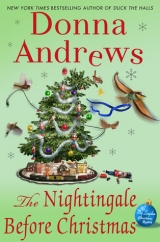

Текст книги "The Nightingale Before Christmas"

Автор книги: Donna Andrews

Жанр:

Иронические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Chapter 18

The woman’s words grew louder, and I could hear Sammy trying to calm her down and hold her back. With no success. She burst into the garage and looked around, puzzled at seeing us there. She was petite, buxom, redheaded, and probably attractive when she wasn’t hysterical. She focused on me and her face contorted with rage.

“Who the hell are you and what are you doing here?” she shrieked, and launched herself at me, fingernails poised to attack. Horace and Sammy both grabbed her and held her back, taking damage in the process.

“Madam!” the chief roared.

The woman stopped struggling and fixed her gaze on him.

“I am Henry Burke, chief of police here in Caerphilly. Ms. Langslow is assisting me in an investigation. You have already opened yourself to charges of assaulting a police officer in the performance of his duties.”

“Two police officers,” Sammy corrected.

The chief favored him with a withering glance.

“Kindly cease this ridiculous behavior and tell me who you are and what you’re doing here,” the chief went on.

“My name is Felicia Granger, and Clay is my … my friend.” She pulled herself up and stood still. Sammy and Horace let go of her, but stood ready in case she backslid.

Granger—she was probably the wife of the man who’d been following me the night before.

“And your purpose in coming here?” the chief asked.

Felicia seemed to wilt.

“We were supposed to see each other last night,” she said. “He never showed up, and never returned my calls, and—did something happen to him?”

“I’m afraid Mr. Spottiswood is dead,” the chief said, very gently.

Felicia uttered a shriek and fell in a small heap on the floor.

The chief and his officers seemed taken aback by the violence of her grief, and I ended up being the one to help her up, lead her back to the living room, plunk her down on the couch, and say “there, there” as she cried on my shoulder.

The chief had the presence of mind to send Sammy for a glass of water and Horace for a box of tissues, and then ordered them to get back to work searching Clay’s house.

After a while, when Felicia’s sobs finally subsided, she sat up, wiped her nose on the back of her hand, and looked over at the chief.

“How did he die?” she asked.

The chief paused, obviously weighing the effect of what he was about to say, before he answered.

“I’m afraid he was shot,” he said.

“Oh, my God!” Felicia turned pale and clapped both hands over her mouth. “He did it! He really did it!”

“Who did it?” The chief sounded irritated. I could tell Felicia was wearing on his nerves. He wasn’t the only one.

“My husband,” she said. “Ex-husband. Well, not quite ex yet, but we’ve been separated for two months. And he hates Clay. He said he’d kill him if he didn’t leave me alone. Lots of times.”

“That would be Mr. Gerald Granger?” the chief asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Jerry’s been threatening to—”

The door flew open, and Jerry himself burst in.

“Aha!” he exclaimed. “Caught you red-handed! I’m going to—what’s going on here?”

“That’s him,” Felicia said, pointing to the new arrival. “That’s Jerry.”

“I have already met Mr. Granger,” the chief said. “Sit down!” he snapped at the newcomer.

Mr. Granger flinched at the chief’s fierce tone and scuttled over to the chair with surprising meekness. The chief scowled at him for a few moments, as if making sure he was planning to stay put. Then he turned back to me.

“Meg,” he said. “Take Mrs. Granger to the garage and ask Sammy and Horace to keep an eye on her. I need to have a few words with Mr. Granger about his violation of the restraining order against him.”

“You’re going to arrest him, aren’t you?” Felicia said, as I pulled her to her feet and started steering her toward the kitchen. “Because he did it.”

“Somebody did the world a favor,” Jerry said. “But it wasn’t me.”

“You bastard!” she shrieked. She tried to launch herself at him, but unlike Sammy and Horace, I had considerable experience dealing with juvenile tantrums. She wasn’t a particularly large woman, so I slung her over my shoulder in a fireman’s carry and hauled her out to the garage, still kicking and shrieking. Sometimes it comes in handy being not only taller than average but, thanks to my blacksmithing work, a lot stronger than most women.

“The chief says keep an eye on her,” I said to Sammy and Horace, who looked alarmed at her return.

“Bitch,” she said to me, but she seemed to have calmed down.

“What happened?” Sammy asked.

“My husband happened.” Felicia grabbed Clay’s recycling bin, turned it upside down to dump the contents on the garage floor, and sat on it, with her elbows on her knees and her head in her hands. “He killed Clay Spottiswood.”

“He’s a suspect,” I said. “How did you and Clay meet, anyway?”

“He decorated our living room.” Felicia shook her head. “You want to know the ironic thing? I didn’t want to hire him in the first place. I actually preferred one of the other designers who gave us a proposal. But Jerry liked Clay’s designs. Said he wanted a masculine look in the living room, not a lot of female frippery.” She chuckled mirthlessly. “Bet now he wishes he’d picked Martha Blaine’s design.”

Interesting. Of course, I’d already figured out that in Caerphilly’s relatively small interior design community, the major players all knew each other, and had done battle over potential clients many times. But given the antagonism I’d already seen between Clay and Martha …

“She tried to poison me against him, you know,” Felicity said.

“Martha?”

“Yes. Tried to tell me all sorts of wild stories about him being a criminal or something. She’s a piece of work. If Jerry wants to hire her to redo the room Clay decorated—well, at least I won’t have to deal with her.”

“So now what happens?” I said aloud. “With you and Jerry.”

“Now that Clay’s dead, you mean?” She shrugged.

“You don’t think you’ll get back together?”

“No.” She shook her head. “Clay wasn’t my true love. Just my exit strategy. I’m not going back to Jerry. I’m tired of him knocking me around.”

But she looked so bleak that I wondered if she’d stick to that. I wouldn’t want to bet against the notion that by next Christmas, she and Jerry would be back together.

Assuming neither one of them turned out to be Clay’s killer.

“So where have you been staying?” I asked. “At the local women’s shelter?”

“I didn’t know we had a local women’s shelter,” she said. “And no, I’ve been staying with a friend in Westlake.”

Westlake was one of the posher local suburbs, the sort of place where people who could afford decorators were apt to live. Her tone implied that people with friends rich enough to live in Westlake had no need of a women’s shelter. I hoped she was right. Though I suspected the women I’d seen last night at the shelter were there out of fear, not economic need.

The chief stuck his head in.

“Mrs. Granger? We’d like you to come down with us to the station.”

“Great,” she said. “What did Jerry tell you?”

“Nothing yet,” he said. “I’d rather talk to both of you down at the station.”

She heaved herself off the recycling bin and headed toward the door. The chief stepped aside to allow room for her to pass. Sammy followed her.

“Horace is going to process those packages,” the chief said. “And then he’ll bring them back to the show house. We’d like to talk to each of the people whose packages were stolen.”

“Okay.” I nodded. “I gather Mr. Granger got out on bail this morning.”

“Yes,” the chief said. “But he won’t be for long. Last month Judge Shiffley granted his wife a protective order against him. He violated that by showing up here. And it’s his third violation, which means a mandatory six-months sentence.”

“And what are the odds Judge Shiffley will let him make bail twice in less then twenty-four hours?” I asked.

“Slim.” The chief smiled slightly. “We’ll also be charging him for everything he got up to last night. Should hold him for a while.”

“Long enough for you to figure out if he killed Clay?” I suggested.

The chief didn’t answer, but his face wore a look of satisfying anticipation, like a cat who had a mouse cornered and was looking forward to playing with it.

“So did you figure out why Mr. Granger was following me last night?” I asked.

The chief frowned.

“I’m afraid that’s partly our fault,” he said. “I had him in for questioning yesterday—Martha Blaine suggested him as one of Mr. Spottiswood’s clients who might have reason to dislike him.”

“That’s the understatement of the year,” I muttered. And I suspected Martha had enjoyed having a chance to get back at the Grangers for choosing Clay over her.

“And while he was down at the station,” the chief went on, “it appears he overheard several of my officers discussing their inability to locate Mrs. Granger for questioning. One of them suggested going over to the show house to ask someone with a connection to the Caerphilly women’s shelter if Mrs. Granger had taken up residence there. Apparently, after spending some time observing the comings and goings at the show house, Mr. Granger decided that you were the connection.”

“Based on what?”

“He was unable to articulate his reasons,” the chief said. “He’d ingested a considerable quantity of alcohol. He was well past the legal limit when we administered the Breathalyzer.”

“I should get back to the house,” I said. I followed the chief back into the living room. Which was empty of feuding Grangers; I could see Sammy escorting Felicia to his cruiser. Another cruiser was pulling away, presumably with another deputy escorting Jerry.

“Now that he’s safely locked up, I’m rather glad Mr. Granger showed up,” I said. “After all, it’s starting to look as if everyone in the house is alibied, and if none of the designers did it—”

Oops. Probably not the smartest thing in the world to let the chief know I’d been poking around behind his back. He was frowning.

“Sorry,” I said. “But we’re all there together all day. The designers talk to each other—and to me. Everyone who has an alibi is thrilled, and wants everyone to know all about it.”

“Mr. Granger is only a suspect at this point,” he said. “And the designers are not all completely alibied. Unless you know differently.”

That sounded like an invitation to share.

“Well,” I said. “Mother was with family, and Martha was serving as designated driver and chief nurse for Violet, who was soused, and the Quilt Ladies were at Caerphilly Assisted Living, and Eustace was with his AA sponsee—”

“Ah,” the chief said. “That explains why he said he’d have to get back to me with his alibi.”

“Oh, dear,” I said. “I hope I wasn’t supposed to keep that part a secret. Don’t tell him I spilled it. And he didn’t tell me the name. And Sarah was neutering cats—”

“Doing what?”

“Neutering cats. Feral cats. With Clarence.”

“I think I could have lived without that image,” he said, shaking his head. “She only told me she was working at the animal shelter.”

“Who does that leave? Oh. Ivy. I don’t know about Ivy.”

“Home alone with a migraine, which doesn’t prove much,” he said. “But it’s possible the snow will alibi her.”

“The snow?” I had a brief image of the chief with his pen poised over his notebook, attempting to interrogate a falling flake.

“One of her neighbors is an avid amateur photographer,” the chief said. “And particularly fond of snowy landscapes without a single footprint in them. Apparently, due to her headache, Ivy did not emerge to shovel until sometime in the afternoon, and the neighbor took a great many pictures of the virginal snow in her front and backyard. Horace is analyzing them, and thinks it likely that she’ll be alibied.”

“Oh, good,” I said. “And did Our Lady—did Linda talk to you about her alibi?”

“Also home alone,” he said.

“Home alone, but online,” I said. “You got my e-mail about that, right? Because while I don’t understand it myself, I gather if she really was online, it might be provable.”

“I’ve already spoken to our department’s computer forensic consultants,” he said.

“And Vermillion was with the Reverend Robyn, at the women’s shelter. The location of which I’m busily trying to forget.”

“I don’t actually know it myself,” the chief said. “I suppose they let you in on the secret because of your gender.”

“They didn’t let me in on the secret,” I said. “Vermillion has absolutely no idea how to be discreet and furtive. She might as well be driving around with a neon sign on her car saying ‘Please don’t follow me! I’m going someplace I don’t want anyone to know about.’”

“I’ll speak to the Reverend Smith,” the chief said, with a smile. “Offer to give her couriers some lessons on defensive driving. I used to be pretty good at it, back in my undercover days in Baltimore. I don’t think I’ve quite forgotten everything I used to know. And I feel I owe them something, after my department inadvertently alerted Mr. Granger to their existence.”

“That would be great,” I said. “But anyway, with so many of the designers alibied, it must be very satisfying to find some fresh, juicy suspects.”

“I’d rather just find the killer,” he said. “But yes, Mrs. Granger and her jealous husband bear looking into. As does the disgruntled client Stanley told me about, the one who was suing Mr. Spottiswood. Meanwhile, there’s another small matter you can help me with.”

“Glad to,” I said.

“That student reporter you mentioned—the one who was visiting the house the day Mr. Spottiswood was killed.”

“And was wandering around for quite a while, taking photos. Yes.”

“I wanted to follow up on your suggestion that I look at her photos. What was her name again?”

“Jessica,” I said. “Sorry—I can’t remember her last name. You can probably find her through the paper.”

“But you’re sure it was Jessica?”

“Yes—why?”

“I dropped by the student paper office today,” he said. “Only one person there holding down the fort, since the college is on Christmas break. But she didn’t remember anyone sending a reporter over to do a story on the show house. And they don’t have a Jessica on staff. She looked through all their files.”

He let me ponder that for a while.

“Maybe Jessica’s trying to wangle a spot on their staff by coming up with a good story,” I suggested at last. “Maybe she’s off writing up her exciting account of the show house where one of the designers was murdered. The paper’s on hiatus until classes start up again, so she’d have no reason to turn it in yet.”

“Maybe.” He didn’t sound as if he found the idea too plausible.

“Damn! I didn’t ask her for any credentials.” I was getting angry now. “I sent a press release over to the student paper, and a week later, someone shows up saying she’s here to write a story. I fell for it.”

“It’s a natural mistake.”

“She played me.”

“So let’s find her. Ask her what she was up to.”

“How?”

“I’ve called the student records office,” he said. “They have photos of all the students in their files. Go down there and they’ll show you all the Jessicas.”

“All the Jessicas? You think they’ll have a lot of them?”

“Did you know that between 1981 and 1997, Jessica was either the number one or number two most popular name in this country? And it hasn’t been out of the top two hundred since 1965.”

I closed my eyes and sighed.

“So yes, there are quite a lot of them. And if none of the Jessicas look familiar, they’re going to let you thumb through the whole student photo file. Women students, anyway.”

“If she’s there, I’ll find her,” I said.

“And meanwhile, in case she’s not there. I’m arranging to bring in a sketch artist,” he said. “So call me as soon as you identify her … or when you’ve looked through all the records.”

So much for having a productive day.

Chapter 19

I drove over to the campus and prowled around until I found a parking space reasonably close to the administration building. If classes had been in session, I might almost as well have walked from Clay’s house, but most of the students were gone now. And the administration building wasn’t all that close to any of the shops and restaurants being overrun by holiday tourists and locals alike.

The student records office was festively decorated with tinsel and evergreens and a small tree in the corner, but I detected no signs of Christmas spirit in the single glum staffer sitting behind the information counter.

“You must be the one here for the Jessicas.” She stood up and walked over to open a little gate and let me behind the counter that separated visitors from staff. “We’ve got all the student photos in a database. Should be online, really, but our IT guys are always too backed up to get to it. I’ve got you set up here at this computer.”

She pointed to a desk toward the back of the room.

“Thanks,” I said. “Please tell me you’re not here right now just to let me in.”

“No,” she said. “My boss insists that we have someone here any day that’s not a federal holiday. I drew short straw this year. I’m Jen, by the way.”

“Meg.”

We shook hands. She showed me how to page through the photos. Then she drifted back to her desk, picked up her coffee mug, and came back to sit on the file cabinet beside me, where she could watch as I paged through the photos.

“Why are you looking for this kid, anyway?” she asked after a while.

“She pretended to be a reporter from the student newspaper,” I said. “But they don’t have a Jessica. And she might have information relevant to a case Chief Burke is working on.”

“The murder,” she said, nodding. “Is she a suspect?”

“No idea. Is this all the Jessicas you’ve got?”

“Guess she was using a fake name. I can show you the rest of the women students. Hang on a sec.”

She leaned over, punched a few keys. Large numbers of men and women students appeared on the screen. Another few keystrokes and the men disappeared.

“Help yourself,” she said.

It took an hour, during which I found out all about the family Christmas revels Jen’s boss was keeping her from enjoying, and her plans to look for a new job after the holidays.

Michael’s mother called me once, right in the middle of my search.

“What’s your family’s gluten situation?”

I looked at the phone in dismay.

“I had no idea we had a gluten situation,” I said finally. “What kind of situation?”

“I meant, are a lot of your family going gluten free, or is it safe to have rolls and a bread-based stuffing?”

“I think it’s safe to have rolls,” I said. “As long as you don’t force anyone to eat them at gunpoint. But I have no idea how many people are avoiding gluten. Maybe a gluten-free stuffing would be best.”

“I’ll do both, then,” she said, and hung up.

“Mother-in-law,” I said to Jen.

“Tell me about it.”

I persevered to the end, from the Abramses and Addisons all the way to the Zooks and Zuckers, but finally I had to admit defeat.

“She’s not here,” I said.

“Could be a townie,” Jen said. “A lot of townies pretend to be students at the college. Especially if they’re trying to get into bars.”

“Yeah, but this one wasn’t trying to get into a bar. She was touring a half-completed decorator show house.”

“Was there anything missing after she left?”

“Good question,” I said. I wasn’t about to mention the gun that might have gone missing.

“You should check carefully,” she said. “We’ve started seeing a lot of it. Crooks in their teens or early twenties. They come here and they just blend in. Everyone looks at them and sees students. If you don’t know them you just figure they’re transfer students, or students in a department whose building is on the other side of campus. It’s not like a neighborhood where people get to know each other and call the police if they see a stranger hanging around.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Unfortunately, there’s not much we can do in hindsight.”

We wished each other a merry Christmas and I left. She seemed sorry to see me go. Clearly her boss’s desire to have someone in the office wasn’t motivated by a heavy workload. I suspected I had been the highlight of an otherwise boring day.

I waited till I was outside again to call the police.

“No dice,” I said. “Jessica was definitely not a student.”

“Blast,” he said. That was usually as close to cursing as the chief went, so I knew he was seriously frustrated.

“I’m heading back to the house,” I said. “Unless you need me to do anything else.”

“Just be careful,” he said.

As soon as I stepped in the door of the show house, Sarah and Violet came running to meet me.

“Did you hear?” Sarah said. “The police found all our packages.”

“Clay did have them after all,” Violet said. “What a horrible man!”

“Martha was livid,” Sarah said. “If he wasn’t already dead, I think she’d probably strangle him over this.”

“And I’d probably help her,” Mother said from the doorway of her room.

I was still taking off my coat when Randall pulled up in a panel truck.

“Got that new mattress for Clay’s room,” he said, as he came in the front door. “Can anyone help me haul it in?”

Eustace said a few words in Spanish to Tomás and Mateo, and they raced out the door.

“And I found some black sheets and a bedspread to replace the damaged ones,” Randall went on, handing me a bag from a well-known discount chain. “Had to send my cousin Mervyn down to Richmond for them.”

“Excellent,” I said, pulling the package of sheets out of the bag.

“These are cotton polyester blend,” Eustace said, in a tone of utter horror.

“Yeah,” Randall said. “That’s what Mervyn could find down in Richmond. Not a hot item in the River City, black sheets.”

“Clay’s were Egyptian cotton with a fifteen hundred thread count,” Eustace said.

“And now they’re locked up in the Caerphilly Police Department’s evidence room,” Randall said. “And even if the chief let us have them back, between the bloodstains and damage from the ax the killer used to wreck the room, they don’t look so pretty.”

“I seem to remember Clay saying he had to special order the sheets from somewhere,” I said. “And they took forever to get here. Even if we knew his source, it’s not as if we have the time to order them all over again.”

“And it’s also not as if the people coming through the house are going to wallow on the sheets,” Randall said. “We’ll probably have a docent in here to make sure no one touches a thing.”

“Well, go ahead,” Eustace said. “Who knows? If you actually put those sorry things on the bed in Clay’s room, he just might rise from the dead to smite you, and save Chief Burke the trouble of solving his murder.”

With that he strode majestically back to his own room.

“Do you really think anyone will notice?” I asked Mother. “Or care?”

“If anyone does, we can tell them it was a deliberate design decision on Clay’s part,” Mother said.

I suspected this was a subtle attempt to sabotage Clay’s posthumous reputation, but I didn’t really care.

Tomás and Mateo appeared at the front door, carrying the mattress. I followed them upstairs and watched as they efficiently put it in place and left, taking the packaging materials with them.

I opened the package of sheets—okay, they weren’t the softest I’d ever felt, but they looked fine. I made the bed, and topped it off with a matching black coverlet.

And someone had responded to my pleas for design assistance and added a few token Christmas decorations. The dresser now held a red bowl filled with gold-painted magnolia leaves, flanked by two red candles in black glass holders. Not my idea of a proper Christmas decoration—it was beautiful but cold and uninviting, and I couldn’t help comparing it to our house, where Mother had achieved beautifully decorated rooms that seemed to welcome friends, toys, dogs, carols, cups of hot chocolate, and Christmas cookies. But I had to admit that the bowl and candles looked like precisely what I’d have expected of Clay.

Mother, Eustace, and Martha appeared in the doorway as I was surveying the room.

“Very nice,” Mother said.

“I suppose it will have to do,” Eustace said.

“My thanks to whoever brought in the decorations,” I said.

“Seemed like his kind of thing,” Martha said.

“The room still needs something,” I said. I winced as soon as the words left my mouth. How many times had I heard the designers say that about a room that looked just fine to me. But in this case, I thought I was right. “The walls look pretty bare.”

“He might have been planning to leave them that way,” Eustace said. “His rooms always looked a little bare to me.”

“I think Clay would have used the words ‘uncluttered’ and ‘clean’ and ‘minimalist’ to describe his work,” Martha said.

I glanced over in surprise. She sounded almost melancholy.

“But I think Meg’s right about the room needing something,” she went on. “Not a lot—just a few well-chosen pieces of art on the walls. The problem is, without him here to do the choosing, I don’t see how we can possibly decide what.”

“Didn’t Randall find his design sketches, dear?” Mother asked. “What do they show?”

“They show art there, and there, and there.” I pointed to the three biggest bare spots. “But the art is indicated by a rough rectangle. Nothing in his almost nonexistent notes gives me any idea what he had in mind.”

“You see?” Martha said. “Impossible. We shouldn’t even try.”

“So while the room may need something,” Eustace said, “I think its needs will have to remain unfulfilled. You can’t always get what you want.”

“Martha, dear, I think you’re in a lot better position to decide what that something is than we are,” Mother said. “You’re so good at that elegant simplicity he was clearly trying to emulate. Much better than Clay, actually.”

Nicely flattered, I thought.

“Yeah.” Martha did look pleased.

“And you’ve known him longer than any of us,” Eustace added.

Martha didn’t like that as much.

“Don’t remind me,” she said. “Well, I’ll think about it. By the way, I was right, wasn’t I?”

“Right about what?” I asked.

“Clay was the one stealing the packages,” she said. “You didn’t believe me.”

“I didn’t disbelieve you,” I said. “But without any kind of proof—”

“Well, it’s water under the bridge now,” she said. “The bastard won’t be doing it again. I’ve got work to do.”

She strode out.

“Which means she’s going to ignore my request for help with the room,” I said. “Because if she did a really good job on Clay’s room, it would reduce her already small chance of winning the best room contest.”

“Her rooms are very nice,” Mother said.

“Yeah, but they’re two bathrooms and a laundry room,” I said. “You really think the judges are going to be that impressed?”

Mother nodded as if conceding my point.

“Look, you guys are busy,” I said. “I’ll take care of it.”

“You, dear?”

“Is my taste that awful?”

“No, dear, but Clay’s room isn’t very much to your taste, is it?” she said.

“True,” I said. “I thought I’d ask Vermillion for some help. They’ve both got that black-and-red color thing going on.”

Mother and Eustace both froze.

“I think she’s kidding,” Mother said, after a few moments.

“I certainly hope so,” Eustace muttered.

“I was,” I said. “Actually, I know exactly what to hang there. Clay’s own paintings.”

Mother and Eustace were silent, and obviously startled. But they didn’t ask, “What do you mean, his own paintings?” Interesting.

“I suppose that would work,” Mother said.

“Assuming you can find any of his paintings,” Eustace said. “It’s not something he’d ever have done, though. I think he was trying to forget his old life.”

“If he was trying to forget it, then why did he have some of his paintings hanging in his living room?” I asked. “At least I’m pretty sure they’re his. I saw them when the chief called me over to look at the packages Clay stole—you heard about that, right?”

They nodded.

“I don’t think he was trying to forget his old life,” I went on. “Just trying to hide it from the rest of the world.”

“Which means he’d definitely never have hung his own paintings in the show house,” Eustace said. “But now that he’s gone—why not? Can’t hurt him now. And it’s about the only thing I can think to put there that would be absolutely, undeniably his work.”

“Yes,” Mother said. “A good idea.”

“Just out of curiosity,” I went on. “Does everyone know about Clay’s checkered past?”

They exchanged a look.

“People will talk,” Mother said.

“Martha will talk,” Eustace said. “And she’s not exactly an unbiased source. I assumed she was just spreading lies about Clay until I checked with a friend who runs a gallery in New York.”

“And he confirmed her story?” I asked.

“He told me the facts, which were a lot less damning than Martha made them out to be,” Eustace said. “To hear her talk, you’d think he was a serial killer who’d gotten off with a slap on the wrist.”

“Well, she had considerable provocation,” Mother said.

“To slander the guy?”

“Slander is a little strong, don’t you think?” Mother murmured.

They went back to their rooms, still amicably debating whether Martha’s dislike of Clay had motivated her to judge his past actions too harshly. I left them to it.

I pulled out my cell phone and called the chief about getting back into the house to borrow Clay’s paintings.

“I have no objection,” he said. “But I think you should get permission from the estate first.”

“Do we even know who inherits?” I asked.

“A brother in Richmond,” the chief said. “Runs a used-car dealership there. I can give you his number.”

“Do you think it’s okay to call so soon after Clay’s death?” I asked.

“I didn’t get the feeling he was too distraught,” the chief said. “They hadn’t seen each other in five years.”

The brother was, at first, baffled by my request.

“Sure I can sell you the paintings,” he said. “If we can agree on a price. But not till we finish probating the estate, and who knows how long that will take.”

“I don’t want to buy the paintings,” I said. “I want to borrow them. To display in the show house, in the room Clay decorated.”

“Show house?”

“The last project he did before his untimely death,” I said. “As a memorial to his life and work.”

I was laying it on a bit thick, but the brother didn’t seem to be grasping the concept.

“I’m not sure we want to do that,” he said. “They could be worth something. Not my cup of tea, but for a while there he was getting a pretty high price for them.”

“Yes, but he’s fallen off the radar in the last fifteen years,” I said. “An artist needs to keep producing new work to keep people interested, and I got the impression he hasn’t been painting these last few years.”