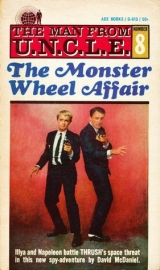

Текст книги "The Monster Wheel Affair"

Автор книги: David McDaniel

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

In another minute the highly volatile fuel had fallen safely from the jet and vaporized in the thin, cold air.

Illya was talking again. "Hello, unidentified station. If you're an aircraft carrier, we have visual contact. Shall we set down on your flight deck, or ditch? Over."

The answer to this was relatively unimportant. It would be nice to have the jet handy, and it would cost U.N.C.L.E. a fair sum to replace it, but the die had been cast when the ship had answered the distress call.

There was a pause of several seconds from the other station, then the voice said, "Can you handle a deck landing? If so, we'll have crash gear standing by for you. Over."

"Affirmative. Starting descent."

Illya replaced the microphone and gave the control wheel a gentle nudge. The little plane obediently began a descending spiral.

"He sounds like a nice guy," said Napoleon reflectively. "Almost a shame to pirate him. What say we don't make him walk the plank?"

"You're too soft-hearted to be a good pirate, Napoleon. Remember the cargo he's carrying and where it's going."

"All right, Captain Blood. But it's not his fault; he's only a tool of his government. In fact, I wouldn't be at all surprised if he's broken orders, either direct or implied, by saving our lives."

"Don't worry; when this is all over, he'll probably get a medal. We're at fifteen thousand feet—get ready with the engine fire."

"Ready."

"Then fire the nasty thing."

Napoleon twisted the red-knobbed lever and pushed it straight down. Almost at once a dull explosion sounded outside the left side of the plane, and the whole aircraft rocked violently. Illya fought with the control wheel for several seconds in a fierce attempt to keep from going into a tailspin, and cut the power to the starboard engine as soon as he had a hand free. Then he took a moment to glance out the window.

He smiled. "Beautiful," he said. "Just beautiful."

Napoleon could think of several things more beautiful. Outside the window their engine pod was a mass of roaring yellow and white flame which writhed along the surface of the wing, reaching for the almost-empty fuel tanks. Far away there was only a field of blue, alternating light and dark as the sky and the sea swept past. And the dark blue was getting closer at each pass.

Now it was showing texture, like a piece of fine cloth instead of glossy metal. And now the texture was expanding until the dancing specs of whitecaps whirled dizzily past as the jet continued to spiral downward. Illya was one of the few pilots in the world Napoleon would trust to do this to a plane he was in—it takes great control to appear to lose control completely, especially in front of the experts who were doubtlessly watching with critical and suspicious eyes from the deck of the Egyptian aircraft carrier below them.

Illya pulled out of the flat spin with a purposely clumsy falling-leaf maneuver, and threw them into a reverse spin for a few seconds with only a couple hundred feet of very thin air between them and the jagged surface of the sea. Then he managed to level off.

Only one engine was functioning, and it was on half power. The other still roared flame, and the plane appeared, even to Napoleon, who knew better, to be limping badly.

The carrier was dead ahead of them, and growing slowly. Illya pulled the wheel hard back, and the jet climbed to the edge of a stall before he let it off. The maneuver gained them another hundred feet, and a clearer view of the ship.

It was an old carrier, of a type nearly made extinct by the attack on Pearl Harbor. The flight deck was short by modern standards, and the island large and awkwardly placed for a plane with the landing speed of the U.N.C.L.E. jet. But Illya throttled back until their air speed barely sustained them in flight, and started down the glide path.

There was a speck in a bright orange suit standing just below the near edge of the deck, and his arms waved frantically as they approached. Illya corrected his angle slightly, then more. Port wing still too low. He pulled at the wheel and kicked the right pedal to maintain the exact direction, and then the deck was leaping up at them. He pulled the nose up violently and cut the power to both engines as the leading end of the deck whipped under them.

There was just a moment of weightlessness, and then Napoleon's chair tried to slam the base of his spine through the top of his head, and almost succeeded. They bounced several times, and canted several degrees to one side. And then all was still, except for the sound of the turbines as their penetrating whine wound down the long chromatic scale towards silence.

Illya was the first to get his seat-straps unfastened and kick the door open, but Napoleon was close behind him. Figures were running across the deck towards them and their plane, and they ran away from it. Theoretically, it could be about to explode, and these sailors were risking their lives to extinguish the fire before it did any more damage to the plane or to their ship.

A foam wagon screeched up and began squiring detergent-laden spray over the blazing engine, and the flames vanished in seconds. A crew in asbestos suits hurried in and began checking to make sure the blaze was safely extinguished.

As they stood in their sweat-stained flight suits, Napoleon and Illya heard footsteps behind them even as the fire was brought under control. They turned to see a short, bearded man in a blue uniform with ranks of gold braid on the sleeves, who addressed them in English.

"Your plane may not be severely damaged," he said, "but I must tell you that you have by accident fallen into a very...embarrassing situation. We are on a mission of extreme secrecy, and you must stay as prisoners for some time. You will be well treated, but you cannot be allowed any contact with the outside world for a few weeks, perhaps less. I am deeply sorry, gentlemen—consider that a comfortable prison for two weeks is better than a watery grave for eternity." He spread his arms and four armed guards stepped smartly forward.

"Do not think badly of me," he said. "You will soon be free, possibly with your jet repaired in our shops on board, and allowed to continue your flight to Yaoundé in Cameroon."

They looked surprised and he nodded. "Yes, I checked you out before I decided to save your lives. I am entrusted with this ship, and our mission is one which might attract spies or agents of foreign powers. But since your flight plan was perfectly plain and had been filed a week ago, before we ourselves knew our assignment, you could not have been here but by unhappy coincidence."

He turned and started towards a hatch. "Come," he said. "You cannot even be allowed the freedom of the ship, for some days yet."

The guards bracketed them, and the two U.N.C.L.E. agents proceeded to follow the Captain of the treasure ship down companionways and passages deep into her steel heart.

Chapter 15: "Accidental Misfire."

Alexander Waverly leaned back from the communications console and set his unlit pipe in an ashtray. His face looked tired, but his eyes were hard. Fifty hours had passed since his two top agents had disappeared into the South Atlantic, and not a word had been heard from them since their jet had gone down in flames. He had no choice now but to believe they were dead.

He felt no grief—he had sent too many men to their deaths in the line of duty to feel any more than a cold anger which he buried and directed at the enemy who made this constant cost necessary. A man in his position could afford to have few friends, and none within his own organization. He remembered Napoleon Solo only a few days before envying his desk job, and a thin, bitter smile creased the corners of his mouth. It was so easy to die...but others must live to carry through the job.

There was still a chance that either or both of them might still be alive, but hope had no place in an all-or-nothing game. When you were risking the lives of a billion people and the safety of the entire world, you played only on sure things.

But what did you do when there were no more sure things? It took a gambler's cool courage and evaluation of odds when the human chips were down to know the winning cards, bluff, bet and play, and still rake in the pot.

Napoleon Solo had possessed this talent to an extent his partner, for all his intelligence and technical capacity, could never attain. His instinctive ability to slip through the smallest loophole in Fate's contract had brought him back from disaster and worse time and time again. Waverly hoped for the sake of the organization—his organization—that it would this time. But now there was no way of knowing, and the odds were dropping.

No computer could have told when the odds shifted to favor the alternate attack. But Waverly was always a percentage player—almost always. And now the time had come to split the bet, call the bluff, and wait for the last card to fall. And if the other player really held the winning hand, to pay the score without regret.

He tapped a button on the communication console and said, "Get me a secure line to NASA headquarters in Washington. Doctor MacTeague."

It was perhaps thirty seconds or so before the crisp voice answered. Waverly spoke in cold, precise tones, describing their findings and their theory as to the nature and origin of the Monster Wheel. MacTeague had been appraised second-hand and in no detail; it was necessary that every fact be laid before him now.

Waverly set them forth in short, crisp sentences. When he finished, he said, "Doctor, a few days ago it was decided we could not risk a direct attack on the Wheel. Now I must report that in my opinion it is the only possible course remaining open to us."

MacTeague was not a professional bureaucrat; his position depended not on votes but on his performance and his efficiency. He took only a moment to say, "All right, Waverly. You know the situation and I don't. You yourself admit the possibility that they might not be bluffing. It may be a small one, but we have to reduce the danger of retaliation. Remember, more than one hundred million lives hang in the balance."

Waverly nodded. "I am aware of the stakes, Doctor. And you are aware there is very little time left to resolve the situation. If that payment is made successfully, it will be only a matter of time until there is an actual Monster Wheel capable of all this Wheel has threatened. Admittedly the United States of America is being risked, but the stake includes the safety of the entire world. And if we refuse to take the chance, we will almost certainly lose by default."

"I'm sorry, Waverly. I really think I do understand the full situation. But my first responsibility is to the people of this country. Unless you can give me some additional factor in our favor, I cannot allow a missile to be launched at the Wheel." He paused. "I'll grant this: I will order a test probe capable of carrying a thermonuclear device prepared for a launch. It will be ready when—and if—you can find a way of bettering our odds. Right now all we have is a theory on which, frankly, I would be willing to risk my own life—but not the lives of a hundred million citizens."

Waverly said something to acknowledge, and pressed the disconnect button. He sighed deeply and leaned back in the chair. Absently he picked up his cold pipe and puffed at it for several seconds before realizing that it was still unlit. He stared at it vaguely, then set it down and leaned his head on the back of the chair and stared at the light metal ceiling.

Almost a quarter of the way around the world Napoleon Solo lay on a bunk and also contemplated a metal ceiling. The bunk was comfortable, the room was air-conditioned, the food was fairly good and regular. Personally, he had no complaints—unlike his partner, who was currently standing near the middle of the room, his head turning uncertainly from side to side.

"They don't have the room bugged, Illya. I'm sure of it. Now stop worrying. They would have no earthly reason to plant a bug in the first mate's cabin, and no time to rig a good one in the few minutes they had before we were booked into it."

"All right. Besides, if it is bugged, we've probably given ourselves away by this time."

"Be honest—what you mean is I have given us away. And since we've gotten no reaction from anywhere it becomes increasingly obvious that I haven't. So stop worrying and relax."

Illya looked down on the American. "You look so relaxed it bothers me. What do you have up your sleeve?"

"Absolutely nothing but my trusty right arm, old friend. They've taken everything away from us but the clothes on our backs."

"They haven't taken our shoes, or the contents thereof—we could walk out of here anytime we wanted to."

"And where would we go? The ship is still all at sea, and so are we. We may be superhuman, but there are an awful lot of men on an aircraft carrier, even one this small. And since I haven't eaten my spinach today, I don't quite feel up to taking it over and turning it around single-handed."

"Not single-handed," said Illya. "After all, you've got me."

"All right," said Napoleon reasonably. "Double-handed, then. Even with my faithful Russian companion it's more of a job than I feel up to at the moment." He tapped at his chest and coughed experimentally. "Now maybe in another day or two I'll feel better. Sea air often does wonders for my constitution. When we get to wherever we're going, then you and I will have someplace to jump to if the going gets rough. Besides, our assignment was essentially to interrupt the transaction before the bird people flew away with the goodies. Wouldn't it be more fun to snatch them from their very claws?"

"And wouldn't you feel foolish if we missed?"

Napoleon shrugged, which was not easy while lying on his back. "There's nothing we can do now," he insisted. "We'll wait until there is." And as far as he was concerned, the subject was closed.

The Florida sun was touching the horizon behind them as they passed the armed guard at the door of the blockhouse, and the heat of the day that had just ended radiated back at them from the concrete block walls. Alexander Waverly removed his hat and passed a handkerchief across his moist forehead as the steel door closed behind them. A mechanical voice somewhere said, "X minus two hours and counting."

Doctor MacTeague found a pair of padded chairs with a reasonably unobstructed view of the control area and lowered himself into one. "The broadcast has been prepared," he said. "The range safety officer will send it off about thirty seconds after the course correction has been made for a collision orbit. It'll be broadcast on the same frequency the Wheel uses to talk to the ground, as well as on the International Distress frequency and a half a dozen other reasonable frequencies including the one that carries the world standard time signals from Greenwich. If there's anyone on board that Wheel listening, they'll hear it."

Waverly took the other chair while MacTeague talked. Now he said, "How long will the total orbit take from launch?"

"About half an hour. The correction will take place about plus seven minutes. Have you heard anything from those two agents of yours?"

"No. It's been four days. The one piece of actual reconnaissance we dared do showed the ship this morning still on course, approaching the island of San Juan de la Trine, about seven hundred miles south of the Cape of Good Hope. It looks as if this missile is our last hope."

"I wish it was a sturdier one." MacTeague sighed, and shook his head. "If you're wrong about this, and they're not bluffing..."

"I am quite aware," said Waverly tiredly. "I will be responsible for the destruction of the United States of America."

"I don't suppose the responsibility really matters so much," said MacTeague. "If you're right, they will never know. And if you're wrong, there will be no one left to assign responsibility anywhere—let alone in a position to know what really happened. If that's any comfort."

"Not especially," said Waverly, and lapsed into silence. The decision had been made and implemented—the only decision possible under the circumstances. And now it simply had to be waited out. He fumbled for his pipe and tobacco, and began fitting one into the other.

It was dark outside the porthole, and only a single light burned in the comfortably furnished cell containing the two U.N.C.L.E. agents. There in semi-darkness, both minds were working vigorously.

"Did you once write, 'A poet can survive anything but a misprint'?"

Napoleon thought a moment and said, "No, I'm not Oscar Wilde. And it's everything, not anything."

With time weighing on their hands, they had returned to their game of Botticelli. At the moment Illya had two and Napoleon was currently defending, with a "W."

Illya lay back with his feet up and thought. Solo had a strong predilection for American poets, but so far only the literary field had been established by his free questions, so he was unrestricted in the nationalities he chose. "Did you write 'Jacques Bouchard'?"

Silence followed. There is a lot of silence in the game of Botticelli, either preparing questions or searching for answers. Napoleon finally decided he didn't have this answer and said so.

"Pierre Wolff," said Illya. "You should pay more attention to the European theater. Now: Are you an American?"

"Yes."

"Thought so. In that case..." He went back to his mental file of American writers and was leafing slowly through it when the ship's engines stopped.

Both sat up. The faint distant throbbing had surrounded them for three days, until they were no longer aware of its presence. Then suddenly they were aware of its absence.

Napoleon spoke first. "Well," he said. "We seem to have arrived."

Illya rolled to his feet. "Fine. Now do we take over the ship?"

The American held up a restraining hand. "Not so fast, you mad impetuous Russian. There are many factors to consider. After all, it will take some time to unload all the cargo we think is here—unless they're throwing the ship and crew into the bargain..." He stopped short, and a thoughtful look darkened his face.

Illya smiled. "You hadn't thought of that, had you? They might not even bother to unload the gold. This is a good place to store it."

"And it's a good place to hijack it from. No, I think they'll put it in a secret cavern somewhere." He got up and went to the porthole, cupping his hands around his face and peering out into the night. "I wish I could tell where we are."

"No street signs visible?"

"Not even any lights. For all I know we may have stopped in mid-ocean, to transfer the cargo to a submarine."

"Or a dozen submarines. That much cargo is a lot of volume as well as a lot of weight."

"Wait a minute. There's something. Turn out that light, will you? Thanks." He looked long through the small porthole, then spoke again, and a deeply satisfied note was in his voice. "All is very well. There is an island out there, and we're lying to about a quarter mile from shore. I can see some buildings on the island—there's a moon. And I think I see what we were hoping for. There's something that looks like a radome on top of a hill maybe half a mile up from the beach." He stepped away from the window. "Come on and take a look. Our goal is in sight."

"Somehow," said Illya, "every time you say that it means we're in for a fight." But he came and looked, and eventually nodded. "It's a radome. Probably where they broadcast the signals to the Wheel."

"I wish we had our communicators."

"And I wish we had our guns. I also wish we had a battalion of Cossacks and a few tanks."

"I doubt if the Captain could supply us with those, but he has our radios—and our guns. And my cigarettes, come to think of it."

"So we walk up to him, explain the situation, and ask for them back?"

"No," said Napoleon regretfully. "He strikes me as the kind of man who would obey orders no matter how ridiculous they seemed. We'll just have to take them by force—or by stealth."

Illya expressed resignation. "Lead the way," he said.

As the moment approached for the launching, an air of tension quite out of proportion to the size of the firing grew in the quiet dimness of the control center. Every man there knew the actual mission of the missile on Pad Four. They had been briefed after the door was sealed.

On one monitor speaker the familiar voice of the Wheel droned in Esperanto about the beauties of outer space. The tracking station at Johannesburg had begun relaying the signal as soon as the satellite had cleared the horizon there.

The local controller's voice was steady over the loudspeakers as the last minute was ticked off by the hundreds of synchronized clocks inside the control system.

When the time came, only the faintest vibration was felt inside the building. On television screens the missile was surrounded by a cloud of smoke, and then it stood like a spike from the boiling clouds. It grew on a stalk of flame from the blasted earth, gathering speed until it pulled its taproot up after it and vaulted into the sky and was gone. Only a radar trace showed its path.

Attention shifted to a plotting board. The Monster Wheel was there, in its orbit safely away from the path of the short red line of grease pencil which already had a visible extension southeast of the peninsula of Florida on the map.

And the voice was counting again. "Coming up on minus five minutes to course correction. Mark. Minus five minutes."

Waverly found that his pipe had gone out, and the bitter taste of cold, used tobacco crept up the stem into his mouth. He grimaced, and spat into a wastepaper basket. He glanced at his companion, who reclined in his chair without a sign of tension—except where his hands gripped the arms. Waverly smiled slightly to himself, and started to clean the pipe.

"Course correction minus four minutes."

One of the detonators from the hollow heel of his shoe had opened the first door that stood between Napoleon Solo and freedom. The sound it made was not loud, and as hoped the crewmen were not thronging in the corridors. "Probably all up on deck," he whispered to Illya as they crept out and started for the Captain's cabin.

It was not difficult to find—they had been taken there for dinner shortly after their crash, and there had been relieved of all their possessions and had watched them being locked in the safe. They had received in return the Captain's assurance that the goods would be safely restored once this mission was completed and they could be sent on their way.

The Captain was probably on deck with his crew, supervising the unloading of his precious cargo. His door did not require the expenditure of another detonator, but the safe door did.

"Shameful security they have on this ship," said Illya disapprovingly as they blew the safe. "We should probably write them a letter about it when we get home."

"I wouldn't," said Napoleon. "We may need to do this again sometime, and I would rather it was easy."

"That's the trouble with you," said Illya. "You're soft."

There was a sharp sizzling sound and a whap! like two padded boards being slapped together as the charge went off. A bit of smoke dissipated quickly and revealed the safe door hanging by one hinge.

"Sloppy," said Illya.

Napoleon shook his head. "You're just full of criticism tonight," he said. "Right now we're in a hurry."

"We could have taken ten or twenty minutes to feel out the combination," he continued as he began to rifle the safe, "and risked being walked in on if the Old Man wanted a drink. That would have taken some fast explaining. Our absence won't remain a secret very long anyway, and I'd much rather...Ah! Here we are. He is, at least, an honest man." He tossed Illya his automatic, and pocketed his own U.N.C.L.E. Special and the Gyrojet that had saved his life twice so far. He handed Illya one of the communicators and kept the other, then snapped open his cigarette case. "Bless his little heart," he said as he checked the contents. "They're all here."

"I'm sure his mother would be proud of him," said Illya. "Now that we have the radios, shouldn't we check in? We've been out of touch for three days, and they might start to worry."

"We can wait a little longer. Mr. Waverly has more things to worry about than us. Besides, if we did call him, he'd only say, 'Well, Mr. Solo, do you have that job done yet?' and we'd have to tell him we don't. And I'd be ashamed to do that after three days. So let's go finish the job..."

"... And then we'll call him," said Illya. "All right. After three days another few hours won't matter."

"It's not irrevocable, Waverly," said Dr. MacTeague. "You can still have it stopped."

"My orders are not valid here," said Waverly. "You can have it stopped."

"I will not do so unless you recommend it."

"Then, my dear sir, it will not be done," said Waverly with cold finality.

And they sat and listened together as the last seconds trickled away in metallic clatterings of the loudspeaker.

"Five...four .. . three...two...one...

"Zero! Course correction implemented." Pause. "Radar check reports correction accurate. Collision minus approximately twenty-two minutes."

"Ready with radio transmission," said another voice. There was a wait of almost a minute, and then the voice said, "Calling Space Station One. Calling Space Station One. This is Cape Kennedy Control. Calling Space Station One. This is Cape Kennedy Control. We have had an accidental misfire, and a small missile has left its planned orbit. The ground destruct mechanisms have failed to operate. It will approach your orbit in twenty minutes, forty-five seconds. Coördinates relative your position three-twenty degrees polar, azimuth minus fifty degrees, plus-minus five degrees on both. This is not a hostile missile. It is an accidental misfire. Destroy the missile. Repeat—destroy the missile."

The voice of the Wheel chattered on inanely, as the message began to repeat.

MacTeague and Waverly looked at each other in the cool darkness of the control center.

"Now," said MacTeague, "it is irrevocable."

Chapter 16: "Dauringa Island Calling The World!"

Floodlights sparkled on the surface of the ocean on the landward side of the ship, and voices shouted back and forth from the deck to small boats which bobbed on the night-black water.

The seaward side was unlit, unwatched, and nearly deserted. The control tower which rose from the starboard side of the flight deck cast a broad dark shadow across the midnight sea. And within that shadow two men quietly lowered a convenient lifeboat. The davits were well-lubricated, and not a sound betrayed them. In a matter of minutes they were free of the ship and pulling their oars in the direction of the open sea.

It was some time before they were far enough away from the ship to turn; then they rowed parallel with the shore for almost half a mile. The illuminated area was large, and their success was of greater importance than the few minutes which could be saved by a more direct course.

They had been rowing with only the stars and the distant lights from the ship to guide them for almost an hour before Napoleon whispered, "Up oars!" In the silence that followed, he could hear clearly the hiss and rumble of breakers behind him. Beaching a small boat through surf is a great deal more difficult than swimming through it in scuba gear, and neither their guns nor their other gear was waterproof.

He shipped his oars and turned in his bow seat to face ahead, then whispered over his shoulder to Illya, "We're coming up on the surf. Get set for a few strokes with all your weight when I give the word."

His partner grunted acknowledgment, and Napoleon opened his eyes wide, reaching through the darkness for the frothing lines of white that would mark the shore.

The soft repeating hiss grew as they neared the beach and then he could see the foam. The little boat rocked violently as a wave rose up and swept under them, and Napoleon said, "Now! Hit it!"

Illya hit it—three powerful strokes with the oars that drove them along the trough of the following wave. The water rose as the wave overtook them, lifting them up as he shipped the oars and grabbed the gunwales, and then, with a swoop like a high-speed elevator, leveled itself out upon the sand with a muffled roar, sank away in a welter of white suds, and was gone.

Napoleon leaped out of the boat and grabbed the bow. "Come on," he said. "We've got to get this under cover."

Together they dragged the boat up the narrow hard-packed beach and into the shelter of the first row of vegetation. Then they crouched in the shadows for several minutes listening for any evidence of their detection.

Finally Illya spoke softly. "So much for their security systems," he said. "Napoleon, do you realize how many times we have breached Thrush's walls in the last few weeks?"

"Yes," said Solo. "Approximately twice. And if you will remember, it hasn't been exactly easy either time. Would you feel better if they caught us?"

"Well, no. But I wouldn't be so worried. There ought to be guards patrolling the island."

"Why? Nobody could get here without being detected."

"Unless they came underwater, like we did on Dauringa. And I imagine they'll be taking steps to prevent that, now, too. And in addition I still expect some kind of beach patrol."

"So do you want to wait for them?" asked Napoleon. "Let's move inland."

They navigated across the island by the stars, keeping the Southern Cross ahead of them and slightly to their right. They had been under way for almost an hour, proceeding with all caution, when the crest of a rocky hill fell away in front of them and they saw their destination on the next peak, less than half a mile off.

It squatted like a great white puffball fungus, pale against the ocean horizon in the light of the southern stars. Faint lights shone here and there through openings about the building at its base, and other small buildings clustered nearby as if seeking protection.