Текст книги "Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions"

Автор книги: Guillermo del Toro

Соавторы: Marc Scott Zicree

Жанры:

Публицистика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Sketches of the human brain and heart by del Toro from Notebook 3, Page 3A.

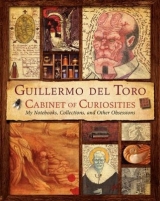

As anyone who has seen MythBusters is aware, I too am obsessed with collecting and re-creating esoteric ephemera from movies and elsewhere, so the chance to visit Bleak House was not to be missed. I discovered, however, that I am an amateur compared to Guillermo. Bleak House is a wonder. We spent hours walking around the various rooms, trading stories, and talking about our obsessions with props and the unobtainable treasures we hope to track down or build one day.

Like Guillermo, I have a strong belief in the talismanic power of objects. Collecting and making movie props is, on one level, a way to connect with the films that inspire me. There’s a power to those objects, and my weird passion for them and the films they’re from is the engine that drives me as a maker and as a man. Feeding those passions is the engine of everything I have. Like the innate drive of the Judas bugs in Mimic, it’s simply in my nature to behave this way.

I think it’s the same for Guillermo. He spends a lot of time at Bleak House painting models and assembling pieces to put on display. Just to have them around, feeding his creativity. For us, it’s an important meditative practice. I get asked, “Why are you doing this?” and all I can say is that if I didn’t do it, I wouldn’t be nearly as happy. I also wouldn’t be me.

Sharing these passions with Guillermo has been a real joy. Since that first visit to Bleak House, we have ended up becoming patrons of each other’s collections. His enthusiasm and generosity are overwhelming and truly infectious to be around. I don’t think I’ve ever been around him when it hasn’t felt like he was having the time of his life.

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 199

* Manny shining shoes in his apartment

* Someone appears by dissolve while walking along.

* Are you drunk? I—uh—oh (looks at the bottle) uh, yeah, this things, the glass is too thick….

* I feel on the verge of tears, explain that 2 me. o/Could you explain to me then, why i—why I

* Shadows on paint puddle MIMIC

* Window shot droplets in FG. Foc.

* Track along a heavy textured wall “a la” nightmare

* MAGIC narrative about images without orig. AUDIO.

* Things that have been set in motion.

* Sometimes I think you don’t care… about anything. About image of someone who is totally distracted

* Chuy looks at a very rare and violent image (Saint Cecilia or Sacred Heart).

* Chinese man with glasses on

• MSZ: The grandfather figure in Mimic is interesting because there’s a resonance with the grandparent/grandchild relationship in Cronos.

GDT: I wanted Federico Luppi to play the character (you can see it in the art), but his English was not very good. When we talked with him, we realized he would have trouble with abundant dialogue. So we had to cut a lot of the vignettes between the grandfather and the grandson in the original screenplay. In one, he said, “This god cannot see,” and he cut his own throat. It was too much for him to see the kid that he loved sort of happily living with the insects. And the grandson didn’t react to the grandfather’s death in the script, which was doubly shocking. They were good ideas, but I don’t know if I would’ve gotten away with them even in the best of circumstances.

MSZ: That’s interesting, because in Cronos, I think of the relationship as the granddaughter observing the grandfather, as opposed to the grandfather watching the grandson.

GDT: I love the idea of somebody watching a loved one doing something unforgivable but still loving them. Or in Hellboy, I love the fact that Liz Sherman comes to terms with who she is by allowing Hellboy to be who he is. I think that’s a very beautiful love story, better than the “Beauty and the Beast” idea of the beast having to look like a prince. Instead, the princess has to accept her own bestiality so the love story can happen.

Jeremy Northam and del Toro on set. It was crucial to del Toro that Northam’s character, Dr. Peter Mann, wear glasses.

“God roach” concept by TyRuben Ellingson.

• GDT: A big, big win for me was that Jeremy [Northam] would wear glasses. The idea was that his character was a scientist—an arrogant guy who thought we could control everything. So then his glasses break, and he cannot go to the optometrist. There was a great line that we shot, when Mira Sorvino was putting the hormones all over Jeremy, and he says, “All I need is a pair of pliers.” And the problem is that they’re under the sink at home. And it just gives you an instant idea of how screwed they are. They are close to home, but the pair of pliers is just so far away. He might as well be in Moscow.

MSZ: Looking at your later work, a strong motif is the absence of eyes, including the covering up of eyes with lenses.

GDT: I like the idea, maybe because I wear glasses. But the most effective use of glasses is in Lord of the Flies, with Piggy and his broken glasses. And then you have Battleship Potemkin. Broken glasses are just a great image of downfall for me. I use it again and again. Or an aneurysm in a single eye—I love bloodshot eyes, but only on one side.

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 205

* A counterfeiter quit. He couldn’t make enough money.

* LOTTIE watches Marty dance by himself.

* Martyn has an archive on LOTTIE.

* Sheets FLOAT in pool with Ray

* Ben Van Os: Orlando, Macon, Vince & Theo

* Dennis Gassner: B. Fink, Miller’s Crossing.

Jeremy’s broken glasses

* Blind, he gropes along the wall.

* No end to doubting.

* MUSIC OVER image in silence and slo-mo.

* There is no end to doubting Martyn

* Boot

* WATER drips through old planks.

* Bewitched, MARTYN watches his heater (or the hospital’s)

Electric resistance

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 206

Del Toro wanted the human authorities that secure the subway to wear gas masks, rendering them disturbingly similar in appearance to the mimics.

Keyframe elaborating on this resemblance by TyRuben Ellingson.

• MSZ: What was this image of the crutch for [opposite, top]?

GDT: I’d been wanting to do an artificial limb since Cronos, to show the inhuman elements of a human character. I like the idea of showing how imperfect mankind is. The insects in Mimic were all organic, but mankind needed glasses, artificial limbs. The mimics are the perfect ones; not us.

That’s why I tried to populate the church with statues covered in plastic, almost cocooned, like the eggs of a cockroach, which are translucent. I work instinctively by finding elements that rhyme, and I just organize them in my movies as elements that echo each other, not necessarily intellectualizing the resemblances. I think that the whole of art can be summed up in the two concepts of symmetry and asymmetry. And I am very attracted to playing with both. I love symmetric images. But I also love the asymmetry of a design, like one broken glass, one bloodshot eye, one missing arm.

On Mimic, I was very into symmetry and wanted to have the guys who secure the place, the ones who wear the gas masks, look a little like the insects. So here you see me playing with that visual rhyme and the question of who is more human, the insects or the guys? Then there is this composition where I put Chuy between two insects. It’s like the Holy Trinity of the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit. I wanted to put Chuy in the middle and make it look like a religious icon of a holy family of the future.

THE DEVIL’S BACKBONE

Illustration from Jaime’s sketchbook by Tanja Wahlbeck.

The ghost Santi (Andreas Muñoz).

Sketch of Santi by del Toro.

Storyboard illustrations of Santi.

The undetonated bomb by Carlos Gimènez.

“I WANT TO DO A FILM ABOUT SOME KIDS in an orphanage during the Spanish Civil War—and oh yeah, one of them’s dead.” So Guillermo describes his studio pitch for The Devil’s Backbone (2001), and one would be hard-pressed to think up a synopsis less likely to enthuse a Hollywood executive. However, with The Devil’s Backbone, Guillermo planted his flag, declaring himself something other than a Tinseltown work-for-hire—he was a true writer-director.

After the disappointment of Mimic, Guillermo felt certain such a distinction was a moot point for him. His career, he thought, was over. “Pedro Almodóvar resurrected me from the dead after Mimic,” Guillermo says. “He gave me a chance at life again.”

They had met some years earlier during the Miami International Film Festival. “I was standing on a balcony near the pool at the hotel, when I heard a voice from the next room over saying to me, ‘Are you Guillermo del Toro?’ I turned, and he said, ‘I’m Pedro Almodóvar. I love Cronos, and I would love to produce your next movie.’

“Years later, I called him to do The Devil’s Backbone, and the movie saved my life. Pedro Almodóvar gave me a second chance in film and in life. He was absolutely hands-off, protecting me, giving me everything I needed to make the movie I needed to make, and not having the least amount of ego.”

Guillermo had actually written a version of The Devil’s Backbone years earlier, before Cronos. He was in his early twenties, learning his craft from filmmaker Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, but Hermosillo destroyed the draft. At the time, Guillermo decided to pursue Cronos rather than re-create the lost screenplay.

In the end, the extended gestation of The Devil’s Backbone resulted in a wonderful film. “Depending on the week, I like it as much or more than Pan’s Labyrinth, never less,” notes Guillermo. “I seriously think it’s the best work I’ve ever done. It is not a visually flamboyant movie, but it’s incredibly minutely constructed visually. Pan’s Labyrinth is more like pageantry; it is very gorgeous to look at. But I think Devil’s Backbone is almost like a sepia illustration.”

In The Devil’s Backbone, Guillermo explores his personal past and present, coming to conclusions about where he has been, who he has been, and who he chooses to be as an artist. Some of Guillermo’s core themes come to stark clarity in his third feature: heroes and villains defined by their actions, their choices, and how far they will go; restraint as a value held in high esteem, as in Cronos; and holding on to one’s sense of self in the face of evil, desperation, and despair, as later epitomized in Pan’s Labyrinth.

In addition, a fascinating breed of villain specific to Guillermo’s films emerges. “I love the character of the fallen prince. Jacinto, the villain in The Devil’s Backbone, is a fallen prince. I can completely relate to Nomak in Blade II, because he’s a fallen prince. In Hellboy II, the main villain is a fallen prince. And I think, to a certain degree, the captain in Pan’s Labyrinth is a fallen prince. He’s a guy that has the shadow of his father suffocating him.”

Exiled princesses also figure in Guillermo’s films, but as heroines, not villains. This figure is exemplified by Ofelia in Pan’s Labyrinth, Nyssa in Blade II, and Princess Nuala in Hellboy II.

Guillermo’s ability to sympathize with his villains in no way mitigates or excuses their actions. “Because, the fact is, there are people in this world that are fragile inside, God knows, but 100 percent of their actions are antisocial,” Guillermo adds. “There are guys that truly may have a hurting child inside, but they’re stabbing, gouging, raping, and robbing everything that crosses their path. And whoever thinks that’s not true has probably encountered evil a lot less than I have.”

Guillermo’s notebook pages show him working through some of the most iconic images in The Devil’s Backbone, in particular the murdered ghost. This starts out as a dead caretaker who looks rather like Lurch in The Addams Family and ends up a sad child with white-irised black eyes and cracked porcelain skin—perhaps the most beautiful, disturbing ghost in all of cinema. We also find the unexploded bomb and the supersaturated gold and blue lights illuminating the long stone corridors.

These pages also reveal a rare personal note from Guillermo, who takes pains to point out that these notebooks are “not really diaries.” However, bits and pieces from his private life do creep in occasionally. Guillermo writes of his parents, “I’ve found that simply being with my father is two hundred times better than speaking with him. My mom, on the other hand, is extremely intelligent. She’s my soul mate. Even in her sins.”

And as usual, the notebook contains Guillermo’s ruminations on a number of other ongoing and future projects, most notably Hellboy. “People say, ‘You juggle too much stuff.’ I tell them, ‘It’s always been like that, except now it’s public.’ Back in the day I was doing Devil’s Backbone, I was preparing Hellboy, and I was working already on ideas for Blade II. At the same time I was trying to polish a screenplay called Mephisto’s Bridge, and I was writing The Left Hand of Darkness.”

Through all this juggling of images and notes, some destined for other projects and some left to dwell in the realm of private reverie, the notebook pages for The Devil’s Backbone chart Guillermo’s return to himself—to valuing his own beliefs, his aesthetic, his voice. With The Devil’s Backbone, Guillermo moved beyond the removable pages of a Day Runner. He self-consciously recorded his thoughts in a more permanent fashion, turning them into works of art within the pages of a totemic book marked by his signature style.

Illustration from Jaime’s sketchbook by Tanja Wahlbeck.

Concept of Santi by Guy Davis for the Bleak House collection.

Jaime (Iñigo Garcès) caresses the unexploded bomb.

Storyboard illustrations by Carlos Gimènez.

Part of the set for Dr. Casares’s laboratory.

Storyboard illustration by Carlos Gimènez.

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 40

G* He was a doddering, sickly old man. With the crisis he gets better and moves up in the world.

G* Someone is watching soap operas and reacts to everything he sees (it would be better if this character is a villain).

* A hand shaped like a crab’s claw.

G* Speak with the portrait of their departed.

G* Where did I put my glasses? They’re on your forehead.

* THE OLD MAN WITH THE NEEDLE

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 41

*The Scene of Christ

E* He who made an offering and merged with the tree saw the dead ones pass by as they returned.

E* In the middle of the night, he looks to one side and prays, whatever they do to you don’t turn around or answer them. (The one who’s listening is hidden)

E* Beings who are red from head to foot.

E* Hey! I bet Juan is there!

E* The warlocks remove their own eyes and then someone burns them.

E* That’s what people say; the story is over.

• GDT: The original Devil’s Backbone had this character that was this old man with a needle, which is really a terrifying character that one day I’ll do. And here [above] is essentially the operation of the ghost in Devil’s Backbone, at the end of a corridor, except in the original here it was Jesus Christ, which makes a big difference.

NOTEBOOK THOUGHTS FROM ABROAD

NEIL GAIMAN

THE FIRST TIME I met Guillermo del Toro, I was in Austin, Texas, and he sent for me. I have no idea how he arranged it: It was, in truth, all rather dreamlike. I know that I was there to present a film, and suddenly I was in Guillermo’s house, and he and his wife were feeding me a magnificent lunch (she is a remarkable cook). Along with his wife I met his little daughters, and then, in the manner of dreams, he was showing me around his man cave, introducing me to the statues and the props, the pages of original art I knew from my childhood by Bernie Wrightson or Jack Kirby, the beautiful things and the grotesques and the things that inhabited the places where beauty and grotesquery collapse into something peculiar and singular and new. Guillermo delighted in pointing out all the strange and nightmarish treasures he had gathered and telling me their history.

Del Toro’s drawing of a stick bug from Notebook 4, Page 3B.

And then, when I thought I could no longer be impressed by anything else, he showed me his notebooks and I began to marvel anew.

Once it was all over (I do not, I admit, remember who took me away from that place or where I went), I could not entirely recall the contents of the notebooks. I remembered colors and faces and words and clockwork and insects and people and nothing more. The feeling of dreaming intensified. If ever anyone had brought anything back from the place where we dream, those notebooks were it.

The next time that I spent really good, quality time with Guillermo, we were in Budapest, Hungary, a dreamlike place in its own right, and his daughters were ten years older and his wife had not aged a day. I stayed with him for many days, shadowing him on the set of Hellboy II. He let me listen when he talked to actors. He let me understand each decision he made. I learned so much about making movies and I learned so much about Guillermo del Toro: how he did what he did, why he does what he does. He told me of making monster TV shows in Mexico when he was young. He played the monsters. Of course he did, I thought.

He showed me his notebooks, and this time I understood more of what I was seeing. He explained the way he chose a specific palette for each film. He would start with colors; the colors that would become the keynotes for the film. There were words. There were drawings and paintings, so haunting, so resonant. It was as if Guillermo had made a secret film, and that everything the audience would ever see was only the innocent, jutting-out top of an iceberg. They would never know how huge the Titanic-sinking world beneath was; the world of Guillermo’s imagination, filled with fairies and demons and insects and clockwork—always clockwork.

Often I suspected that the true art, the place the real magic lived and lurked, was in those notebooks, because the stories in them seemed infinite, fragmentary, perfect. And if I was sure of anything, it was that nobody would ever see the notebooks, because the notebooks took you backstage, into another world. One of the world’s rarest and oddest books is the Codex Seraphinianus. I found a copy in a rare bookstore in Bologna in 2004, having looked for it for years. The Codex Seraphinianus is a strange book written in unreadable code-like writing, filled with pictures that almost make sense, and reading it is like dreaming while awake. Guillermo’s notebooks are stranger than that.

My conversation with Guillermo feels like it began, in a dream, in Austin fifteen years ago and continues, in the manner of dreams, in strange places across the world. The last time we spoke, unless I dreamed it, we were in Wellington, New Zealand, in a café, and we talked about everything under the sun. We were older, and the food was not as good as the food that Guillermo’s wife cooks, but we were the same people as when we first met; even if, these days, I have had a secret pocket sewn into my jacket to allow me always to carry a notebook of my own.

NOTEBOOK 3, PAGE 16B

– Use objects in the foreground to create black “wipes” for a continuous dolly shot and change the angle during the shot!!

Brick archways painted white and black ironwork.

Window is a CURVING SHAFT.

“Window” is really a curved shaft.

See EdTV in Austin with Robo.

–1645 Mary Kings Close Bubonic Plague

All residents are bricked in there and died of hunger and disease. No food. Local butchers were hired to quarter and dispose of the corpses. This happened on a street in Edinburgh (according to the frightful bartender upstairs) called “Mary Kings Close.” The residents of this street were infected with the bubonic plague. A decision was made to seal the street off with brick walls and let the people inside die from starvation and the cold. They weren’t given water or food

18:43 seated p. EdTV in the Paramount.

• GDT: This is me trying to find a look for the ghost in The Devil’s Backbone. And there were many, many different iterations of the story. There was an iteration where the ghost was the caretaker. It was an adult character. Because there was a version where they killed the caretaker halfway through the film with the lances, like a mammoth, and then he came back as a ghost. With many projects, you’re talking two or three years, and you go through many, many things that don’t make it. So this [above] was the rendering of the caretaker as a ghost, and it’s already veering away from a real corpse in that it’s really desiccated, and it has some of the features of the final ghost, with its black eyes and clear irises, but it is not yet porcelain.

NOTEBOOK 3, PAGE 13B

The boy ghost from “The Devil’s Backbone” is semi-translucent.

–Rasputin’s rules are: No more lives for nothing. Our sole purpose is to feed the gods. R. wears dark glasses

–Throws something in the air and Hellboy catches it. When he looks back, he/she’s already gone.

–Rasputin died in 1916: cyanide, gunshots with steel bullets. He froze to death.

–I will not burn alone…”

–R. doesn’t have eyes. They’re made of glass.

–Art is always changing, the world just repeats itself…

–Morgue filled with frogs…

–Behind his “eyes,” R. has a web of tissue in constant motion…

–We’ve bred a brand new world of couch potatoes.

–He makes Liz angry so that she’ll explode.

–Rasputin 30-meg 100 of square miles of pine forest: ball of fire, black clouds, black rain. Glowing clouds June 30 1908.

• MSZ: So now, is this [above] The Devil’s Backbone? Because I noticed a similarity, but I wasn’t sure what you were illustrating.

GDT: At this point, I didn’t know exactly what the story of The Devil’s Backbone was going to end up being. In one incarnation or another, it had been with me since the 1980s, when I first wrote it. And then I attempted it again in 1993, after Cronos. So it was something I had been working on for over a decade. This is just one attempt, then, at the ghost of The Devil’s Backbone.

I had been toying with the idea of a translucent ghost for a long time. I wanted to do a heat distortion around the ghost, and I wanted to see the ribs, and the femur, and the pelvic bone. There was also this idea of it being framed by a door. I really don’t know if I was thinking of a teardrop shape, or a Gothic door that is out of whack in a crumbling building.

MSZ: How did you eventually pull off that translucency?

GDT: Ultimately we were able to do it fairly easily because by the time I shot the movie, CG was much more advanced. So what we did is we made the bones visible only when he crosses a haze of light, a little ray, a little beam of life. And they were able to animate a skeleton inside of the body.

MSZ: And the blood coming out of the ghost in the final film, was that also CG?

GDT: That came later. Originally I wanted the distortion in the air, like shimmering, and that’s what the drawing indicates. But a little later I came up with the idea that he had drowned with the injury to his head. The blood was easier to produce with particle effects.

I really wanted him to look like porcelain. Here [opposite] he is still a corpse, but then one day I said, “Well, why doesn’t he look like a broken doll?” Because it doesn’t have to make sense. And DDT, the effects guys, they really, really resisted the idea. They wanted very much to do a rotting corpse, and I understood them, as sculptors and all that, I understood their impulse.

MSZ: It goes back to an idea we’ve talked about previously, which is that every really great monster is beautiful. Grotesque and beautiful.

BLUE NOTEBOOK PAGE 145

* M.C. perhaps [?] with paint by HAND on the rock. Cave painting.

* Rain of burning ash in slow motion.

* Jose Maria Velazco’s slow journey through the sky until discovering the [?] there in the distance with a cloud of dust.

* The apparition of little Joey.

* Valley of Geysers/Holy waters in the desert M.C.

* Pigeons/bats in the marina-cave, support with a very strong beam of light.

* M.C.’s cell slowly consumed by the dusk’s lengthening shadows.

* “Raging sea” scenes after this shot EVERYTHING in slow motion.

Close view of the sculpt of Santi’s face created by DDT, based on del Toro’s notebook illustration

• MSZ: So here [opposite] is a drawing of Santi, a more elaborate one.

GDT: You can see how it evolves. The first one featured a crumbling edifice, or another alternative was for there to be a curtain. But I wanted something that felt womblike, like the fetus in the jar, the baby in the womb, the kid in the pool, amniotic fluid, amber water, all that stuff.

MSZ: So how did the design evolve from here?

GDT: I sent this drawing to DDT. You can see now the eyes are black, the iris is white. Now he’s a porcelain doll. And DDT and I made a very long chain of emails, sending drawings and literally, literally counting the number of cracks. I would say, “Take this one out, put one over here.” We art directed exactly the number of cracks, exactly the position of the tear.

You know, I say to people, “We deliberately made the ghost a figure that evokes things that are fragile.” And there are echoes in the movie: the shell of an egg, the broken porcelain of a childhood doll, and it has tears of rust. I mean, it’s a crying ghost. All those things are meant to evoke your sympathy rather than your terror. The ghost can function as a horrifying figure only very briefly in the beginning, but then, by repeatedly showing him, it becomes clearer and clearer that he is not a pernicious presence.

And the heart at the bottom is from Blade II, which you can see only in the outtakes. Then, because it didn’t make it into the release of Blade II, I took it and put it in The Strain.

But in another way, the jar ended up being the jar of tears in Hellboy. That’s exactly the design of the jar. I remember reading Raymond Chandler in his entirety and realizing that he cannibalized his stories. He would take a paragraph from his first detective, who was called John Dalmas, and he would reuse that paragraph, and make it better, like fifteen years later. He’d change one comma, or one adjective, and it was completely different. And I always think I have a similar way of cannibalizing ideas over and over.

The ghost (Andreas Muñoz) as he appears in the film.

NOTEBOOK PAGE 23

Santi in The Devil’s Backbone

Damaskinos keeps his heart preserved in a small glass urn. Sometimes he looks at it to remember what it was like to feel. He now lives in a stainless-steel funeral chamber kept at 0° centigrade

NOTEBOOK 3, PAGE 21A

–Hellboy calls Liz to read her a letter he wrote. He goes for a coffee with Mayers.

–The story’s basic triangle in Hellboy is that of the student who falls in love with his teacher’s wife. Hellboy is, above all, a noble and primitive guy.

–How difficult it is to talk with Spaniards about The Devil’s Backbone. It’s easier for me to chat in English than in the Spanish spoken in Spain, the motherland. That said, I’m confident that the fable is universal. The characters are really, really iconic: Luppi with his “black” hair, his little tie, and his handkerchief, is the old, impotent dandy. Marisa, blonde, dressed in black, with two canes and yellow glasses. The children all in uniform, the school made up of arches, the empty, dead landscape. And God, like the sun, screws everything up, and completely burns everything He doesn’t.

–I’ve found that simply being with my father is 200 times better than speaking with him. My mom, on the other hand, is extremely intelligent. She’s my soul mate. Even in her sins.

The undetonated bomb, illustrated by del Toro in his notebook and as it appears in Jaime’s sketchbook.

• MSZ: So now we come to this page [opposite] with the bomb from The Devil’s Backbone. You write, “How difficult it is to talk with Spaniards about The Devil’s Backbone. It’s easier for me to chat in English than in the Spanish spoken in Spain, the motherland. That said, I’m confident that the fable is universal. The characters are really, really iconic: Luppi with his ‘black’ hair, his little tie, and his handkerchief, is the old, impotent dandy.”

GDT: What is funny is all that went away. I wanted Luppi, like Professor Aschenbach in Death in Venice, to have black hair that he put shoe polish on, because I wanted him to be bleeding black, and because I wanted him to be really fastidious about his appearance. And that’s in the movie. He’s very fastidious. He presses his ties with books. But we made a budget, and we made a schedule, and we started breaking it down, accounting for the cleanup time with bleeding hair versus not-bleeding hair. And it went away.

The moment we started color-coding the movie, I realized Marisa’s hair needed to be red, not blonde, and that’s because the color of the school, the mosaic, and the doors, would look really, really narrow if you had a blonde. Then I said, “I’m gonna give her only one wooden leg, so I’ll give her one single cane.”

Everything evolves. It was the same thing with the kids. We started thinking about school uniforms. But with the reality of the Civil War, we found that uniforms would exist only in a private school. So out they went. And the only thing that remains is God and the sun.

The same with Hellboy. Here I wrote, “The story’s basic triangle in Hellboy is that of the student who falls in love with his teacher’s wife. Hellboy is, above all, a noble and primitive guy.” There was a time when there was a different story for Hellboy.

MSZ: What about this great image of the little boy with the bomb?

GDT: An earlier incarnation of the bomb was that I wanted it to be rotting in such a way that you could see the mechanism inside. And then you do research and realize that’s impossible, and you go, “Oh, all right.” The only thing that remains of that, which is a complete fantasy, is that it ticks.

MSZ: So what was the research that proved that you couldn’t show the mechanism?

GDT: We started doing the research, and the bombardment in the Civil War was done by the Condor Legion, which were German planes, and they were testing blanket bombing in Spain. And the bombs were very small. I mean, size-wise, they were very small. But I had this image in my head of the American blanket bombings and Dr. Strangelove, with a giant bomb and the dropper. So it’s inaccurate. The planes were not able to have that dropping system. And I said, “You know what? To hell with it. It’s a great image.”