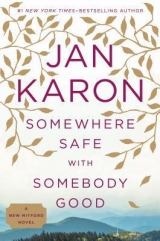

Текст книги "Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good"

Автор книги: Jan Karon

Жанры:

Современные любовные романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

‘Thank you for coming to see me, Henry. It means a great deal.’

‘I came to thank you. But for you and your son, I was gone from this world. You were part of what forced me to this.’ He touched his bald pate. ‘Some actually call it fashion, I call it penance . . . though in the end, maybe that’s just more bull. Who knows?’

‘Mary?’

‘Gone from me completely. The wonder is that she stuck it out so long. I feel utterly naked, she was my shield and defender. If I’m to have any shield now, it must be God himself. There’s no one for me and everyone against me.’

‘I’m for you.’

‘I guess I believe it or I couldn’t be here. I’ve been sick, and I’m not well yet. I don’t know if I was ever quite well or ever can be.’

‘I remember,’ he said, ‘not knowing if I was ever well or ever could be. I was ordained, and yet all the seasons were Lenten; there was no relationship with him. I was a soul in prison, bound to stick it out and go on with the show of being his man.’

‘What changed?’

‘I think you could say I came to the end of myself. I really did want a show all my own, and he had to hammer me pretty hard to make me see that it was all his. We don’t like relinquishing the power we never had anyway, even though running the show ourselves never works.

‘I surrendered everything to him. What did I have to lose? What I had to gain was—believe it, Henry—everything. It’s so simple that it baffles us; we’re more enamored of what’s grinding and hard.’

‘Grinding and hard. Yes. Pray for me.’

‘I do pray for you. I believe quite a few in this town pray for you.’

‘I could never have said this a few weeks ago. But I want what you have.’

‘What I’ve come to have—out of all that was grinding and hard—is a relationship. Bonhoeffer said it’s not about hero worship, but intimacy with God.’

‘No. I can’t do the relationship business.’

‘From the Miserere Mei, Deus. “Make me hear of joy and gladness, that the body you have broken may rejoice.” You can have joy and gladness just as I got it, by petitioning God in a simple prayer delivered with a full heart.’

‘I’m not ready for . . . intimacy. I want it, but it terrifies me. What is close and visceral has always terrified me.’

‘It terrified me,’ he said. ‘Stood my hair on end—back when I had any to stand.’

It was mighty good to laugh.

Chapter Twenty-six

Their turkey order was in at the Local, the side dishes planned, the invitations out. All but Louella’s.

CNN was busy covering the world on Louella’s big-screen TV. He sat on the stool and took her hand.

‘You’re the gravy on our biscuit, Cynthia says. And we don’t see you half enough. Dooley will be home at Thanksgiving—could you come for dinner at our house? I’ll pick you up and deliver you back no worse for wear.’

‘Only place I go to supper these times is down th’ hall or Room Number One. I would sho’ like to do it, honey, but I’m past all that.’

He rattled off the menu. ‘I could bring you a plate.’

‘No, no, y’all go on an’ have a happy time an’ bring Dooley up to visit when you can. He’ll be good medicine for me an’ everybody else.’

‘I’ll see what I can do.’

She glanced at CNN, writ large on her wall.

‘What you think about these politics goin’ on?’

‘We must pray for wisdom,’ he said.

She leaned forward, cupped her ear. ‘Who’s William?’

• • •

THEY WOULDN’T ATTEND the All-Church Feast this year, they would have their feast at home. Dooley, Lace, Sammy, Kenny, Olivia, Hélène, Harley, Coot—the democratic system at work. Ten of them around the table set up in the study, with take-outs for the Murphys and Coot.

Dooley would actually have three Thanksgiving dinners. One at the yellow house; one with his mother and Buck, Jessie and Pooh; and a third with Marge, Hal, and Rebecca on the following day at Meadowgate, a feast to which he and Cynthia and Lace and Sammy and Kenny and Pooh and Jessie were also invited, along with his proffered ham.

So, okay. For the dinner on Wisteria Lane, he would pick up the turkey from Avis and the yeast rolls from Winnie; Puny would make a sweet potato soufflé; and Cynthia would do a classic green bean casserole and two pumpkin pies, sweetened with something parading as sugar.

Oh, and the cranberry relish, which he would concoct, and so forth and so on.

His head was spinning.

• • •

‘DARLING, please deliver yourself to the Collar Button man at three o’clock on Tuesday.’

‘Whatever for?’

‘He’s going to measure you.’

A startling thing to be told. ‘I don’t want to be measured.’

‘And wear your leading citizen ribbon.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it sets an example for your successor next year. It’s a lovely thing to be seen wearing. It gives people an uplift, I should think, knowing that we even have a leading citizen.’

‘What am I being measured for? A clown suit?’

‘That’s close,’ she said.

• • •

THE COLLAR BUTTON MAN lit a match, applied the flame to the bowl of his pipe, and there went the fond habit of puffing away to get the thing going.

‘Mrs. Kavanagh wants you to have an especially nice suit, Father.’

‘I have a nice suit.’

‘Where did you get it, may I ask?’

‘At the Suit Barn.’

‘That is not a nice suit. Trust me.’ The tobacco kindled, glowed. The Collar Button man smiled as if transported.

He had never taken a vow of poverty, but a bespoke suit? Throwing dollars down the drain. And what if he gained an ounce or two? Or more to the point, lost five pounds as he was hoping to do before Christmas?

There was no wiggle room in any article of bespoke clothing. It was made to fit the person one is right now, at the very moment of measurement, when only moments later, one would no longer be that same person.

‘Surely you won’t be tailoring it?’

‘Surely not! It will be done by a distinguished tailor in New York City, which will take rather a long while and be completely worth the wait.’

The Collar Button man drew on his pipe, exhaled. The cherry-scented smoke formed a minor halo above the proprietor’s head. ‘It will last a lifetime, and make your wife very happy into the bargain.’

‘Well, there you go,’ he said. ‘Measure away.’

• • •

THE CORKBOARD WAS EXPANDING its subject range.

‘The happiness of life is made up of minute fractions—the little soon forgotten charities of a kiss or smile, a kind look, a heartfelt compliment, and the countless infinitesimals of pleasurable and genial feelings.’ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The countless infinitesimals. He had enjoyed these with great thanksgiving, and if preference could be had in this life, he would take infinitesimals any day.

Coot was dusting the rubber plant—a bloody nuisance which he would like to toss out the door. The garbage guys would be amazed to see the monstrous thing sitting on the sidewalk.

He called Hope. ‘I was wondering . . . what do you think . . . could we get rid of the rubber plant?’

‘The customer who gave it to me is still living,’ she said. That was a no.

‘So she visits the bookstore regularly?’

‘Only on occasion. She calls in her order and Scott delivers it to her door when he goes down the mountain.’

‘So . . . ?’

‘I think it’s not yet safe to give it away.’

‘Actually, we couldn’t give it away. Trust me.’

She laughed. ‘Whatever you decide, Father. I’ll leave the dirty work to you.’

While popping a few raisins, he had an idea. The red paint left from doing his basement door would give the faded pot new life.

‘If you could put a little polish on the leaves,’ he said to Coot.

He queried Marcie when she came in to place an order with their distributor.

‘I don’t know, Father. It’s not that bad now that Coot shined it up. It looks almost real.’

‘You think someone would give money for it?’

‘I wouldn’t go that far, but you never know.’

‘One man’s trash,’ he said, quoting a sign on a Wesley junk shop, ‘is another man’s bling.’

• • •

BRAHMS WAS THE COMPOSER of the day. Not the best pairing for Quo Vadis, but such was life. He dug the book out of his backpack and put it on the counter. Winnie had just arrived with a sugar-free cookie for the bookseller, ready to spend her fifteen-minute break with the poets.

‘Lord help,’ she said, ‘here comes Shirlene. It’s forty-eight degrees out there, she’ll be a popsicle.’

The caftan of the day was azure, as he believed his wife might call it. Printed with foaming waves washing onto a sandy shore and a random display of seashells. Somewhere around Shirlene’s equator were distant islands with palm trees.

‘I don’t know, I just don’t know,’ Winnie said to him, sotto voce. ‘Aren’t you freezin’, Shirlene?’

‘No, I’m burnin’ up. Flashin’ all over the place. But you know what I want, more than anything? For people when they see me to be reminded in their hearts . . .’ She lifted her arms; mountains rose from a tropical sea. ‘. . . that somewhere on the planet the sun is shinin’, the waves are breakin’ on the beach, and all is well with this troubled world. That is so important.’

‘Well, there you go,’ said Winnie. ‘You’re doin’ a service. Which I myself will be doin’ shortly by goin’ back to work.’

‘What’s up?’ he asked Shirlene.

‘Look at this, Father, an’ see what you think.’

She opened her book on dog breeds and laid it on the counter. ‘I can’t really find a picture of th’ dog I have in mind, I don’t know what breed it is. But here’s one I guess would be okay. I might go look for one like this at th’ shelter. What do you think?’

‘You will never find this breed at the shelter. Not the Wesley shelter, anyway.’

‘Why not?’

‘This is an expensive dog, not the sort you’d find in these hills.’

‘Expensive dogs get lost and run away, too.’

Winnie peered at the photograph. ‘You would have to go to Los Angelees, California, to find that poor thing wanderin’ th’ street. Maybe you should just go to the shelter and see what they have.’

And in swung Omer Cunningham in his aviator cap with earflaps, and Patsy on a leash.

‘Ooh,’ said Shirlene. ‘That is exactly th’ dog I am lookin’ for!’

‘This dog is taken,’ said Omer.

‘What’s its name?’

‘Patsy.’

‘Patsy! This is exactly the dog I would love to have. Look at its face.’ Shirlene stooped to pat Patsy—palm trees swayed. ‘Patsy, Patsy, I would sleep with you!’

‘She’s sleepin’ with me,’ said Omer.

Shirlene looked up and smiled. ‘Well, she is one lucky girl.’

‘Whoa,’ said Winnie. ‘I gotta get on my break.’

He was staying in the tall grass. He wouldn’t say a word, no, sir. Let them figure out the yard sale and Scrabble business, he was glad to get this thing off his hands.

‘Here you go, Father.’ Omer thumped a bag on the counter. ‘Russets and Yukon Gold.’

He examined a russet. ‘Beautiful! Prizewinning! My goodness, look at this.’ He said what people in his Mississippi childhood always said when given a worthy gift. ‘What do I owe you?’

‘Free as th’ air we breathe,’ said Omer. ‘Y’all like mashed potatoes?’

‘We do. Definitely.’

‘Drop a turnip in there. Cook it and mash it in with your potatoes. Adds a really nice flavor.’

Shirlene stared at Omer.

‘I’ve heard of doin’ that,’ she said. ‘But I never met anybody that does it. Do you use real butter?’

‘Yes, ma’am. Life is short.’

Patsy was straining at the leash and headed for the door. ‘Gotta go, Father. See you at th’ Feel Good. Patsy’s after a squirrel.’

And there went Omer.

‘Ohmigosh,’ said Shirlene. ‘Who was that?’

‘That? Ah . . .’

‘He was adorable.’ She went to the window and looked out. Omer was dashing across to the post office, Patsy in the lead. ‘Free as th’ air we breathe. That was darlin’.’

‘So, Shirlene, thanks for letting me transfer my certificate. I’ve decided what I’d like to do with it, and thank you very much, it was very generous of you.’

‘I wish you’d use it for yourself.’

‘I know, and I probably should, but I’m putting the certificate in the spring auction for the Children’s Hospital.’

‘Oh, that is so good. That is absolutely brilliant.’

‘Well, thanks,’ he said. ‘Are you spending Thanksgiving with your sister?’

‘I’m goin’ home to Bristol to see Mama and do her highlights. Who did you say that was?’

‘I apologize for not introducing you.’ Rude, indeed, but so be it. ‘That was the fellow you see in the little yellow airplane, headed south.’

‘I’ve never seen anybody headed south in a little yellow airplane.’

‘You’re probably working when he flies over.’

Shirlene gathered up her book. ‘So, when are we goin’ to have lunch with Homer?’

‘One of these days, for sure.’

Winnie waited for Shirlene’s departure before emerging from the poet’s gallery. ‘Holy smoke!’ she said, grinning. ‘You should fix them up.’

‘Not me,’ he said.

• • •

HE FOUND COOT in the storage room under the stairs, tears streaming.

‘What is it, buddy?’ He put his arm around the one who was their ‘fixture.’

‘I cain’t say.’

‘You can say it to me. I’m your friend. You’re our friend.’

‘Friend,’ said Coot. ‘F-R– . . .’ Coot looked at him, at a loss. ‘F-R– . . .’

‘I-E-,’ he said.

‘N-D.’

‘That’s it!’

‘I miss Mama.’

‘Of course.’

‘I always said she was mean as a rattler, an’ she was, but I miss ’er. She was my mama.’

They stayed under the stairs awhile. It was a good place to have a cry.

Chapter Twenty-seven

Saturday, December 1

Dear Henry,

A blessed Advent to you and Peggy and Sister!

Am writing from the bookstore to say what a wonderful Thanksgiving we had and I trust your own summoned a plenitude of grace. You sounded the best yet when we spoke.

And while we covered most of the bases, I feel the urge now to send something to greet you at the mailbox. I’m one for the cards and letters, myself, and am grateful for your faithfulness to us in that regard.

Dooley left here early on the 29th and Lace is on her way to Virginia as I write. D and L appear genuinely in love—it is a sight to see.

Actually, he had seen more than was intended.

On walking past the door to the deck, he had glanced out. They stood by the railing, wrapped in each other’s arms. He saw plainly the look on Dooley’s face, a look he had certainly never seen before. In something like slow motion, they kissed.

He had moved quickly into the kitchen, struck to the marrow by the power of that moment, a gift unwittingly captured for all time.

• • •

UP AND DOWN MAIN, an angel formed of tiny lights had been installed on every lamppost; alleluias and glorias poured forth from the sound system at the Town Hall, and ready or not, it was December first, and Christmas in Mitford was official.

• • •

HÉLÈNE PRINGLE WAS NOT ONE to let go of her notions.

Tomorrow was the first Sunday of Advent and, like the rest of the common horde, she was heading into full Christmas mode. She dropped by the bookstore on her way to the Local, toting her fold-up shopping cart.

‘Hélène, you are Catholic. You know very well that Christmas cannot be had before Advent, any more than Easter can occur in advance of Lent! Further, I must be selling, don’t you see, not lounging about in a hot suit trimmed in fake fur. We are shorthanded as it is, we cannot put an employee in the window.’

She didn’t get it. He pressed on.

‘Further still, there will be gift-wrapping to do.’ Gift-wrapping! Right up there with locusts and plagues. He was stressed about this.

‘I feel certain I can teach Coot to gift-wrap,’ she said. ‘He is surprisingly handy. And in any case, Saint Nicholas did not wear a suit, he was a bishop. He would have worn a cassock, a surplice, a stole, a cope, and a pectoral cross.’

‘With mitre and crozier, I suppose,’ he said, dry as crust.

‘That, too.’

The torment of it.

‘The mother of one of my old pupils is a marvelous seamstress. I tutored her daughter without charge for an entire year. She is willing to make you a most glorious costume—if she is provided the fabric which can be purchased for a song in Wesley.’

She appeared to be running out of steam, but no.

‘You can count on me,’ she announced, ‘to provide the sack.’

‘Ah-h,’ he said.

Hélène said something in French.

• • •

ESTHER CUNNINGHAM, now fully recovered from her stroke, was on the phone and none too happy.

‘I’ve been meanin’ to ask—do you have any idea why th’ dadblame Christmas parade happened th’ day before Thanksgivin’?’

‘Not a clue.’

‘Christmas does not come before Thanksgivin’.’

‘Maybe they’re working toward slipping it in around Halloween.’

‘I need to talk to th’ council. Just wait’ll I get over this hackin’ cough,’ she said, proceeding to hack. ‘How was th’ candy?’ she said. ‘I’m not gettin’ a good report on th’ candy.’

Lord knows, he had stepped up to the corner of Main and Wisteria just to check on this item of concern. Santa had cruised in at the end on the back of a pink Thunderbird convertible, and as far as he could tell, it was all ho-ho and no candy.

‘Um,’ he said.

‘My great-grans did not get a single piece. Fourteen great-grans scattered through th’ crowd and not one piece of candy.’

‘Lower dentist bills,’ he said.

• • •

SALES HAD BEEN BRISK, albeit with no help from a couple of people who dropped by to read the Sunday Times, now entering the ravaged state. He was totting up the numbers when Hélène jangled in with a full cart.

No rest for the wicked, and the righteous don’t need none.

‘Think of it this way, Father. Saint Nicholas carried forth God’s love by giving all his inheritance to the poor and needy. He dedicated his life to others, and was especially loving to children. We know the infant laid in the manger is almighty and supreme, now and forevermore. Saint Nicholas was but God’s hands and feet, just as you are in your time in history.’

Cease! Desist! Arrête!

‘Happy Endings could distribute sweets to the children who come to the store, and everyone who wishes could bring a small gift for the patients at Children’s Hospital! Think how many of them come from the desperate parts of our mountains, Father. And so you see—your favorite charity would even today be served by a good man born long ago in the third century. How wonderfully it all ties together.’

She was breathless with conviction.

‘How long would this . . . go on?’ he said.

‘We could start as soon as Polly gets the fabric and runs up the costume. Tout de suite! Le temps c’est de l’argent! We have no time to lose!’

‘And who is to pay for the fabric?’

She gave him an expectant look. A French look, he thought, though he had no standard for what that might be.

‘Not I,’ he said, meaning it.

He agreed to nothing in her proposal. On the other hand, her pitch had succeeded, if only in making him feel the pressure of a fast-approaching Christmas. Something must be done.

He called Hope.

She directed him to a stack of author posters under the stairs.

He turned one over and uncapped a Magic Marker.

Christmas Help Wanted

Apply Within

‘Take down the sign,’ said his wife. ‘I’ll do it. My eyes will appreciate the break. And fun—it will be fun! A mom-and-pop operation!’

‘I’d like you to gift-wrap,’ he said, wanting to nail this issue immediately.

‘I’m not terribly good at it.’

‘I am not gift-wrapping,’ he said in his pulpit voice. ‘Not with help running around.’

‘Okay, okay. I’ll gift-wrap and you’ll pack our lunches.’

‘Deal.’

‘No chicken for me, I am off chicken. And no salt on anything and no white bread, and by the way, I can’t work but one day a week. I’m painting the other days and Christmas is coming and I have lists to make.’

Lists to make! Into the backpack went a notepad; he would knock his list out tomorrow.

‘Saturday would be best for me,’ she said. ‘And no avocado, either. Too fattening.’

He mustn’t forget chocolates for Hope House and Children’s Hospital nurses. Lipstick for Louella, she was depending on him, and there was Walter, of course, who was difficult, not to mention costly, to shop for, and Katherine . . . why didn’t he keep his lists from former years and just make minor revisions annually? This had never occurred to him before.

And what would he give Dooley? And Sammy, for that matter, and Kenny, who would be leaving straightaway and could use a warm jacket, and the grans, four of them, and Coot—there must be something under the store tree for Coot—and Marcie and Hélène, of course. Store tree! When did that go up? Not anytime soon—he would put his foot down on that nonsense.

‘And no cheese or peanut butter,’ she said.

Did Hope have gift-wrapping supplies stuck somewhere, or did he need to run to Wesley? And music. He hadn’t seen any Christmas music in Hope’s stash of CDs.

How had this happened? He had planned to keep his head about him this year, and on the day prior to Advent, he had already lost it.

• • •

THE PHONE WAS RINGING as he came through the side door at five-thirty. He had put the word out to clergy in Charlotte, and bingo!—Hope was being offered the use of a carriage house, by a member at St. John’s. An early Christmas gift for certain.

Before he could drop the backpack into his desk chair, the phone bleated again.

‘On the way home from the post office,’ said Hélène, ‘I saw your sign on the door. I’ll give you Saturdays through Christmas, Father. I can certainly do that much.’

He had forgotten to take the sign down, and was getting what he asked for—help. Very likely, he’d also be getting a dose of Grieg that would last well into the afterlife.

• • •

‘I HAVE A GREAT IDEA,’ she said, climbing into bed.

‘Do we have to do great ideas?’ He had barely managed to assemble their Advent wreath on the coffee table in the study; he was beat.

‘It can wait,’ she said, turning out the lamp on her side. She gave him a kiss. He took her hand and prayed their old evening prayer, as worn as the velveteen of the fabled rabbit. ‘. . . the busy world is hushed and the fever of life is over, and our work is done. In thy mercy, grant us a safe lodging and a holy rest and peace at the last . . .’

‘I love you,’ she said.

‘Love you back.’

The light from the streetlamp shimmered through the leaves of the maple and diffused itself in their draperies. They would be going out to Meadowgate in the morning and joining Hal and Marge at their small church in the country . . .

‘I’m wide awake,’ he said.

‘Me, too.’

‘What is your great idea?’

‘The Nativity scene you restored for me. Why don’t we share it this year? It’s so beautiful; it would give joy to everyone who sees it.’

‘But how?’

‘It would be perfect in the window at Happy Endings.’

‘We’ve been talking about using the window.’ He had by no means consented to Hélène’s elaborate scheme, and yet . . . ‘There may be dibs on that window.’

‘Yes, but there are two windows.’

He’d never thought about the other window, which was filled with freestanding bookcases. Fiction authors K through P, to be exact.

‘We could move the bookcases out,’ she said, ‘and put them in the Poetry section. There’s room back there if you move the wing chairs and the table and the rubber plant to the front.’

His peaceful days at the bookstore were over. C’est la vie.

• • •

ON TUESDAY, Coot learned to gift-wrap. Dealing with the Scotch tape, Hélène said, had given pause, but it all came around in the end. There were many rolls of green paper under the stairs; as for bows, they wouldn’t do anything fancy—a strand of raffia tied simply, with a red and green sticker which she had found at the drugstore. Would he be so kind as to help her write the store name on the blank stickers? She had bought several packages out of her own funds and it all made a very smart presentation. Coot had taken a sample over to Hope, who called Hélène to pronounce it très charmant, and insisted Hélène reimburse herself.

He seemed to remember Hélène as studious, shy, possibly even timid.

What had happened?

What was the matter with people?

• • •

WORD WAS ON THE STREET that Father Brad had wrapped up a two-bedroom rental house on the ridge, with a view ‘to die for’ and a heated garage, always handy in bad weather and, one hoped, a fairly decent place to winter over the gardenias.

• • •

THOUGH HE HAD NOT AGREED to anything, Hélène and Marcie conducted a meeting early on Thursday. Saturdays would be the store’s busiest days, they concluded, so that’s when the Saint Nicholas business should happen.

There were but two Saturdays to go, since they couldn’t make the one upcoming. What would the fabric cost? Hélène had roughly calculated the yardage in three different fabrics and was horrified by the reality of this scheme. Two hundred and fifty dollars at the discount store, plus tax.

‘Be sure to make it one size fits all,’ he said.

There was a further challenge. What to do about the beard?

‘You can probably get a beard from Mitford School,’ Winnie said, ‘if it’s not in use. They do plays all th’ time.’

‘Th’ Santy in th’ Christmas parade had a beard,’ said Coot.

‘Gone back to th’ rental company in Atlanta,’ said Marcie.

Who would seek and find the beard?

They looked at him. He adjusted his glasses and looked back, mute.

And who would be Saint Nick? Hélène declared she would do it herself. ‘Si les choses se gâtent!’ she said, loosely meaning, ‘If push came to shove.’

‘People are nutty as fruitcakes,’ he told his wife.

‘Very seasonal,’ she said.

• • •

ON FRIDAY AFTERNOON, he learned, Hélène had gotten in her car, manufactured in a remote year, and careened down the mountain to a community theater said to own an assortment of beards.

He had once careened down the mountain with Hélène Pringle and lived to tell it. He had learned all too late that her brakes had gone bad and there were no funds to get them replaced. It was a thrill ride that money couldn’t buy, second only to flying with Omer in a taildragger and eyeing the scenery through a hole in the floorboard.

‘Here’s what somebody needs to do,’ he said to Winnie when he stopped by Sweet Stuff after the bank. ‘Find a person who has an actual beard. The woods are full of them back in the coves and hollers. I guarantee it.’

‘I’m not goin’ back in there,’ said Winnie. ‘No way. That’s where all my cousins live.’

‘In any case, there’s the answer.’

‘I cannot abide facial hair,’ said Winnie. ‘I’m makin’ donut holes for th’ big day, an’ that’s it for me.’

The word blew along Main like a paper napkin from a fast-food takeout. On Saturdays, starting next week, Abe would be offering hot cider. The Woolen Shop would set out ginger snaps. Winnie and Thomas were giving away donut holes, two to a customer. And the bookstore would be putting on some kind of a show.

• • •

COOT HAD GONE to their house and cleaned up the Nativity scene.

The figures would be placed in the window right away, in an order suggesting the coming birth of the the Bright and Morning Star.

First, the Virgin Mary and Joseph at the empty manger, seven sheep, a donkey, a cow, two members of the heavenly host, and a stable which someone had given anonymously the year he restored the figures.

After a few days, the wise men would be introduced into the fringes of the scene, looking none the worse for having tossed around for a couple of years on the humps of camels.

What a lot of rubble it had all been when he’d found the twentysomething pieces at Andrew’s antique shop. Orange had been the operative color—skin, robes, even the camel. Andrew wondered why he’d bought the conglomeration, which took up costly container space on its way across the Pond from England. ‘A reckless purchase!’ said Andrew.

In buying it from Andrew, he had been uncharacteristically reckless, himself. Did he know how to restore plaster fingers and noses? No. Or how to paint realistic skin tones? No. Or what color anything should be, especially the wings of angels? Not a clue. He had solved this by consulting old Christmas cards and books showing crèche figures. As for the wings of angels, obviously they could be any color the artist chose to make them.

He had been intoxicated by the act of bringing each figure to life, thanks to help from Andrew and Fred. Dooley had painted the camel and its saddle blankets, and was also caught up in the thrill. It had been a huge challenge, but joy had overwhelmed fear, and the miracle had been accomplished.

On Friday night, he and Harley transported the whole caboodle in the truck bed, and Cynthia came along to give a hand. They rolled the bookcases into the Poetry section, brought up the chairs, restationed the rubber plant.

Fiercely cold tonight. Not a soul on the street. They worked quickly. Harley toted in a bale of straw and let it loose in the window. The lighting, seldom used in this area and acting as the star, was pretty good.

They moved the figures around. That some of them were nearly two feet tall was useful in the large space.

The Virgin Mother to the left of the empty manger, Joseph to the right. Three sheep standing, four lying in the straw, along with the old shepherd he had learned to love as he’d painted the solemn face.

They stepped outside and looked in.

‘Goose bumps,’ said Cynthia.

‘Where’s th’ baby Jesus at?’ said Harley.

‘He arrives on Christmas morning. Advent is a time of waiting.’

‘People’ll be lookin’ f’r th’ baby Jesus.’

‘And there,’ he said, happy, ‘is the whole point.’

• • •

ON SATURDAY, there were more than a few noses pressed to the Nativity window, and more than a few of the curious came in to buy a book or two or three.

Marcie and Hélène convened at eleven, Winnie included.

‘How’s your mother?’ he asked Marcie.

‘Drivin’ me crazy.’

Shirlene stopped by for a quick coffee. Maybe there was a Caftan-of-the-Month Club . . .

‘How’s business?’ he asked Shirlene.

‘On a scale of one to ten, a six. You would not believe who just walked out with a Boca.’

‘Who?’

‘I’ll let it be a surprise!’ said Shirlene. ‘When do I get to meet Homer?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘I don’t know how I’m ever goin’ to meet somebody. I guess he’ll just have to fall out of th’ sky.’

He had noted over the years that a good many single women counted on this very phenomenon, possibly influenced by what the Lord himself allowed through his servant James, ‘All good and perfect gifts come down from the Father above.’

‘The way you find a husband,’ said Winnie, ‘is you’ve got to get out there.’

‘Winnie met Thomas on a cruise,’ he said.

‘I’ve always heard you can’t meet men on a cruise,’ said Shirlene. ‘Single men do not go on cruises.’

Winnie beamed. ‘Thomas wasn’t a passenger, he was in th’ kitchen, bakin’. Which I would consider totally out of th’ sky.’