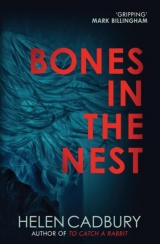

Текст книги "Bones in the Nest"

Автор книги: Helen Cadbury

Жанр:

Криминальные детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

‘You know him?’

‘Of course, I thought I told you,’ Maureen said. ‘He’s batty Bernadette’s lad, different name because he was from the first husband, John Starkey. John used to work at Markham Main with your dad. Died in a scaffolding accident not long after the strike. Fell off drunk probably. Anyway, then she married Bob Armley.’

Sean tried to process what he was hearing.

‘That poor woman,’ she said. ‘As if she hadn’t had it hard enough after losing the younger one, that Terry went and got himself banged up for armed robbery.’

‘Come again?’

‘I thought you knew. The one that got pushed off the flats, that was her younger son. Terry tried to use it in court, in whatsit …’

‘Mitigation?’

‘That’s right. But his was a nasty crime. Armed robbery’s armed robbery, at the end of the day.’

He thought about the pictures in Bernadette Armley’s flat – two young boys with red hair and freckles.

Maureen topped up his tea and sat back in her chair, lighting up a cigarette.

‘First one of the day,’ she sucked on it with her eyes closed.

‘Nan, you shouldn’t. It’s not ladylike,’ he joked.

‘My days of worrying about being ladylike are long gone. Anyway, some fellers still think it’s sexy,’ she laughed a deep smoker’s laugh.

He could sense a dangerous change of subject and sure enough, she was asking him about girls and whether there was anyone special in the picture. He decided to tell her he’d seen Lizzie Morrison, but regretted it as soon as the words were spoken.

‘What’s she doing back in Doncaster?’ Maureen’s eyes lit up. ‘Is she still seeing that bloke from Donny Rovers?’

‘I don’t know Nan, I’ve not really thought about her.’

‘Well you be careful with that one.’

It struck him as ironic that the people who cared about him were constantly warning him to be careful of the people he admired. He wondered if he was gullible, or maybe he trusted the wrong people. But were Lizzie Morrison and Sam Nasir Khan the wrong people? Or were they just people who were out of his league socially, professionally and in every way he could imagine?

‘It’s not right,’ Nan said, ‘the shop being attacked. They’ve gone too far with that Clean Up Chasebridge thing, let it get out of control. I told your friend Rick, I said to him, they’re just jumping on the bandwagon most of them.’

‘He rang you, then?’

‘Yes, I told him you left the meeting early, reckoned you didn’t want to be associated with that lot.’

‘Thanks.’

‘Don’t mention it.’

Maureen refilled his cup, the tea darker than ever.

At that moment his phone pinged with an incoming text and interrupted their conversation. He wouldn’t have recognised the number, but Lizzie Morrison had thoughtfully signed her text. She wanted to know if he was all right. That’s all she said.

‘Who’s that then?’ Maureen said.

‘Lizzie.’

‘Ah,’ Maureen tapped the side of her nose.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘You summoned her. You sent out a temporal vibe and she caught it.’

‘What are you on about?’ Sean said.

‘There was a talk at the library. Some woman who’d written a book about telepathy. It was very interesting. There’s a lot of things we put down to coincidence, which are no such thing.’

‘OK,’ he nodded. ‘Maybe I’m getting temporal vibes from Terry Starkey then. He keeps turning up all over the place. Call it coincidence or whatever you like, but I can’t shake him off. Have you still got the weekly paper? The one with the girl who killed Starkey’s brother?’

‘Outside in the recycling bin. You’re just in time. It’s collection day tomorrow. Now I need to go up and get ready, or I’ll be late.’

He found the paper near the bottom of the box and glanced at the headline. There was the photo of a girl in school uniform, ears sticking out through her straight, dark hair. If only we knew how those terrible school portraits could come back to haunt us, he thought, we’d refuse to have them done.

Back at the kitchen table he read the article carefully, looking for any mention of Terry Starkey or Bernadette Armley, but there was no reference to the family, beyond saying that James Armley was a ‘loving son and brother’. Sean underlined the girl’s name and the year it happened, ten years ago. He circled the words ‘cold-blooded’ and ‘innocent schoolboy’. James was sixteen at the time, which was stretching the definition of schoolboy a little. The same age Saleem was now. Sean went back to the beginning and read more carefully: The victim had been lured to the top of the Eagle Mount flats by jealous Marilyn Nelson, a local girl with whom he’d had a secret love tryst. He saw the word ‘manslaughter’, tucked in the final sentence. So, not a murder then; he wondered why not.

‘I’m surprised Terry Starkey didn’t try to make something of it at the CUC meeting,’ he said, thinking out loud. ‘Wouldn’t hurt his profile to have the sympathy vote.’

His phoned pinged and he remembered he hadn’t replied to Lizzie’s text. He typed his response carefully. Three words. Yes fine thanks. Then he saved her number in his address book. He realised she must have kept his, two years on from their last job together.

Maureen came downstairs in a tracksuit top and leggings.

‘I’m off to Bums and Tums. I don’t like to miss it and I’m going to be late at this rate. See you later!’

She closed the back door and he sat for a while in the silent kitchen, trying to decide what to do next. Nothing. That’s all he could think of. Nowhere to go and nothing to do. He stared at the kettle and wondered about making another pot of tea, but he didn’t move. He looked at his watch and saw it was creeping towards nine o’clock. He didn’t think Jack would be awake yet, but the supermarket on the ring road would be open.

Sean stood up and rinsed out the teapot, leaving it neatly on the drainer. He wished he could stay here, where everything worked and you didn’t feel as if you would stick to every surface you touched, but he knew he had to go back to his dad’s; it had something to do with finishing what he’d started.

He went through to the sitting room and looked around. It was spotless, as usual, with a scent of lemongrass coming from the aroma sticks Maureen had put in a glass vase on the mantelpiece. She’d done away with the plug-in room fresheners when she decided they gave her asthma. He’d tried to suggest that giving up smoking might help with that, but she wouldn’t be told. Maybe this new exercise regime would put her off, although knowing Maureen, she’d probably find time for a fag break at Bums and Tums. He sat heavily on the settee and his head fell back into the soft corduroy cushions. Tiredness crept through every limb, weighing him down. He closed his eyes and let himself drift.

He woke up with a crick in his neck and realised it was nearly midday. In the kitchen, he ran the cold tap and poured a glass of water. He downed the glass in one, rinsed it out and put it on the drainer. The newspaper was still on the table with his annotations in blue biro. He rolled it up, tucked it under his arm and pulled the back door shut behind him. As he turned down the side of Maureen’s house and onto Clement Grove, his phone rang.

‘Hiya! How are you doing?’

‘Hi, Lizzie. I’m…’

‘What?’

‘Nothing. I’m doing nothing, there’s nothing to do. The high point of my day will be scrubbing the rest of the mould off the bathroom tiles in my dad’s flat.’

‘So you are on the Chasebridge estate?’

‘Near enough, just leaving home.’

‘Really? Brill. Any chance you could get us that coffee you were offering? I’m at the paper shop.’

‘Again?’

‘Got turned away yesterday. It wasn’t safe inside the shop. Something to do with the electrics. Now I’ve got to wait until the fire investigators give it the all clear, and they’re late.’

He was glad she hadn’t been there earlier and seen him going upstairs with Ghazala.

‘I’ll see what I can do,’ he said. Lizzie’s stint down south had obviously raised her expectations. This wasn’t coffee bar country, but he had an idea. ‘I’ll be there in a minute.’

She was sitting in her car outside the parade of shops, window down and one bare elbow resting on the door frame. He thought about creeping up to surprise her, but she was obviously checking her wing mirrors because she waved out of the window as he approached. He leant in and she smiled up at him. The radio was playing Mumford & Sons. It wasn’t his kind of music but it suited her.

‘You after a coffee?’

She nodded.

‘Fresh from my nan’s Thermos!’ He produced the red tartan flask with a flourish.

She laughed. ‘Wow, vintage!’

‘I brought a spare cup, if you don’t mind me joining you.’ He wondered where it came from, his newfound confidence around Lizzie Morrison, but as long as it was just about drinking coffee together, he felt he was on safe ground.

‘Let’s sit in the sun and make the most of it,’ she said. ‘I feel like I’m missing the whole summer. I’m either in the office or sweating it out in a plastic suit.’

She got out of the car and clicked the locks on. Sean sat down on the low wall in front of the library and poured the milky instant coffee into two cups. They were both quiet for a while until Lizzie broke the silence.

‘Sean?’

‘Yes.’

‘When I was in London, I missed all this.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yeah. I actually missed Donny, and I missed crappy places like the Chasebridge estate. Funny, isn’t it?’

Sean took a slow mouthful of coffee. Lizzie didn’t notice his lack of response; she was looking at something behind him.

‘What did Mohammad Asaf study at the college?’

‘Media or something,’ Sean said and turned to see what had caught her attention.

In the window of the library, a series of black and white photographs hung from thin steel wires. One was of a tower block taken from below, which made it appear to be toppling forwards away from a cloud-filled sky. In another, a beautiful young Asian woman was on a swing in the playground, her head thrown back and her hair trailing out behind her. Brick walls, concrete, more sky; they weren’t pretty, but there was something moody and artistic about them. A small white sign with black lettering said: Mohammad Asaf, first prize, Chasebridge Community Photographic Competition. Dr Angus Balement might not appreciate Mohammad Asaf’s talents, but someone did.

‘How sad,’ Lizzie said. ‘He made it look beautiful. He didn’t know he was going to die in that very building.’

Sean peered closely, about to correct her that it wasn’t the same block. Asaf had died in Block Two, whereas this was clearly Block Four, but he stopped himself. It would have sounded a bit callous to be that picky and anyway, Eagle Mount Four had its own ghosts. It was the block where the boy had been pushed off ten years ago. He shivered, despite the warmth of the day.

A red fire investigation van drew up and Lizzie put her cup down and walked towards her own car to get her kit.

‘Thanks for the coffee,’ she said, turning back for a moment. ‘Don’t forget your paper.’

She nodded to Maureen’s copy of The Doncaster Free Press, lying on top of the wall. He picked up the newspaper, glancing at the circles and underlinings he’d done earlier. There was something about Mrs Armley that he needed to get clear in his head. If Terry Starkey was her son, where was he living? And I said, there’s someone up to no good. Mrs Armley hadn’t mentioned anyone else, and they’d assumed she meant she was talking to herself, but what if she’d said it out loud, to someone standing by the window with her?

Lizzie was talking to the fire officer, who stood with his arms folded to maximise the bulging muscles crammed into his short-sleeved shirt. She was getting animated. As he got closer, Sean picked up something about procedure and priorities. The fire officer was expressionless, waiting for Lizzie to finish.

‘I can’t let you in there, darling, until we’ve isolated the electrics and I’ll need our specialist guy to come down for that.’

‘Meanwhile the evidence is deteriorating.’ She looked round as Sean approached. The other man glanced at him, trying to decide who, or what, he was.

‘Some people don’t understand protocol,’ he said to Sean, smiling through bleached white teeth.

Lizzie went back to sit on the wall and Sean followed her with a backward glance at the fire officer, who winked at him. If it was meant to be a sign of blokey solidarity, he’d got the wrong man.

‘What a complete tosser,’ Lizzie said. ‘I understand they have their own teams and their own way of doing things, but he’s actually obstructing us now and I’ve got a good mind to report him.’

‘So what are you looking for?’ Sean said.

‘How much do you know?’ She shot him a sideways glance.

‘Almost nothing. Except when the fire was raging I followed a suspect who disappeared into the back of the Health Centre. That same suspect and his sister were here this morning. She got some documents from the flat, but the boy stayed clear.’

‘Has he been charged with anything?’

‘Not as far as I know. Just another ticking off. He collects them.’

‘And you just happened to be here when they turned up?’

‘I was passing. On the way home from my dad’s, as it goes.’

He hoped he hadn’t given himself away. Rick was right about little white lies tying you in knots.

‘The flat’s not part of the crime scene, as far as we’re concerned,’ Lizzie said.

Sean stifled a sigh of relief.

‘Does the CCTV tell us who started the fire?’ he said.

‘Sadly not. There’s a camera on the Health Centre and one on the library, so although you can see people coming and going, there’s a gap in the middle of the parade.’

‘What about mobile phone footage?’

‘Rick Houghton’s on to that. He’s got half his team scouring the Internet. By the time the shop went up in flames, there were over a hundred people here, so there’s bound to be something.’

Sean was wondering what Saleem was up to.

‘Someone should check the appointments at the Health Centre for the day of the fire,’ he said.

‘You’ve lost me.’

‘Saleem might have been running because he saw me, or he might have been running because he had a plan. What if he had an appointment at the Health Centre during the day, to check his stitches or whatever, went to the toilet while he was there and left the window open, ready to squeeze himself in later?’

‘What was he after?’

‘The usual. Prescription drugs to sell on. Anything he could get in his pockets. Living near such an easy source must be quite tempting.’

‘And the fire enabled him to cover his tracks?’

‘Or a happy coincidence,’ Sean said. ‘Perhaps he took the opportunity when he thought nobody would be watching.’

‘You should talk to DCI Khan.’

‘No chance. I’m suspended, remember? You tell him, if you like.’

The fire officer was coming back towards them. Lizzie adjusted her equipment bag on her shoulder and was about to say something, but Sean cut her off.

‘And while you’re at it, tell him someone needs to ask Terry Starkey where he was on the night of Mohammad Asaf’s murder.’

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

Halsworth Grange

Chloe is praying for rain. She rakes the gravel on the path into straight furrows and at every pass wishes she’d had a shower this morning. She lingered too long in bed after her alarm went off, and when she got up there were people moving around. The broken lock on the bathroom door makes it too risky. Now the Icy Mist has worn off and she hates her body’s vinegary odour. If her mother could smell her now, she’d be horrified. She was a woman who moved around in a cloud of perfume, who sprayed the air if it didn’t smell gorgeous enough. Air freshener, beer and fag smoke all mingled together in the pub, but at home it was like a spring meadow, all year long. Well, Chloe smiles to herself, not a real one, not like the meadow here at Halsworth Grange, which prickles the back of your throat with the dry smell of hay and the sweetness of clover. But sometimes she catches the scent her mum wore, on the bus or the train, and she misses her. She looks at the patterns she’s been making with the rake. They’ve gone a bit wobbly. She needs to concentrate. She straightens them up and keeps her distance from the visitors.

After her break, Bill tells her there’s more mowing to do. He jokes about the dodgy haircuts she gave the long grass under the apple trees and she’s relieved he’s not annoyed about her poor mowing in the orchard. He points out a grassy slope next to the car park. It’s like a small field, fenced in from a wild patch of shrubs and trees below. Above it, a dry, brownish lawn is currently laid out with wooden picnic tables.

‘We’ll move the tables down there tomorrow. Give the other patch a rest. Let’s get it as short as we can while it’s clear of visitors and all their rubbish. OK?’

Under her ear defenders the buzz of the ride-on mower seems to be coming from miles away. The vibration through her spine is like the hum of bees. She’s the hive and the bees are inside her. She keeps a straight line, eyes fixed on a fence post at the foot of the field. As she gets close to the edge, she eases off the accelerator and prepares to turn, looping round to make the upward cut. The smell of newly mown grass and engine oil fills her nostrils. At the top of the field, in the existing picnic area, families cluster round tables covered in rubbish. Some of them will make the effort to transfer it to the bins. Some of them won’t. She drops her gaze, focusing on the line she’s following, and turns again.

At the bottom edge of the field another smell drifts across the perfume of grass and oil, but she can’t place it. Once she’s made the turn it fades away behind her. From somewhere in her memory she thinks of a fox’s scent, dark and musty. Maybe it’s something Jay taught her about. There were foxes on the allotment. He taught her so many things about nature. Her Jay, with his flapping coat and wild red hair, smoking a joint or just hanging out in the shed when it rained. He was almost happy there.

Ahead of her a group of teenage girls jump up from their picnic table screaming. They flap pointlessly at a wasp, but Chloe doesn’t care. The rhythm of mowing lulls her into drowsiness. Their screaming barely reaches her through the ear defenders as she steers around another loop and faces back down the slope. Beyond the wooden post-and-rail fencing, rhododendrons as tall as trees have escaped from the formal gardens and run wild. Their season is over and their spent flower heads are browning and sodden. For a moment she wonders if it’s the rotting flowers causing the smell, which is getting stronger and more metallic.

She steers away, back up the field. She’s mown about half the area Bill asked her to cover. It’s satisfying to see the effect of before and after. The thick stripes are neat and orderly, but the lush green of the unmown section, where bumblebees settle on clover heads, is open and free. The picnickers ignore her, even though they have to pause their conversations at the noisy approach of mower. To them she’s just a gardener in a uniform Halsworth Grange hat, part of the furniture, like the ticket sellers or the room guides in the big house. She turns again, coming down the field with the house behind her, and wonders what it must have been like to live here, before the tourists took over. It would have been a laugh to be lady of the manor. She imagines having a butler to wave the wasps off the wicker picnic basket, bottles of champagne and jellies in the shape of rabbits. She sees herself and Jay, in old-fashioned clothes, sitting on deckchairs that don’t fall apart.

Jay cried more after the night they played at being Mr and Mrs Clutterbuck at the allotments. There were new scars on his hands and sometimes bruises on his neck. She never asked any questions, until one day she did and Jay got angry with her, slapped her across the face. It still makes her skin sting to remember it, even though it was years ago. He was sorry he’d slapped her, so sorry that he decided to tell her the truth. After that, their friendship changed forever.

Something causes her to put the brakes on before the next turn: a change of colour in the rhododendron leaves, a darker green in the low-spreading skirts of the shrubs, marking a space, as if a large animal has crashed clumsily into the undergrowth. Chloe stands up on the footrests, immediately cutting off the power to the engine. The silence is sudden and total. In that moment, the light catches an object glittering in the long grass beyond the fence. On the ground, among the thistles, lies a pink sequined sandal.

She looks at it for a long time before she notices her legs are shaking. She sits back on the seat of the mower and takes the ear defenders off. The sandal is out of her line of sight now, but she can’t wipe it from her memory. Inside the sandal was a slim brown foot with painted toes and an ankle leading to a bare leg, but the rest was hidden in a dark green tent of rhododendron.

Someone is screaming and she thinks they must have seen it too, but when she turns round it’s just the girls at the picnic table, laughing and running round, flapping stupidly at the wasps. Under the bushes, flies are buzzing, rising into the light like fighter pilots, before bombing back in for their next raid. She sits on the mower, wanting it to be a fox, wishing she hadn’t seen a sandal and a leg, but unable to change any of it, any more than she is able to move a single muscle in her body. She is still sitting there when Bill comes striding over the field calling her name.

‘Chloe, pet, you OK? Has it run out of juice?’

She knows he can smell it now because he coughs, chokes on the foulness and swears. He comes to a halt by the mower and looks over the fence. He steps forward, his hand over his mouth and nose, tentatively peering into the bushes and then he stops still.

‘Christ. Christ almighty,’ he whispers. ‘It’s that lass. Christ, Chloe, it’s the one who came to see you. What have you done to her?’