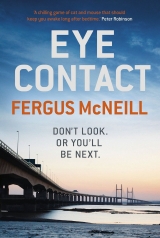

Текст книги "Eye Contact"

Автор книги: Fergus McNeill

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

3

Wednesday, 9 May

He had prepared for it as he would for any other appointment. An entry in his work calendar read Alan Peterson, 9 a.m., Bristol, and the rest of the day was blocked out. The meeting was to discuss a potential lead for what could be a lucrative software contract – he had the brochures and sales sheets in his bag – but a week after landing the Merentha deal, nobody at the office was particularly concerned about how he spent his time.

Which was just as well, Naysmith thought, as there was no Alan Peterson.

Kim was still asleep as he dressed. She looked so innocent, her dark hair tousled from the night before. He gently pulled the duvet up to cover her exposed shoulder and quietly closed the bedroom door behind him.

Time to go to work.

It was a bright, cold morning and he shivered as he carefully hung his jacket in the back of the car to save it from creasing on the journey. He turned on the radio just as the 6 a.m. news started, and listened for the traffic report as he drove out of the slumbering village and made for the main road. Golden sunlight dappled the lane through the overhanging trees, and he found the A36 still quiet enough for him to put his foot down and enjoy the drive. Everything boded well for a productive day.

He made excellent time as far as Bath, then started to run into some early-morning commuter traffic, but he was still in Bristol well before 8 a.m. Threading his way through the city centre as quickly as possible, it wasn’t long before he was driving up the hill into Clifton.

It fascinated him to think about his quarry. Where was she at this moment? What was she doing? Perhaps getting ready for work, maybe already on her way. Certainly she had no understanding of her significance, her part in the game. He wondered how far away she was from him, and imagined the distance closing . . .

There were a couple of empty spaces in the station car park. Getting out of the car, he stretched, then grabbed his jacket and hurried up the tarmac slope, past the station entrance on Whiteladies Road. Moments later, he was settled at a table in Starbucks that commanded a good view of the door, savouring his first coffee of the day, and recalling her image in his mind.

Early thirties, average height, slim figure, straight, mousy hair.

He checked his watch, then sent Kim a short text explaining that his meeting had been delayed, before settling himself into his chair.

From experience, he knew that the key to waiting lay in pacing himself. He had never been a particularly patient man, but he had learned – it was part of the game, like everything else. At first he’d struggled with boredom, frustration and all the other unwanted feelings that crept in to fill the vacuum of inactivity. He’d been too eager to progress and it had almost been his undoing in the early days.

Not now though. Now he knew how to sit so that his body was without tension. He knew how to slow his thoughts and allow his mind the freedom to wander, without ever losing sight of the target.

He had a newspaper in front of him – the Telegraph, which he’d picked up from the counter – but today that was just for show. It was something to put on the table in front of him, a prop he could fiddle with from time to time. It was what people would see when they looked at him – just an ordinary person reading the paper. And yet his eyes, though never too eager, kept glancing back at the door.

He didn’t react when she came in. Her mousy hair was tied back and she was wearing a dark green coat and black boots, but it was definitely her. She looked a little hurried – it was almost nine – but there were only two people in the queue at the counter and she was soon ordering her coffee. Naysmith finished his drink as she collected hers and calmly followed her out onto the street.

She walked with a quick, determined stride as she made her way up the hill, but it wasn’t difficult to stay with her. He allowed her to lead him along the row of shops and through the tempting aroma of fresh bread that drifted from the bakery. He was just a few paces behind her as she crossed the road by the church, but he let the distance between them open up again as they drew nearer to the park. She was some twenty yards ahead of him when she turned off at a terrace of Georgian town houses and hurried up a set of stone steps to a tall, blue door. There she halted to fumble with her handbag, then seemed to think better of it and buzzed the intercom.

Naysmith watched as the door opened and she let herself inside. He was close enough to hear the buzzer click off as he strolled along the pavement, glancing at a small glass plaque by the doorway as he passed: Goldmund & Hopkins Interior Design.

He continued on to the top of the street, then paused and thought for a moment. It was just after nine. There was little reason to wait around for her lunch hour – as long as he was back before five.

The Internet Café, like so many others he had visited, was a seedy place. A bank of computers sat on trestle tables facing the wall, each with its designated number and a plastic chair. They were all vacant save one, where a studious-looking Indian youth was quietly touch-typing to a distant friend. A sign, printed on sheets of A4 paper taped together, advertised web access for £5 per hour, £5 minimum.

Naysmith approached the swarthy man behind the cash desk and wordlessly held out a five-pound note. The man roused himself from his magazine and took the money, placing it quickly into a small cash tin. He then leaned over to his own terminal, tapped a couple of keys and pointed towards the trestle tables.

‘Number four,’ he rasped, then cleared his throat. ‘Any drinks? Tea? Coffee?’

Naysmith looked at the stack of white polystyrene cups and the jar of instant granules. A sheet of paper on the wall behind it read Hot Drinx – £1. He shook his head and silently declined the offer.

Sitting at screen number 4, he brought up a web browser and typed ‘goldmund hopkins interior’ into Google. When he hit Search, a page of entries appeared, but he didn’t need to look beyond the top listing:

Homepage – Goldmund & Hopkins Interior Design Ltd.

He followed the link to their website and was greeted by an impressive page displaying stylish, modern spaces filled with glass and light, but his eye was immediately drawn to the ‘Who We Are’ tab at the top of the screen. Clicking it, he found a section listing the principal members of staff, each with a small photo.

And there she was. Staring out at him from the web page, that same unmistakable face he’d watched in the coffee shop earlier that day, the same face he’d seen in the park a week ago.

Beside the smiling picture, he read her name – Vicky Sutherland.

Naysmith leaned back in his chair and gazed thoughtfully at the screen. He didn’t usually know their names until afterwards.

At ten past five, the blue door opened and Vicky Sutherland appeared, briefly checking her bag before hurrying down the steps to the pavement. She turned onto Whiteladies Road and set off down the hill, buttoning her dark green coat as she walked. On the other side of the street, Naysmith matched her pace.

He’d spent an uplifting afternoon browsing among the dusty shelves of the second-hand bookshop he’d seen the week before. The proprietor, a small man with a shock of white hair and a threadbare grey cardigan, seemed content to sit and read until closing time, and Naysmith had enjoyed searching through the stacks of unwanted hardbacks. In the end, he’d settled on a slim volume of short stories by Somerset Maugham that he remembered reading years ago.

He didn’t look over too often, just enough to make sure he wasn’t getting ahead of that dark green coat. She walked quite quickly, as though she was eager to be away from the office, eager to be home. He wondered where her home was, and what it would be like.

They came to a pedestrian crossing just as the traffic lights were changing to red, halting the long line of cars. Naysmith was about to cross the road when he saw her change direction, stepping off the pavement to come over to his side. He slowed and turned away, pretending to study a shop window. In his mind, he visualised her walking across the road; he counted the steps and the seconds, not turning his head until he was sure she had passed.

The back of her green coat was just a few yards in front of him as they approached the station entrance. It would be easy to lose sight of someone here, but he was careful to stay close and allowed himself a little smile of satisfaction when he saw her turn abruptly off the main road and hurry down the tarmac slope. It seemed they had a train to catch.

A covered footbridge was the only access to the far platform and Naysmith paused, waiting until she was all the way across, before walking onto it and looking out on the station below. There she was, making her way down the long ramp that led to the curved platform, already lined with a number of early-evening commuters.

He checked his wallet for cash – he knew better than to risk using a credit card on a journey like this – when the rattle of an arriving train made him look up.

Mustn’t lose her now.

He hurried across the bridge and down the ramp towards the platform as the other passengers were boarding. It was a short train – only two small coaches – and he just had time to read the destination Severn Beach before leaping aboard through the last open doors. She was sitting with her back to him, at the opposite end of the carriage, so he slid quietly into a seat near the door and calmed his breathing as the train began to move. He gazed out of the window as Clifton Down station slipped away and they crept into the darkness of a long tunnel.

The guard appeared through the connecting door from the other carriage and began to make his way along the narrow aisle, checking tickets. In the fluorescent gloom, Naysmith frowned. He didn’t know which station she was going to. Taking out his wallet, he fished out a ten-pound note and held it ready for the approaching guard. He remembered the destination he’d read as he ran along the platform.

‘Return to Severn Beach, please.’

He could always get off sooner if she was going to an earlier stop.

The guard took his money, tapped a few buttons on a shoulder-slung machine, and printed out two tickets. After counting out the correct change, he walked back towards the other carriage, swaying slightly as the train emerged from the tunnel, daylight bursting in through the windows.

Naysmith blinked and looked out at the bright green foliage whipping by as they joined the river winding its way along the tree-lined Avon Gorge. When they slowed for the first station, he positioned himself so that he could see the back of her head between the seats but she made no move to get up. He settled back into his corner and stared out at the expressionless faces of the people on the platform, then closed his eyes. It had been a long day.

He found himself thinking of all those other faces, still so clear in his memory, each one a challenge, each one a reward. He understood the game now, knew why he played it, what it had given him. Casting his mind back, it was difficult to remember how he’d felt before it all began. He was different now. The game had changed him, altering something deep inside so that he couldn’t empathise with his former self. But there was no regret in that.

He felt the train begin to move. There was a change in tone as they rumbled over a bridge and he opened his eyes again. To the left, the Avon was broader, its sloping banks silted with grey mud. He wondered how far they had to go.

Nobody got off at the next station, but as the train pulled into Avonmouth most of the passengers began to get to their feet and collect their bags. From his vantage point, Naysmith watched intently, but she stayed in her seat, gazing out at the sheltered platform, its back wall decorated by a huge children’s mural.

The doors closed and they began to move once more, clattering slowly over a level crossing and following the single track as it curved steeply round to the right. The train passed in the shadow of an imposing old flour mill that towered like a derelict monument above the other industrial buildings lining the side of the track. There were no more houses now, but vast wind turbines could be glimpsed in the distance, along with cranes and mountainous piles of coal.

‘Any passengers for St Andrews Road?’ the guard called from the connecting door. ‘Request stop only, St Andrews Road.’

A request stop? Naysmith craned his head to peer between the seats. He hoped she wasn’t getting off here. Any station that operated by request didn’t sound as though it saw many passengers, and it would complicate things if he was the only other person to alight there.

He peered between the seats again but she sat still and quiet as the train coasted through a bleak area of warehouses and railway sidings. They rolled through the deserted station without stopping. Sinister-looking chimney towers belched pale fumes into the sky, but eventually even the industrial buildings became less frequent, and Naysmith felt slightly surprised as he realised he was gazing out at one of the Severn Bridges and, across the dark water, the Welsh coastline. Where did this girl live?

And then he felt the train slowing. The remaining passengers began to move, gathering their bags and getting to their feet as the guard called, ‘Severn Beach. Last stop.’

She was standing by the doors at the far end of the carriage, staring out of the window with the unseeing eyes of a tired commuter. Naysmith waited until the doors opened, letting her disembark before he got to his feet and followed.

A chill breeze greeted him as he stepped off the train and he thought he could smell the sea, a faint tang of salt on the air. Severn Beach station was little more than a single long platform between two tracks, one side almost lost in a tangle of overgrown weeds. He walked slowly by the solitary metal shelter and passed the corroded buffers that marked the end of the track, the idling hum of the train dwindling behind him. Ahead, he saw her walking down to the road and turning left. He quickened his pace a little. The platform opened out onto a quiet residential street – old and new houses huddled close to the pavement – a bleak little village on the edge of nowhere.

He turned left and walked along thoughtfully, some fifty yards behind her. It felt like somewhere that old people would come to – a quaint little tea room on one side of the street, bungalows with immaculate gardens, Neighbourhood Watch signs in windows. Ahead, he could see a steep tarmac slope that climbed to what looked like a seaside promenade, but his attention was on the figure in the dark green coat as she followed the road round to the left and disappeared from view.

When he reached the end of the road, he caught sight of her again, but elected to walk up the slope rather than follow her along the pavement. He quickly climbed the few steps up onto the top of the sea wall, and was suddenly buffeted by the wind. Before him, the vast grey expanse of the Severn rippled out towards the horizon, the bridge stretching away into the distance on his right. He turned away from it, pulling his jacket close around him against the cold as he walked along the promenade, his eyes following the figure on the street below as she made her way along the line of waterfront houses and turned down a small cul-de-sac. He watched as she unlocked her front door and went inside. It was a nice house – small, like most modern houses, but with its own driveway and a little patch of lawn. Smiling to himself, Naysmith walked on and followed the path down onto the beach.

The train back to Clifton Down was almost empty. He hadn’t realised how dark it was getting until he stepped aboard, the harsh interior lighting making it almost impossible to see anything outside. His eyelids were suddenly heavy, and he yawned before settling back into the seat. There was still a long drive ahead of him, but it had been a rewarding day.

He’d walked past her house on his way back to the station. There was a light on upstairs, and the hallway was illuminated, but otherwise the place was in darkness. He’d noted the small car on the driveway, the cheerful lace curtains, the plaster animals arranged on the doorstep . . .

. . . but nothing to indicate she lived with a man – good.

He had been about to move on when he’d noticed a pair of muddy women’s running shoes, neatly placed on the mat in the small front porch. And that had given him the beginnings of an idea.

He’d done enough for one day though. Satisfied, he pulled the Somerset Maugham book from his jacket pocket, and began leafing through the familiar pages as the train rumbled out of the station.

4

Friday, 25 May

Naysmith stared down into Kim’s deep brown eyes, enjoying the way she lowered her gaze demurely. Those long lashes looked dark against her pale skin. He carefully swept an errant curl of hair away from her face onto the pillow, then placed a gentle kiss on her forehead.

‘Come on,’ he grinned, rolling off her onto his back and looking up at the ceiling, ‘you’ll be late.’

‘I would have been ready hours ago if you hadn’t been here,’ she smiled, sitting up and tentatively lowering her small, bare feet onto the polished wooden floor.

‘Maybe, but you’re glad I decided to work at home this morning.’

He stretched his arms out across the bed as she looked back over her shoulder at him.

‘Of course I am.’ She stuck her tongue out playfully, then squealed as he tried to grab her. Jumping up, she put her hands on her hips and adopted a mock-serious expression. ‘Not again. I’ll be late.’

He watched her scamper naked into the bathroom, then sank back into the pillows for a moment. His hand found the watch on the bedside table and he held it up, squinting as sunlight from the window glinted on the bezel: 12.49 p.m. It was time to get ready.

Naysmith put the suitcase down on the tarmac and closed the car boot.

‘Say hi to your sister for me.’ He smiled.

‘I will.’ She checked her bag, then turned to him. ‘Are you sure you don’t mind me going?’

‘It was my idea,’ he reminded her.

‘You’ll be all right on your own, won’t you?’

‘For goodness’ sake . . .’

He rolled his eyes, and she flinched. Very slightly, but he saw it – one of those nervous little tells that drew him to her, like a flame to a moth.

‘It’s only till Sunday,’ he said in a gentler voice. ‘Now go on, before you miss your train.’

She extended the handle from the case, then turned and stood on tiptoes to kiss him.

‘Call me tonight?’

‘I’ll call you tonight.’

He waved to her, watching her bump the wheeled suitcase through the doors and disappear into the station building. Then, sighing to himself, he got back into the car and leaned forward to rest his head on the steering wheel for a moment. He closed his eyes and drew a deep breath.

Time to focus.

He filled the car with petrol on his way out of Salisbury. Every forecourt had CCTV – that was unavoidable – but he deliberately paid in cash. Credit cards left permanent records that were simple to collate. Patterns and coincidences stood out too easily, and at this stage in the game he always disciplined himself to leave as little trace as possible. Tomorrow, he would refill the car somewhere else.

He didn’t take the turning for the village but drove on along the main road for a mile and a half before pulling off onto a narrow lane that led along the edge of a small copse. Leaving the car in the overgrown gateway to an empty field, he walked the short distance to the trees, pausing now and again to admire the rolling Wiltshire landscape, and to ensure there was nobody else around. Pushing on into the wood, he left the faint path and picked his way up a gentle incline, stopping when he came to a heap of rubble covered in ivy. He looked around, then stood very still, holding his breath and listening intently for a moment, but there was no sound other than the gentle rustle of the leaves above. Satisfied that he was alone, he crouched down and carefully pulled the undergrowth away from a small section of collapsed brick wall. Leaning forward, he reached into the gap underneath, searching with his fingers. It was further back than he remembered, but it was there, and he felt a tiny spark of excitement as he gained a grip on the plastic. Carefully, he drew out the long, flat parcel, wrapped in layer upon layer of black refuse sacks. He stood up, brushing the dirt and insects from it, and pushed the ivy back into place with his foot. Resisting the temptation to open it, he took his prize and started back down the slope towards the car.

It was almost five o’clock when he got home. Getting out of the car, he went straight into the garage, closing the door quietly behind him before turning on the light. It was a cramped space, cluttered with old packing cases and tools, and he had to step round the two bicycles to reach the cardboard boxes stacked along the back wall. One of them lacked the film of dust that covered the others. Opening it, he drew out two plastic bags and checked the contents.

Dark hooded top, anorak, jogging bottoms, black trainers, plain T-shirt, socks, gloves, cheap wristwatch . . .

To these he added a bottle of thin bleach, a roll of refuse sacks and a travel pack of hand-wipes. Every eventuality prepared for. Everything bought from the local supermarket, paid for with cash – anonymous items that could have come from any town.

He transferred the bags into a single refuse sack, which he carried out to the car, then went into the house.

A little before midnight, he called Kim, smiling as she struggled to hear him over the background noise of the bar she was in.

‘What was that?’

‘I said, tell your sister I can hear that screeching laugh from here.’

‘Rob, don’t be so mean.’

‘You’re right. She has a lovely screech.’

‘Stop it!’ Kim laughed. ‘So have you had a nice evening? You haven’t been too bored, have you?’

‘I’ve got a bottle of Bombay Sapphire and I’m watching The Godfather DVDs you got me,’ Naysmith lied. ‘I decided I was due a lazy night in.’

‘That’s good,’ Kim shouted. ‘Look, I can hardly hear you. I’ll call you tomorrow, OK?’

‘Not too early.’

‘All right. Miss you.’

‘’Night.’

He stood up and walked into the living room. Pulling the box of The Godfather from the shelf, he took one of the discs and put it into the DVD player, then moved through to the kitchen. Opening the cupboard, he took out the large blue bottle and poured three-quarters of the Bombay Sapphire down the sink.

Details mattered.

The warm water felt good on his skin as he leaned back under the shower nozzle, energising him. It was part of the ritual that he went through every time, helping him to prepare physically and mentally for the challenge. He wrapped a towel around himself and padded through to the bedroom, where he clipped his fingernails short. All jewellery, along with his watch, his wallet and his mobile phone were left neatly on the bedside table – personal items were an unacceptable risk. He needed nothing but his keys and some cash.

Once dry, he dressed himself quickly and went downstairs. After switching on the TV and the sitting-room lights, he slipped quietly out into the cool night air.

The Warminster Road was deserted but he took no chances. He chose a quiet farm track, screened by tall hedges, and drove some distance before pulling over. Stepping out into the darkness, he went round to the back of the car and opened the boot. Carefully undoing the black plastic bags, he unwrapped the flat parcel to reveal a pair of car number plates and a small white envelope.

It had taken him time to source those plates. He’d noted the registrations of several cars the same colour and model as his own, eventually settling on one he saw in Basingstoke. Blank plates and self-adhesive letters were relatively simple to obtain, and after an evening’s work in the garage and some carefully applied grime, he had a pair of passable fakes. They weren’t perfect, but they were enough to give his own vehicle a different identity for all the watchful CCTV cameras – a legitimate identity that would attract no attention, and which had no connection to him if it was ever spotted. Time well spent.

Crouching down, with a torch gripped between his knees, he worked quickly to tape the plates securely over his own, ensuring a perfect fit. Once he was satisfied, he stowed the torch and took the white envelope in his hand, feeling the contents between his fingers before carefully slipping it into his pocket.

Moments later, his car rejoined the main road and he accelerated away, the route now very familiar to him. This would be his fourth visit to Severn Beach – he’d made two preparatory trips in the weeks since he’d tracked her there – and it would be his last.

He cruised past Warminster and drove on into the night, enjoying the long, clear road as it snaked towards him out of the darkness. Bath was asleep, a succession of empty streets and glaring traffic lights, soon left behind as he pressed on towards the orange glow of Bristol on the horizon. There was a little more traffic here, but it was quiet enough as he swept down towards the city centre and round to Hotwells. The Clifton Bridge hung like a strip of fairy lights above the gorge, and he found himself leaning forward to gaze up as he passed beneath it.

Not far now . . .

Avonmouth was a ghost town, and he was suddenly conscious of being alone – conspicuously alone – on the silent roads. This close to his destination, a local police car would present too great a risk. He would have no choice but to postpone and drive on. The thought irked him as he came to the roundabout by the towering old mill and turned off onto the broad, straight length of St Andrews Road. He was watchful now, checking each side turning as it slipped by, glancing up at the mirror to see anyone behind him, but there was nobody else. He was alone.

A little before Severn Beach, there was a turning for a single-track access road that led down towards the water – he’d found it on his second visit and it seemed the ideal place. He drove a short distance along it, then switched off the headlights and looked behind him for other cars.

Nothing.

He waited a few moments, allowing his eyes to grow used to the darkness, then cautiously eased the car forward along the narrow tarmac. It was difficult without lights, especially negotiating the low bridge where the road passed under the railway line. The shore side of the tracks was a dead end, hidden from the main road by the embankment – probably the local lovers’ lane but now, just after 3 a.m., it was empty. He turned the car so that it was facing out, ready to leave, then switched off the engine and got out.

A chill wind whipped along the shoreline, rippling the tall reeds like waves. Naysmith stretched and yawned, savouring the bite of the cold after the soporific warmth of the car journey. The Second Severn Crossing dominated the night horizon, a ribbon of motorway lights cast out across the miles of dark water, its reflection glittering on the river below. He shivered and went back to the car, opening the boot and drawing out the refuse sack containing his new clothes. After one last check to ensure he had everything, he locked the car and set off into the wind, trudging along the swathe of rough grass that divided the railway from the beach.

He made his way on into the darkness until he came to a solitary tree and the large group of bushes gathered about it. Pausing for a moment, he looked around, then carried the plastic sack into the midst of the bushes and laid it carefully on the ground. Beside it, he placed the white envelope – an incongruous pale square in the gloom. Removing the keys and cash from his pocket, he took a new refuse sack and began methodically undressing, placing each item of clothing into the sack. It was cold, but it would be folly to rush – he had to make sure that everything was accounted for. At last, naked, he gathered the top of the sack and twisted it shut, before opening the other bag and taking out his anonymous new clothes.

A few minutes later, shivering but dressed, he pulled his gloves on before pushing the black sack deep into the bushes. Shoving his keys and cash into empty pockets, he stared down at the envelope for a moment, then scooped it up and made his way out onto the beach.

The grass gave way to small stones that crunched underfoot as he drew closer to the shore, an endless strip of shingle and debris that marked the uncertain boundary between the land and the estuary. The first houses were visible now, less than a mile ahead, the outermost arm of the village stretching out towards him.

He walked on as the sky began to brighten, the pre-dawn light giving form to dark, heavy clouds. He hoped it might rain, but not until later. Not until afterwards. Water washed away a multitude of sins.

There was one more thing to attend to. Picking his way along the beach, he began to study the larger stones that lay here and there among the pebbles.

Something round and heavy that would fit well in the hand . . .

He stooped to examine several river-smoothed rocks before he found what he was looking for. It felt right as he picked it up, testing the weight and swinging it experimentally. It also had the beauty of coming from this shoreline – he could drop it anywhere and even if it was discovered, it would only reinforce the idea that the whole thing was opportunistic rather than planned. Nodding to himself, he slipped the stone into one of his large anorak pockets and walked on towards the Severn bridges.

As the ground fell away before him, he came to the start of the sea wall that protected the low-lying houses beyond. He walked along the beach below it, keeping close to shield himself from the worst of the wind, and to stay out of sight. Finding a sheltered spot, he sat down on the stepped concrete at the base of the wall and checked his cheap watch. All he had to do now was wait.