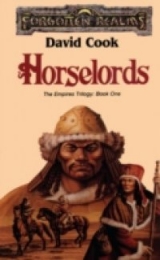

Текст книги "Horselords"

Автор книги: David Cook

Соавторы: David Cook

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

"Sit!" insisted Yamun, his speech slightly slurred. "Wine! Bring the historian wine." The khahan tore at a clublike shank of boiled meat.

"Where is General Chanar?" Koja asked, pulling his shearling coat out of the way as he sat down. He had traded a nightguard an ivory-hilted dagger for the coat and then spent the rest of the afternoon cleaning the lice and vermin out of it. Now, it was tolerably clean and kept him quite warm.

Yamun didn't answer Koja's question, choosing instead to talk to one of his pretty wives. "General Chanar, where is he?" Koja asked again.

Yamun looked up from his dalliance. "Out," he answered, waving a hand toward the fires. "Out to see his men."

"He has left the feast?" the priest asked, confused.

"No, no. He went to the other fires to see his commanders. He'll be back." Yamun swallowed down another ladle of kumiss. "Historian," he said sternly, turning away from his wife, "you weren't here when the feasting began. Where were you?"

"I had many things to do, Khahan. As historian, I must take time to write. I am sorry I am late," Koja lied. In truth he had spent the time praying to Furo for guidance and power, hoping to find a way to send his letters to Prince Ogandi.

"Then you have not eaten. Bring him a bowl," the khahan commanded to a waiting quiverbearer.

A servant appeared with a wine goblet and a silver bowl for Koja, filling the latter from the steaming kettle over the fire. The pot held chunks of boiled meat, rich with the smell of game, swimming in a greasy broth. A second servant offered a platter covered with thick slabs of a sliced sausage. Koja sniffed at it suspiciously. Aware that Yamun was watching him, he chose one of the smallest slices. At least Furo was not particular about what his priests ate, Koja thought.

Closing his eyes, the priest took a bite of the sausage. He had no idea what the meat was, but it tasted good. Fishing into his coat, he pulled out an ivory-handled knife, mate to the one that bought him the coat, and poked the meat around in the bowl, stabbing out a large chunk of gristly flesh. The meat was hot and burned his lip. Koja took a quick swallow of wine to cool his mouth.

"The food is good," Koja complimented his host.

Yamun smiled. "Antelope."

"Lord Yamun kill it on the hunt today," one of the khans said from the other side of the fire. It was Yamun's advisor, Goyuk. The old man smiled toothlessly, his eyes nearly squeezed shut by wrinkles. "He only need one arrow. Teylas make his aim good."

There was an impressed murmur from the others around the fire.

"Goyuk Khan lost most his teeth at the battle of Big Hat Mountain, fighting the Zamogedi," Yamun explained. The old man nodded and smiled a broad, completely toothless smile.

"That is true," Goyuk confirmed, beaming. Toothlessness and strong drink gave his speech the chanting drone of a soothsayer or shaman.

"What is the sausage made of?" Koja asked, holding up a piece.

"Horsemeat," Yamun answered matter-of-factly.

Koja looked at the piece of sausage he held with a whole new perspective.

"My khahan! I have returned!" a voice called out of the darkness. Chanar, still dressed in the clothes he wore that morning, lurched into the camp. He had a skin tucked under one arm, dribbling kumiss across the ground. He held a cup in the other. As Chanar got close to the fire, he stopped and stared at Yamun and Koja.

"You are welcome at my fire," Yamun said in greeting as he sipped on his own cup of kumiss.

Chanar stood where he was. "Where is my seat? He has taken my seat." The general pointed at Koja.

"Sit," Yamun ordered firmly, "and be quiet." A servant unrolled a rug on the opposite side of the fire from the khahan and set out a stool.

Slowly, without taking his eyes off Yamun, Chanar slopped more kumiss from his skin. He let the bag drop to the ground and slowly drained the cup. Satisfied, he stepped to the seat put out for him and sat down with a grunt. He glowered at Yamun from across the fire.

Koja was uncertain if he should break the silence. As he sat there, he could feel the anger forming and solidifying between the two men. The women disappeared, slipping from their seats and fading into the night.

"Khahan," the priest finally said, "you made me your historian." Koja's mouth went dry and his palms began to sweat. "How can I be your historian if I don't know your history?"

For a moment Yamun didn't answer. Then he spoke slowly. "You're right, historian." He turned his gaze from Chanar. "You've not been with me from the beginning."

"So, how can I write a proper history?" Koja pressed, diverting Yamun's attention from the general.

The question seized hold of Yamun's mind, and he mulled it over. Koja quickly glanced at Chanar. The man was still staring at Yamun. Finally, the honored general's eyes flicked toward Koja and then back to the khahan. The priest could feel the tension begin to ebb as both men's thoughts were diverted.

"What should you know?" Yamun wondered aloud. His fingers began to toy with his mustache as he considered the question.

"I do not know, Yamun. Perhaps how you became khahan," Koja suggested.

"That is no story," Yamun declared. "I became khahan because my family is the Hoekun and we were strong. Only the strong are chosen to be khahan."

"One from your family has always been the khahan?" Koja asked.

"Yes, but I'm the first khahan of the Tuigan in many generations. For a long time the Tuigan weren't a nation, only many tribes who fought each other."

"Then how did this come about?" Koja spread his hands to indicate the city of Quaraband.

"I built this in the last year—after the last of the tribes submitted to my will." Yamun explained offhandedly. "But that's not my story."

The khahan paused and sucked at his teeth. Finally, Yamun began his tale. "When I was in my seventeenth summer, my father, the yeke-noyan, died—"

"Great pardons, Yamun, but I do not understand yeke-noyan" Koja interrupted.

"It means 'great chieftain,' " Yamun replied. "When a khan dies, it is forbidden to use his name. This is how we show respect to our ancestors. Now, I'll tell my story."

Koja remembered that Bayalun had no such fear for she had named Burekai freely. The Khazari bit his lip to restrain his natural curiosity and just listen.

"When I was younger, my father, the yeke-noyan, arranged a marriage for me," continued Yamun. "Abatai, khan of the Commani, was anda to my father. Abatai promised his daughter to be my wife when I came of age. But when the yeke-noyan died, Abatai refused to honor the oath given to his anda." Yamun stabbed out a large chunk of antelope and dropped it into his bowl.

Across the fire, old Goyuk mumbled, "This Abatai was not good."

Yamun slid back from the fire and took up the tale again. "The daughter of Abatai was promised to me, so I decided to take her. I raised my nine-tailed banner and called my seven valiant men to my side." The khahan stopped to catch his breath. "We rode along the banks of the Rusj River and near Mount Bogdo we found the tents of the Commani.

"That night a great storm came. The Naican were afraid. My seven valiant men were afraid. The ground shook with Teylas's voice, and the Lord of the Sky spoke to me." The khans at the fire glanced up at the night sky when Yamun mentioned the god's name, as if expecting some kind of divine response. "The storm kept the Commani men in their tents, and they did not find us hidden behind Mount Bogdo.

"In the morning, To'orl of the right wing attacked. My seven valiant men attacked, too. We overturned the Commani's tents and carried off their women. I claimed the daughter of Abatai, and she became my first empress." Yamun stabbed the meat in his bowl and took a bite. Steam still rose from the boiled antelope.

Koja looked at the faces around the fire. Chanar sat with his eyes closed. The other two khans listened with rapt attention. Even the boisterous singing that had started at one of the nearby feast-fires didn't distract them. Yamun himself was excited by his own telling, his eyes aglow with the glories of olden days.

"Now that I defeated the Commani people, I scattered them among the Hoekun and the Naican," the khahan added as a postscript, between bites of antelope. "To To'orl of the Naican I gave five hundred to be slaves for him and his grandchildren. To my seven valiant men, I gave one hundred each to be slaves. I also gave To'orl the Great Yurt and golden drinking cups of Abatai.

"That's how I first made the Hoekun strong and how I got my first empress," Yamun said as he finished the story.

Chanar opened his eyes as the recitation ended. The khans smiled in approval at the telling of the tale.

"What happened to the first empress?" Koja asked.

"She died bearing Hubadai, many winters ago."

Koja wondered if there was a trace of sorrow in the words.

"And what happened to Abatai, khan of the Commani?" Koja asked to change the subject.

"I killed him." Yamun paused, then called to a quiverbearer. "Bring Abatai's cup," he told the man. The servant went to the royal yurt. He came back carrying a package the size of a melon, wrapped in red silk, and handed it to Yamun. The khahan unwrapped it. There, nestled in the cloth, was a human skull. The top had been sliced away, and a silver cup was set in the recess.

"This was Abatai," Yamun said, holding it out for Koja to see.

The hollow eyes of the skull stared at Koja. Suddenly they flashed with a burning white light. Koja jumped back in surprise, almost toppling off his stool. The bowl of meat and broth in his lap splashed to the ground. "The eyes, they—"

The eyes flashed again, the light flickering and leaping. Koja looked at the skull more closely and realized he was seeing the reflection off the silver bowl through the hollow eye sockets.

"What's wrong, little priest, did you read your future in the bones?" Chanar quipped from across the fire. The old khan, Goyuk, guffawed at the joke. Even Yamun found Koja's reaction amusing.

"He's dead and what's dead can't hurt us," Yamun said with conviction. He turned to Chanar. "Koja is filled with the might of his god, but fears bones. True warriors don't fear spirits."

Koja flushed with embarrassment at his own foolishness.

"We must drink to the honor of the khahan," Chanar announced, hauling himself to his feet. He stepped around the fire and stopped in front of Koja. Uncorking his skin of kumiss, he splashed the heady drink into the skull cup. He took the skull from Yamun and handed it to Koja. Unwillingly, the priest took it in his hands.

"Ai!" Chanar cried, the signal to drink. He tipped his head back and drank from the skin.

"Ai," echoed Yamun and the khans. They raised their cups and took long swallows.

Koja looked at the skull cup in his hands. The eyes were still staring at him, and the brain recess was filled with a milky pool of kumiss. He turned the cup so it wasn't facing him.

"Drink, little priest," urged Chanar, wiping his mustache on his sleeve, "or do you think the khahan has no honor?"

Yamun looked at Koja, noting that the lama had not joined in the toast. His brow furrowed in vexation with his newly chosen historian. "You don't drink?"

Koja took a great breath and hoisted the skull up to his lips. He closed his eyes and gulped a draught of the wretched drink. Quickly, before they could urge him to take another swallow, the priest held the skull out to Chanar.

"Drink to the khahan's might," Koja gasped.

"Ai," called out the khans, refilling their cups.

Chanar grinned at the look of distress that flickered over the priest's face. He took the offered cup and drained it in a single gulp. Taking the skull with one hand, he filled it again with kumiss and handed it back to Koja. "Drink to the khahan's health," he said with a wicked smile.

Koja choked.

"Ai," slurred out the khans. The toasts were starting to take their toll.

"Enough," interrupted Yamun, pushing the drinking skull away from Koja. "My health doesn't need toasting. I've told a story, now it's someone else's turn." He looked pointedly at Koja.

"I've a story to tell," Chanar snapped, before Koja could speak up. "It's a good story, and it's all true." He stepped back to give himself more space, kicking up the ashes at the edge of the fire.

Yamun turned to Chanar. "Well, what is it?" he asked, barely keeping his irritation under control.

"Great khahan, the priest knows how you beat the Commani with the help of the Naican and your seven valiant men. Now I'll tell of what happened to one of those seven valiant men." Chanar dropped the skin of kumiss and stepped away from the fire.

"Yes, tell us," urged the toothless Goyuk Khan.

Koja looked at Yamun before he voiced his own opinion. The khahan was impassive. Koja couldn't tell if he was displeased or bored, so he kept his own mouth shut.

"After the khan—the khahan—," began Chanar in a loud voice, "defeated the Commani, he gave them to his companions, like he told us. He told his seven valiant men to gather the remaining men, young and old, of the Commani. 'Measure all the men by the tongue of a cart, and kill all those who can't walk under it,' the khahan ordered."

"Measure all the men by a cart," Koja asked meekly. "What does that mean?"

"Any male who cannot walk under the hitch of an oxcart is killed. Only the little boys are spared," Chanar answered curtly. "We killed all the men of the Commani, like the khan ordered. He wasn't the khahan yet, you understand." Chanar circled around the fire, pacing as he spoke. "So, we killed the men.

"Then the khan gave out the women and children to us, because he was pleased with his warriors. He went to the seven valiant men and said, 'You and I are brothers of the liver. We've been anda since we were young. Continue to serve me faithfully and I'll give you great rewards.' He said this. I heard it said." Chanar kicked an ember at the edge of the fire back into the flames.

"The valiant men were pleased by these words." Chanar paused, looking at Yamun. "There's more to the story, but perhaps the khahan doesn't want to hear it."

"Tell your story," insisted Yamun.

Chanar nodded to the khahan. "There isn't much more to tell. Perhaps you know the tale. One of the valiant men told the khan, 'We are anda, brothers of the liver. I will stand at your side.' And I heard the khahan promise, saying, 'You are of my liver and will be my right hand forever.' When the khan went to war, this valiant man was his right hand. With his right hand, the khan conquered the Quirish and gathered the scattered people of the Tuigan—the Basymats and the Jamaqua. His right hand was strong."

Chanar's story became more impassioned. He stomped about the fire, slapping his chest to emphasize his points. "I never failed or retreated. I went with the khan against the Zamogedi when only nine returned. I fought as his rear guard, protecting him from the Zamogedi. I took the khan to the ordu of my family and sheltered him. I strengthened the khan when he returned to the Zamogedi to take his revenge. Together we beat them—killing their men and enslaving their women and children.

"All this because I was his anda. When the Khassidi surrendered to me, offering gifts of gold and silk, weren't those gifts sent to the khahan? 'These things that are given are the khahan's to give.' Isn't that the law?" Chanar faced the other khans at the fire, directing his questions to them, not Yamun or the priest.

"Is true, Great Prince," mumbled Goyuk to Yamun, his toothless speech made worse by drink. "He sent it all to you."

Satisfied with Goyuk's answer, the general turned to face the lama.

"But now," Chanar growled, narrowing his eyes at Koja, "the valiant man no longer has gifts to send and another sits at his anda's right hand. And that's how the story ends." The general turned from the priest, stalked back to his stool, and sprawled there, satisfied that his point had been made.

With a sharp hiss, Yamun stood and took a step toward Chanar, who watched him like a cat. The khahan's fists were clenched tightly, and his body swayed with tension.

"This is no good," Goyuk said softly, laying his hand on Yamun's arm. "Chanar is your guest."

Yamun stopped, listening to the truth in Goyuk's words. Koja quietly slid his stool away from the khahan, fearful of what might happen next. The singing from the other fires started up again.

"Nightguards!" snarled Yamun. "Come with me. I'm going to visit the other fires." With that he wheeled and strode off into the darkness. The guards streamed past, and the quiverbearers followed after, carrying food and drink for the khahan no matter where he stopped.

Those around the fire watched the entourage wend down the hillside. Koja sat quietly, suddenly feeling himself among enemies.

"This is a dangerous game you play, Prince Chanar," observed Goyuk, leaning over to speak softly in Chanar's ear.

"He can't kill me," Chanar confidently replied as he watched Yamun march down the hill. "The Khassidi and many others would go back to their ordus if he did."

"Is true, you are well loved, but Yamun is the khahan," the old man cautioned.

Chanar dismissed Goyuk's comments with a gulp of kumiss. As he drank down the cup, he once again saw Koja on the other side of the fire.

"Priest!" he hissed at the lama. "Yamun trusts you. Well, I am his anda! You are a foreigner, an outsider." The general leaned forward until his face was almost in the flames. "And if you betray the Tuigan, I'll have great fun hunting you down. Do you know how a traitor is killed? We crush the breath out of him under a plank piled with heavy stones. It's a slow and painful death."

Koja paled.

"Remember it and remember me," Chanar warned. With those words, he threw the rest of the kumiss on the fire and stood. "I must go to my men," he told Goyuk Khan, ignoring Koja's presence. The old khan nodded, and Chanar walked off into the darkness.

The rest of the evening seemed to pass quickly and slowly all at once. At first Koja was content to sit near the fire, keeping away the increasing chill of the frosty night air. The servants kept refilling his golden goblet, having long since taken the skull away. The old khan, Goyuk, seeing that the priest wasn't going anywhere, began to talk incessantly. Koja only understood about half of what the codger said, but smiled and nodded politely nonetheless. The khan talked about his ordu, his horses, the great battles he had fought in, and how a horse had kicked out his teeth. At least, that is what Koja thought he was discussing. As the night went on, Goyuk's speech became increasingly unintelligible.

Several times, Koja tried to get up and leave. Each effort brought a storm of protest from Goyuk. "This story is just getting good," he would insist and then demand more wine for the priest. Eventually, Koja wasn't even sure his legs would work if he did manage to get away.

At last, the kumiss and wine had their effect. The old man nodded off in midsentence, then snapped back awake and rambled on for a while longer. Finally, Goyuk bedded down, moving the stool out of the way and wrapping the rug around himself. Koja, too tired to walk back to his yurt, followed custom, rolling the thick felt rug tightly around himself. Within a few minutes he was sound asleep.

Down the slope, a hooded servant slipped among the fires, seeking out one man. At each circle he stopped, standing in the shadows, staring at the faces. Finally, at one fire, where the drinking was the most riotous, the servant found the man whom he sought. Moving through the darkness, he sidled up closer to his goal. The revelers were too involved with their drink to notice him. Softly, he leaned up and whispered in the ear of his man.

"The khadun, Lady Bayalun, hears that you have been wronged this night," he hissed. '"Is Chanar to let himself be usurped by a stranger?' she asks."

"Eh? What do you say?" the drunken General Chanar blurted in surprise.

"Shhh. Quietly! She fears you fall from Yamun's favor—"

Chanar moved to speak, but the messenger quickly pressed his hand on the general's shoulder. "This is not the place to talk. The khadun opens her tent to you, if you will come."

"Hmm... when?" Chanar asked, trying to look at the man without turning his head.

"Tonight, while the eyes of others are occupied." The messenger waited, letting Chanar make his decision.

"Tell her I'll come," Chanar finally whispered. Without another word, the messenger faded back into the darkness.

The campfires had burned down to lifeless ashes, and only thick plumes of smoke rose up into the blackness of night. Koja found himself sitting up, shivering in the cold, rugs and robes fallen off his back. It didn't strike him as odd that he could see the sleeping forms of men, the empty yurts flapping in the breeze, even in perfect darkness. They were just grayer forms against the black plain.

There was a clink of rock against rock behind him and then a soft wet scrape of mud on stone. Wheeling around, he was confronted by a man in yellow and orange robes, hunched over so his face could not be seen. The man's hands were doing something, something that matched the sounds of stone against stone.

"Who—," Koja started to blurt out.

The man looked up and stopped Koja in midsentence. It was his old master from the temple, his bald head lined with age. The master smiled and nodded to the priest and then went back to his work, building a wall. With a scrape, the master dragged a trowel across the stone's top, spreading a thick layer of mortar.

Koja slowly turned around. The men, fires, and yurts were gone. A low wall encircled him, trapping him beside the campfire. Turning back, Koja watched his master lift a square block and set it in place atop the fresh mortar.

"Master, what are you doing!" Koja could feel a growing panic inside himself.

"All our lives we struggle to be free of walls," intoned the master, never once stopping his work. "All our lives we build stronger walls." With a scrape and heavy thud, another stone was set in place. "Know, young student, of the walls you build—and who they belong to."

Suddenly the wall was finished, towering over Koja. The master was gone. Koja heaved to his feet and whirled about, looking for his mentor. There, in front of him, was a banner set in the ground. From its top hung nine black horsetails—the khahan's banner. He turned the other way. There was another, with nine white yak tails—the khadun's banner. Stumbling backward, he tripped and fell against another—a golden disk hung with silken streamers of yellow and red-Prince Ogandi's banner. Panicked, Koja fell to the ground and closed his eyes.

A sound of heavy breathing, and a blast of steam across Koja's face forced him to look again. The banners were gone, and the wall that circled him shivered and moved. It became a great beast, black and shimmering. A pair of eyes, inhuman and cold, stared down at him.

"Are you the khahan of the barbarians?" the beast boomed.

"No," answered Koja in a weak whisper.

The eyes blinked. "Ah. Then you are with him," it decided. "That is good. Finally, it is time." The eyes glowed brighter. Fearful, Koja looked away from the baleful gleam. There was a rushing of wind and then the shape was gone.

Looking up, the priest saw his master again. "Be careful, Koja, of the walls you build," the old lama called out. The master faded, growing dimmer to Koja's sight, until there was nothing but the dull gray horizon. Then there was nothing at all.

The priest woke slowly, dimly remembering the voices from his sleep. A sharp tang welled up at the base of his skull, tingling the stubble of his neck hair. Involuntarily, the thin priest inhaled deeply. Suddenly, he was wide awake, sneezing and gagging, his nostrils filled with the smoke of burning manure. He flailed about, then opened his eyes. Thick wads of stinging smoke assailed him. Koja crawled out of his rug and into clear air.

"It is a good day," a wavering voice somewhere to Koja's left said.

Still blinking, the priest looked toward the voice. He could hardly see the speaker because the dawn sun blazed behind the man's shoulder. Koja shielded his eyes from the orange-red glow with one hand and rubbed away the last of his tears with the other. Sitting next to the thickly smoking campfire was the ancient Goyuk Khan, poking at the coals with a stick. He looked back at Koja and smiled one of his broad, toothless grins.

Koja weakly smiled back. His head felt thick from drink and pained from his sudden awakening. His mouth was gummy. The years among the lamas had not prepared him for a night of feasting with the Tuigan.

"Is time to eat," Goyuk said. He didn't look the least bit haggard from the celebration. Poking the fire again, Goyuk fished out an ash-covered lump, bits of burning coals still clinging to it. Picking it up carefully, he brushed the embers away with his dirty fingers and held it out to Koja.

Koja looked at it dubiously, knowing full well that he had to take it or offend the old khan. It looked like a scrap of the horsemeat sausage, roasted in the fire. He gingerly took it, juggling it between his hands to avoid burning his fingers.

"Eat," urged the khan, "is good."

"Thank you," said Koja with a forced smile. He ate it down quickly, doing his best not to taste the meat. Breakfast finished, Koja struggled to his feet to look for water. The sun had barely risen over the horizon, but already men were about. The guards were changing, the dayguards replacing the nightguards. Quiverbearers and household slaves were going from yurt to yurt, preparing for the morning.

Not everyone was awake, however. Koja weaved through the sleepers clustered around the feast-fires. Most of the revelers were still snoring blissfully, unusual for the Tuigan camp, which was normally bustling by this hour. Some were wrapped in their blankets and rugs, curled closely around small mounds of smoldering embers. However, more than a few were sprawled haphazardly over the ground, their kalats pulled up tight around them. Koja guessed many of them slept on the same spots where they had passed out the night before.

After much futile searching, Koja finally collared a servant carrying a bucket of water. Scooping it up with his hands, he gulped down a mouthful. Though cold enough to numb his fingers, the priest splashed the water over his face and head, vigorously rubbing his skin to clear his brain.

One of Yamun's quiverbearers presented himself to Koja. "The Illustrious Emperor of the Tuigan, Yamun Khahan, sends me to ask why his historian is not in attendance at the yurt of his lord." The servant remained kneeling before the lama.

Koja looked at the man in surprise. He hadn't expected the khahan to conduct business so early this morning. Furthermore, the priest didn't realize his presence would be needed so constantly. "Take me to his yurt," he ordered.

Obediently, the servant led Koja through the clutter around the feast-fires. Reaching the tent, the man announced Koja's arrival. The priest was quickly ushered inside.

This morning the yurt was arranged differently. Yamun's throne was gone, and the braziers had been moved to the sides of the tent. The flap covering the smoke hole was opened wide, as was the door, allowing rays of sunlight to dazzle the normally gloomy interior. In the center of the yurt, in a shaft of sunlight, sat a circle of men. Yamun was bareheaded, his conical hat set aside. The light gleamed off his tonsure and brought out the red color of his hair. He still wore the heavy sable coat he had worm the night before, though now it was mud-stained and smudged with soot. The other men had likewise removed their hats, making a ring of shining bald domes in the center of the yurt. Koja was reminded of the masters of his temple, although they didn't sport the long side braids favored by these warriors.

"Historian, you'll sit here," called out Yamun as the lama entered. He slapped his hand on the rug just behind himself.

Koja walked around the circle and took his seat. Chanar, bleary-eyed from the night's festivities, sat on one side of Yamun. Goyuk sat on the other. There were three others wearing golden cloths and embroidered silks, signs that they were powerful khans, but Koja did not recognize them. Their rich clothes were travel-stained and rumpled. At the farthest end of the circle, sitting slightly away from the rest, was a common trooper. His clothes, a simple blue kalat and brown trousers, were filthy with mud and grime. He stank powerfully, Koja noticed as he walked by.

The khans glanced toward Koja as he sat. Goyuk smiled another of his gaping smiles. A look of displeasure sparked in Chanar's eyes. Yamun leaned forward, drawing their attention to the sheet spread out in front of them.

It was a crude map, something which surprised Koja. He hadn't seen any maps since arriving, and he had assumed the Tuigan had no knowledge of cartography. Here was another surprise about his hosts. The lama craned his neck, trying to get a view of the sheet.

"Semphar is here," Yamun said, continuing a conversation begun before the priest entered. He thrust a stubby finger at one corner of the sheet. "Hubadai waits with his army at foot of Fergana Pass." He traced his finger across the map to a point closer to the center. "We're here."

"And where is Jad?" asked one of the khans Koja didn't know.

"At the Orkhon Oasis—there." Yamun pointed to the far side of the map.

The priest strained even harder to see where Yamun was indicating. All he could make out was a blurry area of lines and scribbles.

"And Tomke?" the same khan asked. He was a wolf-faced man with high, sharp cheekbones, a narrow nose, and pointed chin. His graying hair was well greased and bound in three braids, one on each side of his head and a third at the back.

"He stays in the north to gather his men. I'm going to hold him in reserve," Yamun explained. There was a grunt of general understanding from the men listening. They studied the map for a few minutes, learning the dispositions of the armies.