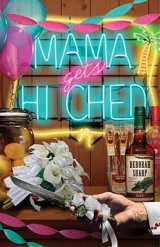

Текст книги "Mama Gets Hitched"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Женский детектив

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

As Tony and I approached the wooden walkway outside the park’s office, I could barely believe who was among the nature walkers milling about.

The usual retirees were there, sporting bright clothes and sunburns. There was a serious-looking, thirtyish couple; binoculars around his neck, Birds of Florida in her hand. And there was the mystery woman from the bar at the Speckled Perch, outfitted again in dark glasses and black leather.

I greeted everyone, exchanged introductions, and outlined where the wooden boardwalk would take us. Then I addressed Ms. Sunglasses.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your name.”

“Jane Smith.”

Yeah, right, I thought. “Would you like to leave that in the office?” I gestured to the motorcycle helmet she carried.

Clasping it tightly to her side, she shook her head. “S’fine.”

“Everybody ready to spot some wildlife then?”

My answer was a chorus of yeses and smiles from the seniors and Tony, and nods from the birdwatchers. The sunglasses seemed to aim past me into the distance. No acknowledgment, not even a head nod. Not exactly Ms. Congeniality. She’d certainly seemed friendly enough last night, chatting up Carlos in the bar.

Maybe she was hung over because they’d stayed up all night, drinking and yakking. My stomach clenched like a fist. It surprised me how much it hurt to think that maybe talking wasn’t all the two of them had done.

We started out on the walk. It had to be one of the strangest I’d ever given. I always tried to draw out the visitors, asking folks where they came from originally. Few locals from this part of Florida would voluntarily walk through the woods in June at sunset unless there was the promise of shooting something, too.

On this walk, I got back a Pennsylvania, a few Ohios, and a Michigan. Tony piped up with New Jersey from the back.

We all turned to Ms. Sunglasses, waiting for her answer. Her lips opened just wide enough to mutter two words, “All over,” before she pressed them shut again.

She made Darryl from the fish camp look like a motor mouth.

Stone-faced and silent, she hung back from the rest of the group. Which would have been fine, if she’d shown the slightest interest in taking in the view from the boardwalk. But she seemed more intent on watching us than observing nature. I couldn’t say for sure, though. Despite the darkening sky, she never removed the sunglasses. And she didn’t participate, not even when I called the walkers to a railing to see a huge gator lolling in the swamp below the boardwalk.

“How big is he?” one of the Ohioans asked. Flashes went off on digital cameras.

“A ten-footer, at least,” I said. “A good way to tell, if all you spot is his head above water, is to estimate the number of inches from his eyes to the tip of his snout. His body will be about the same number in feet. Course, if we weren’t on this boardwalk, and he was close enough for you to count inches, you might never get the chance to tell anyone else how big he was.”

Everyone laughed but Ms. Sunglasses. She leaned against a far railing, regarding me with a frown.

A little farther on, we came to a hardwood hammock. I pointed out a cardinal flitting by, and a delicate air plant nestled high in a crook of an oak tree. “A lot of people think air plants are parasites, but they’re not. They don’t get nutrition from the tree; they only use it for support, like a trellis.”

“Do the alligators eat the air plants?”

The birdwatchers snickered at the question. Remembering Rhonda’s warning, I looked down at the water, and then way up high to the tree. I forced a smile for the gent from Ohio.

“No, sir. Gators definitely prefer the meat course to the salad bar.”

“Aren’t orchids air plants, too?” asked one of the retiree wives, from Pennsylvania.

I glanced across the boardwalk. Ms. Sunglasses stood rigidly, dark lenses pointing my way.

I answered, “Yep, orchids and Spanish moss, too. Air plants are also called epi … epi … epiphytes.”

As I stumbled over a word I’d used dozens of times before, I knew the mystery woman was making me nervous. And I wasn’t alone. The seniors watched her furtively, taking in her biker regalia. Tony kept looking over his shoulder, as nervous as a seventeen-year-old trying to buy beer. Only the birders seemed unconcerned by her lurking about like a nature-walk spy. They were too busy sharing binoculars and jotting field notes to notice her odd behavior.

I was relieved when the hour was finally up, and I could bid the whole group goodbye. Tony thanked me, and then hurried off with the rest of the group toward the parking lot. The biker woman hung back, aiming her sunglasses at the upcoming programs on the bulletin board.

Was she reading them? I couldn’t be sure. I prayed she wouldn’t return for any of the events I led. She gave me the creeps.

“I’m about to close up the park,” I finally said to her. “Can I help you with anything?”

“Jane Smith” shook her head without turning, and took her time finishing up at the board. Then, suddenly, she spun around and left without a word. She moved across the deck like a Florida panther, surprisingly quick and silent for a woman in big black motorcycle boots.

Fishing for my keys in the pocket of my work pants, I watched as she followed a curve in the path. She disappeared into the shadowy woods. I wanted to be sure she was gone before I turned my back to unlock the door. Staring hard into the woods, I listened for what seemed like a long time. The voices of the walkers grew faint as they reached the parking lot. The doors on the retirees’ van slid open and closed. Two car doors slammed; the birdwatchers, no doubt.

I waited, straining to catch any other sounds.

Just then, my cell phone rang on my belt, startling me. I answered, and it took me a couple of moments of spotty reception to realize it was a phone solicitation. Cursing, I cut off the call.

Seconds later, a motorcycle engine roared to life. Ms. Sunglasses, I presumed. She revved it and took off, shifting gears on her way out of the park. I heard the bike slow, then pull onto the highway, and accelerate again.

Feeling silly, I let out the breath I’d been holding.

As I listened to the motor’s rumble, growing distant, I realized I never heard the slam of a single door on the last car in the lot. What had happened to Tony?

_____

The sun’s final rays were sinking behind the trees. Darkness was approaching fast.

I’d done one last check on the animals, and set the answering machine to take incoming calls. As I prepared to leave, I slipped bug spray into one pocket, and a flashlight into the other. Then I grabbed a heavy club we keep by the door, just in case we run across a wild hog defending its territory or offspring.

As soon as I walked outside, mosquitoes circled and whined, hungry for blood. I sprayed the repellent into my hands, and rubbed them across my face. All I needed was some honking big mosquito bite on my bridesmaid’s nose to ruin Mama’s Special Day.

We never held the sunset walks during summer, because it gets too wet and too buggy. Couldn’t find enough masochists to show up. I enjoyed a silent chuckle, envisioning tender-skinned visitors slapping and dancing on the boardwalk in August, and started onto the path to the parking lot.

I was well into the woods when I heard a rustle in the brush.

Of course, it was just an animal of some sort. This time of day, they’re either settling down somewhere safe for the night, or starting out to look for smaller prey. An image flashed through my mind of the mystery woman, and that big motorcycle helmet. That could surely do some damage if she decided to go on a hunt for prey.

The park was alive with familiar sounds: the breeze sighed in the trees; a gator grunted from Himmarshee Creek; small things scurried through palmetto scrub and dead leaves. As I wended my way toward the distant lot, I thought I heard a less familiar sound. Almost like a ragged breath. I shined my flashlight into the deeper woods. All I saw were trees.

And then I heard it again, distinctly. Rapid breathing, like after physical exertion. In and out; in and out.

“Who’s there?” The breathing halted. No animal knew enough to do that. “Tony?”

No answer. I tightened my grip on the club, and began to walk a little faster.

“Mama? It’s Mace.”

“Honey, where are you?” Her pout was audible over the cell line. “I thought we could go over the order of the toasts for the reception one more time.”

Please, God. No.

“I don’t think so, Mama. I’m on the highway on my way home from work. I’m running late, and I’m beat.”

I’d made it to the parking lot without incident. Tony’s car was gone. Maybe the breathing I thought I heard in the woods was just a trick of the wind through the trees.

When Mama didn’t respond, I said into the phone, “Remember that strange woman Carlos was talking to last night at the Perch? In the bar?”

“Of course I do, Mace. She’d be kind of hard to forget, what with all that black leather. Now, not every woman could carry off that much black. But with her blond hair and that gorgeous shape, I have to admit it looked terrific on her.”

Thanks, Mama, I thought. Just what I needed to hear.

“Anyway,” I said, “that same woman showed up at the park this afternoon for the sunset walk.”

“Was she wearing black again? You know, if she’d just add a colorful scarf in an accent color, she would really have a great look. Maybe turquoise, or aqua, even pink, with that mass of blond curls. Was she wearing …”

I cut Mama off. “Yes, she was in black. No, there was no scarf. Now, if we can move on from the fashion segment, I’d like to give you the rest of my news.”

“I’m all ears, Mace. Though I must say it wouldn’t kill you to pay just the smallest bit of attention to fashion. If you’d just put on a little lipstick now and then …”

My knuckles were showing white on the steering wheel. “Mama!”

“Oh, all right.” The pout was back. “What’s your news?”

I was going to tell her all about Tony showing up, and me raising the topic of his family. But at just that moment, I saw an oncoming car fast approaching the little bridge over Taylor Slough. State Road 98 narrowed at the bridge, and the highway demanded my full attention.

“Hang on, Mama. I’m driving over Buzzard Bridge.”

The spot earned its name because so many wrecks had occurred that the buzzards hung out, waiting for carnage.

“Mace, be careful!”

I edged to the right and slowed a bit, as the other car blew past me with just a foot or so to spare. There was still enough twilight, and we were close enough, that I could see the driver’s eyes. They were wide with fear under the brim of his Walt Disney World cap. Maybe he’d ratchet down the gas pedal on that rental car when he came to the next narrow crossing.

“Okay,” I began, before I was immediately distracted again.

This time, it was a scene in a thicket of trees alongside the road. A tall blonde stood beside a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Black, of course. A big, fancy car was parked right next to the bike. The car gleamed, golden, under my headlights. A heavy-set man with a cigar in his mouth leaned casually against the driver’s side door. The car was a very distinctive Cadillac.

“Well, that was weird,” I muttered as I sped past.

“What’s weird, Mace? Would you please speak up? It’s really hard to hear you on that cello-phone.”

“I just saw Sal, pulled way off on the shoulder along 98. He was talking to that same blond woman from the bar.”

Mama gasped. Apparently she had no trouble hearing me now.

“Well, you have to turn around and go back there! Find out what Sal’s doing out in the woods with some gorgeous young gal.”

I looked in the rearview mirror. There was nothing but dark road behind me. “They’re not exactly in the woods, Mama.”

“Woods, highway, whatever. Turn around right now, Mace.”

I hesitated. Mama already had talked me into a god-awful, ruffled mess for Saturday, wearing a most likely horrifying hairdo, and carrying the most ridiculous parasol known to womankind. It’d cost me, but I decided this request was going to be my line in the sand.

“No, Mama. I will not turn around. It’s been a long day. I’m tired, and I’m hungry. You can ask Sal yourself why he was out here along the road with her.”

I didn’t add that the thought of any kind of confrontation with Ms. Sunglasses made me nervous. She was strange; she was just as big as me; and that helmet looked plenty heavy.

“Well!” Mama’s exhale was full of indignation. “I’d certainly do it for you, Mace.”

Did I dare go there? Ah, what the hell.

“I know, Mama. And that’s the difference between us.”

“Excuse me?”

“I’d never want you to do it for me. You’re acting like you’re in junior high, sending another girl over to the lunch table to find out if some boy still likes you. For God’s sake, you’re a grown woman! You’re going to marry the man on Saturday.”

There was a long pause on the phone. “This connection must be real bad. I thought I just heard you disrespecting your mama.”

“No disrespect intended. I’m just saying you should talk to Sal. I’m not going to be your go-between.”

“Fine!”

“Good.”

I was gaining on a slow-moving truck, hauling a noisy cargo. An awful smell wafted toward me on the night air.

“Whew! I’m coming up on a truck full of hogs and a double center line, Mama. I need to get off the phone and pay attention so I can pass this old boy who’s driving as soon as I get the chance.”

There was silence on the other end.

“Mama? Did you hear me?”

“What if Sal is like No. 2, Mace? What if he’s like him?” Her voice had turned small, shaky.

I felt a rush of sympathy. Number 2 was by far the worst of Mama’s ex-husbands. He’d started cheating within days of their marriage, taking up with a cocktail waitress from the casino hotel where they honeymooned in Las Vegas. After that, there’d been a long and humiliating procession of Other Women.

I eased off the gas a bit, letting the smelly truck gain some distance. “Mama, Sal is a good man.”

“Maybe too good to be true.”

“Now, you know that’s not right. Sal is nothing like No. 2. Just talk to him. I’m sure there’s a reasonable explanation.”

She sighed, a sound heavy with remembered pain. “I could never go through it again, Mace.”

“I know, Mama. You’re just having pre-wedding jitters, that’s all. Everything is going to be all right, I know it. You and Sal are going to be as happy as Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara.”

There was a long pause from Mama’s end.

“You didn’t watch that movie I loaned you, did you, honey?”

“No. Why?”

“Because Rhett walks out on Scarlett in the end.”

A claw-like hand landed on my right shoulder. Maddie shrieked from the backseat of Pam’s VW. “Watch where you’re going, Mace! You nearly knocked over my manatee mailbox.”

“Sorry,” I muttered.

Mama had sounded so upset, I decided to round up my sisters and pay a visit for moral support. We’d just picked up Maddie, and we were enroute to Mama’s now. Marty was in the front, like always, because she’s prone to carsickness. Maddie was in the back seat because, well, who ever heard of a front-seat driver?

Grinning at me, Marty leaned over to extract Maddie’s fingernails from my shoulder.

“You know, Mace …” My big sister settled back into the seat, but her tone said she wasn’t ready to let an opportunity for further criticism pass her by. “God gave us rearview mirrors for a reason.”

I glanced at Marty and rolled my eyes. She giggled.

“Actually, Maddie, some racecar driver in 1911 at the first Indianapolis 500 gave us rearview mirrors,” I said.

Maddie harrumphed. “Nobody likes a know-it-all, Mace. And God surely put the idea into that driver’s head.”

“You’re probably right, Maddie. But just so you know, I missed that ugly mailbox of yours by a mile.”

Maddie was about to start another round when Marty said, “Sisters, enough! Now that we’re all here, Mace, what were you going to tell us about Sal?”

I filled them in on seeing him with Ms. Sunglasses, and how Mama had some kind of flashback to the bad old days with Husband No. 2. We were used to the Mama Drama, but we also knew the awful toll that second marriage had taken on her.

“It’s post-traumatic stress,” Maddie said with certainty.

“Thank you, Dr. Laura,” I said.

“I mean it, Mace. She’s facing the same set of circumstances—getting married. Now, she’s reliving the anguish of getting hitched to the wrong man, and wondering if she’s making the same mistake again.”

“So why didn’t she go through that with Nos. 3 and 4?” Marty asked.

“The same stimuli never presented themselves,” Maddie said. “It’s as simple as that.”

Along with her college French, Maddie also took a few psychology courses. Who’s the know-it-all now?

“Sounds like a bunch of hooey to me, Maddie,” I said. “Mama’s probably just over-reacting, as usual.”

Marty twisted a long strand of hair around her finger. “How bad did she sound?”

“Hard to tell on the cell, Marty. That’s why I wanted us to go see her. Y’all know how rash Mama can be. I just don’t want her to do something crazy.”

“Wouldn’t be the first time,” Maddie said.

“Remember when she got into a fistfight at a party with that one woman No. 2 was running around with?” I asked my sisters.

“Those were some good deviled eggs that gal brought, though,” Maddie said.

I nodded. “Yeah, it was a shame the whole platter ended up on the floor, with Mama and the hussy rolling around in them like wrestlers on TV.”

Marty sighed. “She was cleaning stains off that sherbet-colored pantsuit for days.”

I turned on the radio, classic country. Tammy Wynette was singing “Stand by Your Man,” a real oldie. We made it onto Main Street, and almost to the song’s chorus before another shriek rattled the windows from the back.

“Great Uncle Elmer gone to heaven, Mace! Didn’t you see that woman stepping out of her car at that parking spot? You came so close you about took her door off.”

The more Maddie picked, the heavier my foot felt on the accelerator. Childish, I know. But I hated having my driving criticized. Especially when everybody in Himmarshee County knew to clear out of the way when Maddie Wilson got behind the wheel. I gunned the VW, which whined in protest.

“Speed limit’s thirty-five, Mace.”

Marty’s quiet, reasonable voice made me realize what a baby I was being. Lifting my foot off the gas, I looked in the rearview at Maddie. “Sorry.”

“Humph!” Maddie crossed her arms over her chest.

None of us spoke for the next few minutes. Soon, I turned onto Strawberry Lane. As we passed by Alice’s house, I saw the drapes at her front windows were still drawn. The porch light shone on her flower pots, filled with sad, wilting plants. If Mama weren’t so preoccupied with The Wedding of the Century, she’d surely have been next door to her neighbor’s, seeing to poor Alice and her dying geraniums.

I eased the VW into Mama’s drive. “Well, sisters, we’ll know soon enough if this is Mama as Usual or Red Alert,” I said.

As we piled out of the car, Teensy’s high-pitched barking sounded through the open windows. You’d think that crazy dog would recognize the three of us by now. I swear he barked like that just to annoy me.

“Teensy!” Mama shouted. “Shut the hell up!”

The three of us nearly dropped in our tracks between the pittosporum hedges on Mama’s front path. The S-word and cursing?

“Uh-oh,” Marty breathed.

“Uh-oh is right,” Maddie echoed.

The front door flung open. Mama stood on the other side, the squirming dog in her arms. Her eyes were red and puffy; her platinum-hued ’do a collapsed soufflé. She was missing one of her raspberry-sherbet colored shoes, and her big toe stuck out of a huge run in the foot of her knee-high stocking.

She burst into tears.

“Girls, the wedding is off!”

Marty couldn’t help it. She giggled. She does that sometimes when she’s nervous. Looking horrified, she clamped a hand over her mouth. But the more she tried to hold back, the harder her shoulders shook with suppressed laughter.

“Sorry, Mama,” she managed to squeak out.

The look Maddie aimed at our little sister could have formed icebergs on Lake Okeechobee. “I don’t see what’s so funny, Marty.”

Marty couldn’t speak. Her knees had gone weak. She propped herself against the frame of the front door and simply pointed into the foyer at Mama and Teensy. The harder Mama cried, the louder the little dog yowled. The two of them sounded like the most talentless duo ever kicked off America’s Got Talent.

“S-s-so glad I could a-a-amuse you, Marty.” Mama hiccupped accusingly. “Maybe when the remainder of my life falls apart, you can get your sisters in on the joke, too.”

Mama plastered a haughty look on her face and pulled herself up to her full height, four-foot-eleven inches. But it’s kind of hard to project dignity when you’re absent one shoe, your mascara has melted into raccoon eyes, and a Pomeranian is trying to wriggle out from the armpit of your raspberry-hued jacket. I felt a chuckle coming on, too.

“Oh, for God’s sake!” Maddie pushed past us through Mama’s front door. “The both of you are completely useless.”

“Are not!” Marty and I said at the same time, which kicked my chuckle into all-out laughter.

Maddie wrapped a protective arm around Mama’s slender shoulders, and then glared at us over the top of our mother’s smooshed ’do. Marty and I only laughed harder.

The next thing we knew, Mama and Maddie had turned their backs on us. The foot with the raspberry shoe kicked out to the door, slamming it in our faces. I heard the deadbolt lock rotate with force.

“You can join us when you learn some manners,” Maddie called out through the open window.

I raised my eyes to Marty’s. The guilty look on her face probably mirrored my own. Our ill-timed guffaws had run their course. Like school kids sensing real trouble on the bench outside the office, we took a few moments to compose ourselves. Then I knocked at the door.

“May we come in now?” I tried to make my voice sound serious. Mature.

Marty leaned to the window and added, “We promise to be good.”

Heavy steps vibrated on the other side of the door. Maddie. I didn’t hear the dog’s paws scrabbling over the floor, though. Teensy was probably with Mama in the kitchen, sulking.

“Beautiful timing, sisters,” Maddie hissed as she opened the door. “Now Mama is sad and mad. She’s furious at you two.”

Mad was good, I thought. I’d rather see her angry than moping and beaten down like she became in that last year of her marriage to No. 2. Marty and I arranged our faces into appropriately chastened expressions. We slunk in behind Maddie as she led the way into Mama’s kitchen.

“Good evening, girls.” Mama’s tone was frosty.

“Evening, Mama.” We tried to sound contrite.

Marty and I silently took our seats. A box of pink wine sat on the kitchen table. The glass in front of Mama was half full. Maddie was busy, putting out gingham-checked placemats, and pulling more glasses from the cabinets. I waited as she poured our wine, and drew a tumbler of tap water for herself. Mama kept her eyes on the table, fiddling with a ceramic salt shaker shaped like a duck. Still sniffling a bit, she traced the line of the duck’s yellow-gingham collar.

I caught Maddie’s eye and gave a slight nod toward Mama’s wine glass. Maddie slid it under the box’s pour spout and filled it to the brim. When the rest of us had taken our first sips, I broke the silence.

“Mama, you can’t possibly mean you’re backing out of the wedding. Surely this is something we can work out?”

Silently, she lifted the tail end of a raspberry-sherbet scarf she wore around her neck and dabbed at her mascara-muddied eyes. I hoped the scarf wasn’t Dry Clean Only.

Marty tore off a piece of paper towel from the roll on the table. Maddie fished a compact out of her purse and handed it to Mama. Never one to ignore the presence of a mirror, she popped it open to take a peek.

“Jesus H. Christ on a crutch.” Mama snapped the compact shut like it caught fire. “I look a fright.”

“It’s not that bad,” I said loyally.

“It’s mainly the mascara,” Marty added.

“That and your hair,” Maddie pointed out helpfully.

Mama opened the mirror again. “I always said I’d never cry over another man, girls. And here I am.” Examining the damage, she fluffed her hair’s flattest side and picked off mascara clumps with the paper towel. She extracted her Apricot Ice lipstick from her pantsuit pocket, and swiped it twice across her lips.

Then she handed the compact back to Maddie, took a big swallow of wine, and squared her shoulders. “Enough is enough,” she said.

I didn’t like the final sound of that.

“What happened, Mama?” I glanced at the swiveling hips on her Elvis wall clock. “It’s barely been an hour-and-a-half since we talked. How could Sal go from the love of your life to the scum of the earth in such a short time?”

She took another big swig of wine, not even bothering to blot the lipstick stain off the glass. “Plain and simple, girls,” Mama said. “He’s a liar.”

My sisters and I looked at each other. When Mama gets that made-up-her-mind tone, it’s easier to push a Brahma bull up a steep hill than it is to get her to see any alternatives.

Marty shook her head. “I’ve never known Sal to lie.”

“Well, then, you don’t know him very well, Marty, because he flat-out lied to me about that woman Mace saw him parking with.”

“They were just standing there. They weren’t ‘parking,’ Mama.”

An imaginary picture immediately popped into my head of Sal and Ms. Sunglasses wrestling like horny teenagers on the roomy seat of his Cadillac. Now I’d have to recite the first several stanzas of “ ’Twas the Night Before Christmas” to banish the image from my mind.

“Well, whatever they were doing, he denied even being out there at all. And he kept trying to get me off the phone, like I was annoying him for even asking.”

She swallowed more wine, and stared out the window into the night. When Mama spoke again, her voice was soft and distant. “I’m telling you, girls, Sal sounded just like Husband No. 2. I remember it so well, this one time when I called to check on him when he was home sick from work. That lying S.O.B. couldn’t get me off the phone fast enough. I found out later he wasn’t sick at all that day. Number 2 had some hoochie-mama from an Orlando strip club in my bed at the exact moment I called.”

My heart went out to her. We’d all known No. 2 was a rat. But we were still young when they were married. She’d never shared those kinds of carnal details.

“That’s awful.” Marty put a hand over Mama’s on the table.

Mama shrugged. “That wasn’t the first time. Wouldn’t be the last.”

Maddie topped off her glass of wine.

“Maybe it wasn’t Sal out on the road,” Marty said, but even she sounded doubtful. “Are you certain you saw them, Mace?”

Maddie snorted. “Mace can pick out a hawk on a pine branch at fifty yards and tell you if it’s a red-tailed or a red-shouldered. And Sal is a lot bigger than a hawk.”

“Yeah, he’s more like a buzzard,” Mama said.

Now she was name-calling. I just wished I’d turned around on that highway and checked on Sal and Sunglasses, like Mama asked me to. We’d have the real story, and her imagination wouldn’t have had a chance to spin out of control.

We all fell silent, each with our thoughts. Then, Maddie got up to rummage around in the refrigerator. She returned with three-fourths of a butterscotch pie in one hand and two take-out containers from the Pork Pit in the other. I rose to get out some plates and silverware, while Marty slipped the take-out into the microwave.

“I couldn’t eat a thing,” Mama said. “I’m too upset.”

Maddie cut her a small slice of the pie anyway. Mama pushed the plate way off to the side of her placemat, even though butterscotch was her favorite.

Once my sisters and I had filled our plates, Maddie announced: “Well, I like Sal. I’m not going to believe the worst about him until I hear what he has to say.”

Last summer, Maddie’s attitude toward Sal had been the last to change. But once he won her over, she was in his corner for life. Even if he was a New Yorker.

Marty defended him, too. “Can’t you give Sal the benefit of the doubt, Mama? Remember there were a lot of things he wouldn’t—couldn’t—tell us last summer. But everything turned out all right in the end, didn’t it?”

Mama didn’t answer. Marty’s question hung in the air, which was rich with the tangy smell of barbecue sauce, the aroma of macaroni and cheese, and the sweet scent of that pie, topped with a mountain of whipped cream.

Mama’s fork darted over her placemat for a tiny bite of her pie.

Encouraged, I said, “Your wedding shower’s tomorrow night at Betty’s, isn’t it, Mama? Be a shame to let all Betty’s preparations and those nice gifts go to waste.”

She regarded her left hand under the kitchen light. “I suppose I’d have to give Sal back his ring, too.”

Maddie added, “Not to mention, the deposits you’ll lose, canceling at this point.”

I heard Marty’s sigh of relief when Mama slipped the plate to the center of her placemat and really started in on the pie. She had it about half-gone when Teensy gave a yelp and skittered out from under the kitchen table toward the front door.

“Is that barbecue I smell?” a man’s deep voice boomed over Teensy’s barking. “Y’all better have saved me a plate.”

Our cousin Henry made his way into the kitchen, Mama’s Pomeranian yapping at his heels. Teensy did a few revolutions around Henry’s ankles, the pitch of his barking climbing higher each time he went airborne.

“Aunt Rosalee, I love you to death, but if you don’t silence that little varmint, I’m going to marinate him in sauce and stick him on a barbecue spit.”

Mama gasped, snatching Teensy off the floor and clutching him to her chest.

“You wouldn’t!” she said.

“Oh, I would,” Henry answered, but his grin belied the threat.

As Henry took a seat, I put a quarter-rack of ribs on a plate, and then doused the meat in warmed barbecue sauce. When I handed it to him, he licked his lips. “You got any cornbread? And how ’bout some baked beans?”

Maddie harrumphed. “You’d think an uninvited guest would be grateful for what he’s served.”

“Hush, Maddie.” Mama slapped her on the wrist. “You know Henry’s never a guest in this home. Henry’s family.”

As Mama got up to fetch his favorite sweet tea from the refrigerator, Henry leaned around her back and stuck out his tongue at Maddie. She balled up a paper towel and tossed it at him. It bounced off Henry’s forehead and hit Teensy, asleep on the floor.