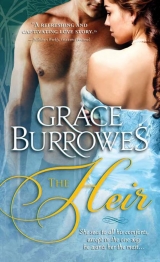

Текст книги "The Heir"

Автор книги: Grace Burrowes

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

As the night settled peacefully into his bones, he closed his eyes and started making a list.

Anna was up early enough the next morning to see to her errand, one she executed faithfully on the first of each month—rain, shine, snow, or heat. She sat down with pen, plain paper, and ink, and printed, in the most nondescript hand she could muster, the same three words she had been writing each month for almost two years: All is well. She sanded that page and let it dry while she wrote the address of an obscure Yorkshire posting inn on an envelope. Just as she was tucking her missive into its envelope, booted footsteps warned her she would soon not have the kitchen to herself.

“Up early, aren’t you, Mrs. Seaton?” the earl greeted her.

“As are you, my lord,” she replied casually, sliding the letter into her reticule.

“I am off to let Pericles stretch his legs, but I find myself in need of sustenance.”

“Would you like a muffin, my lord? I can fix you something more substantial, or you can take the muffin with you.”

“A muffin will do nicely, or perhaps two.” He narrowed his eyes at her. “You aren’t going to be shy with me, are you, Mrs. Seaton?”

“Shy?” And just like that, she blushed, damn him. “Why ever would I…? Oh, shy. Of course not. A small, insignificant, forgivable indiscretion on the part of one’s employer is hardly cause to become discomposed.”

“Glad you aren’t the type to take on, but I would not accost you where someone might come upon us,” the earl said, pouring himself a measure of lemonade.

“My lord,” she shot back, “you will not accost me anywhere.”

“If you insist. Some lemonade before you go out?”

“You are attempting to be charming,” Anna accused. “Part of your remorse over your misbehavior last evening.”

“That must be it.” He nodded. “Have some lemonade anyway. You will go marching about in the heat and find yourself parched in no time.”

“It isn’t that hot yet,” Anna countered, accepting a glass of lemonade, “And a lady doesn’t march.”

“Here’s to ladies who don’t march.” The earl saluted with his drink. “Now, about those muffins? Pericles is waiting.”

“Mustn’t inconvenience dear Pericles,” Anna muttered loudly enough for the earl to hear her, but his high-handedness did not inspire blushes, so it was an improvement of sorts. She opened the bread box—where anybody would have known to look for the muffins—and selected the two largest. The earl was sitting on the wooden table and let Anna walk up to him to hand over the goodies.

“There’s my girl.” He smiled at her. “See? I don’t bite, though I’ve been known to nibble. So what is in this batch?”

“Cinnamon and a little nutmeg, with a caramel sort of glaze throughout,” Anna said. “You must have slept fairly well.”

Now that she was close enough to scrutinize him, Anna saw that the earl’s energy seemed to have been restored to him. He was in much better shape than he had been the previous evening, and—oh dear—the man was actually smiling, and at her.

“I did sleep well.” The earl bit into a muffin. “And he is dear, you know. Pericles, that is. And this”—he looked her right in the eye—“is a superb muffin.”

“Thank you, my lord.” She couldn’t help but smile at him when he was making such a concerted effort not to annoy her.

“Perhaps you’d like a bite?” He tore off a piece and held it out to her, and abruptly, he was being very annoying indeed.

“I’ll just have one of my own.”

“They are that good, aren’t they?” the earl said, popping the bite into his maw. “Where do you go this early in the morning, Mrs. Seaton?”

“I have some errands,” she said, pulling a crocheted summer glove over her left hand.

“Ah.” The earl nodded sagely. “I have a mother and five sisters, plus scads of female cousins. I have heard of these errands. They are the province of women and seem to involve getting a dizzying amount done in a short time or spending hours on one simple task.”

“They can,” she allowed, watching two sizeable muffins meet their end in mere minutes. The earl rose and gave her another lordly smile.

“I’ll leave you to your errands. I am fortified sufficiently for mine to last at least until breakfast. Good day to you, Mrs. Seaton.”

“Good day, my lord.” Anna retrieved her reticule from the table and made for the hallway, relieved to have put her first encounter of the day with his lordship behind her.

“Mrs. Seaton?” His lordship was frowning at the table, but when he looked up at her, his expression became perfectly blank—but for the mischief in his eyes.

“My lord?” Anna cocked her head and wanted to stomp her foot. The earl in a playful mood was more bothersome than the earl in a grouchy mood, but at least he wasn’t kissing her.

He held up her right glove, twirling it by a finger, and he wasn’t going to give it back, she knew, unless she marchedup to him and retrieved it.

“Thank you,” she said, teeth not quite clenched. She walked over to him, and held out her hand, but wasn’t at all prepared for him to take her hand in his, bring it to his lips, then slap the glove down lightly into her palm.

“You are welcome.” He snagged a third muffin from the bread box and went out the back door, whistling some complicated theme by Herr Mozart that Lord Valentine had been practicing for hours earlier in the week.

Leaving Anna staring at the glove—the gauntlet?—the earl had just tossed down into her hand.

“Good morning, Brother!”

Westhaven turned in the saddle to see Valentine drawing his horse alongside Pericles.

“Dare I hope that you, like I, are coming home after a night on the town?” Val asked.

“Hardly.” The earl smiled at his brother as they turned up the alley toward the mews. “I’ve been exercising this fine lad and taking the morning air. I also ran into Dev, who seems to be thriving.”

“He is becoming a much healthier creature, our brother,” Val said, grinning. “He has this great, strapping ‘cook/housekeeper’ living with him. Keeps his appetites appeased, or so he says. But before we reach the confines of your domicile, you should be warned old Quimbey was at the Pleasure House last night, and he said His Grace is going to be calling on you to discuss the fact that your equipage was seen in the vicinity of Fairly’s brother yesterday.”

“So you might ply his piano the whole night through,” Westhaven said, frowning mightily at his brother. Val grinned back at him and shook his head, and Westhaven felt some of his pleasure in the day evaporating in the hot morning air. “Then what is our story?”

“You have parted from Elise, as is known to all, so we hardly need concoct a story, do we?”

“Valentine.” Westhaven frowned. “You know what His Grace will conclude.”

“Yes, he will,” Val said as he dismounted. “And the louder I protest to the contrary, the more firmly he’d believe it.”

Westhaven swung down and patted Pericles’s neck. “Next time, you’re walking to any assignation you have with any piece of furniture housed in a brothel.”

They remained silent until they were in the kitchen, having used the back terrace to enter the house. Val went immediately to the bread box and fished out a muffin. “You want one?”

“I’ve already had three. Some lemonade, or tea?”

“Mix them,” Val said, getting butter from the larder. “Half of each. There’s cold tea in the dry sink.”

“My little brother, ever the eccentric. Will you join me for breakfast?” Westhaven prepared his brother’s drink as directed then poured a measure of lemonade for himself.

“Too tired.” Val shook his head. “I kept an eye on things at the Pleasure House until the wee hours then found myself fascinated with a theme that closely resembles the opening to Mozart’s symphony in G minor. When His Grace comes to call, I will be abed, sleeping off my night of sin with Herr Mozart. You will please inform Papa of this, and with a straight face.”

His Grace presented himself in due course, with appropriate pomp and circumstance, while Val slept on in ignorant bliss above stairs. The footman minding the door, cousin to John, knew enough to announce such an important personage, and did so, interrupting the earl and Mr. Tolliver as they were wrapping up a productive morning.

“Show His Grace in,” the earl said, excusing Tolliver and deciding not to deal with his father in a parlor, when the library was likely cooler and had no windows facing the street. Volume seemed to work as well as brilliance when negotiating with his father, but sheer ruthlessness worked best of all.

“Your Grace.” The earl rose and bowed deferentially. “A pleasure as always, though unexpected. I hope you fare well?”

“Unexpected.” His Grace snorted, but he was in a good mood, his blue eyes gleeful. “I’ll tell you what’s unexpected is finding you at a bordello. Bit beneath you, don’t you think? And at two of the clock on a broiling afternoon! Ah, youth.”

“And how is Her Grace?” the earl asked, going to the sideboard. “Brandy, whiskey?”

“Don’t mind if I have a tot,” the duke said. “Damned hot out, and that’s a fact. Your mother thrives as always in my excellent and devoted care. Your dear sisters are off to Morelands with her, and I was hoping to find your brother here so I might dispatch him there, as well.”

The earl handed the duke his drink, declining to drink spirits himself at such an early hour.

The duke sipped regally at his liquor. “I suppose if Valentine were about, I’d be hearing his infernal racket. Not bad.” He lifted his glass. “Not half bad, after all.”

Mrs. Seaton’s words returned to the earl as he watched his father sipping casually at some of the best whiskey ever distilled: You fail to offer a civil greeting upon seeing a person first thing in the day… You can’t be bothered to look a person in the eye when you offer your rare word of thanks or encouragement…

And it hit him like a blow to the chest that as much as he didn’t want to be the next Duke of Moreland, he very especially did not want to turn into another version of thisDuke of Moreland.

“If I see Val,” Westhaven said, “I will tell him the ladies are seeking his company at Morelands.”

“Hah.” The duke set aside his empty glass. “His mother and sisters, you mean. They’re about the only ladies he has truck with these days.”

“Not so,” the earl said. “He is much in demand as an escort and considered very good company by many.”

The duke heaved a martyr’s sigh. “Your brother is a mincing fop, but word is you at least had him in hand at Fairly’s whorehouse. Have to ask, how you’d do it?”

Now that was rare, for the duke to ask a question to which he sought an answer. Westhaven considered his reply carefully.

“I had heard Fairly has an excellent new Broadwood on the premises, which, in fact, he does.” A truth, as far as it went.

“So all I have to do,” the duke said with sudden inspiration, “is find some well-bred filly of a musical nature, and we can get him leg-shackled?”

“It might be worth considering, but I’d be subtle about it, ask him to escort Her Grace to musicales, for example. He won’t come to the bridle if he sees your hand in things.”

“Damned stubborn,” His Grace pronounced. “Just like his mama. A bit more to wet the whistle, if you please.” Westhaven brought the decanter to where his father sat on the leather couch, and poured half a measure into the glass. On closer inspection, the heat was taking a toll on His Grace. His ruddy complexion looked more florid than usual, and his breathing seemed a trifle labored.

“Speaking of stubbornness,” the earl said when he’d put the decanter back on the sideboard, “I no longer have an association with the fair Elise.”

“What?” His Grace frowned. “You’ve lost your taste for the little blonde?”

“I wouldn’t say I’ve lost my taste for the little blonde, so much as I’ve never had a taste for my privacy being invaded nor fancied the Moreland title going to somebody who lacks a drop of Windham blood.”

“What are you blathering on about, Westhaven? I rather liked your Elise. Seemed a practical woman, if you know what I mean.”

“Meaning she took your bribe, or your dare,” the earl concluded. “Then she turned around and offered her favors elsewhere, to at least one other tall, green-eyed lordling that I know of, and perhaps several others, as well.”

“She’s a bit of a strumpet, Westhaven, though passably discreet. What would you expect?” The duke finished his drink with a satisfied smack of his lips.

“She’s Renfrew’s intended, if your baiting inspired her to get with child, Your Grace,” the earl replied. “You put her up to trying to get a child, and the only way she could do that was to pass somebody else’s off as mine.”

“Good God, Westhaven.” The duke rose, looking pained. “You aren’t telling me you can’t bed a damned woman, are you?”

“Were that the case, I would not tell you, as such matters are supposedto be private. What I am telling you is if you attempt to manipulate one more woman into my bed, I will not marry. Back off, Your Grace, or you will wish you had.”

“Are you threatening your own father, Westhaven?” The duke thumped his glass down, hard.

“I am assuring him,” the earl replied softly, “if he attempts even once more to violate my privacy, I will make him regret it for all of his remaining days.”

“Violate your…? Oh, for the love of God, boy.” The duke turned to go, hand on the door latch. “I did not come here to argue with you, for once. I came to tell you it was well done, getting your brother to Fairly’s, reminding him what… Never mind. I came with only good intentions, and here you are threatening me. What would your dear mama think of such disrespect? Of course I am concerned; you are past thirty, and you have neither bride nor heir nor promise thereof. You think you can live forever, but you and your brother are proof that even when a man has decades to raise up his sons, sometimes the task is yet incomplete and badly done. You aren’t without sense, Westhaven, and you at least show some regard for the Moreland consequence. All I want is to see the succession secured before I die, and to see your mother has some grandchildren to spoil and love. Good day.”

He made a grand, door-slamming exit and left his son eyeing the decanter longingly. When a soft knock came a few minutes later, the earl was still so lost in thought, he barely heard it.

“Come in.”

“My lord?” Mrs. Seaton, looking prim, cool, and tidy, strode into the room and gave him her signature brisk curtsy. “The luncheon hour approaches. Shall we serve you on the terrace, in the dining parlor, or would you like a tray in here?”

“I seem to have lost my appetite, Mrs. Seaton.” The earl rose from his desk and walked around to sit on the front of it. “His Grace came to call, and our visit degenerated into its usual haranguing and shouting.”

“One could hear this,” Mrs. Seaton said, her expression sympathetic. “At least on His Grace’s part.”

“I was congratulated on dragging my little brother to a brothel, for God’s sake. The old man would have fit in wonderfully in days of yore, when bride and groom were expected to bed each other before cheering onlookers.”

“My lord, His Grace means well.”

“He will tell you he does,” the earl agreed. “Just being a conscientious steward of the Moreland succession. But in truth, it’s his own consequence he wants to protect. If I fail to reproduce to his satisfaction, then he will be embarrassed, plain and simple. It’s not enough that he sired five sons, three of whom still live, but he must see a dynasty at his feet before he departs this earth.”

Mrs. Seaton remained quiet, and the earl recalled he’d sung this lament in her hearing before.

“Is my brother asleep?”

“He is, but he asked to be awakened not later than two of the clock. He wants to put in his four hours before repairing again to Viscount Fairly’s establishment.”

“I do believe my brother is studying to become a madam.”

Again, his housekeeper did not see fit to make any reply.

“I’ll take a tray out back,” the earl said, “but you needn’t go to all the usual bother… setting the table, arranging the flowers, and so forth. A tray will do, as long as there’s plenty of sweetened lemonade to go with the meal.”

“Of course, my lord.” She bobbed her curtsy, but he snaked out a hand to encircle her wrist before she could go.

“Are you unhappy with me?” he asked, eyeing her closely. “Bad enough His Grace finds fault with me at every turn, Mrs. Seaton. I am trying very hard not to annoy my staff as much as my father annoys me.”

“I do not think on your worst day you could be half so annoying to us as that man is to you. Your patience with him is admired.”

“By whom?”

“Your staff,” she replied. “And your housekeeper.”

“The admiration of my housekeeper,” the earl said, “is a consummation devoutly to be wished.”

He brought her wrist to his lips and kissed the soft skin below the base of her thumb, lingering long enough that he felt the steady beat of her pulse.

She scowled at him, whirled, and left without a curtsy.

So much, the earl thought as he watched her retreat, for the admiration of his housekeeper.

Four

“I NEVER DID ASK IF YOU SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETED your errands this morning.” Westhaven put aside his copy of The Timesas Anna set his lunch tray before him.

“I did. Will there be anything else, my lord?”

He regarded her standing with her hands folded, her expression neutral amid the flowers and walks of his back garden.

“Anna,” he began, but he saw his use of her name made her bristle. “Please sit, and I do mean will you please.”

She sat, perched like an errant schoolgirl on the very edge of her chair, back straight, eyes front.

“You are scolding me without saying a word,” the earl said on a sigh. “It was just a kiss, Anna, and I had the impression you rather enjoyed it, too.”

She looked down, while a blush crept up the side of her neck.

“That’s the problem, isn’t it?” he said with sudden, happy insight. “You could accept my apology and treat me with cheerful condescension, but you enjoyedour kiss.”

“My lord,” she said, addressing the hands she fisted in her lap, “can you not accept that were I to encourage your… mischief, I would be courting my own ruin?”

“Ruin?” He said with a snort. “Elise will be enjoying an entire estate for the rest of her days as a token of ruin at my hands—among others—if ruin you believe it to be. I did not take her virginity, either, Mrs. Seaton, and I am not a man who casually discards others.”

She was silent then raised her eyes, a mulish expression on her face.

“I will not seek another position as a function of what has gone between us so far, but you must stop.”

“Stop what, Anna?”

“You should not use my name, my lord,” she said, rising. “I have not given you leave to do so.”

He rose, as well, as if she were a lady deserving of his manners. “May I ask your permission to use your given name, at least when we are private?”

He’d shocked her, he saw with some satisfaction. She’d thought him too autocratic to ask, and he was again reminded of his father’s ways. But she was looking at him now, really looking, and he pressed his advantage.

“I find it impossible to think of you as Mrs. Seaton. In this house, there is no other who treats me as you do, Anna. You are kind but honest, and sympathetic without being patronizing. You are the closest thing I have here to an ally, and I would ask this small boon of you.”

He watched as she closed her eyes and waged some internal struggle, but in the anguish on her face, he suspected victory in this skirmish was to be his. She’d grant him his request, precisely because he had made it a request, putting a small measure of power exclusively into her hands.

She nodded assent but looked miserable over it.

“And you,” he said, letting concern—not guilt, surely—show in his gaze, “you must consider me an ally, as well, Anna.”

She speared him with a stormy look. “An ally who would compromise my reputation, knowing without it I am but a pauper or worse.”

“I do not seek to bring you ruin,” he corrected her. “And I would never force my will on you.”

Anna stood, and he thought her eyes were suspiciously bright. “Perhaps, my lord, you just did.”

He stared after her for long moments, wrestling with her final accusation but coming to no tidy answers. He could offer Anna Seaton an option, a choice other than decades of stepping and fetching and serving. He desired her and enjoyed her company out of bed, a peculiar realization though not unwelcome. But his seduction would be complicated by her reticence, her infernal notions of decency.

For now, he could steal some delectable kisses—and perhaps more than kisses—while she found the resolve to refuse him altogether and send him packing.

He was lingering over his lemonade when Val wandered out looking sleepy and rumpled, shirt open at the throat and cuffs turned back.

“Ye gods, it is too hot to sleep.” He reached over and drained the last of his brother’s drink. “You do like it sweet.”

“Helps with my disposition. And as I did indeed have to deal with His Grace this morning, I feel entitled.”

“How bad was he?” Val asked as he sat and crossed his long legs at the ankle.

“Bad enough. Wanted to chat about the scene at Fairly’s but left yelling about grandchildren and disrespect.”

“Sounds about like your usual with him,” Val said as John Footman brought out a second tray, this one bearing something closer to breakfast.

“Mrs. S said to tell you this one is sweetened, my lord.” John set one glass before the earl. “And this one, less so,” he said as he placed the other before Val.

“I think she puts mint in it,” Val said after a long swallow.

“Mrs. Seaton?” the earl asked, sipping at his own drink. “Probably. She delights in all matters domestic.”

“And she did not appear to be delighting in you, when she was out here earlier.”

“Valentine.” The earl stared hard at his brother. “Were you spying on me?”

Val pointed straight up, to where the balcony of his bedroom overlooked the terrace. “I sleep on that balcony most nights,” he explained, “and you were not whispering. I, however, was sleeping and caught the tail end of an interesting exchange.”

The earl had the grace to study his drink at some silent length.

“Well?” He met his younger brother’s eyes, awaiting castigation.

“She is a decent woman, Westhaven, and if you trifle with her, she won’t be decent any longer, ever again. What is a fleeting pleasure for you changes her life irrevocably, and you can never, ever change it back. I am not sure you want that on your appallingly overactive conscience, as much as I applaud your improvement in taste.”

The earl swirled his drink and realized with a sinking feeling Val had gotten his graceful, talented hands on a truth.

“Maybe,” Val went on, “you should just marry the woman, hmm? You get on with her, you respect her, and if you marry her, she becomes a duchess. She could do worse, and it would appease Their Graces.”

“She would not like the duchess part.”

“You could make it worth her while,” Val said, his tone full of studied nonchalance.

“Listen to you. You would encourage me into the arms of a pox-ridden gin whore if it would result in His Grace getting a few grandsons.”

“No, I would not, or you wouldn’t have gotten that little postscript from me regarding Elise’s summer recreation, would you?”

The earl rose and regarded his brother. “You are a pestilential irritant of biblical proportions. If I do not turn out to be an exact replica of His Grace, it will be in part due to your aggravating influence.”

Val was grinning around a mouthful of muffin, but he nonetheless managed to reply intelligibly to his brother’s retreating back. “Love you, too.”

Anna wasn’t fooled. Since their confrontation over the lunch table earlier in the week, the earl had kept a distance, but it was a thoughtful distance. She’d caught him eyeing her as she watered the bouquets in his library, or rising to his feet when she entered a room. It was unnerving, like being stalked by a hungry tiger.

And as the week wore on, the heat became worse, with violent displays of lightning and thunder at night but no cooling rains to bring relief. The entire household was drinking cold tea, lemonade, and cold cider by the gallon, and livery was worn only at the front door. Everybody’s cuffs were turned back, collars were loosened, and petticoats were discarded.

Anna heard the front door slam and knew the earl had returned after a long afternoon in the City, transacting business of some sort. She assembled a tray and waited to hear which door above would slam next. She had to cock her head, because Valentine was playing his pianoforte. The music wasn’t loud, but rather dense with feeling, and not happy feeling at that.

“He misses our brothers,” the earl said from the kitchen doorway. “More than I realized, as, perhaps, do I.”

The music shifted and became dark, despairing, all the more convincingly so for being quiet. This wasn’t the passionate, bewildered grief of first loss; it was the grinding, desolate ache that followed. Anna’s own losses and grief rose up and threatened to swamp her, even as the earl moved into the kitchen and eyed the tray on the counter.

His eyes shifted back up just in time for Anna to be caught wiping a tear from the corner of her eye.

“Come.” He took her hand and led her to the table, sitting her down, passing her his handkerchief, fetching the tray, then taking the place beside her, hip to hip.

They listened for long moments, the cool of the kitchen cocooning them both in the beauty and pain of the music, and then Val’s playing shifted again, still sad but with a piercingly sweet lift of acceptance and peace to it. Death, his music seemed to say, was not the end, not when there was love.

“Your brother is a genius.”

The earl leaned back to rest his shoulder blades along the wall behind them. “A genius who likely only plays like this late at night among whores and strangers. He’s still a little lost with it.” He slipped his fingers through Anna’s and gently closed his hand. “As, I suppose, am I.”

“It has been less than a year?”

“It has. Victor asked that we observe only six months of full mourning, but my mother is still grieving deeply. I should have offered Valentine a bunk months ago.”

“He probably would not have come,” Anna said, turning their hands over to study his brown knuckles. “I think your brother needs a certain amount of solitude.”

“In that, he and I and Devlin are all alike.”

“Devlin is your half brother?” Ducal bastards were apparently an accepted reality, at least in the Windham family.

“He is.” Westhaven nodded, giving her back her hand. “Tea or cider or lemonade?”

“Any will do,” Anna said, noting that Val’s music was lighter now, still tender but sweetly wistful, the grief nowhere evident.

“Lemonade, then.” The earl sugared his, added a spoonful to Anna’s, and set it down before her. “You might as well drink it here with me, and I’ll tell you of my illustrious family.” He sat again, but more than their hips touched this time, as his whole side lay along hers, and Anna felt heat and weariness in his long frame. One by one, the earl described his siblings, both deceased and extant, legitimate and not.

“You speak of each of them with such affection,” Anna said. “It isn’t always so with siblings.”

“If I credit my parents with one thing,” the earl said, running his finger around the rim of his glass, “it is with making our family a real family. They didn’t send us boys off to school until we were fourteen or so, and then just so we could meet our form before we went to university. We were frightfully well educated, too, so there was no feeling inadequate before our peers. We did things all together, though it took a parade of coaches to move us hither and thither, but Dev and Maggie often went with us, particularly in the summer.”

“They are received, then?”

“Everywhere. Her Grace made it obvious that a virile young lord’s premarital indiscretions were not to be censored, and the die was cast. It helps that Devlin is charming, handsome, and independently wealthy, and Maggie is as pretty and well mannered as her sisters.”

“That would tend to encourage a few doors to open.”

“And what of you, Anna Seaton?” The earl cocked his head to regard her. “You have a brother and a sister, and you had a grandpapa. Did you all get along?”

“We did not,” Anna said, rising and taking her glass to the sink. “My parents died when I was young. My brother grew up with a lack of parental supervision, though my grandfather tried to provide guidance. My parents, I’m told, loved each other sincerely. Grandpapa took us into his home immediately when they died, but as my brother is ten years my senior, he was considerably less malleable. There was a lot of shouting.”

“As there is between my father and me.” The earl smiled at her when she sat back down across from him.

“Your mother doesn’t shout at him, does she?”

“No.” The earl looked intrigued with that observation. “She just gets this pained, disappointed look and calls him Percival or Your Grace instead of Percy.”

“My grandfather had that look polished to a shine.” Anna grimaced. “It crushed me the few times I merited it.”

“So you were a good girl, Anna Seaton?” The earl was smiling at her with a particular light in his eyes, one Anna didn’t understand, though it wasn’t especially threatening.

“Headstrong, but yes, I was a good girl.” She rose again, and this time took his glass with her. “And I am.”

“Are you busy Tuesday next?” he asked, rising to lean against the wall, arms crossed over his chest as he watched her rinse out their glasses.

“Not especially,” Anna replied. “We do our big market on Wednesday, which is also half-day for the men.”

“Then can I requisition your time, if it’s decent weather?”

“For?” She eyed him warily, unable to sense his mood.

“I have recently committed into another’s keeping a Windham property known as Monk’s Crossing,” he explained. “My father and I agree each of my sisters ought to be dowered with some modestly profitable, pleasant property, preferably close to London. Having transferred ownership of one, I am looking at procuring another. The girls socialized little this year, due to Victor’s death, but at least two of them have possibilities that might come to something in the next year. I’d like to have their dower properties in presentable condition.”