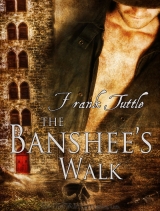

Текст книги "The Banshee's walk"

Автор книги: Frank Tuttle

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

I whistled. “Did father Elt take it hard?”

Evis shrugged. “You’d have to ask him that, Markhat. That’s all I know.”

I sighed, turned my attention back to my cigar and Evis’s brandy.

“That’s some strange country, Markhat,” noted Evis, after a while. “Lots of stories about Wardmoor.”

“Every house is haunted, every shaded lane infested with ghouls,” I agreed. “But don’t worry, I’ll sleep with the sheets pulled up way over my head.”

Evis chuckled. “Just a lot nonsense, those stories. People probably say the same about the Heights.”

I shrugged. People actually said a lot worse, and Evis knew it, but it wasn’t worth pointing out.

“Still, that reminds me, Markhat. There’s something I’ve been meaning to give you, ever since you made the acquaintance of Encorla Hisvin. I’ll be back in a moment, help yourself to another glass.”

Evis rose and padded silently out of the room. I poured, sniffed and drank, alone in a dim chamber deep in a house full of vampires and oddly and completely at ease.

I heard a door click, and Evis was back, a narrow wooden case in his hands.

“Mind you don’t wave this around at the Watch,” he said, handing me the case. “It’s not legal, in the strictest sense, unless you’re a city employee.”

The catch wasn’t locked, so I opened it.

Inside was a sword. A shortsword, about the length of my forearm, with a double-edged silver blade that gleamed with the promise of ready mayhem and a dark wood grip already stained here and there with something that was not applesauce.

“It’s ensorcelled,” said Evis. “Blows struck against reanimated corpses will be particularly efficacious.”

I took it gently from the case. The edges glowed a faint ghostly silver in the candlelight.

Just perfect when dealing with someone named the Corpsemaster, I thought. I wondered briefly if it was also intended for use against the halfdead.

“The spellwork will also be potent against halfdead,” said Evis, very quietly. “It’s the same one we use on our crossbow bolts. Though of course I hope you will use it carefully in that instance.”

I put the sword back in its velvet-lined case and closed it firmly shut.

“I’m always careful with big butter knives,” I said. “And thanks.”

Evis sat. “Don’t thank me,” he replied, grinning. “I have no idea where you got that, never seen it before, anyway I prefer a crossbow myself.” He produced a deck of cards from somewhere in his desk, shuffled them with an expert’s ease and let his dirty white eyes meet mine.

“Surely you have time for a few hands,” he said. “Luck might be with you, tonight.”

I laughed. “Luck lost my address years ago.” I am a lousy card player, and Evis knows it, which is why we never play for real money. “But who knows. Deal, and we’ll see if she’s found me tonight.”

Evis shuffled, and I cut. By the end of the night I was down another four hundred and fifty crowns.

It seems Luck gets lost as easily as I do, in Rannit, these days.

Chapter Five

I’m never late for a date with Darla. She’d be more likely to forgive dirt under my fingernails or Evis’s brandy on my breath than a lack of punctuality.

So I was at her door, with a cab no less, before the Big Bell clanged out seven. We were dining by seven thirty, back at her tiny walk-up by Curfew, and if you want to know anything more than that you’ll have to ask Darla, and good luck.

My Avalante pin on my lapel, I walked home well after midnight. Evis’s magic sword hung beneath my jacket, the tip of it shining every now and then in the moonlight. Darla had frowned and turned away at the sight of it.

“Every sword needs a name,” I said aloud, as I walked. I heard boots scrape somewhere behind me, heard a furtive whisper.

I yanked out the sword, held it high, let it glitter. Boots and whispers withdrew. Rolling Curfew-breaking drunks is one thing, I suppose, but tackling a gleaming sword is something else entirely.

“I dub thee Toadsticker,” I said. “Slayer of miscreants, opener of packages, occasional carver of baked turkeys. Let all men hear, and know mild caution.”

I swear the steel flickered.

I slipped Toadsticker back under my belt. The reason the Army never bothered with hexed weapons was their legendary lack of reliability. It was too easy to turn a hideously expensive magical dingus into a mundane lump of metal by turning it north and sneezing, or by unknowingly performing some other random act that unlatched the hex. Even the mighty wand-wavers occasionally found themselves betrayed by their own fickle handiworks. Like the time old Hooler’s famous iron staff melted right in the face of a Troll charge. They said later the wizard had spilled salt on it while eating supper. A pinch of salt goes astray, and a city falls. Hurrah for modern sorcery.

But you never know when a good sharp length of steel will come in handy, as I’d just demonstrated. I patted Toadsticker’s hilt and hurried home.

Three Leg Cat got me up way before I meant to rise. I groaned and threw pillows, but Three Leg merely shouldered them airily aside and insisted I serve him breakfast.

I was up and shaved and bathed and packed before Mama and Gertriss darkened my door.

“Morning, ladies,” I said, motioning them inside. Mama held a basket that smelled of hot biscuits, and Gertriss carried a big pot of coffee.

Mama merely grunted as she shuffled inside. Gertriss was all smiles, and dressed in the blouse and pants she’d worn home yesterday. She’d also dabbed something fragrant behind her ears, and was making sure I caught a whiff of it by leaning close and fussing with breakfast.

They do learn fast.

“Did you sleep well, Mr. Markhat?” she asked.

“I did indeed,” I answered, rifling through Mama’s basket and selecting a huge biscuit stuffed with thick slabs of ham. “You?”

Gertriss nodded while Mama glared. I grinned and sat.

“You seem a bit quiet this morning, Mama,” I managed, between mouthfuls. I winked at Gertriss, and she perched on my desk and took dainty bites. Mama stood and huffed and refused to sit in my chair. “Run out of bats for the cauldron?”

“You know damned well why I ain’t happy, boy,” she grumbled, with a sideways glance at Gertriss. “Weren’t no need for such things.”

I swallowed and lifted a finger. “That’s where you’re wrong, Mama. You want Gertriss to learn finding, she’s got to look the part. No one is going to open up to a swineherd, much less hire one for finding, and you know it.” I wiped my chin. “That’s how us city folk dress. You don’t have to like it, but if she’s going to work for me that’s what she’ll wear, and that’s final.”

Mama made snuffling noise that might have been grudging assent or a sign of early pneumonia and sat.

I tried not to let too much triumph creep into my tone.

“All packed, Miss?” I asked. “I figure we’ll be there two days, maybe three.”

“All packed, Mr. Markhat,” said Gertriss. She made no effort to conceal the glee in her voice, and I felt a brief stab of sympathy for Mama, who appeared to be learning that young-uns plucked from the country and given a taste of city life might be harder to keep in wholesome, modest burlap than she’d ever dreamed. “Are we leaving soon?”

“As soon as we’ve finished eating and I’ve laid out a few things I learned yesterday.” I launched into a retelling of my gallery visit and the interrupted strangling at the Hemp house and my talk with Evis. Mama lost most of her huff and forgot to pretend she wasn’t listening.

“And that’s all I know right now,” I said, draining the last of my coffee. Gertriss was nodding, taking it all in, and Mama was trying to choke down a hunk of ham so she could speak.

“People just told you, all that?” Gertriss asked. “You didn’t even ask them much, sounds like.”

I nodded. “The trick is just to get them talking, most of the time. You come up to a stranger and start hammering them with questions, usually what you’ll get is silence or a blow to the head. Best thing to do is draw them out. Let them decide to show off by telling you something they think you don’t know.”

Mama guffawed. “Same as with card-readin’,” she said. “Half the time, the real trouble is getting ’em to shut up long enough to say anything yourself.”

Gertriss tilted her head in question. “Is that what we’ll do at House Werewilk?”

“That’s part of it,” I said. “We’ll go, we’ll listen. We won’t start pushing until and if we get the lay of the land and haven’t heard anything suggestive in the first day or so. But I’ll handle most of the talking, this time out. I mainly want you to be another set of ears, another set of eyes.”

“She can do more’n that, boy,” said Mama. “She’s a Hog in more than name. She’s got the Sight, all right, and don’t you forget it.”

Gertriss rolled her eyes. She stopped herself when she realized she was doing it, and Mama didn’t see, but I did.

I let it lie, though. Provoking more of Mama’s familial wrath wasn’t what I had in mind for the start of my day.

So I just nodded sagely. “Noted, Mama,” I said. The light through my door was good and strong, and I had a belly full of ham, and as much as I hate working even I have to admit that’s a good place to start.

“So what about you, Mama?” I asked. “Got any mystical warnings for us, before we head out? Surely a place called the Banshee’s Walk rates an eldritch utterance or two.”

Mama snorted. “Boy,” she said, “don’t think I don’t know what goes on in that thick head of yours. I know you pretends you don’t believe a word I say-but I also know he listens,” she added, with a nod at Gertriss. “’Cause he knows my cards can see what others can’t, sometimes.”

I rose and stretched and yawned. “So spill it, Mama. We need to get moving. Wardmoor is a long way, and part of it on foot.”

“I seen a sword, boy,” snapped Mama. “Ain’t no ordinary sword, neither. Got magic all around it.”

“Have you ever seen me carry a sword, Mama?” I asked.

“I ain’t,” said Mama. “But I reckon you’re carryin’ one now. It’s in your rucksack, ain’t it? I can see it clear from here.”

I frowned. I hadn’t mentioned Toadsticker, wasn’t going to. Sometimes the best weapon is the hidden one.

Maybe Mama saw me with it coming home the night before. Or maybe not. “Keep going,” I said. Mama saw my look and shrugged and dropped it.

“I seen secrets,” she said. “Secrets, and men screaming. Army men. I seen the sky fill with smoke. Fire and death, boy. Lots of it. All around.”

Gertriss looked at me, questioning. I lifted my hand for quiet.

“The Army is nowhere near Wardmoor,” I said. “You know that.”

“I’m tellin’ you what I seen, boy, not what I know,” snapped Mama. “And I seen Army men and fire and death. Might be what’s done happened. Might be what’s to come. Ain’t for me to say.”

Gertriss was getting pale. “All right, Mama,” I said. “Fires and mayhem. How original. Anything else?”

Mama stabbed a stubby finger at me. “I heard wailing, boy,” she said. “Wailing. Like I ain’t never heard before. It was long and loud and, boy, it meant somebody was goin’ to die.” She lowered her hand and sighed. “Just make sure it ain’t goin’ to be you, boy. And make sure it ain’t goin’ to be my niece, neither. You got that?”

“I got it,” I said. “No dying by me or Gertriss, at least not without your permission.”

Mama rose and snatched up her empty basket. “You remember who you are, young Miss,” Mama said to Gertriss, with a glare that would have withered ironwood. Gertriss met it evenly and even managed a smile in return.

“I will, Mama,” she said. “Please don’t worry.”

Mama grunted and caught me in her famous Hog hex-stare.

“You mind you keep that there sword close to hand, boy,” she said.

My yawn wasn’t intentional. But Mama took it as such and whirled and stomped out, cussing and wheezing.

Gertriss wiped crumbs off my desk and stood up. “Is it true?” she asked. “Do you have a sword in there?” She pointed with a nod toward my rucksack in the corner.

“Got a horse and a trebuchet too,” I replied. “I’d bring the catapult, but I like to travel light.”

Gertriss grinned. “So anytime you answer a question with a joke, that’s probably a yes,” she said.

“Sure it is,” I agreed. I stood and heaved my old Army rucksack over my shoulder. “Where’s the rest of your luggage?” I asked. “We should get going.”

“Just inside the door at Mama’s. I’ll fetch it and meet you outside.” She was honest to angels excited about going to work. I shook my head at such a marvel, wondered how long it would last.

She darted away, and I walked out into the light.

It took us two cabs to get to the south end, through neighborhoods that changed quickly from moderately inhabitable row houses to buck-roofed slums and finally to the stink and noise and even worse stink of the cattle yards and slaughterhouses that buttressed the remaining Old Wall on the south.

Even Gertriss, who’d spent her life doing whatever it is country folk do with swine in their swine-yards, held one of my handkerchiefs tight over her nose and mouth and pulled herself as far away from the windows as the cab allowed.

“Not much further,” I said, over the din of frightened cattle and furious drovers. “Then it’s sweet country air and wholesome country sunshine all the way to Wardmoor.”

She nodded, her eyes dubious.

“There are more than six hundred thousand people in Rannit,” I said. “All of them hungry, all of them demanding leather shoes and leather belts and leather coats. This is the only way to keep them fed and hold their pants up.”

She may have grinned behind the handkerchief. I shrugged and leaned back until we rounded the last row of stinking slaughter-barns, and I caught first sight of the Old Wall’s gap-toothed bulk over the rooftops.

“Nearly there,” I said. I shuffled in my seat, ready to get out, even if it meant a long hike. I hoped Gertriss’s new leather boots were a good fit, because blisters or no we were heading to Wardmoor. She was too heavy to carry and it was too far to turn back.

She must have seen me regarding her boots. “I brought my old ones just in case,” she said, her words muffled by the handkerchief. “You won’t have to carry me, Mr. Markhat.”

I lifted an eyebrow. I hadn’t said a word aloud.

Maybe the Hog women do share the gift. That thought sent shivers down my spine.

If Gertriss saw, she had the good grace not to show it.

I hadn’t been south of the city since I was kid. All I remembered from that trip was the cool shade cast by the Old Wall, the lush mosses and huge ferns that covered the shaded parts of it, and the way the noise and stink from the city stopped right as the scent of wet stones and moist soil and green growing things began.

Back then, the cattle roads were well east of where Gertriss and I stood after leaving the cab. Back then, the road I’d taken had been a well maintained if narrow affair made of smooth, carefully set flagstones that wound between arching old pines. Tidy little stone bridges spanned clean, burbling creeks. I’d spent the whole trip fully expecting to see Elves cavorting in the sun-dappled wood at any moment.

My, how things had changed.

The cabbie had laughed when I’d asked him how far he was willing to go. Now I saw why.

The road, or more precisely the wide, flat old pavers that made up the road, was gone. Hauled away by industrious country folk during the War, I surmised, when the Watch was gone fighting and the locals decided their houses and barns needed a new stone or two.

Gone also were the quaint moss-covered stone bridges. Ramshackle post and beam affairs stood in their places, showing profound signs of neglect and weathering.

The clear burbling creeks were foul, muddy rushes, polluted and defiled by the cattle roads, which were now in plain sight and raising a stink even though the wind was blowing toward them.

I regretted not hiring a pair of horses for a week. Gertriss might have brought old boots, but I hadn’t, and we both stood a good chance of turning an ankle on the treacherous, muddy trail ahead.

“Lady Werewilk came through this?” asked Gertriss, incredulous.

“She had a horse and a butler, I imagine,” I said. “Anyway, we don’t have to walk the whole way. She said she’d have a wagon waiting for us up where the road hasn’t been quarried.”

“How far is that?”

“Not sure,” I replied. “Only one way to find out.”

But Gertriss wasn’t listening to me or looking at me anymore. “What’s that?” she asked, taking a step off the trail toward a big swaying pine tree.

I followed her eyes.

The pine had sprouted feathers. Black feathers, crow’s feathers, three of them arranged in a neat triangle right about eye level.

Gertriss touched the ends of them just as something streaked past her shoulder, close enough to ruffle a few strands of her hair.

I was maybe three long strides away. She saw me coming and put up her hands and that’s all she had time to do before I hit her midways and took her down. We rolled, and she snarled and clawed. Despite my weight and experience the only way I got her to be still was by pinning her shoulders and head with my rucksack.

“That was a crossbow bolt,” I said. “Shut up and be still.”

She growled something that didn’t sound much like assent but at least she quit trying to knee me in the groin.

I rolled off her, kept low and kept my rucksack in front of me, and peeped around the big old pine long enough to scan the woods before I pulled my fool head back. I’d seen nothing but trees and scrub, heard nothing but wind and the far-off lowing of cattle, but I knew at least one crossbow-wielding Markhat-hater was lurking somewhere near.

Gertriss scooted closer, biting her lip. I felt blood running down my face, shrugged. “Hush,” I said. “You didn’t know.”

“How many?” she whispered.

“I figure two,” I whispered back. One to reload. One to fire. If they were smart they had at least two crossbows, probably sturdy, quiet army-surplus Stissons.

“What do we do now?” asked Gertriss. She was eyeing my rucksack. It dawned on me that they’d wanted her dead first so she wouldn’t scream when I went down.

I shook my head. “Crossbows trump swords,” I said. “So we wait.”

Gertriss frowned. “Wait for what?”

I heard a tromping in the woods. They were on the move. Hoping to flush us out, flank us, just walk up and bury a pair of black-bodied oak bolts right in our chests.

“Keep your head down low,” I said. “Sidestep every third step. Move fast, be quiet, and don’t stop, not for anything.”

Gertriss went wide-eyed. “But-”

“Just do it.” I fumbled in my rucksack, found Toadsticker and yanked it out in a shower of fresh socks and at least one clean pair of underpants.

I stood, pulled Gertriss to her feet and gave her a shove.

Then I took a deep breath and stepped out of cover.

A couple of things happened then, more or less at the same time. First, a muddy, wild-eyed bull calf came trotting out of the trees on the other side of the old road and sauntered right toward me, bound, I suppose, for anywhere but the cattle-paths and the stink of the slaughterhouses and the city.

Next, from the ruined road that lead south toward Wardmoor, a pair of skinny, cloak-clad teenagers trotted up, jaws agape, their pimpled expressions those of confusion giving quickly way to fear.

Finally, and much to my relief, dogs started barking. Out of sight, but close and loud and getting closer and louder. I knew the Watch uses dogs outside the old walls, and I knew my crossbow-fancier knew that too.

The kids stopped, eyed my sword warily. The bull calf snorted at me and without slowing, ambled past, passing so close I could have patted his muddy head had I been so inclined. I suppose bleeding man, indifferent cow and upraised sword made quite a scene, because the youths exchanged looks and took a step back before speaking.

Neither held a crossbow. Neither would have known what to do with a crossbow had they held it.

“We’re looking for a Mr. Markhat,” said the taller of the two. He had long greasy hair and his boots didn’t match. “We’re supposed to meet him and take him to Wardmoor.”

“We don’t have any money,” said the other kid, quickly. “And we didn’t see nothing, either.”

I listened. Wind and trees and barking dogs. No telltale whisking of bolts through pine needles, no clunk and throw of a Stisson. But I did hear the rattle of a wagon, just around the bend, and a man urging on a horse and another man yelling something as he laughed.

“Gertriss,” I said.

“I’m here,” she replied. I didn’t think she’d taken more than four steps despite my shove and my warning. She had a big stick in one hand and what appeared to be one of Mama’s well-worn kitchen knives in the other.

“Come on out,” I said. “Let’s get moving. It’s bad business to keep the client waiting.”

“So you’re Mr. Markhat?” asked the tall kid. He didn’t try to hide a frown. “We made it over the old Bar bridge after all, got further than we thought. What happened to you?”

Gertriss stepped out into the road, her hands suddenly empty, pine needles in her hair, dirt on both the knees of her good new britches.

“Nothing,” I said. A fat drop of blood formed at the tip of my nose, and I wondered just how deep and long my new scratches were. “The cow made lewd remarks about my apprentice. We had to have words. How far to House Werewilk from here?”

The wagon rolled into view. Two men rode the wagon, one driving, one stretched out in the back with his hat covering his face. By now I was sure that my new friend with the crossbow and the grudge was halfway to the cattle-road if not already across it. Three barking jumping mutt-dogs followed, nipping at the wagon wheels and yelping at each other and even though they were not and would never be huge somber-eyed Watch dogs, I could have hugged them all.

“Not far,” said the greasy-haired kid, who was already eyeing Gertriss with the kind of leer she’d teach him to regret if she caught him in reach of those finely sharpened claws of hers. “You and the lady can ride.”

I hefted my rucksack, and only then did I discover the crossbow bolt lodged deep within it. I’d later find it had penetrated two boot soles and a book before stopping, as well as my best white shirt and a wool sock embroidered by Darla with my initials.

The kid saw and went pale. I shrugged. Let them think I spend every day casually picking crossbow bolts out of everything from my laundry to my oatmeal. If I needed to shake in fear, I’d do so later, in the privacy of my own locked room.

Gertriss came to stand close to me and wiped pine needles and loam off her knees. “They’re gone?” she whispered.

I nodded. “For now.”

I could tell by her look she was having second, third, and possibly fourth thoughts about life as a highly paid finder. But in the end, she picked up her bag and made for the wagon, giving the leering kid a good hard country glare as she marched.

I followed, and we got ponies and dogs and wagons turned around then headed down the ruined road toward the Banshee’s Walk.