Текст книги "The End Is Nigh"

Автор книги: Jack McDevitt

Соавторы: Nancy Kress

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Нэнси

Кресс

Джек

Макдевитт

Джейми

Форд

Джон

Джозеф

Адамс

Сара

Ланган

Дезирина

Боскович

Тананарив

Дью

Уилл

Макинтош

Паоло

Бачигалупи

Тобиас

Бакелл

Дэвид

Веллингтон

Чарли

Джейн

Кен

Лю

Шеннон

Макгвайр

Robin

Wasserman

Хью

Хауи

Джонатан

Мэйберри

Скотт

Сиглер

Matthew

Mather

Jake

Kerr

Annie

Bellet

Megan

Arkenberg

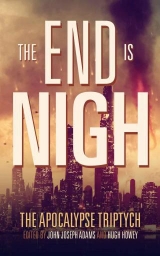

The End Is Nigh

Famine. Death. War. Pestilence. These are the harbingers of the biblical apocalypse, of the End of the World. In science fiction, the end is triggered by less figurative means: nuclear holocaust, biological warfare/pandemic, ecological disaster, or cosmological cataclysm.

But before any catastrophe, there are people who see it coming. During, there are heroes who fight against it. And after, there are the survivors who persevere and try to rebuild. THE APOCALYPSE TRIPTYCH will tell their stories.

Edited by acclaimed anthologist John Joseph Adams and bestselling author Hugh Howey, THE APOCALYPSE TRIPTYCH is a series of three anthologies of apocalyptic fiction. THE END IS NIGH focuses on life before the apocalypse. THE END IS NOW turns its attention to life during the apocalypse. And THE END HAS COME focuses on life after the apocalypse.

Volume one of The Apocalypse Triptych, THE END IS NIGH, features all-new, never-before-published works by Hugh Howey, Paolo Bacigalupi, Jamie Ford, Seanan McGuire, Tananarive Due, Jonathan Maberry, Scott Sigler, Robin Wasserman, Nancy Kress, Charlie Jane Anders, Ken Liu, and many others.

Post-apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that have already burned. Apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that are burning. THE END IS NIGH is about the match.

2014

en

en

Stas

Bushuev

Xitsa

FB Tools, sed, VIM, Far, asciidoc+fb2 backend

2014-04-02

Xitsa-111A-2AC8-F680-5B6967491F15

1.0

John Joseph Adams – INTRODUCTION

“It was a pleasure to burn. It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.”

Fahrenheit 451

Ray Bradbury

I met Hugh Howey at the World Science Fiction Convention in 2012. He was a fan of my post-apocalyptic anthology

Wastelands

, and I was a fan of his post-apocalyptic novel

Wool

. Around that time, I was toying with the notion of editing collaborative anthologies to help my books reach new audiences. So given our shared love of all things apocalyptic—and how well we hit it off in person—I suggested that Hugh and I co-edit an anthology of post-apocalyptic fiction. Obviously, since his name is on the cover beside mine, Hugh said yes.

As I began researching titles for the book, I came across the phrase “The End is Nigh”—that ubiquitous, ominous proclamation shouted by sandwich-board-wearing doomsday prophets. At first, I discarded it; after all, you can’t very well call an anthology of post-apocalyptic fiction

The End is Nigh

–in post-apocalyptic fiction the end isn’t

nigh

, it’s

already happened

!

But what about an anthology that explored life

before

the apocalypse? Plenty of anthologies deal with the apocalypse in some form or another, but I couldn’t think of a single one that focused on the events leading up to the world’s destruction. And what could be more full of drama and excitement than stories where the characters can actually see the end of the world coming?

At this point I felt like I was really onto something. But while I love apocalyptic fiction in general, my real love has always been post-apocalypse fiction in particular, so I was loathe to give up on my idea of doing an anthology specifically focused on that.

That’s when it hit me.

What if, instead of just editing a

single

anthology, we published a

series

of anthologies, each exploring a different facet of the apocalypse?

And so The Apocalypse Triptych was born. Volume one,

The End is Nigh

, contains stories that take place

just

before

the apocalypse. Volume two,

The End is Now

, will focus on stories that take place

during

the apocalypse. And volume three,

The End Has Come

, will feature stories that explore life

after

the apocalypse.

But we were not content to merely assemble a triptych of anthologies; we also wanted

story triptychs

as well. So when we recruited authors for this project, we encouraged them to consider writing not just one story for us, but

one story for each volume

, and connecting them so that the reader gets a series of mini-triptychs

within

The Apocalypse Triptych. Not everyone could commit to writing stories for all three volumes, but the vast majority of our authors did, so most of the stories that appear in this volume will also have sequels or companion stories in volumes two and three. Each story will stand on its own merits, but if you read all three volumes, the idea is that your reading experience will be greater than the sum of its parts.

In traditional publishing, this kind of wild idea—publishing not just a single anthology, but a

trio

of anthologies with interconnected stories—would be all but impossible, so it was just as well that Hugh and I had already decided to self-publish. But the notion that this was something that traditional publishing wouldn’t—or couldn’t—do made the experiment even more compelling, and made working on this project even more exciting.

Post-apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that have already burned. Apocalyptic fiction is about worlds that are burning.

The End is Nigh

is about the match.

Robin Wasserman – THE BALM AND THE WOUND

Here’s how it works in my business: First, you pick a date—your show-offs will go for something flashy, October 31 or New Year’s Eve, but you ask me, pin the tail on the calendar works just as well and a random Tuesday in August carries that extra whiff of authenticity. Then you drum up some visions of hellfire, a smorgasbord of catastrophe—earthquake, skull-faced horsemen sowing flame and famine in their wake, enough death and destruction to make your average believer cream his pants—and that’s when you toss out the life-preserver, the get-out-of-apocalypse-free card. Do not pass

go

, do not collect $200, do not get consumed by the lake of righteous fire, go directly to heaven on a wing and a prayer and a small contribution to the cause, specifically the totality of your belongings and life savings, 401Ks and IRAs—for obvious reasons—included.

Here’s how it’s supposed to work in my business: You tuck that money away for safe keeping, preferably in a bank headquartered in a non-extradition country, await the end days with clasped hands and kumbayas, and then, when the sun rises on an impossible morning, oh, you praise the Lord for hearing your prayers and offering a last minute reprieve, you go ahead and praise yourself for out-arguing Abraham and saving your modern day Sodom and Gomorrah, and let’s all give thanks for living to pray another day, even if we live in bankruptcy court.

If you don’t have the juice to pull that one off, there’s always the mulligan—

oopsy daisy, misread the signs, ignored the morning star, overlooked the rotational angle of Saturn, forgot to carry the one, my bad

. Dicey, but better than drinking the Kool-Aid—and if you can’t envision a Great Beyond worse than prison, you might be in the wrong line of work. You do your job right, by the time the fog clears and the pitchforks and torches hit your doorstep, you’re long gone, burning your way through those lifetimes of pinched pennies one piña colada at a time.

Like I said: Supposed to.

I’m a man who likes a back-up plan, a worst-case-scenario fix for every contingency, a bug-out route in case anything goes wrong. Never occurred to me to plan for being right.

The signs

are bullshit. Have to be. You know who “read” the signs? Pick your poison: Nostradamus. Jesus Christ. Jim Jones, Martin Luther, the whole Mayan civilization. Every flim-flam man from Cotton Mather to Uncle Sam. And every single one of them screwed the pooch. Then, somehow, along comes me. You know what they say about those million monkeys banging away on their million typewriters until one of them slams out

Hamlet

?

Just call me Will.

• • • •

Hilary dumped the kid five days after I made the prophecy, nine months before the end of the world. I remember, because by that point the Children had rigged up the calendar, a blinking LCD screen hanging over the altar to keep them constantly apprised of the time they had left. Nine months had seemed an auspicious period—long enough for the kind of slow burn panic that empties wallets but stops short of bullets to the brain, brief enough that I could keep smiling and stroking the Children of Abraham without letting slip that I wanted to throttle every insipidly trusting last one of them. But Hilary tracking me down had me questioning the timeframe, and not just because she dumped her stringy ten-year-old in my lap and took off for greener and presumably coke-ier, pastures.

I’d only been Abraham Walsh, né none of your concern, for the last five years, and before that Abraham Cleaver, and before

that

, back in the days when Hilary had decided to fuck with her parents by fucking the itinerant faith healer, Abraham Brady. If a headcase like her had managed to track me through three names, ten years, and twelve states, who knew how many cops, parishioners, shotgun-toting fathers or snot-dripping toddlers might have picked up the trail?

I had a good thing going in Pittstown, had for the last three years. The Children of Abraham had picked up about forty families and, thanks in large part to the penitent auto-parts mogul Clark Jeffries, had cobbled together some nice digs: a church, a few houses, a gated estate complete with indoor pool. Unfortunately, Clark Jeffries’ efforts to buy himself into heaven—not to mention his attempt to paper over two decades of embezzlement and hookers—didn’t extend to forking over the land deeds or any appreciable fraction of his ill-gotten gains. Always a borrower and a lender be, that was Clark’s way. Donations were for suckers.

We weren’t a growth operation—proselytizing only gets you the wrong kind of attention—and so we didn’t go in for fancy costumes or banging cymbals in airports. Tacky. None of that polygamy stuff either, not if you wanted to keep under the radar, and definitely not if experience had taught you that one wife was already one too many. The Children were a pacific and obedient bunch, and even if it got exhausting at times, playing God’s sucker so I could sucker them, the sheets were thousand thread count and there was a hot tub behind the indoor pool. Better than working for a living, especially eight months and twenty-six days from retirement. Then in walks Hilary Whatshername and the apparent fruit of my loom, Judgment Day come early.

“And what do I know about kids?” I said.

“But you’ve got so many Children, Father Abraham.” It was her best look: wide-eyed innocent with a soupçon of irony. It was the reason I’d kept her around for all those months in the first place, even though she’d seen through the big tent act from the start and could have set her daddy and his country club buddies at me on a whim. At twenty-five, she’d nearly managed to pass as a teenager; a decade later, she’d have had trouble persuading a mark she was under forty. But even with sun-spots, a muffin-top, and the ghost of a moustache, there was still a certain sex appeal there—like a stripper who’s hung up her thong but still knows how to shimmy, exuding an air of possibility, a slim hope that at any moment, the clothes might come off. “What’s one more?” she asked.

“Come the fuck on.”

“You’ll get the hang of it,” she said. “Probably.”

“He’s your

kid

,” I tried. “You want to bet on probably?”

“Better you than my parents. Better anyone than me.”

The kid didn’t say anything. We were sequestered in my office, where Hilary had settled herself onto the leather couch and kicked her feet up on the Danish modern like she owned the place. A cigarette dangled from her lips that would, knowing Hil, soon be stubbed out on the teak, leaving behind a small but permanent scar, her very own

Hilary was here

. Which I wouldn’t have begrudged her if she hadn’t been leaving so much else behind.

The kid, on the other hand, was still standing at attention, hands clasped before him, church-style, his glance not bothering to stray toward any of the room’s curiosities, the titanium safe or the shrine with its portrait of me (a substantially less flab-faced and balding me) in the thick gold frame. Just beyond the door, in the veloured ante-room, my Children waited, no doubt, with ears pressed to the wall, ostensibly to ensure that this wasn’t some kind of clever assassination attempt, likely hoping it was more of a holy visitation, Mary and overgrown Baby Jesus come to make their pre-apocalyptic crèche complete. Meanwhile here was this kid, center of the action, eyes glazed over like he was watching two strangers play a particularly dull game of cribbage. No indication that he realized he was the pot. Here’s his mother dumping him on a gray-hair with the body of a linebacker—a hundred push-ups every morning since I sprouted my first pubic hair, with plans to keep it up until the day my dick gives out, thank you very much—who happens to be,

surprise, you probably thought he was dead, but!

his long-lost daddy, and the kid’s about as fired up as a pet rock.

I envied him his decade of ignorance. There’s nothing more beautiful than a void, a blank screen you can project all those Technicolored fantasies onto, no one to tell you they’re misplaced or far-fetched. Easy enough to fill that father-shaped hole with the tall tale of an astronaut daddy stranded on the moon or a CIA daddy defusing bombs in some windswept foreign desert. That could be an epic hero’s blood running through your veins, the strength of an Achilles, the bravery of an Odysseus encoded in your DNA. Who wouldn’t be disappointed to come face to face with the real thing, to trade in epic poetry for the genetic equivalent of a joke on a bubble gum wrapper? I knew he couldn’t look at me without seeing himself, at least the funhouse mirror version—

congratulations, this will soon be your life

–just like I couldn’t look at him without wincing at what had once been and what was to come.

His hairline was several inches closer to the brow line than mine but already receding, and it would be a few more decades before his crooked nose and uneven eyes came into their Picasso-like own, but he was already skidding down a slippery slope. I’d had that same thatch of sandy hair, and whatever I’d lost on top was replenishing itself in my nostrils and ears, conservation in action. I’d have to be blind to doubt he was my kid, and he’d have to be nuts not to want to trade me in for a better model. But he didn’t look disappointed. He didn’t look much of anything. I wondered if he was autistic or something. Glory be. Not only did I have a kid, but the kid was weird.

“Parenting’s not complicated,” Hilary said. “Accept that you’ll fuck him up, whatever you do. Just try not to fuck up so bad that it kills him.”

“I’ll put him out on the street as soon as you’re gone,” I warned her.

She grinned, the way only someone who’s seen you roll off her naked body with a groan and a

must’ve had too much to drink

while she said

it happens to the best of ’em

and you both thought

no, it damn well doesn’t

can grin.

“No. You won’t,” she said. And she was right about that, too.

• • • •

The kid was no prize. He knew how to talk, at least, turning into a regular chatterbox once his mother peeled away, informing me in nauseating detail about what he required in terms of food, bedding, shampoo brand, toothpaste flavor, internet access, a list that stretched on in such detail and scope that I had to call in one of the Children to take notes.

“What, no limo?” I said, once he was done laying out his demands. “You don’t want to throw in a request for a weekly manicure or your own personal masseur?”

Mandy Herman, who was scribbling down everything that came out of the kid’s mouth, shot me a sharp look, and I wasn’t sure if it was because she didn’t think sarcasm was appropriate or because every few days I called her into the office and rewarded her with the opportunity to rub some life back into my shoulders, spine, and ass.

“You said you didn’t know what to do with a kid,” the kid said. “I’m telling you.”

Mandy, that traitor, laughed.

He was, it turned out, like one of those preciously precocious movie kids, the kind who melts the smiles of old men, heals the hearts of bickering lovers, and teaches every neighborhood Grinch the true meaning of Christmas. This, despite the big ears and the lopsided face and the fact that he never shut up.

It did nothing for me, but the Children gobbled it up with a spoon. He wasn’t there twelve hours before they took up a collection of spare kid junk: secondhand clothes and filthy toys and a brand new racecar bed courtesy of our very own Scrooge Jeffries. Mandy Herman vied with the Babbage girls for babysitting duties, eventually compromising on a roster that had Mandy on the couch with him Monday through Wednesday afternoons while the three Babbages—buxom and blond in a way that the kid was a few years too young and I was a few decades too old to make use of—covered the rest.

Alison Gentry, who’d been a high school math teacher in her discarded life, had taken charge of the younger Children’s education, setting up a one-room schoolhouse in what used to be the stables, and it was no trouble to scoop the kid into the fold. We had no others exactly his age—a clutch of toddlers, some first and second graders, and of course the Babbage girls—but the kid seemed to prefer the company of adults anyway, if you could call the Children that, and with their naïve, infantile willingness to believe as they were told, maybe that made sense.

Because what child doesn’t love a story? And when you get down to it, that’s all I am: a storyteller. Nothing more, nothing less. Back in the Hilary days, I’d thought I needed more smoke and mirrors, some laying on of hands, but eventually I wised up. You don’t need to cure the lepers to be a faith healer. We’re all of us in my business doing the same work, because what is faith but another story that you tell yourself to feel better? That’s what these idiot skeptics, the do-gooders, the ones so desperate to snatch the wool from my Children’s eyes, would never understand: Lies don’t hurt anyone. Lies are the balm;

truth

is the wound.

Even the Man himself, if you believed in him up there, napping on his cloudy throne, doesn’t have much more than pretty stories to offer these days. Sure, Joseph, Moses, Jesus’s precious lepers,

they

got miracles. But now? God’s out of the direct action industry, and all he’s offering in its place is a bedtime story. The fairy tale of heaven, the promise that whatever shit happens, your story gets a happy ending. The Bible, boiled down: Once upon a time I helped some poor suckers out and someday, maybe, if you’re good, I’ll help you too, but in the meantime, isn’t it a nice story to fall asleep to?

You can’t say I’m not doing God’s work.

All those social workers, estranged relatives, those Pittstown neighbors who turned their nose up at the Church buying up property in their suburban midst, they called us a cult. Maybe so. But the word carried a sinister whiff that didn’t match up with its reality, something that maybe you had to be in a cult—or in charge of one—to know. My Children were gentle, most of them treading through life with the care of the permanently damaged, whether by drugs, abuse, or simply the ordinary existential indignities, loss of job, loss of love, loss of dignity, loss of purpose. That was their universal: Loss. Who else would so desperately need to be found?

That’s what I’d done when I first arrived in Pittstown, what I did when I arrived anywhere: I collected the lost, the ones who’d fallen through the cracks, like a dog-catcher scooping up strays for the pound. It was a service, not just to the feral, but to the tame and well-housed, all those cocky, secure, too good-for-it-all townsfolk satisfied with the comfort of their own homes who preferred not to acknowledge what I was doing for them, tending to their damaged so they wouldn’t have to.

Alison Gentry’s sister left nasty voicemails every few months, and once she’d set the local cops on us, but where was she when Alison’s three kids and husband plowed through a guard-rail and into Lake Michigan? Where was she a year later when her sister washed down the anniversary with a vodka and Percodan cocktail?

Where were Mandy’s parents—with their team of trust-fund-busting lawyers doing everything they could to keep her hands off her money—when she and her crack pipe had driven a Pontiac through a neighbor’s living room window, and then been promptly hauled off to jail, where she stayed, because mom and dad thought teaching her a lesson would be kinder than bailing her out?

Where were Clark Jeffries’ kids when his board of directors dumped him on his ass, or Merrilee Babbage’s husband when—having been traded in for a secretary with a bad dye job and a dick—she was feeding her three kids with food stamps and blowing the landlord when she couldn’t make rent?

I

was the one who wiped their tears and salved their wounds and fed them some bullshit to live for, and if I took a little something with me when I went, it was only fair payment for services rendered.

Despite my best efforts, plenty of the Children still had a hole to fill, and somehow, with his ugly, gap-toothed smile and post-nasal drip, the kid filled it.

That was my smile. Those were my mother’s big ears and my father’s vampire canines—and the way he chewed his nails, but only the ones on his left hand, was like seeing my brother’s ghost. This was the kind of genetic detritus that was, I knew, supposed to kindle a fire in me, as if it mattered that we came from the same stock.

I didn’t know whether my parents were alive or dead, and didn’t much care—had never understood it, this obsession people have with

blood

. This fixation on

children

, as if popping a baby out and watching him grow into your big nose and type 2 diabetes was your best shot at staving off oblivion.

Ask people to worship you? They call you a megalomaniac. Ask them to worship your kid? They call that good parenting.

Still, I played along, let them all believe what they needed to believe. That was, after all, my business. And it wasn’t the hassle I’d expected, raising a kid, especially with the Children so eager to do it for me. It was only once he started up with the questions and all that end-of-the-world shit, that the trouble really started.

• • • •

He’d been at the compound for a week, and though I dumped him on the Children whenever I could during the day, at night he was all mine. He got himself set for bed all on his own—

mom calls me her little man

, he said, when I caught him flossing for the third time in a day, and that was the second and last time he mentioned her—but my responsibilities had been made clear.

“At eight, you tell me it’s time to go to bed,” he told me the first night. “I read for a while, and then at nine you come back and turn off the lights.”

So that’s what I did, standing in the dark for a while after, watching this kid—my kid—lie on his back with his legs straight and his arms crossed across his chest like a fucking corpse.

I made that

, I thought, and waited to feel something.

“You got everything you need?” I said. This was before the racecar bed and the hand-me-down pajamas. “Comfortable?”

He didn’t look it.

“Sometimes I like to practice being dead,” he said, staring up at the ceiling.

“You’re a weird kid, you know that?”

“She’s not coming back, is she?”

That was the first time he mentioned her. And because he wasn’t crying or behaving anything like you’d expect from a kid in his situation, I gave it to him straight. “Doesn’t seem likely.”

“Because I’m weird?”

“Because she’s a loser.”

“Oh.”

“Always was. Always will be. You’re probably better off.”

“Doesn’t seem likely,” he said. Then, apparently finished playing dead, he curled up on his side. I watched him until he fell asleep.

That’s how it went until the night, one week after she’d dumped him, when he broke routine. I’d just turned out the lights when he said, “I get five questions.”

“What?”

“Before I go to sleep, I get to ask five questions.”

“Says who?”

There was no answer, and so I knew who.

“Why now?” I said. “All of a sudden?”

“I was waiting until I had the right questions.”

That didn’t sound promising. “I don’t think so,” I said.

“I’m willing to negotiate.”

“Negotiate what?”

“Questions,” he said. “How about four?”

“How about zero.”

“Three questions.”

“No questions.”

“You’re really bad at negotiating,” he said.

“That’s a matter of opinion.”

That was when, for the first time since he’d set foot on the compound, he burst into tears. Burst like a clogged pipe, ten years of misery spraying out of him in a gusher, and even in the dark I could read his fury, that his pathetic little body had betrayed him. I remembered that, trying to survive the battle zone, dodging artillery fire between the kid you were and the man you were supposed to be. The world screamed at you to grow up, your zits and your twitchy dick agreed it was about time, but you were still afraid of the dark, you still slept with that old teddy bear, you still wanted your mommy.

Maybe you always wanted your mommy.

“Okay. Three questions.”

And that right there was my mistake.

• • • •

“Do you really get messages from God?”

“I do.”

“How?”

“It varies. Sometimes I read His intent in the signs. Sometimes He’s got something more direct he wants to say, and He talks to me in my dreams.”

“Why you?”

I shrugged. “Why not me? I didn’t ask for the responsibility, I’ll tell you that much. It’s no picnic, devoting your life to the word of the Lord. You’d be surprised how many people don’t want to hear it.”

“How do you know it’s really God? That you’re not just hearing voices or something?”

“That’s four questions. Good night.”

• • • •

“Does God hate us?”

“God loves us. We’re all his children.”

“And you have to love your children.”

“That’s the rule.”

“That wasn’t a question.”

“Got it. Thanks for clarifying.”

“If he loves us, why would he kill us?”

“Everyone dies, kid. It’s not punishment; it’s human nature.”

“No, I mean, why would he kill

all

of us. Jessie Babbage says the world is going to end. In eight months and twenty days.”

“That another question?”

“The question is: Is it true, the world is ending?”

I won’t pretend I felt good about it, but there was no other way. The kid had shown no sign he’d inherited his mother’s proclivity for bullshit, and I couldn’t show my hand without risking he’d spread the good news like a virus. “It really is.”

There was a long silence, long enough to make me nervous.

“What do you think of that?” I said.

“I think it explains a lot.”

• • • •

“How’s it going to end?”

“You mean, specifically?”

“Yeah. Nuclear war? Asteroid strike? Global warming? I read online about a giant volcano that might explode and kill us all. Also there could be a plague. Or some kind of alien invasion, but that’s not statistically likely. Did your dreams say which it is?”

“God’s a little hazy on the details,” I said. “But the Bible’s got a lot to say on the subject, if you’re interested.” I wasn’t about to give him the whole Beast rising from a lake of fire sermon—let the Children take care of that.

“What will we do? When it happens?”

“We’ll go to heaven with the rest of the righteous people,” I said. “Nothing for you to worry about.”

“You don’t even know me. How do you know I’m righteous?”

“Fair point.”

After that, the kid started having nightmares. And maybe I was partly responsible, but what kid doesn’t have nightmares? Anyway, these particular nightmares? Gold. Because he told the Children about them, and the Children took them to heart, figuring any kid of mine having visions of the apocalypse must be getting his info straight from the horse’s mouth. Purse strings started to loosen. No one wanted to be counted among the sinners when the big day came. Maybe I helped it along a bit, encouraging all that talk of divine visitation, but it’s not like I was forcing the dreams on him.

I just put them to good use.

• • • •

“If we know when the world is going to end, shouldn’t we be

doing

something about it? Like, warning people? Or doing something to save ourselves?”

“That sounds like three questions.”

“It’s one,” he said. “Multi-part.”

“Uh huh.”

“So?”

“So we don’t have to worry about it, because God’s going to save us, and whoever else he wants. That’s the whole point.”

“But don’t they say God helps those who help themselves?”

“Where’d you’d you hear that?” It wasn’t one of my favorites. Operations like mine didn’t tend to thrive on a philosophy of self-reliance and personal accountability.

“The internet.”

It killed me, the way people said that now, like they used to say “the Bible.” Or “TV.” As if it were Truth.

“I don’t think the end of the world is one of those help-yourself situations,” I said.

“But what if you’re wrong?”

• • • •

He wouldn’t let it drop. He wouldn’t keep it to himself, either, and before I knew it, the Children were buzzing with the prospect of preservation. The kid was a natural, only ten years old but already better than I was at talking people around to his way of looking at things. I’d taught them to be open to persuasion, and they were model students, repeating the kid’s questions and arguments and internet-supplied statistics about asteroid impacts like a bunch of ventriloquist dummies. I did my best, pointed out that righteousness was all about faith and faith was all about accepting your fate and waiting for God to intercede, and that’s when the kid—who had apparently taken my suggestion on the Bible-reading front—brought in Noah. Before I know it, we’re building a damn ark.