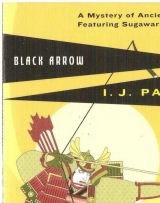

Текст книги "Black Arrow "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

* * * *

Black Arrow

[Sugawara Akitada 04]

By I. J. Parker

Scanned & Proofed By MadMaxAU

* * * *

* * * *

CHARACTERS

In Japan, Family names precede given names for persons of rank.

Main Characters

Sugawara Akitada Deputy governor of Echigo province

Tora, Hitomaro, Genba His lieutenants

Seimei His secretary

Tamako His wife

Hamaya Head clerk of the provincial administration

Yasakichi, Oyoshi Two coroners

Chobei, Kaoru Two sergeants of constables

Characters Involved in the Cases

Uesugi Maro The old lord of Takata castle, provincial chieftain,

and high constable of Echigo

Uesugi Makio His son and heir

Kaibara Steward to the Uesugi family

Hideo Servant to the old lord

Toneo Hideo’s grandson

Hokko The abbot of the Buddhist temple

Takesuke Commander of the provincial guard

Mrs. Sato An innkeeper’s widow

Kiyo Her maid

Takagi, Okano, Umehara Three travelers arrested for murder

Sunada A wealthy merchant

Boshu Sunada’s agent

Hisamatsu A judge

Mrs. Omeya A widow

Goto A fishmonger

Ogai His brother, a deserter

Koichi A porter

Also: Tradesmen, outcasts, servants, and constables

* * * *

BLACK

ARROW

* * * *

PROLOGUE

THE FATAL ARROW

Echigo Province, Japan:

Leaf-Turning Month (September), A.D. 981

T

he evening sun slanted through the branches of tall cedars and splashed across a bloodred maple on the other side of the clearing. From the valley below came sounds of horses and shouts of men.

A young woman emerged from the trees, leading a child—a boy, no more than three years old, in bright blue silk and with his hair childishly parted and tied into loops over his ears. The young woman was slender and beautiful, and dressed in a costly white silk gown embroidered about the hem and full sleeves with nodding golden grasses and purple chrysanthemums. Her long hair, which almost reached the hem of her dress, was fastened with a broad white silk ribbon below her shoulders.

In the middle of the clearing the child pulled free to chase a butterfly. The young woman called out anxiously, then laughed and ran after him.

From the thicket, Death watched the two with hot eyes, clasping the large bow with his left hand, while the right slowly reached over his shoulder to pull the long, black-feathered arrow from the quiver slung across his back.

The boy lost the butterfly and turned toward the woman, who sank to her knees and spread her arms wide to receive the child.

Death bared his teeth. He was close, his bow powerful, the arrow special. With luck it might take only the one shot. He placed it into its groove, pulled back firmly, and aimed.

With a shout of laughter the boy hurled himself into the waiting arms, and Death released the long steel-tipped missile. He watched as it found its mark just below the silken ribbon in the woman’s black hair, heard the muffled blow clearly in the sudden silence, and watched as she fell forward, slowly, burying the small figure of the child beneath her. Heavy silken hair slipped aside, and a large red stain appeared on her white silk gown, spreading gradually from the black-feathered arrow like a crimson peony opening its petals in the snow.

Even the birds had fallen silent.

Death remained frozen for a few moments, watching, listening. But there was neither cry nor movement under the white silk, and he slowly lowered the bow.

The silence was broken by a small bird’s voice, then by the humming of insects and distant shouts of the hunting party in the valley. Death quickly left the clearing.

* * * *

ONE

THE OUTPOST

Echigo Province, Japan

Gods-Absent Month (November), A.D. 1015

T

wo men armed with hunting bows rode single file down the steeply sloping track toward the dark huddle of buildings on the plain below. They hunched into heavy clothing against a sharp wind that swept across the black-and-gray landscape of rock, evergreens, and sere grasses. Below them the black roofs of the town were a blot in a wintry plain, and beyond the plain a pewter ocean stretched toward a distant line where it melted into the murky grayness of low clouds. A highway ran along the shore. Behind the horsemen rose mountains, their tops hidden in gray vapor.

The prospect was dismal.

Most of the town straggled along the black line of the highway, which looked not unlike a dead snake with a large rat bulging its middle. The rat bulge contained the tribunal and a small temple, surrounded by low, steep-roofed houses—the center of Naoetsu, capital of Echigo province.

This was the rough north country, won only recently from its barbaric inhabitants and not yet fully civilized. In the short summers, the plain between the mountains and the ocean was green with fields of rice, ramie, and beans, and the ocean dotted with fishing boats. Echigo was a fertile province, but now it prepared for the long winter, when a thick blanket of snow covered the land, and men and beasts lived like bears inside their homes until the snow melted in the spring.

The rider in front, a muscular man with a neatly trimmed graying beard and the sadness in his eyes that attracts women, looked out at the choppy sea and up at the roiling sky. The wind was bitterly cold. He called over his shoulder, “Looks like snow.”

“Smells like it, too.” His younger companion in the bearskin coat gave a shiver and pulled his handsome face back into his collar like a turtle. A string of birds dangled from either side of his shaggy pony’s neck. “Nothing like we expected, is it, Hito?” His voice was muffled by the fur.

“Few things are. The master was sent here to set things right.”

“It’s another trap, I bet,” grumbled the young man into his bearskin. His name was Tora, or “Tiger.” He had chosen it years ago when his birth name had become a problem. Fifteen years Hitomaro’s junior and from peasant stock, he had served their master longer and was closer to him. Hitomaro—Hito for short—had only joined them a few months ago in the capital, along with his friend Genba.

“How so?” asked Hitomaro.

“Reminds me of Kazusa. He was meant to fail there, too, but he was hot to succeed, sure it would make his career. They sent him on a wild goose chase, hoping he’d screw up. He gave ‘em a black eye instead.”

“This time his friends got him the assignment.”

“Don’t you believe it. This is much worse. They’re letting him fill in for some prince who’s taking his ease in the capital and raking in most of the income. Only this time they made sure they tied both the master’s hands behind his back so he couldn’t defend himself. And then they hobbled his feet so he couldn’t get away. What gets me is he’s all fired up again anyway.”

“Then he’ll succeed just like last time.”

“With just the three of us? When the whole province is about to rise up in arms against him?”

“You don’t know that. And we are four. You forgot Seimei.”

“Amida, brother! That old man’s never held a sword or a bow. Even her ladyship can at least ride a horse.”

“Seimei is smart. Stop complaining, Tora, and let’s move on. We’ll have to cook the birds tonight.”

“Heaven help us,” muttered Tora. “I wish we could make Genba do it. He likes food.”

Hitomaro, who had reached level ground, urged his horse into a trot. He called back, “Genba eats. He doesn’t cook.”

Tora followed. If the truth were known, he was by nature an optimist but he hid his confidence in hopes of impressing the older and more worldly wise Hitomaro with his experience.

On the outskirts of the city they encountered a disturbance at a mangy hostel called the Inn of the Golden Carp. The place was, despite its fancy name, a mere collection of low hovels, the sort that serves bad food in skimpy portions but generous helpings of vermin.

“Wonder what’s going on there?” Tora’s face emerged from his bearskin as if he smelled excitement.

Hitomaro spurred his horse, scattering the gaggle of people staring through the gate, and rode into the inn yard. Tora followed, and so did the spectators. A constable in a patched brown jacket and dirty trousers met them. “Nobody’s allowed,” he cried, waving his arms. “Disperse. By order of Judge Hisamatsu.”

Hitomaro and Tora ignored him and dismounted. They tied their ponies to a post, but the constable drew hisjitte and barred their way, swinging the two-pronged metal weapon at them.

“Hey! I said ...”

Hitomaro growled, “Put that toothpick down and stand aside. By order of the governor.” Sweeping the man out of his way, he stalked past him into the main hovel.

Tora slapped the constable’s shoulder with a grin. “Didn’t recognize us? Keep an eye on our birds, will you?” He pointed to the string of freshly killed quail and doves.

Inside, a dank stone-flagged passage led past the kitchen toward a large common room. An odor of dirt and garbage hung about the place. No point in removing shoes; the floors were either stone or dirt and could have used a sweeping out.

In the kitchen, a slovenly maid stood beside the hearth, sniveling into a corner of her skirt. Tora deplored the dirt but scanned with interest her shapely ankle and an immodest expanse of leg and thigh.

Hitomaro was already in the common room, another dirt-floored space with a central fire pit. The fire was out and the room empty except for Hitomaro and a stocky character in half armor.

They knew Chobei and he knew them. Chobei was the sergeant in charge of the tribunal’s constables, and they were the newly appointed lieutenants in the governor’s staff. Chobei was a local and theoretically under their command but did not see it that way Relations were becoming strained, because Hitomaro and Tora had no plans to relinquish their authority. Never mind that they represented the entire governor’s guard, they still outranked Chobei.

“This is a local matter,” Chobei was saying, pushing out a pugnacious chin. “Nothing to do with you. I’ve sent for the judge.”

Hitomaro snapped, “Everything in this province concerns us. What happened here?”

“Just a simple robbery. Done by outsiders.”

Tora raised his brows. “Outsiders? What do you mean?”

Chobei sneered, “I mean strangers. Not by our people.”

“Ah.” Hitomaro pretended interest. “And how do you know that?”

Chobei cast up his eyes. “It’s an inn, isn’t it? People who don’t live here stay at inns. Strangers. Outsiders. Like you.”

Tora growled in the back of his throat. Hitomaro gave him a warning look. “What about the owner?” he asked. “The maids? The staff? Any of them could be involved. Who was robbed and what was taken?”

The sergeant smirked unpleasantly. “If you must know, it’s the owner who was robbed and all his gold was taken. Right out of his locked chest.”

“I want to speak to him.”

Chobei snorted. “Can’t. They cut his throat.”

“Look here, you useless piece of garbage,” Tora exploded. He pushed Hitomaro aside to get his hands on the sergeant and teach him a lesson in manners.

Chobei backed off, yelling, “Be careful. I’m in charge here. The judge won’t like you interfering in the execution of my duty. This is a serious crime.”

Hitomaro held Tora back. “Carry on, Sergeant,” he said. “We’ll just take a look to make sure we report the matter correctly to his Excellency.” Without waiting for an answer, he headed to the back of the inn. Tora scowled at Chobei and followed.

The dingy passage led to dingy rooms, all of them apparently empty. The last one seemed to be the owner’s, and dirtier than the rest. Its floor was stamped earth, but in one corner was a wooden sleeping platform large enough for three people. Filthy blankets lay tumbled about the corpse of a fat elderly man. The man’s torso and most of the blankets were soaked in blood. Beside him an empty wooden box rested on its side. It was the sort of box small shopkeepers keep their money in, with iron clasps and a lock. The lock had been forced.

Tora looked at the corpse. The dead man’s mouth gaped above a gruesome wound in his throat. “Ugly old bastard,” he muttered. “Looks like a toad snapping for flies.”

“If he was asleep, it wouldn’t take much strength to cut his throat with a sharp knife,” remarked Hitomaro, looking around. “I don’t see a knife, do you?”

“No. Wonder how much they got. Couldn’t be a fortune in a place like this.”

Chobei put in his head. “Satisfied?” he sneered. “Here’s the judge.”

Judge Hisamatsu bustled in as fast as short legs could carry a large paunch and thick layers of clothing. He had a round, clean-shaven face with pinched lips. The cold wind had given it some color, but he looked the sort of man who rarely spent time in the outdoors. At the moment he was irritated. “What’s this then?” he demanded. “Can’t you do anything yourself, Chobei?”

Chobei bowed. “A murder, your Honor. Nasty. I thought...” he began apologetically.

The judge stared at Tora and Hitomaro. “What are these people doing here? Get rid of them. Is that the victim?” He waddled to the platform, peered, and immediately turned away. “You might have warned me,” he said, gulping air.

The unfairly chastised Chobei bowed humbly. “Very sorry, your Honor. I tried, but being kept by idle questions, I was unable to greet you. It won’t happen again.”

“See that it doesn’t. Where’s Yasakichi?”

“The coroner has been notified, your Honor.”

The judge twitched impatiently. “Well, he should be here then. Must I do everything? What happened?”

“Murder and robbery, sir. The victim’s name is Sato. The owner of the inn. His money box has been broken open and his gold is gone.”

The judge glanced at the box. “Ah. You have arrested the killer?”

“Killers, your Honor. No, sir. Not yet. But they left only a few hours ago. On foot. I’ve sent a constable to the garrison with descriptions. The soldiers will bring them back shortly.”

“Good. Anything else?”

“No, your Honor.”

Hitomaro cleared his throat and stepped forward. “Your pardon, your Honor,” he said, “but could we find out about those killers?”

The judge peered at him in the poor light. “Why? Who are you?”

Hitomaro saluted. “Lieutenant Hitomaro, sir. And this is Lieutenant Tora. In his Excellency’s service.”

Tora straightened up a fraction.

“What? What Excellency? I don’t know you.”

Tora gave another low growl, which was somehow appropriate for his bearskin and made the judge skip a step away from him.

“The governor, your Honor,” Hitomaro said, keeping a straight face while kicking Tora in the ankle.

“The governor? Oh, you mean you’re with the fellow from the capital? Sugawara?”

“Look here,” Tora burst out, “you’d better keep a civil tongue—”

Hitomaro got a hard grip on Tora’s arm. “His Honor probably hasn’t been fully informed, Tora.” Turning back to the judge, he said smoothly, “His Excellency, Lord Sugawara, has been duly appointed to take over the administration of this province. The imperial decree was read in front of the tribunal a week ago and a copy is posted on the notice board. I’m sure your Honor will wish to pay him a welcoming visit.”

Judge Hisamatsu opened his mouth, thought better of it, and waved it aside. “Yes, well, we’ve been very busy. But I’m sure you won’t be needed in this case.”

“About the suspects,” Hitomaro persisted. “Could we be told about them?”

Hisamatsu hesitated. “Well, it’s not really your business, but I see no harm in it. Chobei?”

Chobei bowed. “There were three of them. Riffraff. The maid described them. They came separately, but left together before dawn today. When she got up, she found them gone and her master dead. Two of the men come from far away. A peddler by the name of Umehara and an unemployed actor called Okano. The other man claims to be a local peasant by the name of Takagi.”

“There you are,” said the judge to Hitomaro. “Now please go. Here is Dr. Yasakichi.”

“Just a minute—” Tora started, but Hitomaro took his arm and pulled him out of the room. In the dim passage they moved aside for the coroner, dingy-robed and carrying a satchel.

Hitomaro released his companion when they were back in the drafty courtyard. “Look,” he said, “you’ve got to control your temper better. We don’t know what’s what yet and you can’t be making enemies before we even get to know these people. Remember what the master said.”

Tora felt rebellious but nodded. “I guess you’re right, brother. Did you smell that coroner? Not that I blame a man for having something to warm his belly in this weather.” He gestured across the highway. “Since we didn’t get much information here, how about a cup of hot wine in that shack over there?”

The “shack” was opposite the post station next door. A train of pack horses was leaving, the grooms shouting and whipping up the animals. Steam rose from their shaggy coats in the cold air. Near the wineshop, a few hawkers had set up their stands. Bundled up, they were selling straw boots and rain coats, rice dumplings, and lanterns to travelers departing for the warmer south before the snows came. The onlookers at the gate were gone, no doubt beaten back by the constable.

Tora and Hitomaro crossed the street after the pack train. A tattered bamboo blind with faded characters covered the door of the wineshop. They lifted it and ducked in.

A thick miasma of smoke, oil fumes, and sour wine met them. The light was dim because both tiny windows were covered with rags and blinds to keep out the frigid air. What little light there was came from oil lamps attached to the walls and from a glowing charcoal fire in the middle of the small room. A handful of customers sat around the fire, and an ancient woman, round as a dumpling, was pouring wine and carrying on a conversation. An even older man, his thin frame bent almost double, bustled forward. Hitomaro and Tora decided to stay away from the haze around the fire and sat on an empty bench near the door. Leaning their bows against the wall, they ordered a flask of hot wine.

“What did you make of that?” Tora asked, jerking his head toward the Golden Carp.

Hitomaro looked thoughtful. “Lack of cooperation. Not surprising, really. The judge wasn’t too sure of himself, though, or we wouldn’t have had the time of day from them.”

“I meant the murder.”

Hitomaro chewed his lip. “Could be it happened that way.”

“I don’t think so.”

“Oh?”

“A peddler, a peasant, and an actor agreeing to kill an innkeeper on the road? They wouldn’t agree to do anything together.”

“How do we know that’s what they are?”

“The maid said so.”

“Maybe the maid lied.”

Tora considered the maid until their wine came. Her shapely legs featured in his thoughts.

The old man set down the flask and two cups along with a plate of pickles. “Are the gentlemen new in town?” he asked, peering at them from watery eyes,

Tora tasted the wine. It was thick with sediment and sour. He put down his cup. “You guessed right, uncle. Looking for a place to stay Someone told us the inn over there is cheap, but there’s been a murder. We don’t like places where they kill the guests.” He held up the flask. “How about joining us in a cup?”

“Thank you, thank you!” The old man cast a furtive glance toward the old woman and produced a chipped cup from his sleeve. This Tora filled, and the old man drained it, smacking his lips and tucking the cup away again in the twinkling of an eye. “As for the Carp,” he said with a toothless grin. “It’s old Sato, the innkeeper, who was killed and the guests did it. Serves him right. The old skinflint puts up anything that crawls in off the road and has a few coppers. His poor wife’s been trying to spruce up the place and bring in a better clientele.” He cast a dubious glance at their rough clothes, his eyes lingering on Tora’s bearskin.

Tora sampled the pickles and found them excellent, crisp and nicely spiced. He slipped off the bear skin and revealed a neat blue cloth jacket underneath.

The old man looked relieved. “It’s been hard for that young woman,” he said, “running a place with such a husband. Like an ant dragging an anchor.”

Tora grinned. “Well, she’s rid of the anchor now. Young, you say?”

The old man chortled. “Oh, my, yes. And a beauty! Old Sato didn’t deserve the pretty thing, and that’s the truth. But she knows it, so don’t get your hopes up.” He sighed. “Some men have all the luck.” He cast another furtive look over his shoulder, started, and put a gnarled finger to his lips.

The old woman waddled up. She gave them a nod and told the old man, “I need some firewood if you want me to cook the rice and keep the wine warm. Somebody’s got to do the work if we’re to eat.”

“Get it yourself. My wife,” he said to Tora, rolling his eyes. “Can’t stand to see a man rest. Ask her about the Carp. She knows everything.”

Tora turned on the charm. “Lucky you. Your lady’s not only fetching but well-informed. I bet she makes these delicious pickles herself.”

The woman’s round face widened into a broad smile nearly as toothless as her husband’s. She sat down beside Tora. “A family recipe. Been making them all my life. So, where are you two from?”

“The capital,” Hitomaro said, chewing a pickle. “We stopped across the street first. You know anything about the murder?”

She nodded. “It should suit the whore just fine,” she said darkly.

Her husband bristled. “You’ve no right to call her that, woman.”

Tora laughed. “If she’s as beautiful as your husband says, I might court her myself—now that she’s single again.”

“Then you’d better watch out. That one’s a fox,” snapped the old woman.

“Horns grow on the head of a jealous woman,” muttered her husband.

She punched his arm. “What doyou know about such women?”

“Pay no attention to her, young man,” the old man said, rubbing his arm. “Mrs. Sato was a good little wife. Dutiful daughter, too. Not many young girls let themselves get sold to a cranky old geezer like Sato.”

Hitomaro put in, “I don’t think she was home just now.”

“She went to visit her sick mother yesterday,” the old man said. “Maybe she’s gone back.” His wife gave a snort, and he glared at her. “A dutiful wife and daughter, I say, and a fine little manager, too. She’ll do wonders for the place now that old Sato’s dead.”

“Hah!” said his wife and left.

Her husband stayed. “Sato was a terrible miser. He let the inn run down. Charged bums a few coppers for a place by the hearth and a bowl of beans or millet with wilted greens. His wife’s been wanting a nicer place.”

The fat little wife came rolling back with another plate of pickles. She said, “Guess what? One of the men’s from Takata. He says the old lord’s dying.”

Her husband pursed his mouth. “Lord Maro? He’s been dying for years. But I’d better lay in more wine anyway. If it’s true, we’ll be busy around here for the funeral.” His face broke into a happy grin for a moment, then he said piously, “Lord Uesugi’s the high constable. May he be reborn in paradise.”

“If he’s the high constable,” Tora said, “he’s had a good life already. Save paradise for us poor people.”

“You wouldn’t want to trade places with him,” said the old man. “There’s a curse on that clan.”

“A curse?”

“Ah, terrible things happen to them. Take Lord Maro’s older brother. He used to be a champion with the bow and could hit the eye of a rabbit at two hundred paces, but one day he killed his father’s wife and her little son. Killed his own brother!”

“What happened to him?” Hitomaro asked.

“The angry ghosts ate him.”

Tora’s eyes widened. “Really?”

The old woman rolled her eyes and cried, “It’s the truth. The ghosts of that poor young lady and her babe. He was never seen again.”

Her husband scowled. “I’m telling the story.” He turned back to Tora and Hitomaro. “Lord Maro’s father was pretty old when he married again and had another son. I should be so lucky!” He gave his wife a meaningful look. This sent her into hoots of derisive laughter and she waddled back to her customers.

“So? Go on,” Tora said.

“Well, they found the lady and her boy in the forest. Killed by the same arrow!” He leaned forward. “The older son’s arrow. It went through both of them. Like two birds on a spit. Lord Maro’s father had doted on them and it killed him.” He paused and eyed the wine flask. “You’re not drinking. Can I get you some more wine?”

They shook their heads. Tora said, “How about another cup for you?”

In a flash the cup reappeared from the old man’s sleeve. Tora filled it, the old man gulped it down, tucked the cup away, and continued, “Well, Lord Maro succeeded his father, but he had no luck either. Only one of his children lived. That’s Makio. But Makio’s wife died young. They say she jumped off the upper gallery a few weeks after the wedding. He never married again. Then Lord Maro went out hunting and lost his mind. Came back raving mad. Locked himself away and never came out of his room again. They say there’s crying and wailing day and night in that room. It’ll be a blessing if he finally dies.”

Tora gave a shudder. “Angry ghosts will drive a man mad.”

The old man nodded. “Mind you, there’ll be more trouble soon. It’s the new governor. Makio will get rid of him, just like his father did the last one.”

“What?” Tora and Hitomaro asked together.

“Hah! You don’t believe me? Name of Oda. Came from the capital just like this one and wanted to run things. Broke his neck falling off a horse. They called it an accident.” He snorted.

Hitomaro said, “It wasn’t an accident?”

“His horse came home with an arrow in its ass.”

Tora and Hitomaro exchanged glances, then Hitomaro got up and tossed some coins down. “That’s foolish talk,” he said harshly. “If someone raises a hand against a governor, the emperor sends an army to teach them proper respect.”

“Well,” the old man swept up the coins, “it’ll make trouble all right. That’s always the way in the end.’“

Outside, Tora asked, “You think there was any truth to that?”

“To what? The murdered governor? Or this Makio’s plans for us?”

“Both.”

“No idea. He had no reason to lie and he seemed rational enough—except for that ghost business. They say rumors are more honest than official welcomes. We’d better report it to the master.”

But when they got back to the inn yard, Tora burst into a string of curses. His catch of birds had disappeared—all but one skinny dove which had been nailed to a pole with a knife. Stuck to the knife was a piece of paper with the words, “This will be you next time.”

* * * *