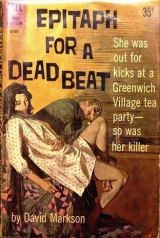

Текст книги "Epitaph For A Dead Beat"

Автор книги: David Markson

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

CHAPTER 25

Someone had invented a magic time machine which gave men back their youth, and now in the machine Michigan’s all-time football team was playing Notre Dame in a stadium on the moon. Tom Harmon was on the field, and Willie Heston and Germany Schultz were twenty again, and Harry Fannin was all in one piece. Quarterback Bennie Friedman called the signals for my wide sweep to the right, the ball was snapped back, and up ahead a hulking lineman named Oliver Constantine pulled out to lead my interference. The screams of a hundred thousand fans thundered in my ears. “Go, Fannin, go—”

I lifted my face out of the blood.

We went back into the huddle. Ducky Medwick was calling the plays now. Ducky Medwick hadn’t gone to Michigan. On top of which he’d played baseball, not football. Did it matter? It was only a private fantasy anyhow. “Take it again, Harry, we’ll go all the way this time—”

I dropped my face back into the blood.

They shipped me down to the junior varsity, and I couldn’t make first string there either. I sat on the bench and glared at the players who beat me out, like Truman Capote, Liberace, Clifton Webb. I turned in my uniform.

This was ridiculous. Klobb’s studio was less than ten yards away. What would have become of western civilization if a little travel had ever fazed Leif Ericson, say, or Linda Christian? Come on now, Orville, you can get that thing off the ground.

I crawled to the studio. It didn’t take any longer than the voyage of the Pequod.I was carrying Moby Dick on my back and Moby was carrying Captain Ahab on his. Why the hell should I carry Ahab? All he had to complain about was a wooden leg, and I had a wooden head. Splintered. I dragged myself through the door, across a large room which reeked of turpentine, into a bathroom. Ahab, you hab, he hab. All God’s chillun hab, except Harry.

I lay there, not wanting to get up and wondering why I’d thought of Ducky Medwick when I had football in mind. Oh, sure, because I’d seen him get smashed in the skull by a pitched ball when I was a kid. They’d carried him off the diamond and I’d cried because I thought he was dead. But he’d come back to play again.

There seems to be a moral there, Fannin, if you’ve got sufficient wit to find it.

I was staring at a bathtub. I got the faucets turned for the shower, and then I squirmed over the side, flopping. That was ridiculous too. Let’s go, Ishmael, on your feet. The white whale was still on my shoulders so 1 hoisted him also, clinging to a towel rack.

I remembered the revolver Klobb had returned. And my wallet, with all those engraved pictures that ought to have been of Marilyn. I fished them out of my clothes and dropped them onto a mat. My ribs felt as if they were removable also, but I didn’t experiment.

The roof of the john was glass, like the rest of the structure. Jolly. Nothing like a shower under the stars at five in the morning, especially in your best suit.

I sat down on the edge of the tub to let myself drain, like Katharine Hepburn after she fell into the pool in Philadelphia Story.Did Katharine Hepburn fall into a pool in Philadelphia Story?She should have, if she didn’t. It was the first enjoyable vision Td had since Dana dropped that towel.

I limped back into the other room, making squooshing sounds. A big place, a sloppy place, hardly anything to lean on at all. Paintings on stretchers, paints, rolls of canvas, cans of oil, drafting tools, brushes, filthy rags – and what I was looking for on a chest in a corner. A half-full bottle of gin. Sweet, medicinal, London dry gin. Id have my cup of kindness yet.

The bottle wasn’t any harder to lift than an anvil. Could Ducky Medwick have lifted it? Certainly Medwick could have lifted it. Here’s to Medwick.

There was something on a wall near me that might have been a mirror. If it wasn’t a mirror it was a portrait of someone who’d been buried at sea. Whichever it was, I hoped they didn’t let in children who weren’t accompanied by adults.

It was I, ah sadness, it was I – battered as a bull fiddle, bruised as a fig. There was still a trickle of blood from the deepest tear, where the recoil reducer on the Beretta had taken me. To think I’d given them back that magazine, or she wouldn’t have been carrying it – this the unkindest cut of all. My cheeks were raw and swelling. I took another drink, a sorrowful drink, this time for Pistol Pete Reiser of the old Dodgers, who used to run head-first into concrete outfield walls.

There was alcohol in the John, and I bathed the gashes. They would have heard me in the Bronx if I’d had any sensation above my neck. I found gauze and patched the worst of the mess.

I could work my jaws. Maybe Pete Peters was right about that religious awakening in the air – maybe it was a time for miracles, maybe nothing was broken.

Maybe it was time for another drink. Was it? Of course it was. There was nothing else up there for me anyhow, except misery. To Ted Williams, who cracks bones and spits in the face of adversity.

I retrieved my wallet and the Magnum. I put them away, then reached a cigarette out of my shirt. It fell apart in my hands. I could have used a cigarette. Ah, well. I had a nip for Nile Kin-nick of Iowa, a fine halfback who’d crashed in the war.

I wondered what Klobb would do about his showing next week. I cared. I had a drink for Leslie Howard, who’d also crashed, and for General Gordon whose head got hung on a spear. Poor Leslie Howard. I had one for Billie Holliday. They were small drinks but the feeling was what counted. I had a smaller one for Gunga Din, who was a better man than I was, which was decidedly not much of an achievement. I had half of one for Oliver Hazard Perry, just because I liked the name, and then I had the other half for Dred Scott. There were about six drinks left when I heard the noise.

I was near the studio door and I breast-stroked behind it. I could just see across to the roof doorway through the crack.

The door had been pushed toward me. A shadow hesitated along the wall. Maybe it was theShadow. Who knew? The Shadow knows – heh, heh, heh. The weed of crime bears… or maybe it was someone from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. I took one more quick one for Lamont Cranston, just in case.

Never mind the stupid bottle, you cluck, a voice said. Don’t you think maybe it’s about timeyougot the jump on somebody? You’ve been bopped by a Beatnik, cuflFed by a cop, pounded by a pander….

I took the hint. No need to tell Mrs. Fannin’s boy Harry anything a second time, no sir. I reached into my holster.

My son the detective. I’d put my wallet in the holster. I found the gun in the pocket where I keep my wallet on days when I wake up knowing my name.

The shadow advanced an inch or two. I tilted the revolver downward. Water dripped out of the barrel onto my shoe.

I supposed I could always throw it. Although I’d hand-loaded the cartridges myself, a little dampness was not going to make them defective. Never. Nothing defective about this detective. I suppressed a giggle.

But they were still well-sealed cartridges. Cartridges? Hmmm. I broke open the cylinder. Well – sincere old Ivan, he’d really meant for me to shoot myself.

There was still no activity over there. I was crouching now, like Pat Garrett in that room in Fort Sumner in 1881, waiting to lay out poor Billy the Kid. From 1881 to now was seventy-nine years. Billy the Kid had been twenty-one. If he were still alive he would be exactly one hundred years old. I hoped it was Billy the Kid. Most likely he would be sort of sickly, too.

The shadow finally spoke. Just a cautious whisper. “Ivan?”

I let him wait. I had a snort for Joe DiMaggio, the real one.

“You in there, Ivan?”

“ Hrlggr,” I said clearly.

Ephraim. Old son of a gun Ephraim, Bard of Beatville. The seersucker Swinburne. He stepped across the sill timidly, paused, then came toward the studio. On little cat feet, like Sandburg’s fog, and as quiet as a Robert Frost snowfall. There was nothing lethal in his hands. No gun, no switchblade. Not even an Oscar Williams Treasury of Mongolian Verse.

“Ivan?”

“It’s me,” I said. “Geoffirey Chaucer.”

“It’s—?”

He drew up short, halfway over. For a minute he wavered on his toes, like a kid caught at the cookie jar. Like an architect of epic odes, espying the esmoked oysters. Oysters were animals, not fish. I hoped they weren’t neurotic about it.

“Het your gands up,” I said.

“Huh?”

I stepped out and waved the gat at him, snarling like the desperate character I was. Dauntless Fannin, ominous as a crocheted doily.

“My God, what happened to—?”

“Ha! Don t ask,” I said. I’ve been suffering, young Turk. Little does the crass world know. Anguish, agony – just wait until I get it written. It’s going to be the greatest spiritual exercise since Peyton Place.I’ve even had visions, all sorts of people I haven’t thought of in – say, listen, do you have any idea whatever happened to Wallace Beery? It just struck me that I haven’t seen him since—”

“What?”

He was shaking his head, frowning at the bottle. “Take a belt,” I told him. “We’ll drink to Sacco and Vanzetti.”

He didn’t want one. Very slowly he started to back away from me. I took a step after him. I stopped abruptly when my ribs took a step in the opposite direction.

“Don’t leave, like,” I told him. “Let’s have a sermon or something.”

“I don’t have anything to say to you, Fannin.”

“Sure you do. We’ll parse sentences together. Do a textual exigesis of The Cantosof Jayne Mansfield. We’ll talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs, make dust our paper and with rainy eyes write sorrow on the bosom of the – hold it right there.”

“You’re flipped, you know that? You better get to a doctor.”

He kept on backing off, a small, homely man, confused and frightened. So why didn’t he stop when I waved the revolver?

“This is a Colt Three-Fifty-Seven, Ephraim. A Magnum. You know what a Magnum is? It could splatter your frail brains from here to Xanadu, cut you off before you finish your first sonnet sequence. Think of it, The Efforts of Ephraim,left undone—”

“I didn’t kill them, Fannin. You know that—”

“Maybe. What the hell – not maybe, let’s say probably. But we still have portentous matters to discuss—”

“Say, I’m serious about a doctor. You look terrible.”

“I do not love thee, Doctor Fell – the reason why, I cannot tell.” I laughed senselessly, cocking back the hammer on the gun. “Enough of idle literacy, Ezra. Leave us converse.”

“You won’t shoot me, Fannin.”

“Won’t I? Ha! I shoot poets just for practice. Bing – smack in the middle of the iambic pentameter—”

He stepped over the sill.

“Damn it,” I said.

“People don’t kill other people,” he said.

“Sure they don’t. How many of your ex-girlfriends are dead who were reading Dylan Thomas within the week? Listen, they shot Gandhi, didn’t they? They shot Draja Mikhailovitch and Private Prewitt. They even shot Eddie Waitkus – you remember, that first baseman—”

“People are good, Fannin. People have beautiful souls.”

“Come back here, Ephraim.”

“You won’t shoot.”

“Come back,” I said. The door closed. I started to laugh again, like a maniac. “Shane,” I said. “Come back, Shane—”

I had one last fast one for Brandon deWilde before I followed him.

CHAPTER 26

I didn’t run. The stairway was treacherous enough without my showing off. My chest was burning. When I reached the sidewalk a lamppost fell against my shoulder so I held it up for a minute, listening to it wheeze.

There was something under my feet at the curb. An abandoned canvas deck chair. If the fire in my ribs spread, I could be the boy who stood on the burning deck chair.

Ephraim was a block away, trotting toward Seventh Avenue. I made it across to the Chevy.

Was I in shape to handle a car? Don’t bother me with foolish questions when I’m driving. Clutch in, brake off, starter down and we’re rolling. Rolling? Hmmm…

I put the key in the ignition.

Come on, Ahab, get those lifeboats over the side, eh? I swung out sharply, reversed, then made a U-turn that put me facing the wrong way in a one-way street. Signs, signs, everyplace signs. But what did they mean in a spiritualsense, what did they say about man’s true estate? Anyway there wasn’t any traffic.

I saw him cut across Seventh on an angle, turning north. I tooled up there and then slowed again, nosing just far enough into the intersection to get a look. Peek-a-boo. Ha! He was a hundred yards off, turning east again.

I waited a few seconds and then followed him, cruising in low gear with no lights. He glanced across his shoulder once or twice, but only along the sidewalk. Old Ahab, I’d forgotten to drink to his hollow leg. My own wasn’t hollow, but some things would have to wait.

I pulled up at each crossing, idling for as long as I could see that barley hair bouncing above the parked cars, then moving ahead. He made several turns, keeping to back streets except to cross Sixth, working steadily north and east. He had slowed to a walk.

When he hit Macdougal he cut south again. And then I lost him.

I gunned up fast. His head had been clearly visible and now it wasn’t. I stopped, listening.

He’d evaporated like Marley’s ghost.

Marley? Oh, sure, Marley was dead, dead as a doornail. A cliché, or had Dickens invented it? You’re not that potted, Fannin. Poets don’t just vanish.

Up? There were stairways rising to first floors, but the doors were all above the level of the cars. Not up.

Down? Hmmm, down. More stairs, leading into basements and storage cellars. Almost every one of the entrances was blocked by a chain. One of them was swinging slightly, almost imperceptibly. Come back, chain.

Was that sleuthing or wasn’t it?

You down there, Jacob Marley? Don’t try to kid me, Jacob. Not your old partner, not Ebenezer Scrooge.

Darkness. There would not be more than five or six steps, but I could not see the last of them. Hungry aardvarks might have been prowling in a pit at the bottom, wooly bears, boll weevils.

Did it frighten me? Nothing frightened me. People were good, people had beautiful souls. My baby-faced Byron had told me so. My bow-legged Baudelaire. I took out the gun I wasn’t going to shoot any beautiful souls with.

I bent myself under the chain. My shoes squeaked.

Five steps, and then a flat concrete landing. A wooden door swung inward at the barest touch.

The mouth of an alley, very much like the one which had led to McGruder’s. Darkness here also, but not absolute darkness. Back at the right an oblong shaft of light, spilling out of a window at ground level. A high brick facade unbroken along the left. Silence.

Marley? Bob Cratchit? Tiny Tim?

Humbug.

I went down on a wet knee at the window, bracing one arm against my ribs. Miss Fannin’s gowns by Davy Jones, special effects by Oliver Constantine. The miseries of the hero in no way reflect the interests of the sponsor. The window was the type that hinges inward. It was propped open by a paperback book.

Dr. Zhivago? Dr. Spock?Wrong as always. Not even The Metaphysical Speculations of Tuesday Weld.Something called Walk the Sacred Mountains,by one Peter J. Peters. There was an L.P.. record on the ledge beneath it, a session by Thelonious Monk.

I looked in. A small room, a bulb inverted from a cord in the ceiling. A black ceiling. Black, Ebenezer? Certainly black, saves on cleaning costs. Black walls also.

There was a cot opposite me, draped in a bleached sheet which hung to the floor. The only other inanimate object in there was a fluffy, snow-white rug, with two men and a woman sitting on it.

They were sitting cross-legged, like Burmese idols. The woman was a spindling, horsey blonde I might have noticed at the party. One of the men I didn’t know. The other was Don McGruder.

Dashing Don McGruder, mournful footnote from a psychiatrist’s case book. Whatever the diagnosis was, it was catching. This time the other two didn’t have any clothes on either.

God bless us, every one. For this I’d struggled out of a sickbed. But maybe I’d write a book now myself. By H. Fannin-Ebing.

There was an oriental water pipe in the middle of the rug, and they were passing its stem from mouth to mouth. I watched the blonde suck in smoke, then hold her breath. She had a bosom like a mine disaster. Even through the window the sweet stench of the marijuana was overpowering.

“They don’t comprehend,” the girl said. She slurred the words. “‘Get married, Phyllis’—that’s all I hear. What a drag. I love them, I really do, but they don’t dig me, you know? They just weren’t with it at all when I asked for the money for the abortion—”

“This isn’t swinging me tonight,” McGruder said. “It simply isn’t. I’m not high in the least.”

“Recite us some Kerouac then, Donnie. You do him so passionately. The part where he talks about how they make love in the temples of the East—”

“If you really want me to—”

She wanted him to. By the old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin’ lazy to the sea, there’s a Beatnik girl a-settin’, and she’s gettin’ high on tea. I was sorry I couldn’t stay, but I had a previous appointment.

I had an appointment with Fagin. We were going to teach a few middle-class youngsters some of the nicer subtleties of felonious assault.

I wondered if they would have a jazz band at that monastery when I got there. If I stole the instruments, would that make me a felonious monk?

There was a turn farther back as I’d anticipated, but at the rear of the building I was in total darkness again. I found a door frame by touch. The door was open.

A hallway. Fifteen or twenty feet inside I saw a tiny wedge of light which would be the room I’d been watching. There could have been other doors in there.

I hesitated a minute, feeling dizzy. I couldn’t hear them from across in that room. I pulled back the hammer on the revolver, making noise with it, then uncocked it again soundlessly.

“Ephraim?” I said softly. “That’s that Magnum, Ephraim.”

The place was as quiet as an unlit cigarette.

“I’m the ghost of Christmas yet to be, Ephraim. Speak to me, lad, unless you don’t want to find anything in your stocking except worms and the bones of your feet.”

“Damn your black heart, Fannin,” he said.

There was a swishing sound after the words. Something flexible and hollow struck me behind the ear, not hard, and I danced away from it. That was fine, except that the abrupt movement sent a new pain through my chest, like tape ripping. I doubled up gasping and the thing hit me again.

It was nothing, maybe a length of rubber hose. On a normal working day I could have caught it between my teeth and chewed it into pieces. I hadn’t had a normal day since they’d fired on Barbara Frietchie. Waves of murky nausea washed over me and I stumbled against a wall.

“Shoot,” he said then. “Go ahead, shoot me—”

His voice was choked and theatrical. For a minute I had the batty notion that he was going to start reciting also, like McGruder. Then I thought I heard him, I could have sworn.

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, but spare your country’s flag,” he said

Dementia, absolute dementia. He was sprinting, going away.

I let him run. I’d had it. I wasn’t even ashamed.

I dragged myself out of there like a feeble old man whose favorite walking cane was sprouting leaves under the backyard porch, just out of reach. Come back, cane.

Sick, sick. I didn’t stop to see how the literary tea was progressing, but I was perverse enough to slip the Peters novel off the ledge. Phyllis would find a husband one day, she’d be a steady fourth for bridge at the country club, a pillar. Me, I had gum on my sole.

It was almost an ultimate satirical indignity. The groaning gumshoe. There was a scrap of paper stuck there also.

It was a photo of a matronly, heavily made-up woman, torn from what looked like an inquiring photographer’s column. The woman had practically fractured her jaw for the camera, getting it lifted to erase the lines in her neck. Next to the picture it said:

Mrs. Burner van Leason Fyfe, Cotillion chairman: “Of course there’s still society in America. There just has to be. Why, what meaning would anything have without it?”

CHAPTER 27

There was a loose page in the Peters book. I stared at it without interest, leaning against a fender:

… digging it with Bennie and Jojo and those wild chicks (one of them an Arab, she had eyes like smothered stars) in the backseat of that broken down Chrysler Bennie had driven to Tampico and back and sold for forty dollars in San Diego and spent the money on a two-week fix and then swiped it back again, and all night long Jojo talking about the Mahayana transcendence of our friend Wimpy, the poet who did not wash except on the coming of the new moon and who was the new culture hero of our time and who once said:7 dig Brahman and I dig The Bird but I do not dig housewives,” which became a creed: and all the while (younger then and my jeans too tight; I’d borrowed them from a tranquil Taoist midget Td met reading Lincoln Steffens in a public urinal in Times Square – ah, holy times, holy square!) pressing my hand against the knee of that swinging angel Arab lass and not minding the blood where I tore my skin against a broken spring in the seat, oh how I suffered, telling myself as soon as I make it with this chick I will hop a freight and very religiously ride the rails to Albuquerque to tell Herman (butfirst some detail here about Herman, a raw maniac hipster kid who…

That was all I needed. I wadded up the page and tossed it in the general direction of a passing cat, then let myself ooze wetly behind the wheel of the Chevy. I’d leaked water on the floorboards, coming over. I supposed it wasn’t any worse a crime than leaking prose.

I wasn’t sure I could make it uptown. Or maybe I just wanted recognition for all my successful missions. I drove back to Fern’s.

It was almost six, and it got light in the few minutes I was in the car. I leaned against the bell, feeling rotten about waking her. After a minute I heard a window being lifted. I went down a few steps, letting her get a look at me.

“It’s Harry, Fern—”

“Harry, what—?”

She disappeared inside, and a second later the catch released. I hauled myself up the one carpeted flight.

She was in the apartment doorway, wearing that short blue jacket again. Her hair was tousled, and light from the stairwell gleamed on her naked lovely legs. Her face slackened when she saw my own. “Oh,” she said. “Oh, Harry—”

“Don’t take me out, coach.”

She extended a hand, but it didn’t look strong enough to support me. I gave her what I could spare of a smile, then went across to one of the leather sling chairs where my damp seat wouldn’t do any harm.

I sat for a minute with both arms crossed against my stomach, hearing the door close. When I raised my head she was kneeling in front of me.

Her fingers traced across my forehead, near the patch of gauze. “It couldn’t have been just Ivan—?”

“He led the cheering section.”

“You look worse than Dana did. Does it hurt badly?”

“Only when I laugh.”

“Oh, stop joking, it isn’t something to—”

“I’m okay, Fern. I shouldn’t have come. You’ve had enough for one night.”

“You can quit that also.” She had gotten up, considering me somberly.

“Have I ever told you how beautiful you are?” I asked her.

“Have I ever told you you’re a little crazy? Yes, I think I did, the other night. There’s coffee, Harry. I made some for Dana before, all I have to do is heat it—”

“Coffee would be swell.”

She shook her head, then went into the kitchen. I worked myself out of the soggy jacket. Bloomingdale’s better grade, eighty-seven bucks for the suit and I still owed them forty. Maybe the old Armenian tailor on my corner could salvage it. He was half blind from reading William Saroyan in the glare of his window all day, and he couldn’t sew a straight seam, but his Negro presser was fair. The Negro read Karen Horney and Erich Fromm.

“It won’t be a minute,” Fern said from the doorway. “Listen, Harry, why don’t—” She glanced toward the closed door to the second bedroom. “Good heavens, I’m not going to be coy. Dana will be asleep for hours with those pills. Get yourself inside and get undressed. There’s a big quilted robe in the closet if you want a hot shower—” She smiled. “Or is that what you tried to take already? Maybe you ought to just jump right into bed, you big oaf. I’ll bring the coffee.”

I grinned at her. “If you touch me, I’ll scream.”

“Go on, now.”

I left my jacket across one of the wings of the chair. A lamp on her bed table was burning, and the covers were flung aside. I gave my tie a yank, then growled at myself in a mirror over a dressing table. The wet knot was as tight as a wet knot.

There was a day-old Timesin a magazine rack, and I spread it across the small bench before I sat. Maybe the raw-honed private cop would have more luck with his shoelaces. Not tonight, Napoleon. I bent forward about halfway, which was enough to make me dizzy again. Concussion, sure as shooting.

My elbow had nudged a book on the table. It was lying reverse side up. Fern’s picture was on the glossy jacket.

“Advance copy,” she said. She had come in carrying an enormous steaming white mug. “First one off the presses.”

“I never met a famous author before.”

She wrinkled her forehead, peering across her shoulder. “Who dat? Where he at?”

She looked wind-blown in the photo. The novel was called Go Home, Little Children.A sticker on the cover said that it was a book club selection.

She put the coffee near me. “Drink it before it gets cold. I thought I told you to get out of those wet things—”

“I would of, ma’am. ‘Cepting I need a scissors for my tie.”

“Oh, here, let me—”

She leaned down, working at it, and then stepped back and gave me an exaggerated scowl. “Maybe we’ll need a scissors at that. Or a—” She drew in her breath. “Oh, damn me anyhow, I was almost going to make a joke about a knife, when poor Audrey—”

She pressed a hand across her mouth, looking away. I reached out and pulled her toward me. She came yieldingly, going to her knees again, and my hands slipped beneath that jacket. Her head fell against my chest.

She was not wearing anything under there. The soft flesh of her shoulders was still bed warm. I held her.

“It’s as if it won’t end,” she said. “Three people dead. Dana’s right, things get so terrible sometimes—”

Her face lifted. For a moment I didn’t move. I didn’t even breathe. The muscles in my jaw had gone tight, and something began to twist inside of me – into a hot sickening node, like fear or like horror.

It wasn’t fear. The book thudded to the floor as I got to my feet.

“Three,” I said. “Three people dead—”

“Well, yes, aren’t—?”

“You couldn’t have known about the third, Fern, unless—”

“What—?”

She was still on her knees. Highlights glinted in her silken hair. Her face was as delicately etched as a dream that only time itself was ever going to exorcise.

“Why?” Isaid. “Dear God, Fern – why did you kill them?”