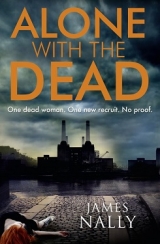

Текст книги "Alone with the Dead"

Автор книги: James Nally

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 22 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 9 страниц]

The cop took a long hard look at me: ‘He was pronounced dead at the scene, son. Why do you ask?’

I told myself there must be a logical explanation – must be … must be. My head swooned. ‘Donal, love, are you okay?’ sounded Mum’s voice as last night’s blinding lights returned, slashing at my vision.

I ignored the panic because I couldn’t take any more: I let myself sink down, down until all those hot white needles of hospital light went away.

Chapter 3

Clapham Junction

Tuesday, July 2, 1991; 08:15

I marched back to Sangora Road, unable to banish the squalid thought that Marion Ryan’s murder represented a gilt-edged career opportunity.

My two-year probation as a beat Constable was almost complete. In a few weeks, I’d be eligible for promotion to Acting Detective Constable. There were more beat officers than Acting DC positions: competition was fierce.

Later today, I was due to make a statement to the investigating team. By re-examining the murder scene, perhaps I could offer up a few fresh insights or theories; make a good impression. I needed a senior officer to spot me and think that I was worthy of championing; to take me under his or her wing.

I took a short cut across Wandsworth Common, ignoring the tarmac pathways. London’s green spaces seemed so orderly and controlled to me: the opposite of nature. It’s a wonder there weren’t signs saying, ‘Keep Off The Grass’. As I trod the dewy sward, I let my mind drift off-road too. After this morning’s chilling encounter, I needed to open myself up to all possibilities. It was time for a logic amnesty.

One fact felt indisputable: Marion’s attack on me hadn’t been a dream. When she came to me in the flat, I’d been wide awake, albeit a bit pissed. I could see and hear everything around her in the streetlight orange tinge – the furniture, the traffic outside, the slamming door. I’d felt her breath on my face.

And, three years earlier, I’d felt Meehan’s cold, gloved hands strangling my throat.

I didn’t believe in ghosts, spirits, religion, the supernatural or any of that stuff. But the most obvious explanation for what happened last night – however crazy – was that the spirit or ghost of Marion Ryan had come to me. A few hours earlier, I’d been physically close to her recently murdered body. Three years ago, Meehan came to me at Tullamore General Hospital as I slept upstairs from the basement morgue hosting his fresh corpse. I had to ask the question: did my proximity to a body that had just met a violent death somehow open up a telepathic pathway between us? And if so, what were their spirits trying to tell me? And how could they get inside me?

The naked malevolence of Meehan’s assault didn’t seem to say much, apart from he wished me harm. But while Marion’s attack felt every bit as threatening, there was something about the encounter that made me think she had been trying to tell me something. That slamming door. What did it mean? I had to get to Sangora Road and see if something snagged on my mind.

As the grass of the Common gave way to concrete, a rancid stench invaded my senses. I checked both soles, located the soft wet dog shit wedged between the grips of my left shoe and declared the logic amnesty over.

As I rubbed my shoe against a grass verge, I tried to come up with a more believable solution. Meehan throttling me had been a graphic hallucination. After all, I’d just ingested enough tranquilliser to poleaxe a sadhu. Marion’s apparition was a result of post-traumatic stress – or post-traumatic Shiraz, as Aidan put it. Seeing her wound-covered body last night had obviously affected me more than I’d realised.

Sangora Road had already recovered its leafy, anonymous poise. On one side, a road sweeper clanked along grudgingly. On the other, a couple of suits made breakneck progress towards Clapham Junction train station. Ahead of them, a racket of rotund school kids swore loudly, smoked and spat. I wondered what Tullamore’s own Jesuit terrorist Father Devlin would give for ten minutes in a locked room with that lot, and how much I’d pay to watch.

Across the road from number 21, the press pack swarmed, keen as hyenas. I counted nine still camera lenses, presumably all jostling for the same shot. I couldn’t help thinking: what a waste.

As I cast them my most contemptuous glare, a morose Northern voice stopped me in my tracks.

‘Where do you think you’re going?’

Clive ‘Overtime’ Hunt was one of the less offensive nicknames earned by my beat partner over the years. Colleagues would plead with me: ‘Find out what he does with all the money?’ He simply couldn’t say no to overtime and must have worked at least seventy hours a week, every week.

‘You did go home at some stage, Clive?’

‘Oh yeah. I got back here at eight this morning. Easiest gig going this, standing at a door.’

‘Exciting too,’ I said, ‘so what’s been happening?’

‘They removed the body about two hours ago. Forensics are still working, so don’t cross the tape, obviously,’ he drawled, the irritating tit.

He unlocked the internal door to the flat, then almost ceremoniously pulled it open.

‘Thanks, Clive,’ I said, ‘but that’s really not necessary.’

‘Oh but it is,’ he said, ‘it’s one of those fire doors, spring-loaded to close itself, except it’s been sprung too tight.’

‘Oh,’ I said, putting my palm against the half-open door. Just like last night, it pressed back hard.

PC Know-It-All’s furniture-and-fittings briefing wasn’t over yet: ‘Clever things, these fire doors; at a certain temperature they expand and seal the gaps, blocking out flames and, even more important, smoke. Smoke inhalation is actually the biggest killer, you know.’

‘Fascinating,’ I said, turning on the first step, then letting the door go so it slammed behind me.

I imagined Marion coming up these stairs. She had her post, keys, handbag and jacket over her arm. Whoever killed her was either in the flat already, or had met her at the front door as she returned from work. The idea that someone was already inside felt less plausible – there were no signs of a break-in. Only she and Peter had keys. If she let her killer in, then she must have known him.

Ninety-eight per cent of murder victims know their killer.

He followed her up the stairs, launching his attack from behind. But if it was Peter, why would he stab her to death on the landing? He could have killed her in any of the rooms, in a variety of ways, at any time of the day or night, silently and without leaving evidence or causing a commotion. It just didn’t stack up. Unless it had been a crime of passion: one of them had been having an affair, confronted the other. Peter had lashed out in a blind rage. It’s always the man, isn’t it?

My mind turned to Peter and Karen finding the body. I imagined myself as Peter coming up the stairs. I was about the same height – five ten – so I stopped at the spot where he would have seen Marion’s body on the landing.

Karen wouldn’t have seen the body yet. She was five foot four, tops, and must have been at least a step below Peter, if not two. He called Marion’s name and went to her body.

Karen told me she’d been the one to check for signs of life. That’s how she got Marion’s blood on her hands. Had Peter made any sort of check first? If not, then why not? Did he already know she was dead? I couldn’t be sure if this meant anything, but made a mental note just in case. I’d mention it later to the investigating officers, show them I had solid detective potential.

I walked up to the police tape and exchanged a nod with the forensics who were tweezing every inch of the landing.

There seemed to be very little blood on the carpet and walls, considering all the wounds Marion had suffered. Either she had died quickly – blood stops flowing when you expire – or most of her wounds were superficial. I wondered if I’d get a look at the pathology report.

The window on the landing overlooked a flat roof below. Someone could have climbed onto that roof and scrabbled up the rooftiles to this window. I unfastened the latch and opened it as far as it could go: about four inches. It looked new and hadn’t been forced. The killer didn’t get in through here.

Cool air rushed my face, voodoo lurking in its slipstream.

After three hours, they close the window, to ensure that the spirit doesn’t return.

She usually gets home before six … we got back just after nine …

Had I been standing here as her spirit returned, hungry for vengeance?

My eyes followed the blood streaks along the wall. I wondered what would happen to the flat now. Surely Peter could never come back to live here, guilty or not. Who would paint over the blood? Would future prospective tenants be told of the horror that had taken place, here on these stairs?

The flat door below heaved open, followed by the sound of someone labouring up the stairs.

‘You could probably get this for a hell of a good price now,’ panted Clive, as if he’d read my mind, ‘be a smashing first-time buy.’

‘Could you actually live here though? Every time you’d come up these stairs, you’d be thinking someone died here, horribly.’

‘I’d leave the blood and charge people for a look.’

‘Jesus.’

We both stared for a moment in silence at the spattered remnants of Marion Ryan’s final seconds, the red colour already browning.

‘What do you think then?’ said Clive.

‘Well, if I’ve learned anything over the past two years, it’s that crimes tend to be either personal or opportunistic,’ I replied. ‘This was definitely personal, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Well, if I’ve learned anything over the past twenty years, it’s to keep an open mind.’

I could feel his look. ‘Tell them what you think today, but don’t be too opinionated. They won’t respect that.’

I nodded.

‘You’re a PC, they’ll see you as nothing more than a street butler; present when needed, otherwise invisible. Know your place, son.’

‘Got it,’ I said, the words, ‘cannon fodder’ drifting through my mind.

I’d be fucked if I’d know my place in Clive’s class system. England, the world’s only courteous tyranny.

Marion lay on the waiting room table at Clapham police station, beaming and radiant. The photo of her and Peter on a recent night out dominated the Standard’s front page. Head tilted into Peter’s chest, her smiling blue eyes oozed contentment. Her hair – big and curly à la Julia Roberts’ in Pretty Woman – had an almost other-worldly crimson glow which seemed to drain all the blood from her milk-white skin. Her high cheekbones and freckled nose brought Eve to mind. But Marion’s features – nose, chin, eyebrows, forehead – were more pronounced: she was striking, rather than pretty. Juxtaposed with her strong face was a smile so coy, kind and natural that it lit up the page, casting a sad shadow across my chest. I forced my eyes away from the photo to the accompanying report. I needed to expunge all emotion, stick to the facts.

London-born of Irish parents, twenty-three-year-old Marion O’Leary met Peter Ryan in North London’s Archway Tavern when she was seventeen. Peter, from Mayo, had been her only boyfriend. They got married in Ireland last year.

I’d met lots of second-generation Irish in London, like Marion. Invariably, they held a romanticised view of ‘the old country’, usually based on a handful of childhood holidays, and family propaganda. Most had been indoctrinated in Irish culture since birth. I bet Marion attended the local Catholic school and church. She would have taken First Holy Communion and Irish dancing classes and celebrated Paddy’s Day more than I ever did.

She would have socialised in Irish pubs and clubs, hoping to meet a dashing Irishman who’d whisk her off her feet. They’d marry and move to a bungalow in the west of Ireland, where their kids – red-haired, freckled and plentiful – would run about barefoot and gleeful, stopping only to say the Angelus together at six o’clock each evening.

We first-generation Irish had news for these ‘plastic Paddies’, some quite old news at that: romantic Ireland’s dead and gone.

I couldn’t help assuming that Marion had bought wholesale into her parents’ dream. Marrying her first proper boyfriend made me suspect she was trusting, idealistic, a little naïve – not the type to have an affair, or to let a stranger into her flat. So how then did Peter fit into all of this? Why would he kill her? Maybe he was having an affair and couldn’t bring himself to tell her. After all, most Irishmen will do anything to avoid a scene. Or she confronted him about it and he flipped. But surely he didn’t hack his own wife to death on the stairs with a knife, then go back to work? That didn’t stack up.

I was mentally listing the most compelling reasons why this crime had to be domestic when I leapt at the sound of my own name. The uniformed officer led me out of the waiting room, down a long corridor, through a pair of electronic security doors, along another corridor, then left into an interview suite. I sat there in airless isolation for what seemed like an age, a hothouse mushroom incubating on stale smoke and sweat. I couldn’t understand why I felt so nervous.

Two middle-aged detectives finally strolled in, coffee cups full, fags on, fresh smoke sweetening the fusty air.

‘I’m DS Barratt, this is Inspector McStay,’ said the taller one, letting his superior sit first.

I talked through everything that happened last night, throwing in my theories for good measure. When I wrapped up, they told me to write it all down in a statement, minus the theories. As I wrote, I repeated my assertion that Marion must have known her killer.

‘Thank you, PC,’ snapped McStay, emphasising my job title, ‘the Big Dogs are all over it now.’

I went on, ‘She clearly let her killer in. She knew him or her well enough to pick up her post.’

‘Who would be your prime suspect then, Lynch?’ asked Barratt, mildly amused.

‘I’d have to start with the husband, Peter. Was he playing away? Did she find out? Has he got a history of violence? It doesn’t usually come out of the blue, does it? I’ve read about a lot of other cases and it normally escalates from domestic abuse. Peter is where I’d start.’

‘Good theory,’ said Barratt, scanning my statement, ‘we’re bringing him in as we speak. He’s going to talk to the press, appeal for help to find her killer.’

He looked up at me: ‘Alongside Mr and Mrs O’Leary, Marion’s mum and dad.’

I tried not to look confused.

McStay seized the moment: ‘Peter is staying with Marion’s parents. Do you think they’d have him living in their own home if they thought for one second he could have been capable of killing their daughter?’

He got up, strode to the door and flung it open: ‘Better get back out there, son. Those bike thieves won’t catch themselves.’

As I made my way back out of Clapham police station, I recognised the rodent-like scurrying of her majesty’s press.

Amid the yapping throng surged my brother Fintan, now Deputy Crime Correspondent of the London-based Sunday News. If the Chief Crime Correspondent didn’t have a pension plan, he needed to get one, soon.

I followed the hordes into a large conference room, taking a seat near the exit. I wanted to see Peter explain himself. I wanted to see if his in-laws exhibited any kind of suspicion.

Within seconds, my identity had become a talking point among a group of photographers. Fintan joined their chat, clocked me and scuttled over, beaming.

‘I hear you found the body?’ he roared, confirming he’d no shame.

‘Jesus, would you not have some decorum, Fintan.’

‘Maybe we can help each other.’

‘I’m not talking to you.’

‘Come on, Donal.’

‘You know I can’t tell you anything.’

‘Fine. Fine. I wonder though, is a PC like you supposed to be nosing around a cordoned-off crime scene after the case has been taken over by a senior detective?’

A red warning light pinged on in my brain.

‘Well I am a police officer, Fintan. That’s pretty much what I do these days.’

‘Oh okay. It’s just … ah nothing, doesn’t matter.’

‘What?’

‘Well, you see that guy over there?’ he said, pointing to a large man cradling a cannon-sized Canon camera.

‘He’s a snapper, from the Standard.’

‘Bully for him.’

‘He said he took your photo earlier today, as you came out of the house on Sangora Road.’

My heart set off on a gallop.

‘And guess what? His editor likes it. Donal, you’re going to be on the front page of the Evening Standard. Imagine that! You on the front page? I’ll send a copy to Daddy. He’ll be made up.’

‘Oh Jesus,’ I sighed.

Fintan guffawed: ‘You, a lowly PC, sneaking around a live crime scene without DS Glenn’s permission? He’s a real hard ass, Donal. He’ll go apeshit.’

I’d already pissed off DS Glenn – the officer in charge of the case – during our first meeting last night.

‘They can’t just use my picture. I have rights.’

‘Afraid not, bro. It’s a public place. He can snap what he likes. Would you like me to have a word with him?’

‘Please,’ I sighed.

Of course I’d never know if any of this was true. Fintan spent his entire life finagling leverage.

He returned in less than a minute. ‘Sorted,’ he said, ‘you can relax. I told him you’re on an undercover job at the minute, and this photo could blow your cover. He’s on the phone to his picture editor now.’

He sat next to me. ‘You’ve got to be more careful, Donal. Seriously, someone like Glenn could have you consigned to uniform for life.’

‘Thanks,’ I said, wondering if that’s what happened to PC Clive Overtime.

‘Don’t mention it. You can buy me a nice pork salad for lunch.’

DS Glenn entered the room through a side door, followed by a bearded man in an ancient tweed jacket and a haunted, ashen Peter. Ten feet behind, clinging together, were a middle-aged couple who needed no introduction. Cameras whirred, clicked and sprayed like slo-mo machine guns.

‘Her people are from Kilkenny,’ said Fintan, shouting over the camera cacophony.

‘Who’s the tweed?’

‘Professor Richards, a forensic psychologist. He’ll be observing Peter, you know, his body language and all that, see if he’s lying.’

‘He’ll be able to tell?’

‘Glenn swears by him.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘It’s my job! Happily for me, you cops gossip like fishwives.’

Richards sat at the extreme right-hand chair at the top table. Glenn led Peter to the seat next to the Professor then sat Marion’s parents to the left, taking centre stage himself.

He explained who he was, then introduced the Prof, Peter, and Marion’s mum and dad, Mary and John.

The snappers continued to hose them down. Glenn pleaded for restraint. They eased off for fully two seconds.

As Glenn ran through the indisputable facts of the case, I took a good look at Peter, slumped, fumbling busily with his fingers, like a widow with rosary beads.

He looked impressive, handsome, if somewhat vain and self-satisfied. He had an unfortunate perma-smirk which had probably earned him more slaps in life than hugs. His slicked-back auburn hair owed much to Don Johnson and cement-grade gel. He could have been a lower-league professional footballer or a wedding DJ with a name like Dale or Barry.

My eyes drifted over to Mary and John. Mary embodied every Irish mum I’d ever known: small, tough, thick grey hair fixed fast into position, a fighter’s chin. Her face puce, her body bent with grief, she clenched rosary beads in one palm and John’s hand in the other. She didn’t look up from the table once.

I thought about my own mum. I really needed to make that call.

Marion’s dad John sat bolt upright like a guard dog, surveying the room, defending his family, defying the pain. I’d dealt with the parents of murdered people before. They usually split up in the end. The mum always blames the dad, even when she doesn’t want to. It must be hard-wired deep within mothers that the father’s primary role is to protect the family. Even in cases where the dad couldn’t possibly have done anything to save the child – like this – that sense of blame is there. I hoped John and Mary would make it.

Glenn summarised: ‘We would like to appeal to anyone who lives, works or who happened to be in the Clapham Junction area between five and seven p.m. last Monday evening to please call us with any information that may help us find this killer. It doesn’t matter how minor or trivial it may seem, if you saw anything unusual or suspicious, please call us. Finally, I’d like to warn people in London, particularly lone women, to be vigilant and alert.’

It was Peter’s turn to speak. He hadn’t written anything down.

He looked directly at a TV camera and said: ‘I’d like to ask the public to please help find Marion’s killer. Whoever did this is not human … they have to be caught …’ His already high voice reached castrato pitch, before cracking. He squeezed his eyes shut, then his head fell and he sobbed. The cameras swarmed in for the kill.

No one noticed Mary sobbing too, or John squeezing her hand.

Questions rained in from the floor: ‘Are there fears that a maniac is targeting women in their homes?’

Glenn: ‘I’ve nothing to add.’

‘Are you linking this to other crimes?’

Glenn: ‘As part of any investigation, we look for connections to similar crimes.’

Then Fintan got to his feet: ‘Is 21 Sangora Road known to police?’

John glared over. ‘No,’ he roared and I felt myself shrivel.

‘No more questions,’ shouted Glenn, summoning Peter to his feet. As Glenn led him out, Mary and John didn’t look his way once.

‘I’m off to find a phone,’ said Fintan.

‘Grand. See you in Frank’s?’

‘Yeah, great. Twenty minutes.’