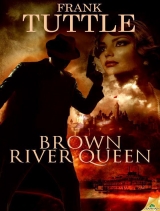

Текст книги "Brown River Queen"

Автор книги: Frank Tuttle

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Frank Tuttle

Brown River Queen

Chapter One

Hammers fell by the hundreds. Lumber wagons rumbled past, either filled to bursting with building materials or freshly emptied and rushing back to the sawmills and the foundries for more timbers and nails. Saws bit deep into kiln-dried pine planks, filling the air with sawdust and the steady scratch-scratch-scratch sound of honest working men earning an honest day’s wage.

Me?

I sat, fundament firmly in the chair I’d placed on the sidewalk. While I sat, I watched a pair of honest working men earn their honest day’s wage by hanging and painting my sturdy new door.

The workmen, a father and son outfit who shared but did not revel in the name Wartlip, were less than appreciative of my audience. For what I was paying them, I decided they could bear the unwelcome scrutiny.

My new door is a beauty. It’s white with a fancy, round glass window worked in at eye level. The window’s thick glass is reinforced with a number of steel bars crossed so that worthies such as myself can peek through them, but objectionable materials like crossbow bolts or the sharp ends of swords will be caught before ruining, for instance, my favorite face. The inside of the oak door conceals a solid iron plate, which means Ogres can spend their days trying to kick their way inside and get nothing for their troubles but twelve hairy, bruised Ogre toes.

Right below the window is a bright brass placard that bears the legend ‘Markhat amp; Hog. Finders for Hire.’

And right below that is the traditional finder’s eye, etched into the brass so that patrons who might have missed the recent rush toward universal literacy can still get close enough to my well-manicured hand to cross my palm with money.

I’m Markhat, founder and senior member of the firm. Miss Gertriss Hog, who bitterly proclaims she does most of the actual work these days, was out doing most of the actual work.

I took another sip of my ice-chilled beer and eyed my new white door critically.

“That top hinge creaks a bit.”

The elder Wartlip muttered something uncomplimentary under his breath.

The Wartlips, like every tradesmen in Rannit these days, had all the work they could get and then some. With half the city lying in various degrees of ruin, anyone who could grasp a hammer suddenly claimed to be a master craftsman and demanded the exorbitant fees to prove it.

I’d waited three days past the appointed date for the Wartlips to show. I wasn’t letting them walk away until my office had a door again, because I knew getting them back to Cambrit Street would be the work of a lifetime.

So they grunted and shimmed and frowned and banged until the door swung without creaking and shut without slamming and opened without a yank or a kick.

I counted out coins. The Wartlips had been adamant about coin. “We ain’t takin’ none of that paper money,” the elder Wartlip insisted, shaking his finger at me for emphasis. “Who’s to say it’ll be any good come tomorrow?”

I hadn’t argued the point. Rannit had nearly fallen to a trio of foreign wand-wavers intent on toppling the Regency and installing some alleged heir to the old Kingdom crown barely a month ago. The invasion had failed, thanks in no small part to my own heroic efforts, but nerves were still shaken and emotions were still raw, and the Regent’s fancy new paper money was viewed by many with open suspicion.

So I counted out five coins, tossed the younger Wartlip a smaller one all his own, and bade the Wartlips a cheery good day.

They and their tools were loaded in their patchwork wagon and headed downtown before I even managed a wave.

Three-leg Cat sidled out of the alley between my place and Mama Hog’s. He gave the door a good hard glare, sniffed it tentatively, and planted his ragged butt down before it. He then set about licking his remaining front paw with a feline air that managed to convey his utter disregard for doors far and wide, even closed ones that stood between him and his food bowl.

“Oh, go on in,” I said, working my new latch. The door swung open without even the faintest ominous creak-I remembered to grab my chair, and Three-leg and I headed indoors for breakfast and meditation, respectively.

I was deeply immersed in profound meditation when the very first knock sounded on my unsullied new door.

Three-leg Cat beat me to it, eager to head out and impose his unique brand of feline terror on the alleys and stoops of Cambrit Street. I took advantage of my new peeping window to see who was calling before I worked the latch.

Outside, wrapped in a mainsail’s worth of black silk against the midday sun, was Evis himself, peering back at me through his tinted spectacles. The halfdead don’t love sunlight the same way I don’t love being bathed in red-hot coals.

“Hurry, please,” said Evis as I fumbled with the lock. “I can’t pay you if I’ve been baked to cinders on your doorstep.”

I managed to swing the door open. Three-leg Cat darted out, heedless of the halfdead at the door. I’ve noticed most animals shy away from Evis, which I believe pains him deeply.

I stood aside and motioned Evis in. He glided into the comfortable shadows of my office, not quite running but not ambling either. I closed the door quickly and resolved to fashion some sort of shade for the window-glass. Even that much light would be a nuisance for Evis and his dead-eyed kin.

“Sorry about the light,” I said as Evis stripped off the top layer of his flowing day suit. “I’ll do something about that before your next visit.”

Evis shrugged it off but kept his dark glasses on. “Thank you. Everything getting back to normal?”

I sat. Evis sat. He kept his hat on and tilted his head so his face remained in deep shadow.

“As normal as normal gets. Business has picked up. Gertriss is out working now. She’ll be sorry she missed you.”

And she would. My junior partner and Evis were spending a lot of time together of late. Had been since their trip up the Brown River on House Avalante’s new-fangled steamboat.

If I was Mama Hog I’d be making pointed comments about all that. Gertriss is Mama’s niece, and Mama is none too thrilled about Gertriss and her recent choice of company. But since I’m not a four-foot-tall soothsayer who claims to be a century and a half old, I don’t stick my nose where it doesn’t belong unless someone is paying me for the effort.

Evis just nodded and put his feet on my desk. His hand moved to his jacket pocket and produced a pair of the expensive cigars he normally keeps in a humidor in his office.

“Uh oh,” I said, opening my desk drawer. I pulled out my notepad and my good pen. “Who’s dead, who’s missing, and how much of the story are you going to leave out?”

Evis kept his lips tightly shut but managed to feign an expression of deep and sincere injury.

“Now is that any way to respond to an offer of a Lowland Sweet?” he asked. “The last time we smoked these you remarked that it was your absolute favorite.”

“And you suddenly remembered that and grabbed a pair and ran all the way down here in the sun just to have a puff. Remarkable.” I put the tip of the pen in my inkwell and then down on the paper.

Evis ignored me and began cutting off the ends with a fancy steel cigar clipper. I found my box of matches and plopped them down on the table.

“So spill it,” I said. “And thanks. I do enjoy these.”

Evis handed me a cigar and struck a match. I let him light it.

It’s not every day a free Lowland Sweet walks through the door.

“Times are changing,” Evis announced after lighting his Lowland and puffing out a perfect smoke ring. “That run at restoring the old Kingdom was the last.”

“So say you.”

“So I do. Care to guess where Prince got the money to rebuild?”

Word from up the Brown is that the storm that nearly wrecked Rannit was a mere ghost of wind compared to the one the Corpsemaster loosed upon our erstwhile enemies in Prince. We’re still getting the odd rooftop or twisted shell of a building, lifted whole from streets in faraway Prince, drifting past on the lazy, muddy water of the Brown. No bodies, though. Not a one.

The Corpsemaster’s wrath is both thorough and lingering.

“No idea. I thought the city fathers in Prince went broke financing their invasion.”

“They did. But our very own Regent graciously made them a loan. At thirty percent interest. Rannit owns Prince now, Markhat. And the Regent won’t be letting them forget that for a very long time.”

I whistled. I hadn’t even heard that rumored.

Evis grinned a brief toothy vampire grin.

“Looks like our military careers are over,” he said. “It’ll be a hundred years before anyone takes another stab at Rannit. Maybe longer. But here we are, still drawing down a Captain’s pay. By the way, any word from the old spook lately?”

Old spook was code for Corpsemaster. Neither Evis nor I had seen her or her black carriage since the dust-up with Prince. Evis had gone so far as to hint that open speculation in some circles indicated the Corpsemaster might have fallen in the fray, or been reduced by the effort to such a state that she’d gone into hiding or hibernation.

I wasn’t quite ready to write her off so quickly, so I just shrugged.

“That’s the second time you’ve mentioned ‘pay,’ you know.” I tried and failed to blow a smoke ring. “Not that I don’t enjoy your company, but what really brought you out for a stroll in the sun?”

“I’m here to hire the famous Captain Markhat on behalf of House Avalante.”

“Didn’t you read the placard? I’m a humble finder, not a Captain. My marching days are done. I’ve taken up pacifism and a strict philosophy of passive non-violence.”

“What’s your philosophy on five hundred crowns-paid in gold-for taking a relaxing dinner cruise down the Brown River to Bel Loit and back? With meals, booze, and as many of these cigars as you can carry, thrown in for free?”

I blew out a ragged column of grey-brown smoke.

“I’m flexible on such matters. But I’m troubled by the offer of five hundred crowns.”

“Make it six hundred, then.”

“I will. If I decide to take it at all. Because that’s a lot of gold, Mr. Prestley. Even Avalante doesn’t just hand the stuff out to see my winning smile. What exactly is worth seven hundred crowns to House Avalante?”

Evis winced. “You are, believe it or not. Look, Markhat. This isn’t just any old party barge outing. The Brown River Queenis a palace with a hull. The guest list reads like Yule at the High House. Ministers. Lords. Ladies. Opera stars. Generals.“

“And? You said it was a pleasure cruise. We won the war and didn’t lose so much as a potato wagon. Handshakes and promotions all around. Why do you need me for eight hundred crowns?”

Evis lifted his hands in surrender.

“Because the Regent himself is coming along for the ride,” he said in a whisper. “Yes. You heard me. The Regent. For every ten who love him there are a thousand who want to scoop out his eyes and boil them and feed them to him.”

“On your boat.”

“On our boat. This is it, Markhat. It’s the culmination of thirty years of negotiations and diplomacy and bribery. House Avalante is a single step away from taking its place at the right hand of the most powerful man in the world. He’ll have his bodyguards. He’ll have his staff. He’ll have his spies and his informants and his eyes and his ears, and that’s just fine with us. But Markhat, we want the man kept safe. We want trouble kept off the Queen. We want a nice quiet cruise from here to Bel Loit and back, and the House figures if anyone can spot trouble coming, it’s you.”

“When you look at things that way, nine hundred crowns is really quite a bargain.”

“Nine hundred crowns it is.” Evis blew another smoke ring and then sailed a second one through it. “And one more thing. Bring the missus. She eats, drinks, stays for free, courtesy of Avalante. Is that a deal?”

“An even thousand crowns for watching rich folks drink. I think you just bought yourself a finder, Mr. Prestley.”

“Surely you have a pair of those awful domestic beers hidden away in your icebox,” said Evis. “I believe we have a toast to make.”

I hurried to the back, knocked damp sawdust off the bottles, and together Evis and I toasted my regrettable return to honest work.

Evis stuck around and drank beer and we talked dates and times, which I dutifully scribbled onto my notepad. He wrapped himself in black silk and darted back out into the sun maybe an hour later, leaving me to my thoughts.

A thousand gold crowns in good solid gold coin. All for a week of work that, on the surface, seemed to involve nothing more perilous than lounging around a floating casino while maintaining an aloof air of menace.

A thousand crowns, though. That’s a lot of money, even in Rannit’s booming post-War economy. A fellow could live quite well on a fraction of that.

Which meant someone high up at Avalante considered the threat of violence against the Regent quite real. Evis didn’t seem to agree. But he hadn’t blinked when I’d upped the ante, either, which meant his bosses had instructed him that money was no object.

“An even thousand crowns,” I said aloud. Darla would be thrilled. We could put a fancy slate roof on our new place on Middling Lane. Hell, we could tear the house down to the last timber and build it back again with twice as many rooms and still have money left over.

If, that is, a fellow lived long enough to collect his shiny gold coins.

I pushed the thought aside, gathered up the empty bottles, and eventually followed Evis out into the bright and bustling light of day.

Chapter Two

I made the block, wary of Ogres and their carts and their general disregard for pedestrian safety every step of the way.

The Arwheat brothers were up on their roof, screaming at each other between bouts of furious hammering. Old Mr. Bull was out on his stoop, muttering to himself, sweeping the same two-by-two step he’d been sweeping since sunrise. I wished him good morning as I passed and was rewarded with a cackle and a brief toothless grin.

Blind Mr. Waters stood in the open door of his bathhouse, squinting up at a sun and a sky he’d never once seen. I knew he was checking on the weather. A bright warm day like today would bring more customers in, requiring him to burn more wood to heat more bathwater.

“Good day to ye, Markhat,” he said as I approached. “Gonna be a right nice day, by the feel of it.”

He held up his right hand, letting the sunlight play through his fingers.

“Looks that way. Good for business.”

The old man nodded, all smiles. “That it is. I ken you’re bound elsewhere, though, is that right?”

“Afraid so, Mr. Waters. I’ll be back soon, though. Miss that brand of soap you carry.”

“Well, I’ll have a hot bath ready when ye are, finder. Take care now.”

“You too.”

And he was gone, closing his door behind him.

I walked on, waving now and then, speaking now and then. I may not live on Cambrit anymore, but a part of me will always call these leaning old timber-frames and none-too-square doors home.

There was one door in particular at which I needed to knock. I’d been dreading the task for days, and even there in the cheery sunshine I nearly just kept walking toward the tidy little single-story cottage with the white picket fence and the bright yellow door that Darla and I bought a few weeks ago.

But in the end, I turned and marched up to Mama’s door and was just about to knock when Mama herself called out from inside.

“I see you standin’ there, boy. Ain’t no need to knock, it ain’t locked.”

“Is that an invitation, Mama?”

Boots scraped floor, and the door swung open.

“Well, it weren’t writ on fancy parchment and delivered with no box of fancy chocolates, but I reckon it was an invite all the same,” she said. “Now are ye comin’ inside or not?”

I took off my hat and ducked under Mama’s doorframe and followed her into the shadows. Mama’s card-and-potion shop is never quite the same from visit to visit. On previous trips, I’d seen shelves filled with jars containing dried birds. I’ve seen neat rows of dead bats, each wearing a tiny mask, nailed in ranks to the walls. Once she even had the place covered with fine nets, inside which a thousand crickets crawled and crept and sang.

So I was prepared for anything-except, perhaps, what I saw.

Mama’s tiny front room was immaculate. The shelves of dried birds were gone, revealing plain wood walls suspiciously bare of cobwebs and charms. A few tasteful paintings hung here and there. Candles in sconces filled the room with a golden, soothing light. The floors were swept and mopped and uncluttered. The black iron cauldron, which had been bubbling with something potently malodorous since the day I’d first set foot on Cambrit, was gone, leaving only a barely visible scorch mark on the floor behind.

“You aimin’ to catch flies with that open mouth of yours, boy?”

“Mama. What happened in here?”

There was a small oak table set in a corner. It sported white lace doilies and a simple red fireflower in a plain crystal vase. Two chairs were pushed neatly beneath the table. Mama pulled out a chair, sat, and motioned for me to do the same.

“The times is changin’, boy. And I’m changin’ with them. Folks is less appreciative of all that old-timey backwoods mumbo-jumbo these days. ‘Specially well-to-do folks.”

The candles on the wall were arranged so that half of Mama Hog’s face was kept in shadow. She leaned forward and I could only see her in silhouette, her wild shock of hair lending a faint corona of light to her form.

“Watch this, boy.”

She closed her eyes and began to whisper, raising her hands beside her face as she spoke.

A light formed at the center of the table, right above the fireflower’s blood-red petals. It was only a spark at first, but it flickered and expanded and intensified, rising and growing, first as bright as a candle and then brighter still.

“Speak,” croaked Mama, opening her eyes.

The light flared. Within it appeared a skull.

A child’s skull, pitiful and small and very, very familiar.

I cussed.

The skull clacked its teeth and issued a faint giggle and vanished. The light that held it flickered and went out as well.

Mama clenched her jaw and crossed her stubby arms over her chest.

“Buttercup, honey, come out,” I said.

More giggling came from above and with it the telltale sound of bare little banshee feet scampering away on the rooftop.

“Mama.”

“Don’t you Mama me, boy.” She waved a finger in my face. “Look here. My niece left the family trade and took to finding. I ain’t got no other suitable kin. And I ain’t getting any younger. What’s the harm in usin’ that banshee a bit if’n it keeps a roof over our heads and soup in our pots? Ain’t neither free nor cheap, and you knows it.”

“You taught Buttercup that trick?”

“She’s always playin’ with that skull anyways, boy. You tried to take it away from her a half dozen times. So have I. But I reckon there ain’t no denying her that thing, and why not gain some good from it?”

We’d rescued Buttercup from an ancient crypt a little over a year ago, and had been hiding her in plain sight by passing her off as Gertriss’s stunted daughter ever since. Mama sticks a pair of obviously fake wings to her back and claims Buttercup is a rare tame forest sprite. The neighbors snicker and nod and wink knowingly at each other, which is exactly the reaction we’d hoped for.

The skull is a more recent and disturbing addition to our little family. The sorcerer who held it expressed a desire to see me dead-I’d declined to participate, and in the fracas, the sorcerer had fallen. I grabbed the skull on my way out, not wanting to leave behind any potentially vengeful witnesses to our little disagreement.

We’d still been trying to decide how to dispose of the skull when Buttercup found it. The tiny banshee may be a thousand years old, but she’s still childlike in some ways, and finding the wand-waver’s talisman filled her with glee. She cuddled it and carried it and whispered nonsense to it constantly. Hiding the skull did no good. We’d never found a place that could conceal it against Buttercup’s sharp little banshee eyes.

Mama even brought in her friend Granny Knot, who claims she speaks to the dead. Granny pronounced the skull haunted by the ghost of an innocent, bound to the bone by a wand-waver’s dark spell, a spell she dared not attempt to unravel. What powers the skull might command, she could not or would not say.

Not that it mattered. Buttercup took the skull everywhere, and on those rare instances she wasn’t holding it, she hid it in places only a sure-footed banshee could reach.

Mama let the ghost of a grin slip. She’d won and she knew it, and I realized she’d been planning this little spook show for days if not weeks.

I sighed. I’d come to try and make peace with Mama, and if I hadn’t expected some stunt like this from her I had only myself to blame.

“Fine. Mama. I didn’t come here to argue with you. You haven’t been coming around lately. When you do see me, you don’t talk. I think we both know why.”

Mama crossed her arms again.

“I’m sure I ain’t got no idea at all what you’re talking about, boy.”

“I’m sure you do. Darla and I got married and you weren’t invited.”

“I reckon it’s your business who you invites to your nuptials, boy. Ain’t no concern of mine.”

I took a deep breath. “We didn’t plan to get married that day, Mama. I’ve tried to explain that. We were just there to keep Darla’s friend safe.”

Mama pulled in air and puffed up. The effect was more toad-like than imposing, but I got the message.

“I thought the world was ending, Mama. The sky went dark. We saw flashes. Heard what I thought was cannon fire. Everyone in Rannit was sure we were dead. You’ve heard the stories. You know I’m telling you the truth.”

“Well, it weren’t no cannons and it weren’t no army and it weren’t no end of the world now, was it?”

I shook my head. “No. It was just Evis and his steamboat full of fireworks. But we didn’t know that. I thought we were about to die. It just…happened.”

Mama snorted.

“Mama, I swear. I didn’t mean to slight you. Darla didn’t mean to slight you.”

“I was planning on deliverin’ a blessing to you both on your wedding day,” said Mama. “Been brewing up a charm for it for a year. A solid year, boy. Put a lot of work into that there charm, I did.”

“I know you did. And we both appreciate that.” I stood. Mama didn’t look up. “We miss you, Mama. I miss you. I’m sorry things happened the way they did. Wars have a way of changing plans whether we want them changed or not. You know that.”

“Then you went and bought a fancy house and moved,” said Mama as my hand closed on her latch. “Without so much as a fare-thee-well.”

“You wouldn’t open your door. Don’t pretend you didn’t hear me knock.”

I got no reply.

“Things have changed, for both of us,” I said, not turning. “Gertriss is living in my old place. I’m married and newly with house. You’ve hidden your birds and bought a broom. But think about this, Mama. We’re still the same people. We can still be as much a part of each other’s lives as we ever were. But that won’t happen if you don’t open the door when somebody knocks.”

Mama didn’t reply. I didn’t wait.

Stubborn as a mule is my old friend Mama Hog.

I left her to her tasteful paintings and fresh-scrubbed floors and headed north, toward home.

The Missus and I have a standing lunch date, breakable only in cases of extreme emergency. She hoofs it toward home from the dress shop, I make my way from the office, and we meet up at the corner of River and Fane before strolling the last three blocks home.

I reached the corner first and killed a quarter of an hour picking out a yellow peony for my lapel and a red fireflower for Darla. Then I decided to ply my detective skills by slipping down the alley by Sylvester’s Hat Emporium and sneaking up behind my betrothed, who was hurrying down Fane with a decided spring in her step and a brown paper parcel in her arms.

I made it within two strides of her when she slowed suddenly and held the package out beside her.

“For heaven’s sake, take this. It’s heavy.”

I took it, and it was.

Darla turned and grinned. “It’s your shoes. I know the sound of your footsteps, my dear, and I can pick them out of a crowd, even a noisy lunchtime crowd.”

“From now on, I’m going barefoot.” I moved the parcel around and drew her in for a kiss, which is no mean feat when neither party stops walking. We made it brief and managed to avoid any collisions. “How is my favorite wife today?”

“Famished. Someone interrupted my breakfast.”

I feigned surprise. “What mannerless ape might that have been? And what’s in the box? More lavish gifts for your new husband?”

She laughed. “Mostly it’s for the kitchen. I found a silverware pattern I liked. Fireflowers and vines.”

“My favorite.”

My beloved grinned. “You’d be content eating with that old knife you keep in your boot.”

“As long as I’m eating.”

“I got you a new hat, too. You’ll love it. Solid black with a dark grey band.” She turned and adjusted the hat I was wearing. “Elegant with just a touch of roguishness.”

I nodded. “That’s me. Elephant with a touch of robbery. But you aren’t fooling anyone, dearest. Confess. You’re in cahoots with my junior partner, aren’t you?”

We stopped to let a nanny and her pair of shrieking infants pass.

The quizzical expression Darla turned toward me was flawless, right down to the tilt of her head and the barely-raised eyebrows.

“In cahoots how?”

I laid my finger on the hatbox’s ornate stamping. “A new black hat. From Carfax. I’m no hat maker, Darla dear, but I know how they rank, and this is the top of the pile.”

“You need a new hat.”

“For our cruise on Evis’s new boat. Since we’ll be rubbing well-dressed elbows with the upper crusts of Rannit’s worthies.”

“Will it help if I flutter my eyelashes and pretend I’ve never heard of Evis?”

“Nope. When did Gertriss tell you?”

“Yesterday. I got myself an evening gown. Black as a crow’s feather. Slit up the side, up to here.” She indicated a spot high up on her right hip.

“You’ll cause a riot.”

She laughed. “Well, if I do, you’re being paid to quell it. Speaking of being paid, how much did you manage to drag out of the poor pale soul?”

“A thousand crowns. In gold.”

She clutched my arm and danced a step.

“A thousand?”

I nodded. “Easy. Without that arm, my suit won’t hang straight. Yes. We’re rich, my dear. Almost rich enough to buy hats from Carfax and gowns from-”

“Eloise’s.”

“Eloise’s, then. So, what’s for lunch? Caviar and hundred-year-old brandy?”

“Sandwiches. Ham. Two slices, since we’re rich.”

I kissed her cheek. “See how quickly decadence takes over? Next we’ll be hiring servants to fan our brows and sleeping on pillows stuffed with money.”

We stopped on the corner while a blue-capped Watchman waved a pair of lumber wagons through the intersection. Darla said something but it was lost in the rumble of wagon wheels and the clip-clop of heavy hooves.

A dozen other pedestrians took up positions beside or behind us while the wagons thundered past.

I was still trying to puzzle out what Darla might have said when a slightly-built young woman dressed all in black tapped me on my left shoulder, smiled at me, and plunged a long sharp knife directly toward my favorite kidney.

I dropped my heavy parcel in the vicinity of her toes and slapped the blade away. Her dainty hand darted under mine, reversed, and bore in on my gut. She never lost her smile.

I half-turned and let her put a rip in my jacket and stepped back. She tried to follow and nearly tripped over Darla’s fireflower-embossed silverware and my good new hat.

It was only then that I heard the shrill and rising banshee’s scream.

The smiling woman with the knife heard it too. Buttercup’s volume is in no way limited by her diminutive stature. Her inhuman howl rose up and up, higher and higher, reaching for a crescendo no human lungs would ever approach, much less match.

The woman hesitated.

I had it in mind to rush her. Grab her knife hand, take a cut if need be, but knock her off her feet and put a knee in her gut and hold her knife hand down until someone could grab the blade.

Instead, Darla, my newlywed wife, simply grabbed the woman by her hair and threw her into the street.

One brief shriek and it was over. The driver of the wagon that ran my would-be murderess down never slowed and certainly didn’t halt.

I turned in a quick circle as my Army knife made its way into my hand. People were shouting and pointing. Some turned away in horror. Others crowded closer to the curb for a better look at the ruined body in the street. No one approached us with mayhem in mind or appeared to slink guiltily away into the crowd.

Buttercup’s hair-raising banshee cry faded quickly. I scanned the nearby rooftops, caught a brief glimpse of a tiny, wild-haired figure scampering away.

Darla pressed herself close.

“Are you wounded?”

“No. You?”

“No.” I felt Darla shiver. Watch whistles blew up and down the street. The Watchman directing traffic came stomping our way.

“What do I say?”

“Crazy woman pulled a knife on me. I pushed her away. She fell into the street.”

“What if someone saw?”

“They’ll get half a dozen different stories anyway. I pushed. She fell.”

“What about Buttercup?”

“I didn’t hear a thing. Did you?”

She shivered again. “That woman. Did you know her?”

“No. Never met her. You?”

Darla shook her head. I saw various eyes cast wholly innocent glances down at our parcel so I snatched it up before it sprouted shoes and ambled away.

“She meant to kill you. Right here on the street.”

“Maybe she couldn’t abide black hats.”

Watchmen stormed into the street, whistles blowing, arms raised against traffic. Blood was pooling and spreading around the crumpled body on the cobblestones. I looked but couldn’t see the knife.

A pair of Watchmen shouldered their way through the crowd. I recognized their faces about the time they recognized mine.

“Well, ain’t this a surprise,” said one. He spat on the sidewalk in open defiance of the Regent’s new ordinance against gratuitous expectoration on public thoroughfares. “Markhat next to a body.”

“I reckon you didn’t have nothin’ to do with this, either,” said the other.

“I wish I could say I was just a bystander,” I said. “But today’s your lucky day because I pushed that woman right in front of a beer wagon.”