented. ‘Let it be their decision not yours. It is well in such matters to be only the ambassador.’

So they travelled down to the coast and set sail for England.

###

Suffolk faced the Parliament. He had already laid the proposition before the King and the Cardinal. The French were asking a great deal but the King was becoming more and more enamoured of the idea of marriage with Margaret of Anjou and the Cardinal saw it as important to peace and although the demands for Maine and Anjou had startled them at first, they were wavering and were coming to the decision that anything was acceptable which would bring about the marriage.

To make matters worse, Margaret’s dowry was to be the islands of Majorca and Minorca which were of no value at all, for although René claimed to have inherited them from his mother, Yolande had had no jurisdiction over them. In fact all René had to offer was titles. There could rarely have been a man who had so many titles and so few possessions.

The Duke of Gloucester stood up and loudly opposed the marriage.

It was humiliating, he said, for the King of England to contemplate marrying a lady without possessions whose title to Princess was suspect, who demanded everything and gave nothing. He and his party—which was quite significant– opposed the match. He would do everything in his power to prevent it. It was giving way to the French; it was playing into Charles’s hands. They could be sure their enemies were laughing at them. Forget this marriage with Anjou. Let the King take one of the daughters of the Count of Armagnac and then let them prosecute the war and win back all they had lost because of the weak policy they had followed since the death of his brother the Duke of Bedford.

The Cardinal rose to oppose Gloucester. The enmity between them which had lasted for years was as strong as ever.

The Cardinal pleaded for peace. The country needed peace. Those who thought otherwise had no knowledge of what was happening in France.

Gloucester was on his feet. He was a soldier, he reminded them, a man who had conducted campaign after campaign.

‘With considerable failure,’ commented the Cardinal.

Gloucester, red in the face, almost foaming at the mouth, spat out at his uncle, ‘And you, my lord, you man of the Church, what do you know of military campaigns?’

I know, my lord, whether they succeed or not and we cannot afford more failures. The people will not agree to go on being taxed for a war that brings us no gain.’

‘My brother the King...’

‘Your brother the King was one of the most successful generals the world has known. Alas, he is dead, and his victories have gone with him. Times have changed. The French are in the ascendant. To carry on a war in France with all the attendant difficulties of transport and supplies is impossible. We need peace. And if the French will only give us a truce let us take it.’

The Parliament had grown accustomed to listening to the Cardinal. The late King and Bedford had relied on his judgment. He was known to be a man who served the Crown well, whereas Gloucester, popular as he might be in some quarters, was renowned for his rashness.

And the King clearly wanted the marriage.

The Parliament was therefore persuaded that the marriage with Anjou would be good for the country and it was agreed that the terms for a truce would be accepted and the question of Maine and Anjou should be left open to be discussed at some later date. So Suffolk was sent back to France to arrange the marriage by proxy.

For his services in this matter he was awarded the title of Marquess.

###

Theophanie was in a state bordering between bliss and sorrow. She was going to lose her charge and yet the young girl, who had so little in possessions to offer a bridegroom, was going to make a brilliant marriage, for although she was going to marry the enemy she would be a Queen and a real Queen at that. Not like her father and mother who called themselves King and Queen and had no country to rule.

Oh, she was proud of her Margaret. So would her grandmother the lady Yolande have been if she could see her today.

Margaret herself did not seem greatly impressed.

‘You don’t seem to want to be Queen of England,’ Theophanie complained.

‘England has been our enemy, Theophanie. Have you forgotten how we used to watch out for the soldiers and how alarmed everyone was when they were near?’

‘Young ladies like you were born to end these wars. I always reckoned you did more with your pretty looks than the men did with their cannons and cross bows.’

‘You mean alliances. I am just a counter in the game, Theophanie.’

‘Oh, you’re more than that. You’re like your mother and your grandmother. You’re going to be one of those women who do the ruling. I’ve always seen that in you.’

‘It will be strange to be in a foreign country away from you all.’

Theophanie was saddened and put up her hand to knock away a tear with a degree of impatience. ‘It’s always the same with us nurses,’ she said. ‘We have our babies and then they are snatched away from us. Kings and Queens and noblemen lose their daughters when they become ready for marriage. It’s only the poor who can keep their children with them. You’ll have to promise me never to forget old Theophanie and what she taught you when you are Queen of England.’

Poor Theophanie, she felt the parting deeply. Margaret did too. It was the end of her girlhood. She was going to a new country and a husband. She wondered a great deal about Henry.

Her parents were to escort her to Nancy where the proxy ceremony would take place. The King of France would attend, for her marriage was of importance to France. She knew that. She would see her aunt Marie and Agnès again.

Her father talked to her about the marriage as he painted, for he was loth to leave the picture he was working on.

‘It never seems the same when one comes back to it,’ he said. ‘When people produce works of art they should live with them, stay with them night and day until they are completed.’

‘Dear Father,’ she replied, ‘I am sorry my marriage is taking you away from the work you love.’

‘I was joking,’ he said. ‘Of course I want to be at my daughter’s wedding. Do you realize what you are doing for France...for us all by this marriage?’

‘Yes,’ she answered.

‘You will be in a place of authority. You will be able to guide the King to act in favour of your country.’