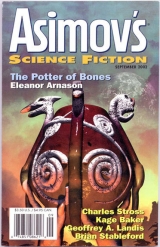

Текст книги "The Potter of Bones"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 4 страниц)

"You see why I have no children," Dapple said, then tilted her head toward the carpenter. "Though my kinswoman here has two sets of twins, because her gift is making props. We don’t tell our relatives that she also acts."

"Not much," said the carpenter.

"And not well," muttered the apprentice sitting next to Haik.

The captain stayed a while longer, chatting with Dapple about his family and her most recent plays. Finally he rose. "I’m too old for these long evenings. In addition, I plan to leave for Ettin at dawn. I assume you’re sending love and respect to my mother."

"Of course," said Dapple.

"And you, young lady." The one eye roved toward her. "If you come this way again, bring pots for Ettin. I’ll speak to my mother about a breeding contract with Tulwar. Believe me, we are allies worth having!"

He left, and Dapple said, "I think he’s imagining a male relative who looks like you, who can spend his nights with an Ettin woman and his days with Ettin Taiin."

"What a lot of hard work!" the carpenter said.

"There are no Tulwar men who look like me."

"What a sadness for Ettin Taiin!" said Dapple.

From Hu Town they went west and south, traveling with a caravan. The actors and merchants rode tsina,which were familiar to Haik, though she had done little riding before this. The carrying beasts were bitalin: great, rough quadrupeds with three sets of horns. One pair spread far to the side; one pair curled forward; and the last pair curled back. The merchants valued the animals as much as tsina,giving them pet names and adorning their horns with brass or iron rings. They seemed marvelous to Haik, moving not quickly, but very steadily, their shaggy bodies swaying with each step. When one was bothered by something–bugs, a scent on the wind, another bital–it would swing its six-horned head and groan. What a sound!

"Have you put bitalinin a play?" she asked Dapple.

"Not yet. What quality would they represent?"

"Reliability," said the merchant riding next to them. "Strength. Endurance. Obstinacy. Good milk."

"I will certainly consider the idea," Dapple replied.

At first the plain was green, the climate rainy. As they traveled south and west, the weather became dry, and the plain turned dun. This was not a brief journey. Haik had time to get used to riding, though the country never became ordinary to her. It was so wide! So empty!

The merchants in the caravan belonged to a single family. Both women and men were along on the journey. Of course the actors camped with the women, while the men–farther out–stood guard. In spite of this protection, Haik was uneasy. The stars overhead were no longer entirely familiar; the darkness around her seemed to go on forever; and caravan campfires seemed tiny. Far out on the plain, wild sulincried. They were more savage than the domestic breeds used for hunting and guarding, Dapple told her. "And uglier, with scales covering half their bodies. Our sulinin the north have only a few small scaly patches."

The sulinin Haik’s country were entirely furry, except in the spring. Then the males lost their chest fur, revealing an area of scaly skin, dark green and glittering. If allowed to, they’d attack one another, each trying to destroy the other’s chest adornment. "Biting the jewels," was the name of this behavior.

Sitting under the vast foreign sky, Haik thought about sulin. They were all varieties of a single animal. Everyone knew this, though it was hard to believe that Tulwar’s mild-tempered, furry creatures were the same as the wild animals Dapple described. Could change go farther? Could an animal with hands become a pesha?And what caused change? Not trickery, as in the play. Dapple, reaching over, distracted her. Instead of evolution, she thought about love.

They reached a town next to a wide sandy river. Low bushy trees grew along the banks. The merchants made camp next to the trees, circling their wagons. Men took the animals to graze, while the women–merchants and actors–went to town.

The streets were packed dirt, the houses adobe with wood doors and beams. (Haik could see these last protruding through the walls.) The people were the same physical type as in Hu, but with grey-brown fur. A few had faint markings–not spots like Dapple, but narrow broken stripes. They dressed as all people did, in tunics or shorts and vests.

Why, thought Haik suddenly, did people come in different hues? Most wild species were a single color, with occasional freaks, usually black or white. Domestic animals came in different colors. It was obvious why: people had bred them according to different ideas of usefulness and beauty. Had people bred themselves to be grey, grey-brown, red, dun and so on? This was possible, though it seemed to Haik that most people were attracted to difference. Witness Ettin Taiin. Witness the response of the Tulwar matrons to her father.

Now to the problems of time and change, she added the problem of difference. Maybe the problem of similarity as well. If animals tended to be the same, why did difference occur? If there was a tendency toward difference, why did it become evident only sometimes? She was as red as her father. Her daughters were dun. At this point, her head began to ache; and she understood the wisdom of her senior relatives. If one began to question anything–shells in rock, the hand in a pesha’s flipper–the questions would proliferate, till they stretched to the horizon in every direction and why, why, whyfilled the sky, like the calls of migrating birds.

"Are you all right?" asked Dapple.

"Thinking," said Haik.

At the center of the town was a square, made of packed dirt. The merchants set up a tent and laid out sample goods: dried fish from Hu, fabric made by northern weavers, boxes carved from rare kinds of wood, jewelry of silver and dark red shell. Last of all, they unfolded an especially fine piece of cloth, put it on the ground and poured out their most precious treasure: a high, white, glittering heap of salt.

Townsfolk gathered: bent matriarchs, robust matrons, slim girls and boys, even a few adult men. All were grey-brown, except the very old, who had turned white.

In general, people looked like their relatives; and everyone knew that family traits existed. Why else select breeding partners with so much care? There must be two tendencies within people, one toward similarity, the other toward difference. The same must also be true of animals. Domestic sulincame in different colors; by breeding, people had brought out variations that must have been in the wild animals, though never visible, except in freaks. She crouched in the shadows at the back of the merchants’ tent, barely noticing the commerce in front of her, thinking difficult thoughts.

Nowadays, geneticists tell us that the variation among people was caused by drift in isolated populations, combined with the tendency of all people to modify and improve anything they can get their hands on. We have bred ourselves like sulinto fit in different environments and to meet different ideas of beauty.

But how could Haik know this much about the history of life? How could she know that wild animals were more varied than she had observed? There are wild sulinin the far northern islands as thick furred and white as the local people. There is a rare, almost extinct kind of wild sulinon the third continent, which is black and entirely scaly, except for a ridge of rust-brown fur along its back. She, having traveled on only one continent, was hypothesizing in the absence of adequate data. In spite of this, she caught a glimpse of how inheritance works.

How likely is this? Could a person like Haik, living in a far-back era, come so near the idea of genes?

Our ancestors were not fools! They were farmers and hunters, who observed animals closely; and they achieved technological advances–the creation through breeding of the plants that feed us and the animals we still use, though no longer exclusively, for work and travel–which we have not yet equaled, except possibly by going into space.

In addition to the usual knowledge about inheritance, Haik had the ideas she’d gained from fossils. Other folk knew that certain plants and animals could be changed by breeding; and that families had traits that could be transmitted, either for good or bad. But most life seemed immutable. Wild animals were the same from generation to generation. So were the plants of forest and plain. The Goddess liked the world to stay put, as far as most people could see. Haik knew otherwise.

Dapple came after her, saying, "We need help in setting up our stage."

That evening, in the long summer twilight, the actors performed the peshacomedy. Dapple had to make a speech beforehand, explaining what a peshawas, since they were far inland now. But the town folk knew about sulin, tli,and penises; and the play went well, as had the trading of the merchants. The next day they continued west.

Haik traveled with Dapple all summer. She learned to make masks by soaking paper in glue, then applying it in layers to a wooden mask frame.

"Nothing we carry is more valuable," said the costume maker, holding a thick white sheet of paper. "Use this with respect! No other material is as light and easy to shape. But the cost, Haik, the cost!"

The bitalincontinued to fascinate her: living animals as unfamiliar as the fossils in her cliffs! Her first mask was a bital. When it was dry, she painted the face tan, the six horns shiny black. The skin inside the flaring nostrils was red, as was the tongue protruding from the open mouth.

Dapple wrote a play about a solid and reliable bitalcow, who lost her milk to a conniving tli. The tliwas outwitted by other animals, friends of the bital. The play ended with Dapple as the cow, dancing among pots of her recovered milk, turned through the ingenuity of the tliinto a new substance: long-lasting, delicious cheese. The play did well in towns of the western plains. By now they were in a region where the ocean was a rumor, only half-believed; but bitalinwere known and loved.

Watching Dapple’s performance, Haik asked herself another question. If there was a hand inside the pesha’s flipper, could there be another hand in the bital’s calloused, two-toed foot? Did every living thing contain another living thing within it, like Dapple in the bitalcostume?

What an idea!

The caravan turned east when a plant called fire-in-autumn turned color. Unknown in Tulwar, it was common on the plain, though Haik had not noticed it till now. At first, there were only a few bright dots like drops of blood fallen on a pale brown carpet. These were enough to make the merchants change direction. Day by day, the color became more evident, spreading in lines. (The plant grew through sending out runners.) Finally, the plain was crisscrossed with scarlet. At times, the caravan traveled through long, broad patches of the plant, tsinaand bitalinbelly-deep in redness, as if they were fording rivers of blood or fire.

When they reached the moist coastal plain, the plant became less common. The vegetation here was mostly a faded silver-brown. Rain fell, sometimes freezing; and they arrived in the merchants’ home town at the start of the first winter storm. Haik saw the rolling ocean through lashes caked with snow. The pleasure of salt water! Of smelling seaweed and fish!

The merchants settled down for winter. The actors took the last ship north to Hu Town, where the innkeeper had bedrooms for them, a fire in the common room and halinready for mulling.

At midwinter, Dapple went to Ettin. Haik stayed by the ocean, tired of foreigners. It had been more than half a year since she’d had clay in her hands or climbed the Tulwar cliffs in search of fossils. Now she learned that love was not enough. She walked the Hu beaches, caked with ice, and looked for shells. Most were similar to ones in Tulwar; but she found a few new kinds, including one she knew as a fossil. Did this mean other creatures–her claw-handed bird, the hammer-headed bug–were still alive somewhere? Maybe. Little was certain.

Dapple returned through a snow storm and settled down to write. The Ettin always gave her ideas. "When I’m in the south, I do comedy, because the people here prefer it. But their lives teach me how to write tragedy; and tragedy is my gift."

Haik’s gift lay in the direction of clay and stone, not language. Her journey south had been interesting and passionate, but now it was time to do something. What? Hu Town had no pottery, and the rocks in the area contained no fossils. In the end, she took some of the precious paper and used it, along with metal wire, to model strange animals. The colors were a problem. She had to imagine them, using what she knew about the birds and bugs and animals of Tulwar. She made the hammer-headed bug red and black. The flower-predator was yellow and held a bright blue fish. The claw-handed bird was green.

"Well, these are certainly different," said Dapple. "Is this what you find in your cliffs?"

"The bones and shells, yes. Sometimes there is a kind of shadow of the animal in the rock. But never any colors."

Dapple picked up a tightly coiled white shell. Purple tentacles spilled out of it; and Haik had given the creature two large, round eyes of yellow glass. The eyes were a guess, derived from a living ocean creature. But Haik had seen the shadow of tentacles in stone. Dapple tilted the shell, till one of the eyes caught sunlight and blazed. Hah! It seemed alive! "Maybe I could write a play about these creatures; and you could make the masks."

Haik hesitated, then said, "I’m going home to Tulwar.–"

"You are?" Dapple set down the glass-eyed animal.

She needed her pottery, Haik explained, and the cliffs full of fossils, as well as time to think about this journey. "You wouldn’t give up acting for love!"

"No," said Dapple. "I plan to spend next summer in the north, doing tragedies. When I’m done, I’ll come to Tulwar for a visit. I want one of your pots and maybe one of these little creatures." She touched the flower-predator. "You see the world like no one else I’ve ever met. Hah! It is full of wonders and strangeness, when looked at by you!"

That night, lying in Dapple’s arms, Haik had a dream. The old woman came to her, dirty-footed, in a ragged tunic. "What have you learned?"

"I don’t know," said Haik.

"Excellent!" said the old woman. "This is the beginning of comprehension. But I’ll warn you again. You may gain nothing, except comprehension and my approval, which is worth little in the towns where people dwell."

"I thought you ruled the world."

"Rule is a large, heavy word," said the old woman. "I made the world and enjoy it, but rule? Does a tree rule the shoots that rise at its base? Matriarchs may rule their families. I don’t claim so much for myself."

When spring came, the company went north. Their ship stopped at Tulwar to let off Haik and take on potted trees. There were so many plants that some had to be stored on deck, lashed down against bad weather. As the ship left, it seemed like a floating grove. Dapple stood among the trees, crown-of-fire mostly, none in bloom. Haik, on the shore, watched till she could no longer see her lover or the ship. Then she walked home to Rakai’s pottery. Everything was as Haik had left it, though covered with dust. She unpacked her strange animals and set them on a table. Then she got a broom and began to sweep.

After a while, her senior relatives arrived. "Did you enjoy your adventures?"

"Yes."

"Are you back to stay?"

"Maybe."

Great-aunts and uncles glanced at one another. Haik kept sweeping.

"It’s good to have you back," said a senior male cousin.

"We need more pots," said an aunt.

Once the house was clean, Haik began potting: simple forms at first, with no decoration except a monochrome glaze. Then she added texture: a cord pattern at the rim, crisscross scratches on the body. The handles were twists of clay, put on carelessly. Sometimes she left her hand print like a shadow. Her glazes, applied in splashes, hid most of what she’d drawn or printed. When her shelves were full of new pots, she went to the cliffs, climbing up steep ravines and walking narrow ledges, a hammer in hand. Erosion had uncovered new fossils: bugs and fish, mostly, though she found one skull that was either a bird or a small land animal. When cleaned, it turned out to be intact and wonderfully delicate. The small teeth, still in the jaw or close to it, were like nothing she had seen. She made a copy in grey-green clay, larger than the original, with all the teeth in place. This became the handle for a large covered pot. The body of the pot was decorated with drawings of birds and animals, all strange. The glaze was thin and colorless and cracked in firing, so it seemed as if a film of ice covered the pot.

"Who will buy that?" asked her relatives. "You can’t put a tree in it, not with that cover."

"My lover Dapple," said Haik in reply. "Or the famous war captain of Ettin."

At midsummer, there was a hot period. The wind off the ocean stopped. People moved when they had to, mouths open, panting. During this time, Haik was troubled with dreams. Most made no sense. A number involved the Goddess. In one, the old woman ate an agala. This was a southern fruit, unknown in Tulwar, which consisted of layers wrapped around a central pit. The outermost layer was red and sweet; each layer going in was paler and more bitter, till one reached the innermost layer, bone-white and tongue-curling. Some people would unfold the fruit as if it were a present in a wrapping and eat only certain layers. Others, like Haik, bit through to the pit, enjoying the combination of sweetness and bitterness. The Goddess did as she did, Haik discovered with interest. Juice squirted out of the old woman’s mouth and ran down her lower face, matting the sparse white hair. There was no more to the dream, just the Goddess eating messily.

In another dream, the old woman was with a female bital. The shaggy beast had two young, both covered with downy yellow fur. "They are twins," the Goddess said. "But not identical. One is larger and stronger, as you can see. That twin will live. The other will die."

"Is this surprising?" asked Haik.

The Goddess looked peeved. "I’m trying to explain how I breed!"

"Through death?" asked Haik.

"Yes." The Goddess caressed the mother animal’s shaggy flank. "And beauty. That’s why your father had a child in Tulwar. He was alive in spite of adversity. He was beautiful. The matrons of Tulwar looked at him and said, ‘We want these qualities for our family.’

"That’s why tame sulinare furry. People have selected for that trait, which wild sulinconsider less important than size, sharp teeth, a crest of stiff hair along the spine, glittering patches of scales on the sides and belly, and a disposition inclined toward violence. Therefore, among wild sulin,these qualities grow more evident and extreme, while tame sulinacquire traits that enable them to live with people. The peshaonce lived on land; the bitalclimbed among branches. In time, all life changes, shaped by beauty and death.

"Of all my creatures, only people have the ability to shape themselves and other kinds of life, using comprehension and judgment. This is the gift I have given you: to know what you are doing and what I do." The old woman touched the smaller bitalcalf. It collapsed. Haik woke.

A disturbing dream, she thought, lying in darkness. The house, as always, smelled of clay, both wet and dry. Small animals, her fellow residents, made quiet noises. She rose and dressed, going to the nearest beach. A slight breeze came off the ocean, barely moving the hot air. Combers rolled gently in, lit by the stars. Haik walked along the beach, water touching her feet now and then. The things she knew came together, interlocking; she achieved what we could call the Theory of Evolution. Hah! The Goddess thought in large ways! What a method to use in shaping life! One could not call it quick or economical, but the Goddess was–it seemed by looking at the world–inclined toward abundance; and there was little evidence that she was in a hurry.

Death made sense; without it change was impossible. Beauty made sense; without it, there couldn’t be improvement or at least variety. Everything was explained, it seemed to Haik: the pesha’s flipper, the claw-handed bird, all the animals she’d found in the Tulwar cliffs. They were not mineral formations. They had lived. Most likely, they lived no longer, except in her mind and art.

She looked at the cloudless sky. So many stars, past all counting! So much time, receding into distance! So much death! And so much beauty!

She noticed at last that she was tired, went home and went to bed. In the morning, after a bad night’s sleep, the Theory of Evolution still seemed good. But there was no one to discuss it with. Her relatives had turned their backs on most of existence after the Drowning. Don’t think badly of them for this. They provided potted beauty to many places; many lineages in many towns praised the Tulwar trees and pots. But their family was small, its future uncertain. They didn’t have the resources to take long journeys or think about large ideas. So Haik made more pots and collected more fossils, saying nothing about her theory, till Dapple arrived late in fall. They made love passionately for several days. Then Dapple looked around at the largely empty town, guarded by dark grey cliffs. "This doesn’t seem like a good place to winter, dear one. Come south with me! Bring pots, and the Ettin will make you very welcome."

"Let me think," said Haik.

"You have ten days at most," Dapple said. "A captain I know is heading south; I asked her to stop in Tulwar, in case your native town was as depressing as I expected."

Haik hit her lover lightly on the shoulder and went off to think.

She went with Dapple, taking pots, a potter’s wheel, and bags of clay. On the trip south–through rolling ocean, rain and snow beating against the ship–Haik told Dapple about evolution.

"Does this mean we started out as bugs?" the actor asked.

"The Goddess told me the process extended to people, though I’ve never found the bones of people in my cliffs."

"I’ve spent much of my life pretending to be one kind of animal or another. Interesting to think that animals may be inside me and in my past!"

On the same trip, Haik said, "My family wants to breed me again. There are too few of us; I’m strong and intelligent and have already had two healthy children."

"They are certainly right in doing this," said Dapple. "Have you picked a father?"

"Not yet. But they’ve told me this must be my last trip for a while."

"Then we’d better make the most of it," Dapple said.

There had been a family argument about the trip; and Haik had gotten permission to go only by saying she would not agree to a mating otherwise. But she didn’t tell Dapple any of this. Family quarrels should be kept in the family.

They spent the winter in Hu. It was mild with little snow. Dapple wrote, and Haik made pots. Toward spring they went to Ettin, taking pots.

Ettin Taiin’s mother was still alive, over a hundred and almost entirely blind with snow-white fur. But still upright, as Taiin pointed out. "I think she’ll go to the crematorium upright and remain upright amid the flames."

He said this in the presence of the old lady, who smiled grimly, revealing that she’d kept almost all her teeth.

The Ettin bought all the pots Haik had, Taiin picking out one with special care. It was small and plain, with flower-predators for handles, a cover and a pure white glaze. "For my mother’s ashes," the captain said quietly. "The day will come, though I dread it and make jokes about it."

Through late winter, Haik sat with the matriarch, who was obviously interested in her. They talked about pottery, their two families and the Theory of Evolution.

"I find it hard to believe we are descended from bugs and fish," Ettin Hattali said. "But your dreams have the sound of truth; and I certainly know that many of my distant ancestors were disgusting people. The Ettin have been improving, due to the wise decisions of my more recent ancestors, especially the women. Maybe if we followed this process far enough back, we’d get to bugs. Though you ought to consider the possibility that the Goddess is playing a joke on you. She does not always speak directly, and she dearly loves a joke."

"I have considered this," said Haik. "I may be a fool or crazy, but the idea seems good. It explains so much that has puzzled me."

Spring came finally. The hills of Ettin turned pale blue and orange. In the valley-fields, bitalinand tsinaproduced calves and foals.

"I have come to a decision," the blind old woman told Haik.

"Yes?"

"I want Ettin to interbreed with your family. To that end, I will send two junior members of my family to Tulwar with you. The lad is more like my son Taiin than any other male in the younger generation. The girl is a fine, intelligent, healthy young woman. If your senior female relatives agree, I want the boy–his name is Galhin–to impregnate you, while a Tulwar male impregnates Sai."

"It may be a wasted journey," said Haik in warning.

"Of course," said the matriarch. "They’re young. They have time to spare. Dapple’s family decided not to breed her, since they have plenty of children; and she is definitely odd. It’s too late now. Her traits have been lost. But yours will not be; and we want the Ettin to have a share in what your line becomes."

"I will let my senior female relatives decide," said Haik.

"Of course you will," said Ettin Hattali.

The lad, as Hattali called him, turned out to be a man of thirty-five, shoulder high to Haik and steel grey. He had two eyes and no limp. Nonetheless, his resemblance to Taiin was remarkable: a fierce, direct man, full of good humor. Haik liked him at once. His half-sister Sai was thirty, a solid woman with grey-brown fur and an excellent, even temperament. No reasonable person could dislike her.

Dapple, laughing, said, "This is Ettin in action! They live to defeat their enemies and interbreed with any family that seems likely to prove useful."

Death and beauty, Haik thought.

The four of them went east together. Haik put her potter’s tools in storage at the Hu Town inn; Dapple took leave of many old friends; and the four found passage on a ship going north.

After much discussion, Haik’s senior relatives agreed to the two matings, impressed by Galhin’s vigor and his sister’s calm solidity, by the rich gifts the Ettin kin had brought, and Haik’s description of the southern family.

Nowadays, with artificial insemination, we don’t have to endure what happened next. But it was made tolerable to Haik by Ettin Galhin’s excellent manners and the good humor with which he handled every embarrassment. He lacked, as he admitted, Taiin’s extreme energy and violence. "But this is not a situation that requires my uncle’s abilities; and he’s really too old for mating; and it would be unkind to take him from Hattali. Who can say how long she will survive? Their love for each other has been a light for the Ettin for years. We can hardly separate them now."

The two foreigners were in Tulwar till fall. Then, both women pregnant, the Ettin departed. Haik returned to her pottery. In late spring, she bore twins, a boy and a girl. The boy died soon after birth, but the girl was large and healthy.

"She took strength from her brother in the womb," said the Tulwar matriarchs. "This happens; and the important child, the female, has survived."

Haik named the girl Ahl. She was dun like her older sisters, but her fur had more of a ruddy tint. In sunlight, her pelt shone red-gold; and her nickname became Gold.

It was two years before Dapple came back, her silver-grey fur beginning to show frost on the broad shoulders and lean upper arms. She admired the baby and the new pots, then gave information. Ettin Sai had produced a daughter, a strong child, obviously intelligent. The Ettin had named the child Haik, in hope that some of Tulwar Haik’s ability would appear in their family. "They are greedy folk," said Dapple. "They want all their own strength, energy, solidity and violence. In addition, they want the beauty you make and are.

"Can you leave your daughter for a while? Come south and sell pots, while I perform my plays. Believe me, people in Hu and Ettin ask about you."

"I can," said Haik.

Gold went to a female cousin. In addition to being lovely, she had a fine disposition, and many were willing to care for her. Haik and Dapple took passage. This time, the voyage was easy, the winds mild and steady, the sky clear except for high, thin clouds called "tangled banners" and "schools of fish."

"What happened to your Theory of Evolution?" Dapple asked.

"Nothing."

"Why?"

"What could be done? Who would have believed me, if I said the world is old beyond comprehension; and many kinds of life have come into existence; and most, as far as I can determine, no longer exist?"

"It does sound unlikely," Dapple admitted.

"And impious."

"Maybe not that. The Goddess has an odd sense of humor, as almost everyone knows."

"I put strange animals on my pots and make them into toys for Gold and other children. But I will not begin an ugly family argument over religion."

You may think that Haik lacked courage. Remember that she lived in an era before modern science. Yes, there were places where scholars gathered, but none in her part of the world. She’d have to travel long distances and learn a new language, then talk to strangers about concepts of time and change unfamiliar to everyone. Her proof was in the cliffs of Tulwar, which she could not take with her. Do you really think those scholars–people devoted to the study of history, mathematics, literature, chemistry, and medicine–would have believed her? Hardly likely! She had children, a dear lover, a craft, and friends. Why should she cast away all of this? For what? A truth no one was likely to see? Better to stay home or travel along the coast. Better to make pots on her own and love with Dapple.