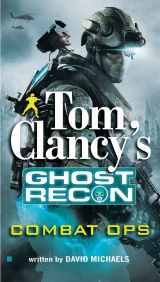

Текст книги "Ghost recon : Combat ops"

Автор книги: David Michaels

Жанр:

Боевая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

CO MB AT O P S

19

and was muttering something, even as a second guy

rounded the corner.

My two rounds missed him and chewed into the

stone. He ducked back round the corner. I blamed my

error on the shadows and not my dependence on the

Cross-Com’s targeting system. As I rationalized away

the failure, a grenade thumped across the floor, rolled

toward me, and bounced off the leg of the guy I had just

killed.

Ramirez, who’d seen the grenade, too, lifted his

voice, but I was already on it, seizing the metal bomb

and lobbing it back up the hallway, only two seconds

before it exploded. Ramirez and I were just turning our

backs to the doorway when the debris cloud showered

us, pieces of stone stinging our arms and legs and

thumping off the Dragon Skin torso armor beneath our

utilities.

We turned back for the hall.

And my breath vanished at the sound of a second

metallic thump. This grenade hit the dead guy’s boot

and rolled once more directly into the room.

Ramirez was on it like a New York Yankees shortstop.

He scooped up the grenade, whirled toward the open

window, and fired it back outside. We rolled once more

as the explosion resounded and the walls shifted and

cracked.

I’d had enough of that and let my rifle lead me back

into the hallway. I charged forward and found the

remaining guy withdrawing yet a third grenade from an

old leather pouch. He looked up, dropped his jaw, and

20

GH OS T RE C O N

shuddered as my salvo made him appear as though he’d

grabbed a live wire. He fell back onto his side.

I stood over him, fighting for breath, angry that

they’d kept coming at us, wondering if he’d been one of

the guys who’d perpetrated the acts we imagined had

gone on in that room. I returned to Ramirez, who’d

gone over to the pool table. That’s right, a pool table.

But they hadn’t been playing pool.

A girl no more than thirteen or fourteen lay nude and

seemingly crucified across the table, arms and legs bound

by heavy cord to the table’s legs. Ramirez was checking

for a carotid pulse. He glanced back at me and whis-

pered, “She looks drugged, but she’s still alive.”

I tugged free my bowie knife from its calf sheath and,

gritting my teeth, cursed and cut free the cords. Then I

ran back and ripped the shirt off the dead guy just out-

side the door. Neither of us said a word until Ramirez

lifted her over his shoulder in a fireman’s carry, and I

draped the shirt over her nude body.

I just shook my head and led the way back out.

In the courtyard, I swept the corners, remained wary

of the rooftops, and reached out with all of my senses,

guiding us back toward the gate without the help of the

Cross-Com. Women were wailing somewhere behind

one of the buildings, and the stench of gunpowder had

thickened even more on the breeze.

Gunfire sounded from somewhere behind me, and

the next thing I knew I was lying flat on my face. Before

Ramirez could turn, the girl still draped over his shoul-

der, an insurgent rushed from the house.

CO MB AT O P S

21

The guy took two, maybe three more steps before

thunder echoed from the mountain overlooking the

town. I gaped as part of the man’s head exploded and

arced across the yard. The rest of him collapsed in a dust

cloud.

Treehorn was earning his place on the team.

“Captain, you all right?” cried Ramirez.

I sat up. “I should’ve seen that guy. Damn it.”

“No way. He was tucked in good.” Ramirez crossed

around to view my back. “He got you, but the armor

took it good. Nice . . .”

“And off we go,” I said with a groan as I dragged

myself to my feet. I remembered the Cypher drone,

darted over to it, and tucked the shattered UFO under

my arm.

We hustled around the main perimeter wall, these

barriers common in many of the towns and not unlike

the medieval curtain walls that helped protect a castle.

It took another ten minutes before we reached the

edge of the town, then made our dash up a dirt road ris-

ing up through the talus and scree and into the canyons.

The gunfire had kept most of the locals inside, and what

Taliban were left had fled because they never knew how

many more infidels were coming.

We met up with Marcus Brown and Alex Nolan some

ten minutes after that, and Ramirez handed off the girl

to Nolan, who immediately dug into his medic’s kit to

see if he could get her to regain consciousness.

“Any sign of Zahed?” I asked Brown.

Despite being a rich kid from Chicago, he spoke and

22

GH OS T RE C O N

acted like a hardcore seasoned grunt. “Nah, nothing.

What the hell happened?”

I wished I could give the big guy a definitive answer.

“Our boy got tipped off. And someone took out our

Cross-Com and the drone. Somehow. I can’t believe it

was them.” I handed the drone to him, and he stowed it

in his backpack.

“So who did this?” he asked. “Our own people? Why?”

I just shook my head.

Brown’s dark face screwed up into a deeper knot. He

cursed. I seconded his curse. Ramirez joined the four-

letter-word fest.

Three more operators—Matt Beasley, Bo Jenkins,

and John Hume—arrived a few minutes after with three

prisoners in tow, their hands bound behind their backs

with zipper cuffs.

I nodded appreciatively. “Nice work, gentlemen.”

“Yeah, but no big fish, sir,” said Hume. “Just guppies.”

“I hear that.”

Treehorn ascended from his sniper’s perch and joined

us, fully out of breath. “Guess I blew the whistle a little

too soon,” he admitted.

I was about to say something, but my frustration was

already working its way into my fists. I walked over,

grabbed the nearest Taliban guy by the throat, and, in

Pashto, asked him what had happened to Zahed.

His eyes bulged, and his foul breath came at me from

between rows of broken and blackening teeth.

I shoved him back toward his buddies, then pointed

at the girl. “Did you do this?” I was speaking in English,

CO MB AT O P S

23

but I was so pissed I hadn’t realized that. I shouted

again.

One guy threw up his hands and said in Pashto, “We

do not do that. I don’t think Zahed does that, either.

We don’t know about that.”

“Yeah, right,” snapped Ramirez.

Nolan got the girl to come around, and she began

crying. Ramirez went over and tried to calm her down;

he got her name, and we learned that she was, as we’d

already suspected, from Senjaray, the town on the other

side of the mountains from which we operated. We had

conventional radio, but even that had been fried, and

Hume suspected that some kind of pulse or radio wave

had been used to disrupt our electronics.

We hiked over the mountain, keeping close guard on

the prisoners and taking turns carrying the girl. We

eventually reached our HMMW V, which we’d hidden in

a canyon. The radio onboard the Hummer still worked,

so we called back to Forward Operating Base Eisen-

hower and had them send out another Hummer to

bridge the eleven-kilometer gap. We set up a perimeter

and waited.

“You know, this place makes China look good,” said

Jenkins, who lay on his stomach across from me, his nor-

mally hard and determined expression now long with

exhaustion. “Those were the good old days. That was a

straight-up mission. Pretty good intel. And good sup-

port from higher. That’s all I ask.”

“I don’t know, Bo, I think those days are gone,” I

said. “No matter how good we think our intel is, we can

24

GH OS T RE C O N

wind up like this. And I know it’s discouraging. But I’ll

do what I can to find out what happened.”

“Thanks.”

No matter how careful we’d been in leaving our FOB,

no matter how secretive we’d kept the mission, all it took

was one observer to radio ahead to Zahed that we were

coming. We’d taken all the precautions. Or at least we’d

thought we had.

And at that moment, I was beginning to wonder

about our “find, fix, and finish the enemy” mantra. I

still wasn’t buying into the whole COIN ideology (let’s

help the locals and turn them into spies) because I fig-

ured they’d always turn on us no matter how many

canals we built. But I wondered how we were supposed

to gather actionable intelligence without help from the

inside—without members of the Taliban itself turning

on each other . . . because in the end, everyone knew we

Americans weren’t staying forever, so all parties were

trying to exploit us before we left.

The second truck arrived, and we loaded everyone on

board and took off for the drive across the desert. My

hackles rose as I imagined the Taliban peering at us from

the mountains behind. My thoughts were already leap-

ing ahead to solve the security breach and tech issues.

Treehorn, who was at the wheel, began having a con-

versation with himself, offering congratulations for his

fine marksmanship. After a few minutes of that, I inter-

rupted him. “All right, good shooting. Is that what you

want to hear?”

“Hell, Captain, it’s something. I got the feeling this

CO MB AT O P S

25

whole op will go round and round, and we won’t get off

the roller coaster till higher tells us.”

I considered myself an optimist, the never-say-quit

guy. I’d been taught that from the beginning. Hell, I’d

been a team sergeant on an operation in the Philippines

and lost nearly my entire ODA unit. My best friend

flipped out. But even then, I never quit. Never allowed

myself to get discouraged because the setbacks weren’t

failures—they were battle scars that made me stronger. I

had such a scar on my chest, and it used to remind me

that there was a larger purpose to my life and that quit-

ting and becoming depressed was too selfish. I’d be let-

ting everyone down. I had to go on.

If you join the military for yourself, then you’re setting

yourself up for failure. Kennedy had it right: Ask what

you can do for your country. I’ve seen many guys join

“for college” or “to see the world” or “to learn a trade.”

Their hearts are not in it, and they never achieve what

they could. Perhaps I’m too biased, but in the beginning,

there was an ideal, an image of America that I kept in my

head, and it reminded me of why I was there.

Kristen Fitzgerald, standing among acres of lush

farmland, her strawberry-blond hair tugged by the wind.

She smiles at me, even says, “This is why.”

Pretty cliché, huh? Makes it sound like I do it all for a

girl. But she represented that ideal. A high school sweet-

heart who told me she’d always wait, that she was like

me, that we were not born to live ordinary lives.

My ideal was not some jingoistic military recruiting

commercial or some glamorous Hollywood version of

26

GH OS T RE C O N

war. I didn’t join because I wanted to “get some.” I

wanted to protect my country and help people. That

made me feel good, made me feel worth something.

And as the years went on, and I got promoted and was

told how good I was, I decided to share what I knew. I

loved teaching at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare

Center at Fort Bragg. I couldn’t think of a more reward-

ing part of my military career.

In fact, that was where I met Captain Simon Harruck,

who’d been a fellow trainer despite his youth and who was

now commander of Delta Company, 1st Battalion—120

soldiers charged with providing security for Senjaray and

conducting counterinsurgency operations.

I knew that when we got back, Harruck would try

to cheer me up. He was indeed ten years my junior,

and when I looked at him, oh, how I saw myself back in

those days.

But as we both knew, the ’Stan was unforgiving, with

its oppressive heat and sand that got into everything,

even your soul. I threw my head back on the seat and

trusted Treehorn to take us home, headlights out,

guided by his night-vision goggles.

By the time we arrived at the FOB, Harruck was

already standing outside the small Quonset hut that

housed the company’s offices, and the expression on his

face was sympathetic. “Well, we got three we can talk to,

right?”

I returned a sour look and marched past him, into

the hut.

THREE

The three prisoners were taken to a holding room. The

CIA was sending a chopper down to transfer them to

FOB Chapman in Khost, where some big shot from

Kabul would come in to interrogate them. FOB Chap-

man was the CIA outpost where seven agents were killed

years ago. I knew this time the bad guys would be strip-

searched, x-rayed, and then have their every orifice and

cavity probed.

Didn’t matter, though. I didn’t think they knew

much. Zahed wasn’t fool enough to allow underlings to

know his plans or whereabouts.

The girl was taken to our small hospital, and we

could only speculate on what would happen to her after

that. She was damaged goods, a disgrace and dishonor

28

GH OS T RE C O N

to her family, and they would, I knew, not want her

back. A terrible thing, to be sure. She might be trans-

ported to one of the local orphanages and/or assisted by

one of the dozens of aid groups in the country. She

might even be arrested. I couldn’t think about her any-

more, and I’d made it a point notto learn her name. Her

plight fueled my hatred for the Taliban andthe local

Afghans. No one cared about her. No one . . .

I sent the rest of my team back to quarters. We’d

debrief in the morning. I sat around Harruck’s desk, and

he offered me a quick and covert shot of cheap scotch,

saying we’d turn ourselves in later and receive our letters

of reprimand.

Harruck was a dark-haired, blue-eyed poster boy

who made you wonder why he’d joined the military. He

resembled a corporate type who played golf on the week-

ends with clients. He was taking graduate courses online,

trying to earn his master’s, and he kept on retainer two

or three girlfriends back home in San Diego. Because he

was so articulate and so damned smart, he’d been

recruited to teach at the JFK School, and when he wasn’t

overseas, he participated in our four-week-long uncon-

ventional warfare exercise, Robin Sage. The first time I

met him, I was immediately impressed by his knowledge

of our tactics, techniques, and procedures. His candor

and sense of humor invited you into a conversation.

Once there, you realized, Holy crap, this guy is for real:

talented, intelligent, and handsome. If you weren’t jeal-

ous and didn’t hate him immediately, you wanted him

on your team.

CO MB AT O P S

29

But those attributes did not make him famous around

the Ghosts, no. He was, as far as I knew, the only Army

officer who’d been offered his own Ghost unit and had

turned down the offer.

Let me repeat that.

He’d become a Special Forces officer, had led an ODA

team for a while, but when asked to join the Ghosts,

he’d said no—and had even gone so far as to leave Spe-

cial Forces and return to the regular Army to become a

company commander.

We called it temporary insanity. Or alcoholism. Or

some said cowardice: Pretty boy didn’t want to get a

scratch on his smooth cheek.

I’d never asked him why he’d done this. I didn’t want

to pry, but I was also afraid of the answer.

“I don’t know how much help you want with your

gear,” Harruck said after we finished our drinks. “All

your toys are classified, but I’ve got some guys that’ll

take a look if you want.”

“That’s all right. I’ll have to ship a few units back and

see what they say. Meanwhile, we’ll have to wait till they

drop in replacements.”

“Any thoughts?”

“Taliban bought EMP weapons from China,” I said

through a dark chuckle. “It’d make sense. We’re run-

ning a war on their money now. Wouldn’t they do every-

thing they can to keep us spending? It worked when we

did it to the Russians.”

“I hear that.”

“I’ve still got a half dozen more drones I can send

30

GH OS T RE C O N

up—if I can get some Cross-Coms. The disruption’s

localized, so we’ll find out what they’re using. I’m curi-

ous to see who they’re playing with now.”

“What if it’s us?”

I snorted. “NSA? CIA? You think they’re in bed with

Zahed? Well, if that’s true—”

“You sound tense.”

“I’m not good with setbacks, you know that. I fig-

ured we’d capture this guy tonight and get out.”

Harruck wriggled his brows. “Yeah, I mean he’s a fat

bastard. He can’t even run.”

I smiled. Barely.

“You need to relax, Scott. You’re only here a few days.

And the last time you were here, that didn’t last long,

either. You’ve been lucky. It’s eight months for me now.

Damn, eight months . . .”

“Still smiling?”

“To be honest with you—no.”

I shifted to the edge of my seat. “Are you kidding me?”

“This might sound a little hokey, but you know what?

I came here to build a legacy.”

“A legacy?”

“Scott, you wouldn’t believe the pressure they’ve put

on me. They think this whole war can be won if we

secure Kandahar.”

“I hear you.”

“They’re calling it the center of gravity for the insur-

gency. That’s some serious rhetoric. But I can’t get the

support I need. It’s all halfhearted. I’m going to walk

out of here having done . . . nothing.”

CO MB AT O P S

31

“That’s not true.”

Harruck leaned back in his chair and pillowed his

head in his hands. “I know what these people need. I

know what my mission is. But I can’t do it alone.”

I averted my gaze. “Can I ask you something? Why

did you do this to yourself?”

“What do you mean?”

I took a moment, stared at my empty glass.

“Another one?” he asked.

“No. Um, Simon, this isn’t any of my business, but

you could’ve been a Ghost.”

“Aw, that’s old news. Don’t make me say something

I’ll regret.”

I smiled weakly. “Me, too.”

I’d had no idea that Harruck was exercising tremen-

dous reserve in that meeting, when, in fact, he’d proba-

bly wanted to leap out of his chair and throttle me.

Forward Operating Base Eisenhower lay on the north-

west side of Senjaray. It was a rather sad-looking collec-

tion of Quonset huts and small, prefabricated buildings

walled in by concrete and concertina wire. The main

gate rose behind a meager guardhouse manned by two

sentries, with more guards strung out along the perim-

eter. The usual machine gun emplacements along with a

minefield on the southern approach helped give the

Taliban pause. The juxtaposition between the ancient

mud-brick town blending organically into the landscape

and our rather crude complex was striking. We were

32

GH OS T RE C O N

foreigners making a modern and synthetic attempt to

assimilate.

Harruck knew he’d never get his job done by hiding

behind the walls of the FOB, so nearly every day he went

into the town to communicate with the people via

TCAF interviews (we pronounced it “T-caff”), which

stood for Tactical Conflict Assessment Framework. Har-

ruck’s patrols were required to ask certain questions:

What’s going on here? Do you have any problems? What

can we get for you?

And he’d get the same answers over and over again:

We need a new well, we want you to rebuild and open the

school. We need a police station, more canals. And can you

get us some electricity?The diesel power plant in Kanda-

har serviced about nine thousand families, but nothing

had been provided for the towns like Senjaray.

The following week, Harruck’s patrols would ask the

very same questions, get the same answers, and nothing

would be done because Harruck couldn’t get what he

needed. The reasons for that were complex, varied, and

many.

Despite the cynicism creeping into his voice, I still

trusted that he’d fly the flag high and struggle valiantly

to complete his mission. He said that at any time the

tide could turn and assets could be reallocated to him.

We Ghosts didn’t have the luxury of leaving the base.

In fact, higher wanted us to protect our identities by

remaining in quarters when we weren’t conducting

night reconnaissance, so I told my boys we were ghosts

CO MB AT O P S

33

andvampires while in country, but that didn’t last very

long.

I finished up a quick conversation with General Keat-

ing via my satellite phone, and he gave me the usual:

“We need Zahed in custody, and we need him talking to

us about his connections to the north and the opium

trade. It’s up to you, Mitchell.”

It was always up to me, and I had a love-hate relation-

ship with that burden.

Keating’s trust in me was like a drug. Sometimes I

felt like he was grooming me for his own job. I’d already

turned down a promotion only because that would

mean less time in the field, and I thought I was still too

young to rotate to the rear. Scuttlebutt about the mili-

tary restructuring was rampant, with talk of a new Joint

Strike Force, and the general told me I needed to catch

the wave. But I believed I could make a greater differ-

ence in the field.

I guess, even after all these years, I was still pretty

naïve in that regard, probably because most of my mis-

sions had allowed me to turn the tide.

With the sun beating down on my neck with an

almost heavy-metal pulse, I headed toward my quarters.

Up ahead, Harruck was coming into the base, riding

shotgun in a Hummer. He waved to me as the truck

came under sudden and heavy gunfire.

Rounds ricocheted off the Hummer’s hood and

quarter panels as I dove to the dirt, and the two guys on

the fifties on the north side opened up on the foothills

34

GH OS T RE C O N

about a quarter kilometer away. But the fire wasn’t com-

ing from there, I realized. It was from inside the FOB.

Three insurgents had somehow gotten past the wall

and concertina wire and were firing from positions along

the south side of one Quonset hut, which I recalled housed

the mess hall.

Harruck and his men were climbing out of the Hum-

mer when one of the insurgents shifted away from the

hut and shouldered an RPG.

“Simon!” I hollered. “RPG! RPG!”

He and the two sergeants who’d been in the vehicle

bolted toward me as behind them the rocket struck the

Hummer and exploded, flames shooting into the sky,

the boom reverberating off the huts and other buildings,

whose doors were now swinging open, soldiers flooding

outside.

I had my sidearm and was already squeezing off

rounds at the RPG guy, but he slipped back behind the

hut. At that point, reflexes took over. I was on my feet,

catapulting across the yard. I rushed along the hut

between the mess hall and the insurgents, reached the

back, rounded the corner, and spotted all three of

them—at exactly the same moment the machine gun-

ners up in the nest did. I shot the closest guy, but only

got him in the shoulder before the machine gunner

shredded all three with one fluid sweep.

At that second, I remembered to breathe.

Up ahead came a faint click. Then the entire rear

third of the mess hall burst apart, pieces of the hut hur-

tling into the sky as though lifted by the smoke and

CO MB AT O P S

35

flames. The explosion knocked me onto my back, and

for a few seconds there was only the muffled screams

and the booming, over and over.

Something thudded onto my chest, and when I sat up,

I saw it was a piece of the roof and accompanying insula-

tion. And then it dawned on me that there’d been per-

sonnel in the mess, still coming out when the bomb had

gone off. Wincing, I got up, staggered forward.

A gaping hole had been torn in the side of the mess,

and at least a half dozen of Harruck’s people were lying

on the ground, torn to pieces by the explosion as they’d

been heading toward the door. Some had no faces, the

blast having shredded cheeks and foreheads, skin peeling

back and leaving only bone in its wake. I began cough-

ing, my eyes burning through the smoke, as Harruck

arrived with his sergeants.

“I’ll get my people out here to help!” I told him.

He nodded, gritted his teeth, and began cursing at

the top of his lungs. I’d never seen him lose it like that.

The facts were clear. We Ghosts had brought this on

the camp; the attack was payback for our raid the night

before. Innocent soldiers had died because of what we’d

done.

I felt the guilt, yes, but I never allowed it to eat at me.

We had orders. We had to deal with the consequences of

those orders. But seeing Harruck so cut up left me feel-

ing much more than I wanted. Maybe that was the first

sign.

My Ghosts were already outside our hut, all wearing

pakolsand shemaghson their heads and wrapped around

36

GH OS T RE C O N

their faces to conceal their identities. I ordered them out

to the perimeter to see what the hell was going on.

A roar and thundering collision out near the guard

gate stole my attention. A flatbed truck had just plowed

through the gatehouse and barreled onward to smash

through the galvanized steel gates.

The guards there had backed off and were riddling

the truck with rifle fire.

And it took Treehorn all of a second to shoulder his

rifle and send two rounds into the head of that driver.

But as if on cue, the truck itself exploded in a swelling

fireball that spread over the buildings and quarters beside

it, setting fire to the rooftops as more flaming debris

came in a hailstorm across the walkway between the huts.

We didn’t realize it then, but a hundred or more Tal-

iban had set up positions along the mountains, and once

they saw the truck explode, they set free a vicious wave

of fire that had all of us in the dirt and crawling for cover

as our machine gunners brought their barrels around . . .

and the rat-tat-tat commenced.

FOUR

Two more pickup trucks raced on past our FOB, cutting

across the desert and bouncing up and onto the gravel

road leading toward the town and the bazaar. Hundreds

of people were milling about that area, setting up shop

or making their morning purchases. If the Taliban

reached that area and cut loose into the crowds . . .

I shouted for the Ghosts to follow me, and we com-

mandeered two Hummers from the motor pool on the

east side of the base. A couple of mechanics volunteered

on the spot to be our drivers. We roared out past the

shattered gate, me riding shotgun, the others standing

in the flatbeds or leaning out the open windows, weap-

ons at the ready. I quickly wrapped a shemagharound

my face.

38

GH OS T RE C O N

Behind us, the fires still raged, and the machine guns

continued to crack and chatter.

Rounds ripped across the hood of our vehicle, and I

began to smell gasoline.

“We should pull over!” shouted the mechanic.

“No, get us behind those trucks!”

“I’ll try!”

About fifty meters ahead, the two pickups made a

sharp left and disappeared behind a row of homes.

The mechanic floored it, and my head lurched back as

we made the turn.

My imagination ran wild with images of civilians fall-

ing under our gunfire as we tried to stop these guys. I

could already hear the voices of my superiors shouting

about the public relations nightmare we’d created.

The second Hummer fell in behind us, and we charged

down the narrow dirt street, walled in on both sides by

the mud-brick dwellings and the rusting natural gas tanks

plopped out front. The familiar laundry lines spanned the

alleys and backyards, with clothes, as always, fluttering

like flags. Our tires began kicking up enough dust to

obscure the entire street in our wake, even as we pushed

through the dust clouds whipped up by the Taliban

trucks.

We still didn’t have replacement Cross-Coms, and all

I could do was call back to the other truck and tell them

we weren’t breaking off; we were going after these guys.

And yes, the threat of civilian casualties increased dra-

matically the farther we drove, but I wanted to believe

we could do this cleanly. I’d done it before.

CO MB AT O P S

39

Nolan, Brown, and Treehorn had already opened fire

on the rear Taliban truck, knocking out a tire and send-

ing one of the Taliban tumbling over the side with a

bullet in his neck. The rear truck suddenly broke off

from the first, making a hard left turn down another

dirt street.

I told the guys in our rear truck to follow him while

we kept up with the lead truck, whose driver steered for

the bazaar ahead, the road funneling into an even more

narrow passage.

Although I’d never been into the town, Harruck had

told me about the bazaar. You could find handmade

antique jewelry, oil lamps, Persian rugs, and tsarist-era

Russian bank notes displayed next to bootlegged DVDs

and knock-off Rolexes. There were also dozens of white-

bearded traders selling meat and produce. Some vendors

were part of an American-backed program that intro-

duced soldiers to Afghan culture and injected Ameri-

can dollars into the local economy. Although locals

bought, sold, and traded there, Harruck’s company actu-

ally pumped more money into the place than anyone else

because his soldiers purchased food to prepare on the

base and souvenirs to ship back home. The Taliban knew

that, too, which was why they’d come: maximum casual-

ties and demoralization.

We nearly ran over two kids riding old bikes, and the

mechanic was forced to swerve so hard that we took out

the awning post of a house on our left. The awning col-

lapsed behind us, and I cursed.

Suddenly, our Hummer coughed and died.

40

GH OS T RE C O N

My guys started hollering.

“We’re out of gas,” shouted the driver. “It all leaked

out!”

“Dismount! Let’s go!” I shouted to Nolan, Brown,

and Treehorn, then eyed the driver. “You stay here with

the vehicle. We’ll be back for you.”

The four of us sprinted down the block, reaching the

first set of stalls covered by crude awnings. The shop-

keepers had seen the pickup fly by and had retreated to

the backs of their shops.

The truck screeched to a stop at the next intersection,

about fifty meters ahead, and four Taliban jumped out.

I expected them to do one of two things:

Run into the crowd and draw us into a pursuit.

Or . . . take cover behind their truck and engage us in

a gunfight.

Instead, something entirely surreal happened, and all

I could do was shout to my men to hold fire.

The citizens of Senjaray rushed into the street, both

vendors and shoppers alike, and quickly formed a human

barricade around the four men and their truck.

Two of the vendors began shouting and waving their

fists at us, and from what I could discern, they were yell-

ing for us to go home.

As we drew closer, the crowd grew, and the four Tal-

iban were grinning smugly at us.

A man who looked liked a village elder, dressed all in

army-green robes and with a black turban and matching

vest, emerged from one of the shops and ambled toward

CO MB AT O P S

41

us, his beard dark but coiled with gray. Most of the

locals wore beat-up sandals, but his appeared brand-new.

In Pashto he said his name was Malik Kochai Kundi.

“I own most of the land here. I will not allow you to

hurt these men. Zahed has treated us well—much better

![Книга [Magazine 1966-07] - The Ghost Riders Affair автора Harry Whittington](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-07-the-ghost-riders-affair-199012.jpg)