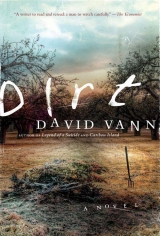

Текст книги "Dirt"

Автор книги: David Vann

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter 3

When Galen woke it was dark. The house silent. The time of peace. The way he wished the world could be. No people.

He had to shake his arm to get it to wake up. He flushed the toilet and brushed his teeth. Then he walked barefoot down the stairs, stepping as softly as possible, trying to walk with no weight. His body lifted in the air, gravity gone. This world a dream, the house made of memory. His mother as a child walking these same steps.

Out through the pantry, he walked beneath the enormous leaves of the fig tree, could smell its fruit, let his jeans and underwear and shirt slip to the ground, stood naked. The moon nearly full, and as he stepped around the farm shed into the walnut orchard, he saw the array of bones. Long rows of white trunks and branches all turned to bone in this light. Every branch hollow and too large, luminous. The leaves as shadows too insubstantial to cover.

Galen ran as he had read in the Carlos Castaneda books, let his bare feet find their way in the night, their own path, closed his eyes and held his arms out to the sides, palms up. The clods of dirt crumbling beneath his feet, rocks hard, small branches, leaves. All of it hurt and made him slow down, but he wanted to be lifted free. He wanted to drift over the ground without sound or feel, his feet held just above the surface by a kind of magnetism. Instead, his feet sank deep into furrows, stumbled and jolted, and he never knew what was coming next. He opened his eyes and slowed to a walk, put his arms down.

The moon the brightest of bones. Dark patches forming the open mouth of a snake, a small man sitting below, meditating. Always the same moon. It never revolved, never changed. Always this snake head and small man etched on a disc of bone.

The trees arrayed in obedience to the moon, lined up, reaching upward. Even the furrows responding to the pull. All of the earth extending, trying to close the gap. The air so thin, what was keeping the earth and moon apart?

Galen sat cross-legged, his lower back braced by a furrow, and stared up into the moon. His palms open on his knees. Long exhale, and breathe in deep. Exhale again. No thought, only this shining disc, this mirror.

But then he was thinking of his cousin, of the inside of her thigh, of her lips, of her foot pressed against his crotch. Samsara always there, always intruding. But perhaps it could be used. Perhaps it could provide some power.

Galen rose and put his hand on his boner. He stroked it a bit and then tried to run like that down the furrow, stroking with his right hand, his left hand held outward to the side, palm upward, a meditative pose, his eyes closed. He tried to let his legs guide him, tried to let the boner guide him, lift him above the furrows toward the moon. And his feet did feel lighter. He was gaining speed, the dirt falling away farther below, the air gaining a presence, and maybe that was the key. Not some sort of magnetism from the earth but a pulling from the air itself. The air was the medium, not the earth.

He tried to leave his body, tried to place his consciousness outside, to see himself from far away. White bone-legs running, like the tree trunks come alive.

But his breath was ragged, holding him to the world, pinning him here when he wanted to lift free. Tall weeds ripping at him, lashing him, a snag between his toes and he almost went down. He had to open his eyes and jog to the side to get around the worst patch. And this was the problem. Always an interruption. Whenever he was getting close to something.

So he stopped. Stopped running, stopped stroking. He tried to never come, because he’d read that a man lost his power when he came. But he really wanted to come. And he was tired of just his hand.

Galen lay down in the hollow between two furrows, curled on his side. Breathing heavily, wet with sweat, the air cool now on his skin. His forehead in the dirt. The world only an illusion. This orchard, the long rows of trees, only a psychic space to hold the illusion of self and memory. His grandfather giving him rides on the old green tractor, the putting sound of the engine. His grandfather’s Panama hat, brown shirt, smell of wine on his breath, Riesling. The feel of the tractor tugging forward, the lurch as the front wheels crossed over a furrow. All of that a training to feel the margins of things, the slipping, none of it real. The only problem was how to slip now beyond the edges of the dream. The dirt really felt like dirt.

Galen woke many times in the night, shivering. The moon a traveler, crabbing sideways through the stars. Galen on the surface of the earth. The planet not to be believed, spinning at thousands of miles per hour. There should be some sound to that if it were true. Some thrumming or vibration. But the dirt was soundless, and it felt too light, as if the earth’s crust were only a few feet deep. What Galen wanted was for the crust to crack so that he could fall through, fall thousands of miles flipping through empty space toward the center of gravity, accelerating, and then fall past the center toward the crust on the other side and feel himself slowing as gravity took hold. Until he’d reach the underside of the other side of the world and touch it lightly with his fingertips, then fall backward again. His feet would never touch ground, and that would be good.

Galen was so cold his teeth were chattering. But he didn’t get up. He fell back into sleep over and over, and the night was an endless thing. Each night a lifetime, including the wait for the end.

And when the end came, finally, when the sky lightened, the black become blue, Galen was not yet ready. Too quickly the air would bake, the earth would bake, and the day would repeat itself. There’d be tea with his mother and the visit with his grandmother and the visit from his aunt and cousin. Galen didn’t feel he could do it again.

He had to pee so badly he finally rose, sent an arc of piss toward a tree, then hooked his thumbs under his armpits and crowed a cockadoodledoo loud into the dawn. He strutted around naked, flapping his arms, warming up, calling in the day. His stomach an empty cavern, a pit shrinking him from the center. But he kept strutting, broke into a low run through the trees, then over to the main house. Stood beneath his mother’s window, crowed as loudly as he could and stomped his feet in the grass.

Damn it, Galen, he finally heard. I’m up now, and you know I won’t be able to fall back asleep.

Galen felt a smile, the real thing, happen across his face, his cheeks pulling themselves up. No stunted thing, his face not broken. He stopped crowing, walked over to grab his clothes from under the fig tree, and went in through the pantry. Quiet up the steps to his room, and he closed the door, took a shower to be clean finally, then buried himself under the covers, a warm nest, and fell deeply into sleep.

Chapter 4

Galen woke with Jennifer’s panties just a few inches from his face, thighs on either side of his head.

Good morning, cousin, she said. It’s a sin, you know, to peek at your cousin. But you’re always peeking. So I thought I’d give you a good, close look.

Blue silk, a different shade than the blue cotton yesterday. More tightly fitting. He could feel the heat. He tried to smell her, but she smelled only like soap.

He was afraid to say anything. He didn’t want this to end.

The twenty-two-year-old virgin, she said. This is the closest you’ve ever been, isn’t it?

Yeah, he said.

Why is that?

I don’t know. Just not very popular, I guess.

And a mama’s boy. You never leave this house.

People don’t value the spiritual enough.

You mean freaks don’t get laid. You can jack off. You can jack off while you look at me.

So he reached down and began pulling, squeezing tight, enjoying the ache of it.

I’m going to turn around, she said. So I can watch.

She stood up on the bed, which tilted like an ocean, and came back down facing the other way. She pulled away the blanket and sheet so he was exposed. He pulled harder. This view he’d never had before. The backs of her thighs and ass, so perfectly shaped, beautifully cupped, and the hollow and curve toward the front. The edges of her panties against soft creamy skin.

Can you pull your panties to the side? he asked. I wanna see.

No, she said. Not yet. You only get the panties for now.

Not yet, he said.

Why would you even want it? I thought you wanted the spiritual.

Galen’s dick was harder than it had ever been. He stroked more slowly to prolong this, and he could see she was getting wet, the silk darker in the center.

You’re getting wet, he said.

Yeah, she said. I like this. I like watching. I want you to come now.

So he sped up his hand and arched his hips, feeling every part of him drawn tight, and then he came and his neck pushed back and he shook with the pleasure. He opened his eyes again, her panties dark and wet above him, and he wanted her in his mouth. Please, he said. Let me see, or let me just lick.

Jennifer stood up on the bed, stepped down carefully onto the floor in her bare feet. No, she said. But that was fun. I like that. It’s always nice to spend time with family.

Galen laughed. It felt good to laugh, and he tried to add the little yelps again.

You’re a freak, she said. I’m leaving. But she was smiling, and Galen had never felt so good. When she was gone, he just lay there and smiled and stared up at the ceiling.

Then his mother was knocking at the door. Get up, she said. We’re having a quick lunch, and after that we’re working on the walnuts.

Galen had forgotten about the walnuts.

September, he yelled. The harvest isn’t until September. But she was already back downstairs.

It was only the end of July, but his mother would make them put out all the drying racks to inspect.

So Galen rose and cleaned up, then looked around for green clothing. He would dress as a green, unripe walnut. He had a green sweater and green rubber boots. What he was missing were green pants. But in the hallway closet, in the stacks that smelled of mothballs, he found two green towels. He doubled old belts around his thighs to cinch the towels into place, then pulled on the green boots.

Galen walked carefully down the stairs, and he felt like some old knight heading into battle. He’d carry a giant cucumber for a sword, or a spear of asparagus.

Mother, he said as he entered the dining room. I am Green Walnut, and I am reporting for duty.

Galen’s aunt Helen shrieked with laughter, and Jennifer snorted her milk onto her plate. But Galen’s mother continued cutting the crusts off her baloney sandwich. Fine, she said. Have some lunch, Green Walnut.

I hope my unripeness doth not offend, he said.

His mother quartered her sandwich diagonally and picked up one triangle. Today is a special day for me, she said. It was this time each year that Mom and Dad would put out the drying racks to inspect them. We’d start earlier, of course, at first daylight, when the air was still cool. And we’d work quietly. I’d feel the day heat up, and by lunchtime it was wonderful to stop and sit in the shade under the fig tree and have lemonade.

And don’t forget the wine, Helen said. The wine started in those early hours, too.

We’d drink lemonade, Galen’s mother said. And we’d have sandwiches, cut like this, and we’d be a family.

Until the bickering would start, Helen said. I’m not sure where you’re fitting in the bickering.

Stop, Galen’s mother said. Just stop. Why can’t you remember the good moments?

Gosh, I don’t know. Maybe because I wasn’t the one prancing around being cute? Maybe because I was older and knew what was going on?

That’s not fair.

Wake up, little Suzie-Q.

Galen poured himself a glass of lemonade and then considered the food options. Baloney and ham in plastic packets, American cheese also in plastic, saltine crackers in plastic, sliced bread in plastic. I think I’ll have a plastic sandwich, Galen said.

Mom and Dad had their problems, but what you don’t seem to understand is that we were lucky here, living in this place, working on the walnut harvest together.

Dad used to beat Mom. He’d beat her right in this dining room, and in the kitchen, and upstairs in their bedroom. What part of that are you not understanding?

He never beat her.

Oh, for chrissakes.

Galen didn’t want bread and mustard, which was one option, so he decided to go for the crackers instead. He grabbed a handful of saltines and crumbled them into his half-full glass of lemonade. He used a fork to submerge the pieces of cracker and then he drank his lemonade while shoveling with the fork. Salty and sweet and not really all that bad.

His mother was still working on her sandwich, and there seemed to be plenty of time, so he fixed another glass. A bit heavier on the crackers this time, pulpier, more substantial. Fitting in a good meal before a day’s work.

When his mother had finished, she rose to take her plate to the kitchen. She returned to the dining room and looked at them all, sitting there. For a moment, Galen felt bad. Felt guilty for dressing up like this and destroying her special day. She looked hurt, and he didn’t like seeing that. Not really.

I’m going to start on the racks, she said. If any of you want to join me, you may. She had curled her hair. Long brown waves. And she was wearing makeup. Galen wondered if she had planned this for the special day, or if it had happened only because she was up early from his crowing.

And then she was gone. He realized he was standing. Green Walnut must make up for everything, he said. Green Walnut has been very bad.

Hallelujah, Brother, Jennifer said.

She deserves it, his aunt said. You’re the perfect curse for her.

But Galen ignored them, sallied forth out the pantry door and walked stiffly to the farm shed, trying not to lose the towels, same path he had taken last night into the orchard.

He found the large bay door slid open. The green tractor, slim front tires, narrow ventilated snout. A thing of the past. But he tried not to be distracted. Stepped into the dark half of the shed, where his mother was hidden deep in the piles of racks.

Just carry them out? he asked. Smell of dust and mildew, smell of walnut husks. Smell of his childhood. If he closed his eyes, he could go right back, and no doubt this was what his mother was doing now. We have the same childhood, he said. Because of the smell of this room.

Not the same, she said. You have no idea. You can’t imagine what it was like.

Fine, he said. Your specialness can’t be touched. So where do you want the racks?

His eyes were adjusting and he could see them more clearly now, square wooden frames with mesh screens. Stacked like bricks, making a wall.

I’m only telling you the truth, she said. It was a different time. I’m not the enemy.

He clenched his teeth and made a growling sound and shook his arms. It was just what he felt.

You won’t be able to do that to anyone else, she said. You treat me worse than you’d be allowed to treat any other person. I’m just about at the end of my patience.

Your patience? Galen asked. He grabbed a rack and stepped around the tractor, into the bright hot sun. His blood pounding. He walked twenty yards to the staging area and set the rack down in the dirt. He got on his knees and grabbed big dirt clods like the earth’s own walnuts and set them in the rack. Dark crusted shapes already drier than the sun itself, and these would put the rack to good use.

The towels on his legs were too difficult to keep in place, so he let them fall. Bare legs and underwear, a green sweater and green boots. He passed her on the way back to the shed, kept his eyes on the ground. I haven’t done anything to you, he hissed.

Like jousting, he thought. Tilting at each other, only a brief moment of contact. He stepped into darkness, grabbed a rack and set it on the ground, grabbed another and stacked it, grabbed another. They were heavy, made of wood, and he wasn’t sure he could carry three at once, but he picked them up, his back washing out a bit, then recovering. He stumbled outside, his cheek pressed against wood, and tottered his way to the staging area.

His mother was removing all the dirt clods from the rack he had placed. Those aren’t dry yet, he said. But she didn’t say anything in return. Just knelt there in the dirt in her work pants and one of her father’s old work shirts, sun hat and gloves, removing clods.

He set down the stack of three racks and headed back for more. He grabbed another three, brought them out into the sun. Then he had an idea.

He set all six racks next to each other in a long row, and he lay down on the racks, careful not to punch through any of the mesh screens. He made sure his butt and head and ankles were supported on the wooden edges. Another edge made a crease in his back.

Why do you do this to me? his mother asked. Her voice as quiet as a whisper.

Green Walnut needs to be dried, he said. And these are the drying racks. He tried to keep his eyes open, staring up into the midday sun. He was roasting in his sweater, and his bare legs and face would burn. He would stay out here the rest of the day. The wooden edges so hard across his back and neck he didn’t know how he’d last even the next five minutes, but he was determined. It would be a meditation, and who knew what might lie on the other side.

All I’ve sacrificed for you for more than twenty years, his mother said in a low voice. Get up before Helen and Jennifer see you.

Galen could hear his aunt and cousin talking at the shed, coming this way. Why does it matter if they see? he asked. I’m just curious. I don’t see why it would matter.

Just get up now.

No, he said. I’m staying here like this all day.

The sun so bright Galen couldn’t see his mother, couldn’t judge what might come next. But she only walked away.

He tried to relax into the hard wood, tried to let his flesh and bones find a soft way of fitting to the wood. The edges cutting into his butt were making his legs numb, and the edge across his back made breathing more difficult, but the one at his neck was the most urgent. He tried to exhale, stare at the sun, forget this existence, find something else.

You already look like jerky, his aunt said.

His thighs are white, Jennifer said.

True, his aunt said. And I guess they should match his face and neck.

Galen dizzy and blind, his eyes filled with flashes and spots, but he could hear the work on every side, a pointless task. The racks didn’t need to be cleaned or oiled or maintained in any way, unless a screen was broken. But none of them knew how to repair a screen. If one was broken, they’d simply put that rack aside, in the pile directly behind the tractor, and not use it. So what was happening today was that they were taking all of the racks out of the shed and then putting them away again.

We’re just going through the motions, Galen said.

What’s that? his aunt asked.

Our whole lives, Galen said, just reenactments of a past that didn’t really exist.

The past existed, his mother said. You just weren’t there. You think anything that’s not about you isn’t real.

What about my father? Galen asked. Can you prove he’s real? Can you narrow it down to the two or three men who are most likely, at least?

No answer to that. Never an answer to that. Only the sounds of their shoes in the dirt, the sounds of racks being picked up now, returned to the shed.

I have some other questions too, Galen said. I’m not finished.

But no one was listening to him, it seemed, and his back was so destroyed by now it hurt too much to speak. So he closed his eyes, saw bright pink with white tracers and solar flares, a world endlessly varied and explosive. His body spinning in the light. Face and thighs cooking, a stinging sensation. But he would stay here, he would see this out.

Pain itself an interesting meditation. On the surface, always frightening, and you wanted to run. Very hard not to move, very difficult, at least at first, to do nothing. Pain induced panic. But beneath the surface, the pain was a heavier thing, dull and uncomplicated. It could become a reliable focal point, a thing present and unshifting, better even than breath. And the great thing about these racks was that they distributed the pain throughout his body. He was afraid his neck and back might actually be damaged, and that was a part of pain, too, the fear of maiming, of losing permanently some part of the body. Even an insect didn’t want that. No one wanted to lose a leg or an arm or the use of their back, and so as we approached this moment, we approached a kind of universal, and if we could look through that, and detach ourselves, we might see the void beyond the universals, some region of truth.

Stop thinking, Galen told himself. The thinking was a cheat, robbing him of the direct experience. And it’s also bullshit, he said aloud. It’s all bullshit. I’m just lying on a rack, and that’s all.

His mother and aunt and cousin having high tea now. All sounds of their movement gone. Only the sounds of flies and bees on flight paths nearby, the dry landings of grasshoppers, an occasional car passing. The world in its immensity and such disappointing nothingness. Galen rolled over, off the racks, into the dirt. Just like that. No decision, just rolled over, and now it was gone, the entire experience, all wasted, and he was in the dirt again. Nothing learned, nothing gained.