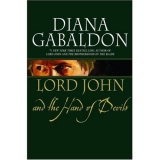

Текст книги "Lord John and the Hand of Devils"

Автор книги: Diana Gabaldon

Соавторы: Diana Gabaldon,Diana Gabaldon

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Lord John and the Hand of Devils

by Diana Gabaldon

To Alex Krislov,

Janet McConnaughey, and

Margaret J. Campbell,

sysops of the Compuserve Books and Writers Community

(http://www.community.compuserve.com/Books),

the best perpetual electronic literary cocktail party in the world. Thanks!

Foreword

In which we find A PUBLISHING HISTORY, BIBLIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION, AN AUTHOR’S NOTE, and A WARNING TO THE READER

Dear Reader—

PRELIMINARY WARNINGS

1. The book you are holding is not a novel; it’s a collection of three separate novellas.

2. The novellas in this collection all feature Lord John Grey, not Jamie and Claire Fraser (though both are mentioned now and again), but

3. I did want to assure you all that there isanother Jamie and Claire book to follow A Breath of Snow and Ashes.I usually work on more than one book at a time, and have been working on that one, too. It’s just that this one is shorter, and therefore got finished first.

Awright. Now, for those of you still with me…

Lord John Grey has been largely accidental, since the day he rashly decided to try to kill a notorious Jacobite in the darkness of the Carryarrick Pass. His association with Jamie and Claire Fraser (and with me) dates back to that passage in Dragonfly in Amber.While he did have small but important parts to play in subsequent books of the Outlander series, I really didn’t intend to write books about him on his own. (On the other hand, I never intended to show Outlander to anybody, either, and here we are. You never know, that’s all I can say.)

Lord John began his independent life apart from the Outlander books when a British editor and anthologist named Maxim Jakubowski invited me to write a short story for an anthology of historical crime that he was putting together in honor of the novelist Ellis Peters, who had recently died. Now, I had never written a short story—barring things required for English classes in school, which tended to be pretty lame—but I was fond of Ellis Peters’s Brother Cadfael mysteries, and I thought it would be an interesting technical challenge to see whether I could write something shorter than 300,000 words, so…“Why not?” I said.

It had to be the eighteenth century, because that’s the only period I know well, and I hadn’t time to research another time adequately, just for a short story. And it couldn’t involve the main characters from the Outlander series, because a good short story has high moral stakes, just as a novel does; thus, it would be difficult to write a short story involving the Frasers that would not include an event significant enough to have an impact on the plot of future novels involving them. Since I don’t think up plots in advance, I thought I’d just avoid the whole problem by using Lord John; he’s a very interesting character, he talks to me easily, and he appears only intermittently in the Outlander novels; no reason why he couldn’t be having interesting adventures offstage, on his own time.

Enter Sir Francis Dashwood and his notorious Hellfire Club, plus the murder of a red-haired man, and Lord John made his first solo appearance in a short story titled “Hellfire,” which was published in 1998 in the anthology Past Poisons,edited by Maxim Jakubowski, and published by Headline.

The stories for this anthology had a limit of 10,000 words. “Hellfire” was a hair over 12,000, but luckily nobody complained. I thought the ending was a bit rushed, even so—and so later rewrote the ending, expanding it slightly. Things turn out the same way, but with a little more style and elegance, I hope.

“Hellfire” has had an interesting publishing history, since that first appearance in Past Poisons.That anthology went out of print within a couple of years (it’s since been reprinted), which is the point at which U.S. audiences began to hear about “Hellfire” and to express interest in Lord John’s solo adventure. Unfortunately, there’s really nothing you can dowith a 14,000-word short story; it’s too long for magazine markets, much too short to be published alone.

At this fortuitous point, a couple of online acquaintances of mine decided to start an e-publishing business, and asked me whether I had “a boxful of old short stories under the bed” (Why do people think every writer begins with short stories? Or if so, that they would be willing to expose this juvenilia to the world?) that they might be able to publish.

“What the heck?” I said, figuring this was as good an opportunity as any to explore the brave new world of e-publishing. In addition to my friends’ business, the e-publishing arm of my German publishing company also decided to offer an electronic German version of “Hellfire,” and so Lord John ventured out into international cyberspace.

This was an interesting experience, and fairly successful in e-publishing terms (“success” in e-publishing terms does not generally mean quitting your day job, let’s put it like that). That experiment ended when my friends decided to list all their titles with Amazon.com—a very reasonable decision—but informed me that owing to the Amazon.com discount required of publishers, they would have to sell “Hellfire” at $6.50, in order to make any money. I couldn’t countenance the notion of selling a 23-page short story for six dollars and fifty cents, so we cordially parted ways at that point.

At this point, I began to think what else might be done with the story. It occurred to me that I’d enjoyed writing it—I like Lord John, and the complexities of his private life tend to lead him into Interesting Situations—and what if I were to write two or three more short stories involving him? Then all the short pieces could be published together in book form, and everybody would be happy. (Well, Lord John and I would, at least.)

“Hellfire” next saw print—retitled as “Lord John and the Hellfire Club”—as an add-in to the trade-paperback edition of the first Lord John Grey novel, Lord John and the Private Matter.

And here it is again,at last in book form, in company with two novellas: “Lord John and the Succubus,” which was originally written for another anthology; and “Lord John and the Haunted Soldier,” written specifically for this collection.

Other accidents happened—his lordship is prone to such things, I’m afraid—and I wrote Lord John and the Private Matter,under the delusion that this was in fact the second Lord John short story. I was informed by my literary agents, though, that in fact, I had inadvertently written a novel. (Well, how would I know? To me, a novel is just getting startedat 85,000 words.) This was good, insofar as my assorted publishers were ecstatic at the revelation that I actually couldwrite a “normal”-sized novel, and promptly gave me a contract for two more Lord John Grey novels—but it still left “Hellfire” sitting there by itself at 14,000 words.

But accidents continued to happen: I was invited to write a novella for a fantasy anthology, and presto! We had “Lord John and the Succubus,” which came in around 33,000 words. This meant that one more novella of that length or more, and we’d have critical mass.

Here, things got slightly tricky, though. By sheer happenstance, the short Lord John pieces alternated with the full-length novel: “Hellfire,” Private Matter,“Succubus.” And I had embarked on the second novel, Lord John and the Brotherhood of the Blade.All fine—but the German publisher, anxious to have the collection, asked whether I might be able to hurry up and write the final novella before finishing the second novel. Easygoing sort that I am, I said I reckoned I could do that—and I did. Allow me to note that writing a novella that follows a novel that isn’t yet written is not the easiest thing in the world, but if I wanted an easy life, I suppose I’d clean swimming pools for a living.

This collection was originally to have been titled Lord John and a Whiff of Brimstone(because of the supernatural aspect common to all the stories), but the German publisher explained that they couldn’t use that title, because my most recent Outlander novel, A Breath of Snow and Ashes,is titled Ein Hauch von Schnee und Aschein German—and German does not have separate words for “breath” and “whiff”—ergo, they’d have another Ein Hauch…and they thought one was plenty. They suggested instead, Lord John and the Hand of Devils,which I thought was wonderful, and immediately took for the English-language volume as well.

I hope you’ll enjoy it!

Best wishes,

Diana Gabaldon

Part I

A Red-Haired Man

London, 1756

The Society for Appreciation of the English Beefsteak, a gentleman’s club

Lord John Grey jerked his eyes away from the door. No. No, he mustn’t turn and stare. Needing some other focus for his gaze, he fixed his eyes instead on Quarry’s scar.

“A glass with you, sir?” Scarcely waiting for the club’s steward to provide for his companion, Harry Quarry drained his cup of claret, then held it out for more. “And another, perhaps, in honor of your return from frozen exile?” Quarry grinned broadly, the scar pulling down the corner of his eye in a lewd wink as he did so, and lifted up his glass again.

Lord John tilted his own cup in acceptance of the salute, but barely tasted the contents. With an effort, he kept his eyes on Quarry’s face, willing himself not to turn and stare, not to gawk after the flash of fire in the corridor that had caught his eye.

Quarry’s scar had faded; tightened and shrunk to a thin white slash, its nature made plain only by its position, angled hard across the ruddy cheek. It might otherwise have lost itself among the lines of hard living, but instead remained visible, the badge of honor that its owner so plainly considered it.

“You are exceeding kind to note my return, sir,” Grey said. His heart hammered in his ears, muffling Quarry’s words—no great loss to conversation.

It is not,his sensible mind pointed out, it cannot be.Yet sense had nothing to do with the riot of his sensibilities, that surge of feeling that seized him by nape and buttocks, as though it would pluck him up and turn him forcibly to go in pursuit of the red-haired man he had so briefly glimpsed.

Quarry’s elbow nudged him rudely, a not-unwelcome recall to present circumstances.

“…among the ladies, eh?”

“Eh?”

“I say your return has been noted elsewhere, too. My sister-inlaw bid me send her regard and discover your present lodgings. Do you stay with the regiment?”

“No, I am at present at my mother’s house, in Jermyn Street.” Finding his cup still full, Grey raised it and drank deep. The Beefsteak’s claret was of excellent vintage, but he scarcely noticed its bouquet. There were voices in the hall outside, raised in altercation.

“Ah. I’ll inform her, then; expect an invitation by the morning post. Lucinda has her eye upon you for a cousin of hers, I daresay—she has a flock of poor but well-favored female relations, whom she means to shepherd to good marriages.” Quarry’s teeth showed briefly. “Be warned.”

Grey nodded politely. He was accustomed to such overtures. The youngest of four brothers, he had no hopes of a title, but the family name was ancient and honorable, his person and countenance not without appeal—and he had no need of an heiress, his own means being ample.

The door flung open, sending such a draft across the room as made the fire in the hearth roar up like the flames of Hades, scattering sparks across the Turkey carpet. Grey gave thanks for the burst of heat; it gave excuse for the color that he felt suffuse his cheeks.

Nothing like. Of course he is nothing like. Who could be?And yet the emotion that filled his breast was as much disappointment as relief.

The man was tall, yes, but not strikingly so. Slight of build, almost delicate. And young, younger than Grey, he judged. But the hair—yes, the hair was very like.

Lord John Grey.” Quarry had intercepted the young man, a hand on his sleeve, turning him for introduction. “Allow me to acquaint you with my cousin by marriage, Mr. Robert Gerald.”

Mr. Gerald nodded shortly, then seemed to take hold of himself. Suppressing whatever it was that had caused the blood to rise under his fair skin, he bowed, then fixed his gaze on Grey in cordial acknowledgment.

“Your servant, sir.”

“And yours.” Not copper, not carrot; a deep red, almost rufous, with glints and streaks of cinnabar and gold. The eyes were not blue—thank God!—but rather a soft and luminous brown.

Grey’s mouth had gone dry. To his relief, Quarry offered refreshment, and upon Gerald’s agreement, snapped his fingers for the steward and steered the three of them to an armchaired corner, where the haze of tobacco smoke hung like a sheltering curtain over the less-convivial members of the Beefsteak.

“Who was that I heard in the corridor?” Quarry demanded, as soon as they were settled. “Bubb-Dodington, surely? The man’s a voice like a costermonger.”

“I—he—yes, it was.” Mr. Gerald’s pale skin, not quite recovered from its earlier excitement, bloomed afresh, to Quarry’s evident amusement.

“Oho! And what perfidious proposal has he made you, young Bob?”

“Nothing. He—an invitation I did not wish to accept, that is all. Must you shout so loudly, Harry?” It was chilly at this end of the room, but Grey thought he could warm his hands at the fire of Gerald’s smooth cheeks.

Quarry snorted with amusement, looking around at the nearby chairs.

“Who’s to hear? Old Cotterill’s deaf as a post, and the General’s half dead. And why do you care in any case, if the matter’s so innocent as you suggest?” Quarry’s eyes swiveled to bear on his cousin by marriage, suddenly intelligent and penetrating.

“I did not say it was innocent,” Gerald replied dryly, regaining his composure. “I said I declined to accept it. And that, Harry, is all you will hear of it, so desist this piercing glare you turn upon me. It may work on your subalterns, but not on me.”

Grey laughed, and after a moment, Quarry joined in. He clapped Gerald on the shoulder, eyes twinkling.

“My cousin is the soul of discretion, Lord John. But that’s as it should be, eh?”

“I have the honor to serve as junior secretary to the prime minister,” Gerald explained, seeing incomprehension on Grey’s features. “While the secrets of government are dull indeed, at least by Harry’s standards”—he shot his cousin a malicious grin—“they are not mine to share.”

“Oh, well, of no interest to Lord John in any case,” Quarry said philosophically, tossing back his third glass of aged claret with a disrespectful haste more suited to porter. Grey saw the senior steward close his eyes in quiet horror at the act of desecration, and smiled to himself—or so he thought, until he caught Mr. Gerald’s soft brown eyes upon him, a matching smile of complicity upon his lips.

“Such things are of little interest to anyone save those most intimately concerned,” Gerald said, still smiling at Grey. “The fiercest battles fought are those where very little lies at stake, you know. But what interests you, Lord John, if politics does not?”

“Not lack of interest,” Grey responded, holding Robert Gerald’s eyes boldly with his. No, not lack of interest at all.“Ignorance, rather. I have been absent from London for some time; in fact, I have quite lost…touch.”

Without intent, one hand closed upon his glass, the thumb drawing slowly upward, stroking the smooth, cool surface as though it were another’s flesh. Hastily, he set the glass down, seeing as he did so the flash of blue from the sapphire ring he wore. It might have been a lighthouse beacon, he reflected wryly, warning of rough seas ahead.

And yet the conversation sailed smoothly on, despite Quarry’s jocular inquisitions regarding Grey’s most recent posting in the wilds of Scotland and his speculations as to his brother officer’s future prospects. As the former was terra prohibitaand the latter terra incognita,Grey had little to say in response, and the talk moved on to other things: horses, dogs, regimental gossip, and other such comfortable masculine fare.

Yet now and again, Grey felt the brown eyes rest on him, with an expression of speculation that both modesty and caution forbade him to interpret. It was with no sense of surprise, though, that upon departure from the club, he found himself alone in the vestibule with Gerald, Quarry having been detained by an acquaintance met in passing.

“I impose intolerably, sir,” Gerald said, moving close enough to keep his low-voiced words from the ears of the servant who kept the door. “I would ask your favor, though, if it be not entirely unwelcome?”

“I am completely at your command, I do assure you,” Grey said, feeling the warmth of claret in his blood succeeded by a rush of deeper heat.

“I wish—that is, I am in some doubt regarding a circumstance of which I have become aware. Since you are so recently come to London—that is, you have the advantage of perspective, which I must necessarily lack by reason of familiarity. There is no one…” He fumbled for words, then turned eyes grown suddenly and deeply unhappy on Lord John. “I can confide in no one!” he said, in a sudden, passionate whisper. He gripped Lord John’s arm, with surprising strength. “It may be nothing, nothing at all. But I must have help.”

“You shall have it, if it be in my power to give.” Grey’s fingers touched the hand that grasped his arm; Gerald’s fingers were cold. Quarry’s voice echoed down the corridor behind them, loud with joviality.

“The ’Change, near the Arcade,” Gerald said rapidly. “Tonight, just after full dark.” The grip on Grey’s arm was gone, and Gerald vanished, the soft fall of his hair vivid against his blue cloak.

Grey’s afternoon was spent in necessary errands to tailors and solicitors, then in making courtesy calls upon long-neglected acquaintance, in an effort to fill the empty hours that loomed before dark. Quarry, at loose ends, had volunteered to accompany him, and Lord John had made no demur. Bluff and jovial by temper, Quarry’s conversation was limited to cards, drink, and whores. He and Grey had little in common, save the regiment. And Ardsmuir.

When he had first seen Quarry again at the club, he had thought to avoid the man, feeling that memory was best buried. And yet…could memory be truly buried, when its embodiment still lived? He might forget a dead man, but not one merely absent. And the flames of Robert Gerald’s hair had kindled embers he had thought safely smothered.

It might be unwise to feed that spark, he thought, freeing his soldier’s cloak from the grasp of an importunate beggar. Open flames were dangerous, and he knew that as well as any man. And yet…hours of buffeting through London’s crowds and hours more of enforced sociality had filled him with such unexpected longing for the quiet of the North that he found himself filled suddenly with the desire to speak of Scotland, if nothing more.

They had passed the Royal Exchange in the course of their errands; he had glanced covertly toward the Arcade, with its gaudy paint and tattered posters, its tawdry crowds of hawkers and strollers, and felt a soft spasm of anticipation. It was autumn; the dark came early.

They were near the river now; the noise of clamoring cockle-sellers and fishmongers rang in the winding alleys, and a cold wind filled with the invigorating stench of tar and wood shavings bellied out their cloaks like sails. Quarry turned and waved above the heads of the intervening throng, gesturing toward a coffeehouse; Grey nodded in reply, lowered his head, and elbowed his way toward the door.

“Such a press,” Lord John said, pushing his way after Quarry into the relative peace of the small, spice-scented room. He took off his tricorne and sat down, tenderly adjusting the red cockade, knocked askew by contact with the populace. Slightly shorter than the common height, Grey found himself at a disadvantage in crowds.

“I had forgot what a seething anthill London is.” He took a deep breath; grasp the nettle, then, and get it over. “A contrast with Ardsmuir, to be sure.”

“I’d forgot what a misbegotten lonely hellhole Scotland is,” Quarry replied, “until you turned up at the Beefsteak this morning to remind me of my blessings. Here’s to anthills!” He lifted the steaming glass which had appeared as by magic at his elbow, and bowed ceremoniously to Grey. He drank, and shuddered, either in memory of Scotland or in answer to the quality of the coffee. He frowned, and reached for the sugar bowl.

“Thank God we’re both well out of it. Freezing your arse off indoors or out, and the blasted rain coming in at every crack and window.” Quarry took off his wig and scratched his balding pate, quite without self-consciousness, then clapped it on again.

“No society but the damned dour-faced Scots, either; never had a whore there who didn’t give me the feeling she’d as soon cut it off as serve it. I swear I’d have put a pistol to my head in another month had you not come to relieve me, Grey. What poor bugger took over from you?”

“No one.” Grey scratched at his own fair hair abstractedly, infected by Quarry’s itch. He glanced outside; the street was still jammed, but the crowd’s noise was mercifully muffled by the leaded glass. One sedan chair had run into another, its bearers knocked off balance by the crowd. “Ardsmuir is no longer a prison; the prisoners were transported.”

“Transported?” Quarry pursed his lips in surprise, then sipped, more cautiously. “Well, and serve them right, the miserable whoresons. Hmm!” He grunted, and shook his head over the coffee. “No more than most deserve. A shame for Fraser, though—you recall a man named Fraser, big red-haired fellow? One of the Jacobite officers—a gentleman. Quite liked him,” Quarry said, his roughly cheerful countenance sobering slightly. “Too bad. Did you find occasion to speak with him?”

“Now and then.” Grey felt a familiar clench of his innards, and turned away, lest anything show on his face. Both sedan chairs were down now, the bearers shouting and shoving. The street was narrow to begin with, clogged with the normal traffic of tradesmen and ’prentices; customers stopping to watch the altercation added to the impassibility.

“You knew him well?” He could not help himself; whether it brought him comfort or misery, he felt he had no choice now but to speak of Fraser—and Quarry was the only man in London to whom he could so speak.

“Oh, yes—or as well as one might know a man in that situation,” Quarry replied offhandedly. “Had him to dine in my quarters every week; very civil in his speech, good hand at cards.” He lifted a fleshy nose from his glass, cheeks flushed ruddier than usual with the steam. “He wasn’t one to invite pity, of course, but one could scarce help but feel some sympathy for his circumstances.”

“Sympathy? And yet you left him in chains.”

Quarry looked up sharply, catching the edge in Grey’s words.

“I may have liked the man; I didn’t trust him. Not after what happened to one of my sergeants.”

“And what was that?” Lord John managed to infuse the question with no more than light interest.

“Misadventure. Drowned by accident in the stone-quarry pool,” Quarry said, dumping several teaspoons of rock sugar into a fresh glass and stirring vigorously. “Or so I wrote in the report.” He looked up from his coffee, and gave Grey his lewd, lopsided wink. “I liked Fraser. Didn’t care for the sergeant. But never think a man is helpless, Grey, only because he’s fettered.”

Grey sought urgently for a way to inquire further without letting his passionate interest be seen.

“So you believe—” he began.

“Look,” said Quarry, rising suddenly from his seat. “Look! Damned if it’s not Bob Gerald!”

Lord John whipped round in his chair. Sure enough, the late-afternoon sun struck sparks from a fiery head, bent as its owner emerged from one of the stalled sedan chairs. Gerald straightened, face set in a puzzled frown, and began to push his way into the knot of embattled bearers.

“Whatever is he about, I wonder? Surely—Hi! Hold! Hold, you blackguard!” Dropping his glass unregarded, Quarry rushed toward the door, bellowing.

Grey, a step or two behind, saw no more than the flash of metal in the sun and the brief look of startlement on Gerald’s face. Then the crowd fell back, with a massed cry of horror, and his view was obscured by a throng of heaving backs.

He fought his way through the screaming mob without compunction, striking ruthlessly with his sword hilt to clear the way.

Gerald was lying in the arms of one of his bearers, hair fallen forward, hiding his face. The young man’s knees were drawn up in agony, balled fists pressed hard against the growing stain on his waistcoat.

Quarry was there; he brandished his sword at the crowd, bellowing threats to keep them back, then glared wildly round for a foe to skewer.

“Who?” he shouted at the bearers, face congested with fury. “Who’s done this?”

The circle of white faces turned in helpless question, one to another, but found no focus; the foe had fled, and his bearers with him.

Grey knelt in the gutter, careless of filth, and smoothed back the ruddy hair with hands gone stiff and cold. The hot stink of blood was thick in the air, and the fecal smell of pierced intestine. Grey had seen battlefields enough to know the truth even before he saw the glazing eyes, the pallid face. He felt a deep, sharp stab at the sight, as though his own guts were pierced, as well.

Brown eyes fixed wide on his, a spark of recognition deep behind the shock and pain. He seized the dying man’s hand in his, and chafed it, knowing the futility of the gesture. Gerald’s mouth worked, soundless. A bubble of red spittle swelled at the corner of his lips.

“Tell me.” Grey bent urgently to the man’s ear, and felt the soft brush of hair against his mouth. “Tell me who has done it—I will avenge you. I swear it.”

He felt a slight spasm of the fingers in his, and squeezed back, hard, as though he might force some of his own strength into Gerald; enough for a word, a name.

The soft lips were blanched, the blood bubble growing. Gerald drew back the corners of his mouth, a fierce, tooth-baring rictus that burst the bubble and sent a spray of blood across Grey’s cheek. Then the lips drew in, pursing in what might have been the invitation to a kiss. Then he died, and the wide brown eyes went blank.

Quarry was shouting at the bearers, demanding information. More shouts echoed down the walls of the streets, the nearby alleys, news flying from the scene of murder like bats out of hell.

Grey knelt alone in the silence near the dead man, in the stench of blood and voided bowels. Gently, he laid Gerald’s hand limp across his wounded breast, and wiped the blood from his own hand, unthinking, on his cloak.

A motion drew his eye. Harry Quarry knelt on the other side of the body, his face gone white as the scar on his cheek, prying open a large clasp knife. He searched gently through Gerald’s loosened, blood-matted hair, and drew out a clean lock, which he cut off. The sun was setting; light caught the hair as it fell, a curl of vivid flame.

“For his mother,” Quarry explained. Lips tightly pressed together, he coiled the gleaming strand and put it carefully away.

Part II

Intrigue

The invitation came two days later, and with it a note from Harry Quarry. Lord John Grey was bidden to an evening’s entertainment at Joffrey House, by desire of the Lady Lucinda Joffrey. Quarry’s note said simply, Come. I have news.

And not beforetimes,Grey thought, tossing the note aside. The two days since Gerald’s death had been filled with frantic activity, with inquiry and speculation—to no avail. Every shop and barrow in Forby Street had been turned over thoroughly, but no trace found of the assailant or his minions; they had faded into the crowd, anonymous as ants.

That proved one thing, at least, Grey thought. It was a planned attack, not a random piece of street violence. For the assailant to vanish so quickly, he must have looked like hoi polloi; a prosperous merchant or a noble would have stood out by his bearing and the manner of his dress. The sedan chair had been hired; no one recalled the appearance of the hirer, and the name given was—not surprisingly—false.

He shuffled restlessly through the rest of the mail. All other avenues of inquiry had proven fruitless so far. No weapon had been found. He and Quarry had sought the hall porter at the Beefsteak, in hopes that the man had heard somewhat of the conversation between Gerald and Bubb-Dodington, but the man was a temporary servant, hired for the day, and had since taken his wages and vanished, no doubt to drink them.

Grey had canvassed his acquaintance for any rumor of enemies, or failing that, for any history of the late Robert Gerald that might bear a hint of motive for the crime. Gerald was evidently known, in a modest way, in government circles and the venues of respectable society, but he had no great money to leave, no heirs save his mother, no hint of any romantic entanglement—in short, there was no intimation whatever of an association that might have led to that bloody death in Forby Street.

He paused, eye caught by an unfamiliar seal. A note, signed by one G. Bubb-Dodington, requesting a few moments of his time, in a convenient season—and noting en passantthat B-D would himself be present at Joffrey House that evening, should Lord John find himself likewise engaged.

He picked up Quarry’s note again, and found another sheet of paper folded up behind it. Unfolded, this proved to be a broadsheet, printed with a poem—or at the least, words arranged in the form of verse. “A Blot Removed,” it was titled. Lacking in meter, but not in crude wit, the doggerel gave the story of a “he-whore” whose lewdities outraged the public, until “scandal flamed up, blood-red as the abominable color of his hair,” and an unknown savior rose up to destroy the perverse, thus wiping clean the pristine parchment of society.

Lord John had eaten no breakfast, and sight of this extinguished what vestiges he had of appetite. He carried the document into the morning room, and fed it carefully to the fire.

Joffrey House was a small but elegant white stone mansion, just off Eaton Square. Grey had never come there before, but the house was well known for brilliant parties, much frequented by those with a taste for politics; Sir Richard Joffrey, Quarry’s elder half brother, was influential.